|

|

Armchair Theatre (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th January 2010). |

|

The Show

First appearing in 1956, a year after ITV began broadcasting, the single-play strand Armchair Theatre (ABC, 1956-68; Thames, 1970-74) is often considered as an integral part of the ‘golden age’ of British television drama (Tise Vahimagi, cited in Thumin, 2004: 134). It has been suggested that the series was developed by ITV as an attempt to win a certain amount of cultural prestige following the channel’s emphasis, in its first year, on populist shows such as Sunday Night at the London Palladium (ABC, 1955-67) (see Duguid, 2003: np). In fact, in its early years Armchair Theatre’s popularity was facilitated by its scheduling immediately after Sunday Night at the London Palladium. Influenced by the growth of social realism in literature, theatre and film during the late 1950s and 1960s (a movement pioneered by John Osborne’s 1956 play Look Back in Anger) Armchair Theatre quickly gained a reputation as a series that was dominated by ‘kitchen sink’ dramas – although in actuality, the series also occasionally featured narratives from other genres, including science fiction. The move into the realm of social realism took place when Canadian producer Sydney Newman took over production of the series in 1958; Newman, who in most critical discourse is seen as the overriding ‘author’ of Armchair Theatre’s approach to drama, was committed to producing socially-relevant plays by new writers and once stated that ‘I came to Britain at a crucial time in 1958, when the seeds of Look Back in Anger were beginning to flower. I am proud that I played some part in the recognition that the working man was a fit subject for drama, and not just a comic foil in middle-class manners’ (Newman, quoted in Sydney-Smith, 2002: 158; also see Sinfield, 1983: 160). (Following his move to the BBC in 1963, Newman would eventually be responsible for the development of the BBC’s similar anthology series The Wednesday Play, 1964-70.) Eventually, Armchair Theatre’s reputation as an outlet for downbeat and gritty domestic dramas led to the series being parodied as ‘Armpit Theatre’ on the BBC radio comedy Round the Horne. ABC’s production of Armchair Theatre continued until 1968, when the shakeup of the ITV franchises took place. In 1970, Thames took over production of the series. However, by this stage the studio-bound Armchair Theatre was seen as a regressive series that harkened back to an era when television looked to theatre for its inspiration; by the late-1960s, single-play strands in general were struggling to attract audiences (Thumin, op cit.: 132). Armchair Theatre was abandoned in 1974, and effectively replaced with Armchair Cinema (Thames/Euston Films, 1974-5). Produced by Thames Television’s subsidiary Euston Films, which was established with the idea of making ‘films for television’ (ie, shot on film rather than videotape and making use of real locations rather than studio sets), Armchair Cinema would look away from theatre towards cinema for its inspiration – as signified in the change of title. Unlike Armchair Theatre, Armchair Cinema moved away from ‘stagey’ studio-bound dramas and featured a heavy emphasis on location shooting. Armchair Cinema also differentiated itself from Armchair Theatre through being shot wholly on 35mm film: television was pushing ‘away from the production of studio-based plays towards location-based, filmed drama’ (Cooke, 2007: 123). The episodes in this DVD set are all taken from the Thames era of Armchair Theatre’s production and were produced between 1970 and 1973, effectively marking the last gasp of the theatre-influenced single-play strand. Please also see our review of Armchair Cinema. Disc One: ‘Say Goodnight to Your Grandma’ (53:07) ‘Office Party’ (50:31) ‘Brown Skin Gal, Stay Home and Mind Bay-Bee’ (52:57) ‘Detective Waiting’ (52:58) Disc Two: ‘Will Amelia Quint Continue Writing “A Gnome Called Shorthouse”?’ (53:23) ‘The Folk Singer’ (51:20) ‘A Bit of a Lift’ (52:24) ‘Red Riding Hood’ (52:10) Episodes: ‘Say Goodnight to Your Grandma’ (53:07)

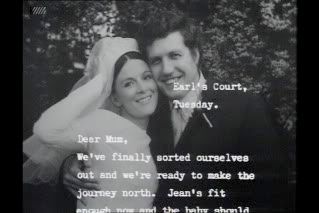

Written by Colin Welland and starring Welland and Susan Jameson, both veterans of the social realist police series Z Cars (BBC, 1962-78), ‘Say Goodnight to Your Grandma’ opens with a letter in which Tony (Welland) declares that he, his wife Jean (Jameson) and their new baby daughter Cressida will travel from their home in London to the north of England to see Tony and Jean's mothers – during the journey, Tony and Jean refer to the event as 'the meeting of the matriarchs'.

The visit will mark the first time that Tony's mother (Madge Ryan) has met Cressida, her first grandchild. Tony's mother, a widow, has no other children; by contrast, Jean's parents have four other grandchildren, and Tony and Jean seek to hide from Jean's mother (Mona Bruce), a Catholic, that Cressida will not be christened. At Tony's mother's house, Tony's mother expresses shock when Jean reveals that Tony was present when she gave birth to Cressida, asking Jean 'Was he there? All the time?' before declaring to Tony that 'I wouldn't have liked your father to have seen that'. Later, Tony's mother seemingly accidentally mentions Tony's christening to Jean's mother, but in the kitchen Jean suggests that Tony's mother may have raised the topic deliberately. Jean tells Tony that 'she's [his mother is] a bitch'. Storming out of the room, Jean aggressively warns Tony that 'You're a fool. You're a bloody big, fat fool'; later, Jean asserts to her mother that she is 'not committing my daughter to a load of superstitious nonsense'. Whilst Tony's mother encourages Tony to revisit old photographs of his youth, including pictures of his former sweethearts – one of whom causes Tony's mother to reflect, 'She was a lovely girl' – Jean ponders in voiceover, 'What makes her do it, I wonder? Enjoy the raising of ghosts, the tearing open of old wounds? [….] It's a bit frightening, almost psychopathic. She's like a terrible, destructive ogre. Perhaps it's deep in their blood'. By contrast, in voiceover Tony reflects that it was 'Jean's idea we got away from here, moved. Too stifling, she said'. They moved to London, where Tony found he had 'No mates, a howling kid and lousy ale. Aye, me mother's right: these were the bloody days'. By reflecting on his past, Tony's mother inspires in Tony a sense of resentment towards Jean, for taking away from his home to London, where he is clearly unhappy. Tony's mother's antics seem designed to cause a rift between Tony and Jean, and Jean warns Tony that his mother has a 'stupid plan' to prise them apart. When Tony's childhood friend Ken telephones Tony's mother's house, Tony agrees to meet him at the local club. This causes an argument with Jean, who asks Tony 'when are you going to grow up? A couple of flicks through some tatty old snaps, and you’re back in rompers again, clutching at your mother’s skirts. Your daughter and I might just as well not exist’.

It is clear that Jean’s Oedipal nightmare is coming true when Tony calls his mother and asks if he can bring his friends back to his mother’s house; Tony’s mother tells Tony that this is absolutely fine before complaining about it to Jean. However, Jean devises a plan, and when Tony brings his friends back to his mother's house, a provocatively-dressed Jean begins to dance with them. The men display sexual envy, and Tony becomes increasingly agitated. In the kitchen, Tony's mother tells him that ‘She’s making you look a fool, a pansy – you know that? Throwing herself at those lads, embarrassing them. And you let her; you just sit there and let her. Listen to her: they must think she’s a right common little piece’. Tony's mother threatens to go into the room and stop Jean, who is using her sexual guile to taunt Tony's friend Ray (Jack Smethurst), but Tony prevents her from doing so. ‘It’s her game. Let’s see if she can finish it’, Tony asserts to his mother. Jean's antics cause Tony to reflect on the childish immaturity of his behaviour; he argues with his mother, telling her that ‘They’re all grown men now [….] We’re all thirty and over. What the hell are we doing here?’

Jean is about to strip for Tony’s friends before she is stopped by Tony’s mother. Tony stands in the sidelines, watching from the shadows; Jean looks at him meaningfully, ashamed that he wasn’t the one to stop her. Meanwhile, the baby cries from upstairs. In the next shot, Jean is nursing the baby and the men are cooing over her. Well-observed and with several experimental elements (including an almost avant-garde use of voiceovers from multiple perspectives), ‘Say Goodnight to Your Grandma’ is a potent Oedipal nightmare with a strong depiction of a stifling working-class existence: Tony and Jean left for London not to make their fortune but simply to try, unsuccessfully, to escape from the incestuous culture of their hometown. Like some of Welland’s other scripts, ‘Say Goodnight to Your Grandma’ also offers an interesting examination of masculinity. Tony and his friends seem unable to grow up; they are caught in the trap of nostalgia for their youth and the irresponsibility associated with it, and in reinforcement of this theme ‘Say Goodnight to Your Grandma’ uses 'The Teddy Bear's Picnic' several times during its narrative: the track first appears over the opening credits and, later, is used to reinforce the immaturity of the men's drunken behaviour at Tony's mother's house. Incredibly well-acted, ‘Say Goodnight to Your Grandma’ has a gritty honesty in its depiction of working-class family life and, especially, men in their thirties who are still in thrall to their manipulative mothers. ‘Office Party’ (50:31)

Written by Fay Weldon, ‘Office Party’ takes place in a bank. At closing time, a piano is delivered and it is revealed that a party is to be held by the employees in celebration of the retirement of the bank's manager (George Cooper). Meanwhile, as preparations for the party get underway Julia (Angharad Rhees), the secretary of the deputy manager (Peter Barkworth), telephones the local hospital for the results of a pregnancy test. She discovers that she is pregnant; the father is apparently one of her colleagues at the bank, a man named Paul (Ray Brooks). Weldon takes little time in establishing the employees dislike of the manager. As the manager declares to his deputy, 'They'll be glad to see the back of me. They want a new face, new blood, a new ogre to kick'. The manager is an anti-humanist, a man who privileges regulations over the human factor: at one point, he proudly relates a story of how he cancelled the overdraft of an elderly widow, declaring to his deputy that ‘Affection has no place in a bank [….] And sentimentality has no place in a bank. Where would we be, Richard, if we took pity on all bad accounts?’

Julia’s friend asks if Julia has told Paul that she is pregnant, but Julia asserts that ‘It doesn’t seem to have much to do with him’. Her friend tells her that ‘He’s the one that’s going to have to marry you’. Julia is unhappy with Paul, and their relationship amounts to nothing more than encounters in the bank’s stationery cupboard. Later, during the party, Julia discovers from another member of staff that Paul has been boasting about his breaktime liaisons with Julia; some of the other men in the bank seem to think that this gives them a licence to make moves on Julia – that she is a ‘loose’ woman. Julia confronts the unhelpful Paul, telling him that ‘Any decent man would be looking after me, being nice to me. But all you can do is make me feel as angry and as miserable and as horrible as possible’.

Meanwhile, the deputy manager’s wife begins to suspect that her husband has been having an affair with Julia, and that the baby is his: ‘I always knew about him and her, cooped up in that little office’, she states. Her suspicions are passed onto the manager, who confronts his deputy – resulting in the deputy manager, for the first time, standing up for himself in the presence of both his wife and the manager. ‘Office Party’ could be described as a proto-feminist drama. Weldon misses no opportunity to highlight the chauvinism of the bank’s employees, who pass judgement on Julia based on her low-cut dress: after Julia has rejected the advances of one of her male colleagues, he dismissively tells her, ‘You tart yourself up like that, you half undress yourself, and then you bleat about your soul’. Julia also discovers the circulation of an office pool in which the male members of staff must identify ‘the six girls you would most like to lay’. Julia expresses disgust at the pool, and in response one of the other (male) members of staff declares, ‘The minute a bird joins a committee meeting – bloody trouble’. When Julia tells the deputy manager that ‘What you need is a male secretary’, the deputy manager tells her, ‘Well, for your information, I would if I could’. ‘Well, why don’t you then?’, Julia asks. ‘Because they cost too much’ she is told: ‘And one has to pay for their dreary wives and children too’. ‘And they’re not so decorative either’, Julia reminds him. Even the women display elements of this chauvinistic attitude: Julia’s female colleague tells Julia that ‘You haven’t any judgement. Girls don’t when they’re pregnant’. When Julia is asked by her female friend if she ‘really want[s] to get married’, Julia responds by stating sarcastically, ‘Of course. A little husband, a little baby. Sounds like a game for little girls to me’. Her friend declares, ‘But you have to have a man. Otherwise you’ve failed’.

Julia’s predicament provokes a variety of responses from her colleagues, but most of them believe that she must marry Paul – despite her growing distrust of him. One of the other men tells Julia that Paul was not happy when he found out that Julia was pregnant; the man tells Julia that ‘Marriage is an old-fashioned institution. It’s too claustrophobic for a growing child. I mean, one man and one woman shut together in a private box. What kind of upbringing’s that?’ He suggests that he will ‘introduce’ Julia to ‘a commune’ where the inhabitants ‘live off the land’. ‘Office Party’ depicts a society in which men and women cannot relate to one another’s needs. As one of Julia’s female colleagues asserts, ‘I wish there was a great wall running down this country with the men on one side and the women on the other. Then, perhaps, we’d get some peace’. ‘Brown Skin Gal, Stay Home and Mind Bay-Bee’ (52:57)

Ruth (Billie Whitelaw) is a frustrated divorcee who makes a decision to convert the ground floor of her house into a flat. She rents it to a Dublin-born electrician, Roger Pentecost (Donal McCann), who it seems has until recently been living a sheltered life in his mother's house in Stockport. After Roger's lodgings with Ruth have been established, one of Roger’s colleagues suggests he make moves on Ruth: ‘It’s the new permissive society. Skin it, grab it, feel it, get yer bleedin’ ‘ands round it. Get in there, boy’. As if in confirmation of this, when Roger asks to read one of Ruth's books, Ruth lends him a novel by Henry Miller, referring to it as 'quite... impressive'. Eventually, Roger begins to experience daydreams about Ruth, and Ruth begins to daydream about Roger. These begin with simple erotic fantasies but progress to both of them daydreaming about marrying one another. However, the erotic charge of Roger and Ruth’s fantasies is offset by the banal dialogue between the two, and the potential of their relationship remains unfulfilled.

Nevertheless, Roger lies to his friend, telling him that he’s been ‘getting his greens’ from Ruth; in fact, every time Roger has been presented with the opportunity to seduce Ruth, he has retreated into himself. Following a drunken encounter with a young woman, who he brings back to his flat, Roger finds himself on the receiving end of Ruth's scorn; Ruth is clearly disappointed in Roger's choice of 'playmate'. Soon, Roger moves out of the flat, having acquired work elsewhere. Billie Whitelaw plays Ruth as an attractive and strong-minded modern woman, financially independent and openly appreciative of her enjoyment of Henry Miller's work. Her experience of the world is signified through her status as a divorcee. On the other hand, Roger is a repressed and inexperienced man; there is more than a hint that he has been something of a 'mother's boy', and that his encounter with Ruth has awakened the sexual desire that he has for so long repressed. The erotic daydreams that Ruth and Roger experience have a potency, being based on little more than the caress of a hand. These soon progress to more elaborate fantasies of love and marriage. However, the potential of the relationship between the two is continually thwarted: neither Ruth nor Roger has the courage to act on their desire, their proximity in the same house seemingly both feeding and suppressing their attraction to one another.

'Brown Skin Gal, Stay Home and Mind Bay-Bee' is an effective and often claustrophobic drama about repression and desire, with a progressive depiction of the life of an independent woman offset by its representation of masculinity: Roger is sexually-repressed and emotionally immature, and there is the suggestion that his friend – the only other significant male character – is nothing more than a braggart. Eventually, Roger settles for a meaningless casual relationship with an undemanding and naïve younger woman. The suggestion is that men are unable to meet and satisfy the emotional and sexual needs of modern women. In its examination of this theme, the play is uncharacteristic of the work of its author Robert Holles, a writer generally associated with war-themed fiction (as per his script for the 1964 film Guns at Batasi, based on Holles’ 1962 novel The Siege of Battersea). ‘Detective Waiting’ (52:58)

‘Detective Waiting’ opens with a handheld point-of-view shot from inside a moving car; from the outset, this drama establishes the cinema verite-style camerawork associated with contemporaneous films like The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1972), which is an acknowledged influence on Ian and Troy Kennedy-Martins' 'Regan' (for Armchair Cinema) – the one-off drama that would eventually lead to the creation of The Sweeney (Thames/Euston Films, 1974-8). Ian Kennedy-Martin's work is associated with the genre of crime drama, but ‘Detective Waiting’ is very different from many of Kennedy-Martin's other contributions to this genre. ‘Detective Waiting’ focuses on a young police detective, Lewis (Richard Beckinsale). Softly-spoken and clearly intelligent, Lewis is bullied by his colleagues and is seen as something of an outsider. Early in the drama, Lewis is called to a meeting with the superintendent who, speaking in clipped tones, tells Lewis that ‘People are not very fond of you, Lewis [….] They don’t like you. Attitude? Selfish [….] People don’t like you. They say you’re arrogant [….] You’re arrogant, cunning […] They say you’re moody; you think too much; you reject the comradeship of your fellows; you’re out on your own [….] They distrust you. Stuck up’.

Lewis is given the job of trailing James Anthony Edward Cummins (Barry Linehan), a man convicted of larceny and sentenced to seven years. Following his release from prison, Cummins is suspected of stealing three lorry loads of French brandy, totalling £20,000. Lewis pesters Cummins (telling him at one point that, ‘I’m entitled to sit here and watch you day and night, and night and day’). Eventually, it is revealed that the superintendent’s plan is to place the unliked Lewis in a situation where he aggravates Cummins to the point that Cummins assaults him, thus giving the police an opportunity to arrest Cummins: as the superintendent tells one of his colleagues, ‘Cummins is going to lose his short temper [and] kick Lewis over the pavement and impale his head on some railings. Then for the first time in ages, we’ll have a real excuse to grab him’. Aggravated by Lewis’ presence, Cummins blackmails a local councillor into persuading the superintendent to call Lewis off the case. Eventually, when this doesn’t work, Cummins resorts to having Lewis ‘roughed up’ by one of his associates, and whilst Lewis is knocked to the floor a photographer takes several pictures of Lewis being kissed by a young woman – who, it is later revealed, is the girlfriend of one of Cummins’ competitors, Tony Blonde. Cummins also plants £2,000 in Lewis’ bank account; the plan is to make Lewis appear to be ‘the bent copper we could have used’ in the heist.

Benefitting from a great performance by Richard Beckinsale as the introspective and softly-spoken Lewis, Kennedy-Martin’s script goes to great lengths to outline the bullish chauvinism of Lewis’ colleagues. In the opening scene, a uniformed officer tracks down Lewis and sneers at an incident of infidelity at the police dance, which Lewis did not attend: ‘You should have gone to the dance. Sergeant Laker got off with Constable Coleridge’s wife, poor sod’, the uniformed officer asserts. Later, this exchange is echoed when the sergeant at the police station asks Lewis why he did not attend the dance. ‘I don’t dance, sir’, Lewis tells him. ‘I don’t dance, Lewis’, the sergeant replies; ‘You should have been there. We expect our youth to attend the social graces. Sergeant Laker got off with Constable Coleridge’s wife. Poor slob’. As if to underscore the boorish attitude of the other police officers, when the sergeant asks Lewis if he is married, and Lewis replies in the negative, the sergeant tells him ‘That’s the way to be boy, and then you can spread it about a bit’.

We are given insight into Lewis through his narration; the almost hard-boiled content of Lewis’ voiceovers suggests that Lewis perceives himself as a Humphrey Bogart-esque figure: reflecting on Cummins whilst observing the criminal at the golf course, Lewis reflects: ‘I bet he’s tough as cold cord’. However, Lewis seems simply to seek the respect of his colleagues. When asked by the superintendent what he wants from life, Lewis replies simply that ‘I want to do what I do correctly, because then I’ll have respect and I want to respect myself and I want to have the respect of others’.

Kennedy-Martin’s script draws parallels between Cummins and the superintendent, both of whom are about the same age. In different scenes, both Cummins and the superintendent express to Lewis nostalgia for the past. In one scene, the superintendent reflects on when he made the rank of detective at the age of thirty-six: ‘Beer was browner then, Lewis. Crime was blacker. Not like the crime today, all grey and convolved’. Later, his comments are reflected in Cummins’ angry response to Lewis’ suggestion that he has a ‘hunch’ that Cummins is involved in the theft of the brandy: ‘You young coppers. You get hunch diarrhoea [….] Not like the coppers ten, fifteen years ago. The first thing they did was thump you. Then they took you down to West End Central and thumped you again. Then they asked the questions’. A provocative drama with a bitter view of humankind – all of the characters are in some way manipulated and exploited; as Cummins tells Lewis, ‘Life is a game of monopoly where everyone cheats’ – ‘Detective Waiting’ benefits greatly from the presence of Richard Beckinsale. However, Kennedy-Martin’s script arguably tries a little too hard to be experimental in its use of dialogue, deploying heavy doses of phrase repetition and clipped syntax, especially in Lewis’ meetings with the superintendent. Nevertheless, ‘Detective Waiting’ is interesting for the way in which it abandons the conventions of the police procedural. ‘Will Amelia Quint Continue Writing “A Gnome Called Shorthouse”?’ (53:23)

Written by Roy Clarke, a writer strongly associated with the genre of the television situation comedy thanks to his creation of Open All Hours (BBC, 1976-85) and Last of the Summer Wine (BBC, 1973- ), ‘Will Amelia Quint Continue Writing “A Gnome Called Shorthouse”?’ opens with Lewis Denholm (Richard Vernon), owner of the Denholm Publishing Company, deciding that he must attempt to persuade Amelia Quint (Beryl Reid), an author of children’s books featuring the character of a gnome called Shorthouse, to start writing again – simply because ‘She was wholesome and profitable. That’s quite a trick, you know’. Quint is in retreat in Italy, spending her time with two Italian gigolos, Giulio (Norman Rossington) and Nico (David Warbeck). Quint has abandoned her career as an author, seeing the children’s novels as an unnecessary agent of repression. She displays particular hatred towards her fictional creation, Shorthouse: when told that the children miss him, she replies by asserting ‘They don’t miss that porridge-filled little pillock: it’s the mums that foist him on them’.

Nevertheless, Denholm and his assistant Miles (Geoffrey Chater) succeed in persuading Quint to return to England. However, she refuses to leave Nico and Giulio behind – much to the humiliation of Denholm, who seeks to ‘keep her reputation untarnished [….] Half the juvenile nation has been brought up on these creatures [the gnomes in Quint’s books]. We have a sacred duty to preserve the odour of sanctity that emanates from this pot-bellied little prat [Shorthouse]’. Denholm’s problems are compounded when it is revealed that a female journalist named Tindall (Sheila Steafal) is seeking to write an article about Quint; Denholm struggles to shield Quint’s new lifestyle from Tindall. A recurring theme in this drama is the conflict of attitudes towards the perceived move towards a culture of permissiveness. In fact, ‘Will Amelia Quint…’ opens with Denholm bemoaning the growth of the ‘permissive society’. Later, in a humorous scene, Denholm and Miles scornfully discuss an unnamed sex manual (presumably along the lines of The Joy of Sex, which had just been published in 1972): discussing some of the content of the book, Denholm muses to Miles, ‘Was that the one with the parallel bars?’ ‘No, the one with the garden equipment’, Miles responds. Later, Denholm and his associates find themselves having to deal with Quint’s wholehearted embracement of the permissive society, and the conflict between her ‘wholesome’ fictional creation and her association with the two Italian gigolos. At an event to promote her return to the arena of children’s fiction, Quint struggles to keep her real feelings about her work from the press.

Once in England, Quint finds that her farcical relationship with Giulio and Nico has changed and is no longer fun: ‘What used to be a lovely game in sunshine is now ridiculous here’. For Quint, England is a repressive society, and characters like Shorthouse help to perpetuate that repression: at one point, Quint asserts that ‘I can’t stand him [Shorthouse]. I loathe that smug, chubby, psalm-singing, sweet-sucking, rosy-cheeked, twinkling blue-eyed twit. I didn’t invent him: he lurks, fully-clothed, inside every decent English maiden’s gym slip, ready to press her embarrassment button or giggle pedal, the minute she has a vision of specific male regions. And it takes so long, if ever, to shift him’. At one point, a journalist claims that Quint’s work displays a subtext which suggests that Quint has ‘sadistic fantasies’ – a claim that superficially seems absurd until Quint admits her hatred of Shorthouse and the fictional world that she has created.

Witty and with a strong comic performance from Beryl Reid, ‘Will Amelia Quint…’ is an interesting satire of English attitudes towards sex and permissiveness. However, Quint’s rebellion against the repression within English society is also satirised: once she has returned to England, even Quint acknowledges that her relationship with Giulio and Nico is absurd – that it only makes sense in the sun-drenched and, to quint, exotic culture of Italy. Clarke’s play sharply suggests that repression is so ingrained in the psyche of the English that it is impossible to escape. ‘The Folk Singer’ (51:20)

Written by Dominic Behan, the brother of writer Brendan Behan, ‘The Folk Singer’ opens with stark documentary footage of Belfast city streets during the Troubles. This suggests a stark exploration of the ‘Irish problem’. However, this is thrown into relief following the opening credits: Danny Blake (Tom Bell), a folk singer, is in bed with his assistant Miss Arrowroot (Celia Bannerman) when he is woken by his manager, Eddie Reubens (Bernard Spear), who asserts that a bomb has been planted outside the hotel. When the bomb detonates, this causes an argument between the hotel staff and a group of workmen – a mixture of Catholics and Protestants – about whether the explosion was the responsibility of the Provisional IRA, who planted the bomb, or the British Army, who tried to defuse it. The argument is broken up by one of Blake’s band members, who distracts the hotel staff and workmen by singing ‘When Irish Eyes Are Smiling’ – and the hotel staff and workmen forget their argument to join in. As Blake observes, ‘The Irish don’t need drugs, Eddie: they have a natural imagination; they’re always on a trip’. Thus the tone is set for a blackly comic examination of the Troubles.

At dinner, Blake pokes fun at a group of visiting American psychiatrists, led by Professor Malone (Bill Nagy), who – unable to understand the irony in Blake’s assertions – praise him when he sings a song for them. When a bus is blown up by the IRA, the visitors are trapped in the hotel. The hotel’s manager (Allan McLelland) complains to Blake that his cabaret won’t be taking place as the ‘artistes’ have been arrested for wearing what ‘they thought was “with it” gear for the Belfast scene’: ‘balaclava helmets and stocking masks’. Blake offers to sing for the guests, but finds that during the show the hotel staff take sides and the Protestants and Catholics refuse to mingle with one another.

After it is disrupted by a man dressed as Christ and carrying a cross (provocatively listed in the credits as ‘Jesus Freak’ and played by Tim Hardy), Blake’s show is eventually cancelled because he cannot prove whether he is a Protestant or a Catholic: Blake is in fact an atheist. The British Army enter the hotel and arrest the staff; this action causes the desk clerk to blurt out that ‘The peace makes are all here to shoot us or intern us all, in the name of tolerance’. Blake is arrested under the Race Relations Act for singing a Christian hymn in the presence of a Jewish man – the aforementioned ‘Jesus Freak’. However, the hotel waiter reminds the man who arrests Blake that the Race Relations Act doesn’t stretch to Northern Ireland: ‘Race relations here? Sure, what in the name of God would we want with a Race Relations Board in Belfast?’ Behan’s script paints in broad strokes, deploying recognisable stereotypes and often skewering them: Behan’s contempt seems to be reserved for the visiting Americans, who don’t understand the situation in Northern Ireland but seem intent on offering opinions about it (and who don’t seem to comprehend irony). At one point, the hotel waiter (J. G. Devlin) tells a complaining American visitor, ‘Well, you could go further, sir, and fare worse [….] You could be like the British Army, sir: they’re right in the middle of it. The poor fellows don’t know who’s going to throw a bomb at them. You see, Protestants and Catholics look so much alike, sir: you couldn’t tell one from the other’.

‘The Folk Singer’ is a provocative drama: although Behan’s sympathies in real life were with the Republican cause (both Dominic Behan and his brother Brendan Behan has associations with the IRA, their father Stephen reputedly being a member of Michael Collins’ special assassination squad, the ‘Twelve Apostles’), ‘The Folk Singer’ skewers all of the participants in the conflict: both the British and the Irish are depicted as bumbling and incompetent. ‘The Folk Singer’ is an absurd reflection of the situation in Northern Ireland, seemingly designed to court controversy (especially with the appearance of the ‘Jesus Freak’). The humour is black and coarse, and some may find it a little tasteless. However, it is a provocative and interesting take on an issue that, in the early 1970s, was still something of a cultural hot potato. ‘A Bit of a Lift’ (52:24)

Opening in a church in which preparations are being made for a wedding, ‘A Bit of a Lift’ quickly introduces Alec Gardner (Ronald Fraser), the solicitor of the couple being married, and thirty-something divorcee Penelope (Anne Beach). Sitting next to Penelope, Alec quickly makes moves on her, with the aim of getting her into bed. Meanwhile, Frank (Donald Churchill) enters a public booth to make a recording for his wife. The recording is intended to serve the function of a suicide note: ‘I just thought that I would send you this record, Brenda, instead of leaving you a suicide note, because it would be the first chance I’ve ever had of talking to you for three minutes without you interrupting me’. Frank plans book a room at a hotel and overdose on sleeping tablets. Brenda is, according to Frank, a ‘nagging cow’ who has been having an affair with a man called Sid for nineteen years. In the recording, Frank tells Brenda that ‘I know that you will join with me in hoping that this last act of mine will be a little bit more successful than my attempts to earn my living over the past few years’.

At the wedding reception Alec succeeds in persuading Penelope to engage in a liaison at the hotel; they book into the hotel under false names, masquerading as ‘Dr and Mrs Windsor-Brown’. In the hotel room, Alec realises that he is more tipsy than he thought, and excuses himself so that he may go to the lavatory. However, the drunken Alec soon finds himself lost in the hotel’s maze of corridors and, forgetting the number of the room he is sharing with Penelope, ends up in the room in which Frank has booked.

Frank offers Alec a drink, and Alec tells Frank about Penelope, who he describes as ‘this lovely divorcee who hasn’t had it for years’. After sharing a drink with Frank, Alec leaves Frank’s room but finds himself lost again. Returning to Frank’s room, Alec asserts that he plans to telephone the reception desk to ask what his room number is. However, he realises that he has ‘forgotten the false name I gave when I registered’. ‘I used a nom-de-plume’, Alec tells Frank. ‘Or in this case, a “nom-de-crumpet”’, Frank jokes. Alec tells Frank that he believes that the name he gave was ‘Dr and Mrs… and then some kind of a soup. Or was it an hors d’oeuvre?’ Frank travels down to the reception desk for Alec and manages to acquire the name that Alec used when booking the hotel room. However, rather than giving this information to Alec, Frank returns to Alec’s room and, with the lights off, takes Alec’s place, participating in a tryst with the unknowing Penelope. Frank is given a new lease of life, and returns to his room to give Alec the room number.

When Alec returns to the room, Penelope declares that ‘you really are super… at “it” [….] You’re so tender, so sensitive. You really do make a woman feel so marvelous’. ‘But I haven’t done anything’, Alec protests as Penelope prepares to leave for her home in Banbury. Written by Donald Churchill, ‘A Bit of a Lift’ juxtaposes the wedding with the unhappy marriage of Frank, and Alec and Penelope’s cynical attitudes towards marriage. (Both Alec and Penelope have been through divorces.) During the wedding ceremony, as the vicar asks if anyone has objections to the wedding, Alec confesses to Penelope that ‘I always want to shout out at this point, don’t you. You know, shout out: “Stop, stop, that’s my wife Frida you’re marrying”’. Reflecting on his divorce, Alec asserts that, ‘We divided the house into two. Not easy. The marriage split up easier than the house. It’s now two flats, with two doorbells’. Meanwhile, Frank is unhappily married to a woman he refers to as a ‘nagging cow’, and who has been participating in affair with Frank’s friend Sid. Churchill and Fraser play their roles well, with Fraser playing Alec as a pompous, arrogant character. ‘A Bit of a Lift’ teasingly hints at the very different class backgrounds between the two men, with Frank telling Penelope that ‘I don’t blame you for fancying that lawyer bloke. He must be very attractive to women, in his middle-class, arrogant way’. However, this potentially rich vein of comedy is underplayed in the scenes between Frank and Alec, and the scenes that Churchill and Fraser share are filled with frustrated comic potential. Nevertheless, Churchill and Fraser are never less than watchable. ‘Red Riding Hood’ (52:10)

Written by John Peacock, ‘Red Riding Hood’ reimagines the classic folk tale as a modern fable of greed and irresponsibility. ‘Red Riding Hood’ opens with a scene depicting Grace (Rita Tushingham) and her grandmother, Thelma Maynard (Hilda Barry). Grace visits her grandmother once a week, and the opening shot depicts Thelma greedily eating cake whilst Grace looks on. ‘Every week, Grace’, the old woman says; ‘You spoil me. Every week’. The exaggerated sound of a ticking clock is heard, a non-diegetic sound that recurs throughout the narrative, symbolising the passing of time and Grace’s sense of her lost youth. Grace asks her grandmother for money, and her grandmother replies by telling her that ‘If I had any money to spare, you could have it’. Grace turns her face away when her gran asserts, ‘You’re such a good girl, Grace’.

At home, Grace receives a final rent demand. She lives with her elderly father (Arthur Hewlett), taking care of him. He is completely dependent on her. Grace decides to keep the final rent demand from him, telling him that it was ‘Only a letter’. Grace clearly feels trapped and stifled by caring for her father. She is also clearly in financial difficulties. Her life is one of repression, conveyed by her job as a librarian. Meanwhile, at work, Grace stares longingly at Henry George (Keith Baron), the man who makes home deliveries of books for those unable to come in to the library. As Grace asks if she can leave early to visit her grandmother, the credits play out over a series of tableaux depicting scenes from the ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ folk tale. Following the credits, Henry is shown playing a piano in a house that we later learn belongs to Mrs Maynard. Henry notices some blood on his hands and licks it from his fingers; he then answers the door to a delivery of groceries for Mrs Maynard and, paying for the groceries, he tells the delivery boy that ‘Mrs Maynard will be away for a fortnight’. Meanwhile, Mrs Maynard’s dog Gypsy whines in the kitchen. Later, as the non-diegetic clock ticks on the audio track, Henry’s hand wanders over a series of objects on a bedroom dresser before he looks in a mirror and sees there a bed with a bloodied arm hanging out of the sheet. The arm belongs to Grace’s grandmother.

When Grace returns home, Grace’s father questions Grace about the letter, and she reveals that they owe six months rent. ‘What are we going to do?’, her father asks. Grace determines to visit her grandmother and ask for money. However, when she gets to her grandmother’s house she discovers Henry is there – but there is no sign of her grandmother. Grace and Henry drink some of Mrs Maynard’s sherry, and Grace admits to Henry that ‘I’ve worked in the library for ten years. Everyone that you don’t want to talk to you goes and bores you stiff. They’re always coming up to you, and they start discussing the latest banality of a book or whatever. “Why me?” I ask [….] Situations like that, you can’t get away. I stand there nodding and smiling and being oh, so charming. Bored silly, trapped. Just because I’m so bloody feeble that I haven’t got the nerve to say what I really want to say’. She reveals that she tried to resign from her job at the library, but she was told to ‘Take a day off and think it over, Grace’.

Grace is over thirty and feels that time has passed her by: ‘There are so many things I wanted to do, so many places to see, things to achieve. I spent ten years saying, “Never mind, Grace. They’ll still be there tomorrow” [….] In the library, I thought, “If only I could scream. If only I could do something outrageous, not just to draw attention to myself but to give me one big embarrassment to cope with. Somehow I thought that would take my mind off all my little problems. If I did something like that, I wouldn’t have to pretend to be nice anymore; I wouldn’t have to pretend to be charming [….] Sometimes I’ve said obscenities so loudly to myself in my mind that I’d thought I’d spoken them. I hadn’t, of course’. Sensing Grace’s unhappiness, Henry offers her a proposition: she may spend a fortnight at her grandmother’s house, effectively abandoning her responsibilities. ‘You could spend your whole fortnight doing whatever you wanted to do, deciding’, he tells her: ‘Nobody would bother us’. As if in reminder of the consequences of Grace’s decision, when Grace decides to stay a close-up of her face dissolves into a shot of her bedridden father, in a darkened room, crying ‘Where are you?’

Grace and Henry help themselves to Grace’s grandmother’s money. One day, whilst Henry is out of the house, Grace finds the cane that it seems was used to murder her grandmother, and she finds spots of blood on the floor underneath her grandmother’s bed. However, Grace does not mention this to Henry. Over the next few days, Henry and Grace’s behaviour becomes increasingly raucous. At the end of the fortnight, the doorbell rings symbolically. ‘Please, one more week. That’s all’, Grace begs Henry. However, Henry must leave. ‘No’, he tells her firmly, like a parent to a child. ‘Please, please’, she begs before the screen is dominated by a montage of disconnected shots that signifies the fragmentation of Grace’s mind. ‘I can’t go back to that’, she screams at Henry. He makes her stab him, as if he were an intruder. As he dies, he tells Grace to scream, but when she opens her mouth she find that no sound comes out. From a close-up of her face as she screams silently, we cut to a shot of her collapsing in front of an illustration of Little Red Riding Hood in the children’s section of the library in which she works.

Truly the gem in this set, ‘Red Riding Hood’ is an ambiguous and fascinating entry into the Armchair Theatre strand: the murder of Grace’s grandmother is never fully outlined (it is not confirmed that Henry killed Mrs Maynard: we are simply shown him covering up her death), and in fact the closing moments suggest that the whole scenario may be nothing more than Grace’s fantasy. In this reworking of a classic folk tale, Henry (the wolf) represents the freedom from responsibility that Grace desires, and the sexual threat that the wolf symbolises in the folk tale is present throughout the latter half of ‘Red Riding Hood’.

The episode is filled with potent and haunting Freudian imagery, from the shot of Henry looking at Mrs Maynard’s body in the mirror on the bedroom dresser to Grace’s visualisation of bath filling with blood. The characters are tragic: Henry is seductive but has a self-destructive impulse, and Grace is both naïve and irresponsible – her gleeful abandonment of her elderly father is unforgivable. The episode reworks the classic folk tale as a kitchen sink nightmare, and the outcome is a traumatizing, powerful hour of television. In its selfconscious reimagining of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, with its hints that Grace is sexually repressed, ‘Red Riding Hood’ is comparable to Angela Carter’s postmodern attempt (in her 1979 book The Bloody Chamber) to ‘extract the latent content’ from traditional fairy tales (Haffenden, 1985: 80).

Video

These episodes of Armchair Theatre are predominantly shot on videotape, with some filmed inserts. On the whole, the episodes are well-preserved but show some evidence of tape damage, with some episodes (‘Office Party’ and ‘The Folk Singer’) faring worse than others. Nevertheless, they are never anything less than watchable. The original break bumpers are intact throughout all of the episodes, and the episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. The episodes all appear to be intact, with no evidence of cuts.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track. This does not cause any problems and is clear throughout. There are no subtitles.

Extras

Sadly, there is no contextual material. Interviews or biographies would have been nice…

Overall

A fantastic release, this set contains a wide variety of episodes from the Thames era of Armchair Theatre. There is probably something here to please everyone, from black comedy to domestic drama. The highlight of the set is arguably John Peacock’s ‘Red Riding Hood’, although ‘Office Party’ and ‘Say Goodnight to Your Grandma’ are also very impressive. Let’s hope that Network will release some more episodes of this series in the future. References: Cooke, Lez, 2007: Troy Kennedy-Martin. Manchester University Press Duguid, Mark, 2003: ‘Armchair Theatre (1956-74)’. Screenonline. [Online.] www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/534786/index.html Accessed: January 2010 Haffenden, John, 1985: Novelists in Interview. London: Methuen Sinfield, Alan, 1983: Society and Literature, 1945-70. London: Taylor & Francis Sydney-Smith, Susan, 2002: Beyond Dixon of Dock Green: Early British Police Series. London: I. B. Tauris Thumin, Janet, 2004: Inventing Television Culture: Men, Women and the Box. Oxford University Press For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing.

|

|||||

|