|

|

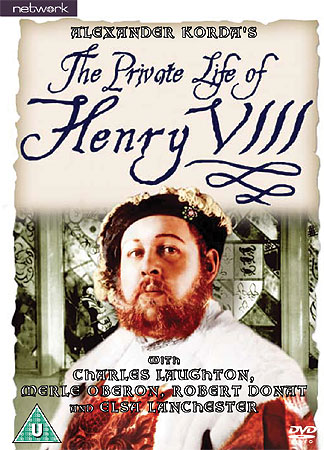

Private Life of Henry VIII (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th April 2009). |

|

The Film

One of the first British ‘talkies’ to achieve widespread commercial success in America (making approximately $500,000 oin the US), The Private Life of Henry VIII (Alexander Korda, 1933) earned Charles Laughton an Academy Award for his performance as the complex and controversial monarch (see Balio, 1976: 134). However, the film eschews almost all mention of the social and political issues surrounding Henry VIII’s reign, instead focusing on a witty examination of the king’s many marriages. In this way, the film could be cited as one of the earliest examples of the modern ‘costume drama’. The Hungarian émigré Alexander Korda ‘was a confirmed Anglophile’ who sought to celebrate and promote English culture, via his ‘own epics of English nationhood, The Private Life of Henry VIII and Fire Over England’ and, later, his ‘trilogy of imperial dramas, Sanders of the River, The Four Feathers and The Drum’ (Richards, 1997: 186, 33). Through his films, Korda sought to promote ‘the most noble traits in the English character and spirit’ (ibid.: 33). According to legend, Korda’s decision to make The Private Life of Henry VIII was apparently inspired by a ride with a cab driver who sang the music-hall song ‘I’m ‘Enery the Eight, I Am’, about a man who is the ‘eighth old man’ of a widow who’s ‘been married seven times before’; Korda misinterpreted the song, believing it to be about the king (Slide, 1985: 10).

Casting Laughton as the king, due to the great actor’s remarkable resemblance to the image of Henry VIII as captured in Hans Holbein’s portraits of the monarch, Korda designed The Private Life of Henry VIII ‘not [as] a realistic realistic historical study but [as] a string of episodes in the marriage saga of Henry VIII as he is popularly imagined’ (Low et al, 2005: 167). The filmmakers had little concern with historical verisimilitude: ‘although a historical adviser was employed, modern colloquial language and anachronistic hair styles were cheerfully allowed’ (Low et al, 2005: 167). In the hands of Korda and Laughton, Henry VIII is depicted as a lustful and bawdy figure. The opening portion of the film juxtaposes the execution of Anne Boleyn (Merle Oberon) with the preparations for the king’s marriage to Jane Seymour (Wendy Barrie). (The film omits Henry’s marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, dismissing her with a title card which ironically states that she was ‘of no particular interest. She was a respectable woman’.) Henry is presented as a man who is desired by the people around him: as the maids arrive to tidy Henry’s chambers, they express desire for the man, claiming to ‘wonder what he looks like in bed’. However, there is a recognition that marriage to the king is not necessarily something that should be aspired towards: when one of the maids notes that ‘Anne Boleyn died this morning; Jane Seymour takes her place. What luck!’, her colleague ironically states ‘For which of them, I wonder’. Later, in an example of the film’s frequently black humour, one of the maids notes that Boleyn ‘died so that the king may marry Jane Seymour’, and another maid notes that ‘that’s what they mean when they say “Chop and change”’. During the first half of the film, both Henry and English society are depicted as somewhat callous through the flippant way with which Boleyn’s execution is regarded: whilst Boleyn waits to be executed, Henry makes preparations to marry Seymour and flirts with Katherine Howard (Binnie Barnes), who later in the film will become his fifth wife; meanwhile, the crowds revel in Boleyn’s execution and the executioners whistle happily as they sharpen the sword that will be used to execute the former queen. In the aftermath of Boleyn’s execution, a woman in the crowd insensitively notes ‘And that frock. Wasn’t it… too divine?’ Korda gives Boleyn some power at her execution by filming her in a very extreme low-angle shot as she ambivalently asserts ‘A lovely day’; as if to underscore the trivial and offhand way with which Boleyn’s execution is regarded by her contemporaries, Korda then cuts brutally to Seymour wandering into a room and flippantly declaring ‘What a lovely day’.

In these early sequences, Korda wittily dissects both Henry VIII and Tudor society; if not quite villainous, Henry is depicted as a character with whom it is difficult to sympathise. Aside from the juxtaposition of Boleyn’s execution with Henry’s preparations to marry Seymour (and his dalliance with Katherine Howard), Korda foregrounds the king’s misogyny: at one point, Henry advises that ‘If you want to be happy, marry a girl like my sweet little Jane: marry a stupid woman’. However, as the film progresses Henry becomes progressively more sympathetic. In his relationships with his wives, he is increasingly henpecked. He is outwitted and outmanoeuvred by Anne of Cleves (played by Laughton’s wife Elsa Lanchester), and at the end of the picture he is reduced to sneakily eating chicken legs behind the back of his last wife, Katherine Parr (Everley Gregg). Often seen as validating the notion of consensus politics, The Private Life of Henry VIII is often argued to contain ‘a representation of a benevolent king whose subjects understand and support it’ (Street, 2000: 57). Sarah Street argues that the film shows a ‘cross-class bond that paradoxically confers on the lower echelons in the film a “superior” status that is characterised by an apparent insight into the king’s personal shortcomings and human frailties, particularly as far as women are concerned’ (ibid.: 58). This insight into the king’s weaknesses is offered through scenes in which Henry’s servants comically discuss his affairs. The film depicts ‘Henry’s royal status’ as a ‘burden’, and ‘[f]ar from being represented as a “divine being”, Henry is weak and pathetic, longing for the personal freedoms enjoyed by his subjects. The demands of the state are depicted as crushing his spirits’ (ibid.). In awareness of this, at the birth of his son, he tells the child ‘You smile, do you? Well, smile now you may. You’ll find the throne of England no smiling matter’. Later, Thomas Culpeper (Robert Donat) tells Katherine Howard (with whom he is having an affair), ‘If you’ve got your crown, what would it be worth without love?’ Culpeper’s advice is equally applicable to the king himself, who towards the end of the film reflects that ‘Love is drunkenness when one is young; love is wisdom at my age’.

Writing in The Observer at the time of the film’s release, C. A. Lejeune stated that the film ‘is national to the backbone… It is the British prestige picture that we have been demanding for ten years back, not pedantic, not jingoistic, but as broadly and staunchly English as a baron of beef and a tankard of the best homebrew’ (quoted in Chapman, 2005: 21). In an early sequence, Henry characteristically identifies the positive aspects of English culture, noting that ‘I’m an Englishman. I can’t tell you one thing and mean another’. Lejeune also said that the film ‘combines a kind of forthright and blundering honesty with a childish naivety of humour’ (ibid.). This humour was a little too risqué for some. At one point, discussing the King’s marriages the servants observe that ‘He tries too hard, if you ask me… to say nothing of the side dishes. A little bit of this, a little bit of that. What a man wants is regular meals’. To this, another servant suggests ‘Yes, but not the same joint every night. A man loses his appetite after four courses’.

When the film was released to American cinemas in 1935, some of the more risqué dialogue was removed in order to comply with the more censorious nature of US cinema at the time (see Street, op cit.: 59). Prior to production, upon reading the script the BBFC’s deputy chief censor J. C. Hanna suggested that ‘The language throughout may be true to the standards of the day, but it is far too outspoken and coarse for the present day’ (quoted in Chapman, op cit.: 30). In light of this, the censors advised that ‘all suggestions that [Henry’s] marriage [to Anne of Cleves] is being consummated’ should be deleted (quoted in ibid.). The sequence in question involves Henry, on his wedding night, trying to explain sexual intercourse to the faux-naïve Anne of Cleves; but, most likely in concession to the BBFC’s demands, instead of consummating their marriage the two end up playing cards. The scene descends into bedroom farce: Henry loses so much money to his wife that he is forced to order his courtiers to gather together some more cash, and at the end of the sequence Henry is outwitted by his wife, offering her a divorce that benefits her greatly.

Despite its considerable reputation, The Private Life of Henry VIII has been criticised for its lack of engagement with the social fallout of Henry’s reign. In 1937, F. D. Klingender criticised the film’s lack of engagement with the social and historical conditions relating to Henry VIII’s reign: ‘Henry VIII, perhaps more than any other monarch in English history, broke down the bulwarks of a whole epoch and paved the way for a new form of society. He created a new ruling class and established a national church. Yet, from his “life” all his public actions without exception are eliminated and the attention of the audience is directed exclusively to his private love affairs’ (quoted in Chapman, op cit.: 29). The film certainly sidesteps the big issue of the Reformation, and it is true that ‘[t]hroughout the film, the private and the personal intrude upon the public and the political’: any discussion of politics is ‘cut short by the intrusion of his current amour’ (ibid.: 31). However, the film does engage obliquely with social issues of the time of its production. Produced at a time of high unemployment, the banter between the French executioner (who has been employed to execute Boleyn) and his English counterpart would have spoken to the employment-related anxieties of many audience members: ‘What’s wrong with English steel? And what’s wrong with an English headsman? I was good enough to knock off the queen’s five lovers, wasn’t I? Then why do they want you over, a Frenchman from Calais? […] There are enough English executioners out of work as it is’. Later, Henry reflects on the topic of war and the internal conflicts within Europe that were already evident during the early 1930s and would gain increasing relevance as the decade progressed: ‘What’s the use of wars, wars, wars again. If those French and Germans don’t stop warring, the whole of Europe will be in ruin. I want to compel them to keep peace, and there’s no-one in Europe to help me’. Like many other independent British films, The Private Life of Henry VIII has also been criticised for being ‘stagy’ and ‘uncinematic’ in comparison with similar Hollywood pictures. However, for Andrew Higson, ‘as for other advocates of a British, or English, “heritage” cinema, aspects of form such as frontal staging, long takes and a predominantly stationary camera are all intended to enhance a film’s pictorial qualities’ (Higson, cited in Chapman, op cit.: 25). Therefore, as Andrew Higson notes, ‘to accuse films of being primitive, or uncinematic, or too literary, or too theatrical, as many critics have done over the years’ is to ignore the means by which British cinema has sought to differentiate itself ‘from the products of classical Hollywood cinema’: ‘Uncinematic may simply mean not like classical Hollywood cinema’ (Higson, quoted in ibid.).

Video

The Private Life of Henry VIII is presented in its original screen ratio of 4:3. The image is perfectly acceptable: it is detailed and clear. The print suffers from some wear and tear, but this is to be expected for a film of this vintage.

Audio

Audio is presented via a dual mono track. This is clear and audible, with some minor damage present from time to time. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole extra is an image gallery.

Overall

A fast-paced and witty film, The Private Life of Henry VIII benefits greatly from Laughton’s performance as the king. Criticisms that the film largely sidesteps any attempt to engage with the social fallout from Henry’s reign are valid, although the film’s strengths and focus lie elsewhere. A true classic of early British sound cinema, this DVD release of The Private Life of Henry VIII is to be commended, as the film has been unavailable on DVD in Britain till now. However, a film of this importance could benefit from a greater array of contextual material. References: Balio, Tino, 1976: United Artists: The Company Built by the Stars. University of Wisconsin Press Chapman, James, 2005: Past and Present: National Identity and the British Historical Film. London: I. B. Tauris Low, Rachael et al, 2005: History of British Film, Volume VII – The History of the British Film 1929-1939: Filmmaking in 1930s Britain. London: Routledge Richards, Jeffrey, 1997: Films and British National Identity: From Dickens to ‘Dad’s Army’. Manchester University Press Rosenstone, Robert A., 1995: Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to Our Idea of History. Harvard University Press Slide, Anthony, 1985: Fifty Classic British Films, 1932-1983: A Pictorial History. Courier Dove Publications Street, Sarah, 2000: ‘Stepping Westward: The distribution of British feature films in America, and the case of The Private Life of Henry VIII’. In: Ashby, Justine & Higson, Andrew, 2000: British Cinema: Past and Present. London: Routledge: 51-61 Walker, Greg, 2003: The Private Life of Henry VIII. London: I. B. Tauris For more information, please visit the homepage of .

|

|||||

|