|

|

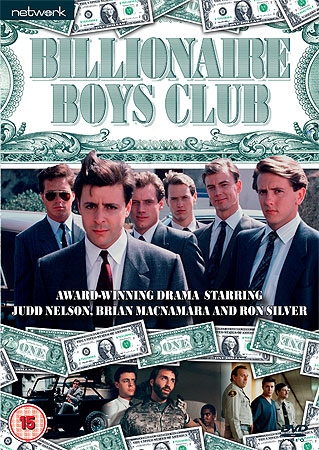

Billionaire Boys' Club (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd August 2009). |

|

The Show

Billionaire Boys’ Club (Marvin J. Chomsky, 1987)

Made in 1987, this two-part NBC mini-series was based on the then-topical case of the so-called Billionaire Boys’ Club (BBC). Created by Joe Hunt, the Los Angeles-based Billionaire Boys’ Club was devised in 1983 as a ‘get rich quick’ investment pool for Hunt and several of his former school friends. However, when a conman named Ron Levin swindled the Billionaire Boys’ Club out of around four million dollars, Hunt plotted Levin’s murder. Following their murder of Levin, the Billionaire Boys’ Club arranged the kidnapping of the father of one of the BBC’s members, Hedayat Eslaminia. The BBC planned to torture Eslaminia into revealing the whereabouts of thirty million dollars that Eslaminia falsely claimed to possess. However, Eslaminia died when the kidnappers plugged the airholes in the trunk they used to transport him from his apartment to their base of operations. Unusually, this two-part dramatisation of the case of Hunt and the Billionaire Boys’ Club was broadcast on American television before the real-life trial had reached its conclusion; the mini-series was also broadcast three years before the publication of the book on which it was based, Sue Horton’s non-fiction account of Hunt’s crimes, The Billionaire Boys’ Club (1990). Like the case of the upper middle-class Menendez brothers, who in 1989 killed their parents in order to get their hands on their parents’ estate, the case of Joe Hunt and the BBC has come to represent the dark side of 1980s corporate culture and its ‘greed is good’ ethos. (Ironically, during the trial of the Menendez brothers this very dramatisation of the case of the Billionaire Boys’ Club was cited as a contributing factor to the brothers’ decision to murder their parents; see Abrahamson, 1993: np).

The film features Judd Nelson as Joe Hunt. At this point in his career, thanks to his roles in such ‘coming of age’ films as The Breakfast Club (John Hughes, 1985) and St. Elmo’s Fire (Joel Schumacher, 1985), Nelson was one of the most recognisable faces of the 1980s ‘Brat Pack’, along with Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, Andrew McCarthy, Charlie Sheen and Robert Downey, Jr. Consequently, for many viewers Nelson embodied American youth culture of the 1980s, which makes his casting here as Joe Hunt – who represents the dark side of the 1980s culture of excess – highly effective. As played by Judd, Hunt is a man for whom ‘evil is good if you want it bad enough; lying is peachy-keen if it gives you an edge’ (Leonard, 1987: 117). Hunt persuades his associates to become accomplices in murder through his philosophy of ‘paradox thinking’, a half-baked appropriation of the ideas of moral relativists like Darwin and Nietzsche. Hunt tells his associates that ‘It all depends how you look at things. There are no absolutes: there’s no black and no white, just shades. Depending on how you look at it, black is white and white is black. It’s a paradox; that’s what I call paradox-thinking’. However, Hunt’s paradox-thinking is peppered with soundbites that establish a relationship between Hunt’s particular form of psychopathy and the corporate sensibility of the 1980s: after watching First Blood in a cinema, Hunt informs his associates that ‘In our world, winning is everything [….] Business is war, like war is a business’. Likewise, immediately prior to staging Ron Levin’s murder Hunt asserts, ‘Let’s execute this merger’. This television dramatisation of the Hunt case suggests that there is something immeasurably unhealthy about the culture of materialistic excess that characterised the 1980s, and draws parallels between Hunt’s psychopathic behaviour and 1980s corporate culture. The members of the BBC clearly see themselves as members of an elite who deserve better than other people: recruiting the members of the BBC in a nightclub, Hunt appeals to their egos by telling them that they are ‘not like anyone else: you’re affluent, ambitious, well-educated, from a wealthy family. And you don’t want to wade through a lot of corporate garbage to get to the top, right?’ To his associates, Hunt describes the BBC as ‘our corporation’ and suggests that the BBC ‘is looking for guys like you, who want to start at the top and have investment capital: we bypass corporate political gains’.

The drama begins in a courtroom; the creation of the Billionaire Boys’ Club and the crimes perpetrated by its members are told in flashback. Parallel editing is deployed to establish a relationship between the versions of events told in the courtroom and the BBC’s exploits.

Billionaire Boys’ Club takes place in the kind of milieu that, during the same period, Bret Easton Ellis was using as the basis for novels such as Less Than Zero (1985), The Rules of Attraction (1987) and American Psycho (1991). As in Ellis’ novels, in Billionaire Boys’ Club wealthy and educated ‘preppy’ types exhibit a dehumanisation caused by their immersion in a world of materialistic excess. Rewatching this drama, it’s possible to infer that Mary Harron used it as a point of reference when making her 2000 adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho: both films inhabit the same environment of nightclubs and boardrooms, focusing on troubled 1980s yuppie types. With Hunt’s relativist ‘paradox thinking’ at its centre, Billionaire Boys’ Club may also be a precursor to Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club (1996): as Hunt tells the other members of the BBC, ‘I’m going to suggest two rules: the first, never be sorry for anything that you do [….] The second rule is, it’s okay to lie as long as you know the truth and it’s good for the BBC’.

This DVD presents Billionaire Boys’ Club in two parts, with the first part running for 90:39 mins (PAL) and the second part running for 89:28 mins (PAL). To the best of this reviewers’ knowledge, Billionaire Boys’ Club has previously only been released on home video in a version edited to feature length; this DVD release therefore marks the first time that the complete two-part television film has been released on home video.

Video

Billionaire Boys’ Club is presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. Shot on film, the mini-series has an expensive aesthetic; the transfer contained on this DVD is very handsome. Colours are natural and life-like, and the image is crisp and detailed.

Audio

Billionaire Boys’ Club is presented via a two-channel stereo track. Once again, this is absolutely clear. There are no subtitles.

Extras

There is no contextual material.

Overall

A fascinating drama, Billionaire Boys’ Club is an interesting examination of the dark side of the materialistic culture of the 1980s. Concerns about the dehumanising corporate culture of excess are still with us, if the popularity of millennial fictions such as Fight Club and The Matrix (Andy & Larry Wachowski, 1999) are to be trusted. As a consequence, this television dramatisation of the Hunt case is possibly as pertinent now as it was in 1987, offering a very different representation of American society as that contained in most 1980s Hollywood cinema – especially the films associated with Nelson’s other ‘Brat Pack’ associates. Nelson is very good as Hunt, and the drama has an intriguing non-linear structure. This DVD comes with a very strong recommendation. References: Abrahamson, Alan, 1993: ‘Movie called factor in Menendez killings - Trial: TV film on Billionaire Boys Club inspired brothers to kill parents, prosecutors say outside juries' presence. Brothers' defense lawyers to begin their case next week’. The Los Angeles Times (14 August, 1993). [Online.] http://articles.latimes.com/1993-08-14/local/me-23846_1_billionaire-boys-club (Accessed 3 August, 2009) Leonard, John, 1987: ‘Boys Will Be Boys’. New York Magazine (9 November, 1987): 117 For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|