|

|

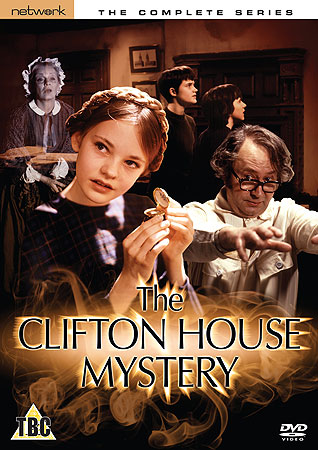

Clifton House Mystery (The) (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (5th February 2010). |

|

The Show

The Clifton House Mystery (HTV, 1978)

In ‘Dear BBC’: Children, Television, Storytelling and the Public Sphere (2001), Maire Messenger Davies suggests that children’s television drama suffers from a ‘lack of recognition’ which ‘is part of a general critical tradition which does not take seriously material specifically labelled as aimed at children’ (57). With some notable exceptions (for example, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland), children’s literature is still predominantly seen as a form of paraliterature: it exists outside the realms of the ‘literary’ and sits alongside ‘disreputable’ genres such as crime fiction. Like other paraliterary genres, children’s literature is seen as solely interested in the notion of escapism, demonstrating little form of social engagement or depth. Children’s television drama is similarly seen as being of ‘lesser’ quality than television drama produced for adults (ibid.). However, the perception of children’s television drama as being wholly escapist is undermined by the evidence: Maire Davies cites the BBC’s 1980s children’s serials Running Scared (1986) and Break in the Sun (1981) as examples of children’s television dramas that demonstrated a great deal of engagement with social issues. Running Scared dealt with crime, and Running Scared dealt with issues of racism (ibid.). Both of these series had a ‘gritty’ aesthetic that was grounded in use of real locations. Davies also suggests that an index of the lack of critical regard for children’s television drama is its relative absence from the medium of home video (ibid.). If children’s television drama is considered to have less prestige than adult television drama, then The Clifton House Mystery must be doubly disreputable: not only was it produced for children (‘You know, for kids’, as Tim Robbins’ Norville asserts in the Coens’ film The Hudsucker Proxy, 1994) but it also uses as its basis one of the most disreputable adult genres, the genre of the Gothic and the supernatural. However, The Clifton House Mystery demonstrates how children’s television drama can offer both escapism and social engagement in a way that, unlike many adult television dramas, is anything but precious. As will be discussed below, The Clifton House Mystery touches on the issue of class repression (specifically in relation to the 1831 Bristol Riots) within the framework of an engaging supernatural mystery – offering its youthful viewers a history lesson that completely avoids being ‘preachy’ by being firmly woven into an effective ghost story that features sympathetic characters and some truly memorable moments.

The Clifton House Mystery was produced in 1978 for HTV, the ITV contractor for Wales. In 1976, HTV delivered a similar series, The Georgian House; HHelen Wheatley (2006) states that both programmes ‘found children at the heart of Gothic narratives in which figures from the past returned to haunt them, channeled in both cases by a sinister haunted house’ (86). (In The Georgian House, two teenagers find themselves transplanted back to the 18th Century whilst visiting a reconstructed Georgian house in Bristol. There, they encounter a young slave, Ngo, who seems to be the only person who can help them to return to the 1970s.) Wheatley also notes that in the 1980s the BBC produced a number of similar adaptations of examples of Gothic literature in which ‘the child protagonist was transported through a haunted house or garden into a sinister past’: these included The Children of Green Knowe (1986), Moondial (1988) and Tom’s Midnight Garden (1989) (ibid.: 87). Wheatley argues that these children’s supernatural dramas appeared at a time when Gothic horror anthology series tailored for adults (such as Thriller, 1973-6, and Hammer House of Horror, 1980) were in decline. She suggests that from the mid-1970s onwards television drama became ‘dominated by nostalgic, big-budget classic drama series’ that were easier to sell to overseas markets ‘and socio-politically aware serial drama which had an inherent “seriousness” at polar opposite to the Gothic anthology series’ (ibid.). Thus, in the realm of adult television drama there was little room for ‘disreputable’ Gothic narratives. As a result, one of the few outputs for Gothic drama on television was the genre of children’s programming, and children’s television ‘produced a number of haunting Gothic serials during the late 1970s and 1980s’ (ibid.). Wheatley also suggests that adult Gothic Television dramas tended to situate their narratives in the present-day, and that Hammer House of Horror in particular ‘played on its status as television’ by ‘drawing on medium-specific representations of home and family’ (85). (This aspect of British Gothic Television was effectively satirised by the situation comedy The League of Gentlemen.) The same could be said of The Clifton House Mystery, which deploys the trappings of the domestic drama in its first episode, before introducing the supernatural elements that are at the core of the narrative. Taking place over six episodes, The Clifton House Mystery focuses on the Clare family: Timothy Clare (Sebastian Breaks), his wife Sheila (Ingrid Hafner), their daughter Jenny (Amanda Kirby) and their two sons Ben (Robert Morgan) and Steven (Joshua Le Touzel). Timothy is the conductor of the Bristol Chamber Orchestra, and he and his family are moving into a new home – which Timothy bought via auction from the elderly Mrs Betterton (Margery Withers). Along with her young granddaughter Emily (Michelle Martin), Mrs Betterton is moving out of the house, which has been in her family for over a hundred years. Mrs Betterton’s belongings are sold at an auction that takes place in the house, and Steven uses his Christmas money to buy a box containing what appears to be a mid-19th Century cavalry helmet; meanwhile, Tim finds himself drawn to a large painting that depicts a cavalryman, on horseback, in front of a raging fire. Against the wishes of his wife, Tim buys the painting and hangs it over the fireplace in the living room.

The Clares meet Mrs Bretterton and Emily; Emily gives Jenny a small music box, telling Jenny that ‘the lady […] wouldn’t like it if I took it out of the house [….] You mustn’t be afraid of her: she’s very kind’. That evening, whilst Steven obsessively cleans the helmet he has bought, Tim finds himself compelled to play a piece of music on the piano. ‘I don’t know what it is’, he tells Sheila; unbeknownst to Tim, the tune is the same piece of music that plays when Jenny’s music box is opened. Later that night, Ben and Steven witness the appearance of a ghostly face (Derek Graham) underneath the cavalryman’s helmet, which Steven has placed on the dressing table in the bedroom that the two brothers share. The next day, Steven and Ben spot an old window on the side of the house, almost hidden by creeper vines. However, there doesn’t seem to be a room with a window on that side of the house. Steven and Ben infer that the room has been bricked up and begin searching for an entrance to it, eventually finding it behind the wardrobe in their bedroom. As they break through the wall of the bricked up room, the ghostly lady (Elizabeth Havelock) that Emily mentioned appears to Jenny. Behind the wall, Tim, Ben and Steven discover another bedroom, which appears to have been concealed for a long time. The room contains a table, with a glass and candelabra atop it, and a bed. Tim pulls black the blanket on the bed and discovers a skeleton; he hurries Ben and Steven out of the room.

In an attempt to impress a prospective client, Mr Spangler, who may offer Tim ‘a nice fat American tour with nice fat American dollars’, Sheila and Tim invite Spangler (Oscar Quitak) and his wife Myrna (Olga Lowe) for dinner. Myrna Spangler notices the painting Tim bought. Identifying it as a representation of the 1831 Bristol Riots, Myrna tells Tim and Sheila that the riots ‘were all to do with workers rights and labour unions [….] And the right to vote'. Working class protesters, angered over the decision to deny them the vote, gathered in Queen Square and 'over a hundred people were killed when the soldiers fired on them, in a single night. Some of your loveliest old buildings were burnt to the ground'. As Mrs Spangler discusses the riots, a pot falls from a shelf in the kitchen; later, the Spanglers hurriedly leave the Clare family’s house when what appears to be blood drips from the ceiling onto Myrna’s face. The Clares discuss the discovery of the room, and the skeleton, with Mrs Betterton. They come to the decision to talk to the local vicar before approaching the police, to ensure that the remains have a Christian burial. Sheila proposes moving out of the house, but the children refuse, telling her that they like their new home. However, their interest piqued by the supernatural phenomenon they have witnessed, Ben and Steven decide to attend a lecture by a visiting ‘ghost hunter’, Milton Guest (Peter Sallis). After the lecture, they approach Guest, who is excited at the prospect of witnessing a ghost first-hand. (‘Usually I'm called in after it's all over’, he tells the brothers, ‘but this is still happening'.) Arriving at the Clare house, Guest asserts that 'It is absolutely vital that its spirit be laid to rest before the skeleton is removed from this house, or the house will still be haunted, even after the bones have been taken away'. Spending the night in the room with the skeleton, Guest witnesses a wounded officer being tended to by the elderly lady that Jenny has seen. Determined to discover the identity of the ghosts, Guest conducts some research and discovers some more details of the history surrounding the Bristol Riots of 1831; it seems that the ghost is likely to be that of Captain Bretherton, the commanding officer of the Dragoon guards, who were sent to Bristol to quell the riots. Bretherton refused to order his men to fire on the rioters, preferring to use other methods to try to prevent the riots from escalating, and was court-martialed for neglect of duty. However, Bretherton disappeared before the end of the second day of his court-martial. Guest surmises that Bretherton returned home, to the Clares’ house, where his mother lived. Bretherton’s mother tended to her son’s wounds, and when he died, she bricked up the room because she was scared of reporting her son’s death (due to his status as a deserter).

Guest plans to exorcise the house and is sealed in the room with the skeleton. Guest’s attempts to pacify the house’s spirits seem to be successful, but when Tim appears on a local television show and questions the existence of the spirits, the supernatural events begin again. Like many of the adult supernatural dramas produced for television in the 1970s, The Clifton House Mystery opens as a domestic drama and introduces its supernatural elements right at the end of the first episode. The narrative is grounded in historical fact: its description of the Bristol Riots is accurate, making a commendable attempt to raise the profile of an episode in British history in which the working classes were still fighting for the vote – something that many of us take for granted today. The story of Bretherton’s court-martial and his disappearance is accurate, but the historical figure who Bretherton represents was in real life named Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Brereton. Unlike Bretherton, Brereton did not disappear but rather shot himself before his court-martial ended. The Clifton House Mystery manages to integrate its historical detail in a compelling narrative that is well-supported by strong performances by all the cast, especially the young actors playing the Clare children and Peter Sallis, who turns in a memorable performance as the eccentric, childlike ghost hunter Milton Guest. There’s a certain arch self-awareness of the conventions of the ghost story (at one point, Tim tells Sheila, ‘Darling, don't be silly. Haunted houses belong to books, with ghoolies and ghosties and long-legged beasties and things that go bump in the night. There's nothing like that here'), but the supernatural elements are introduced in a chilling manner – and the regimental march that Jenny’s music box plays, and which accompanies the closing credits of each episode, is genuinely haunting. The result is a children’s television drama that is both informative, demonstrating an engagement with a specific historical event of which many of its young viewers would have been unfamiliar, and entertaining; in fact, The Clifton House Mystery can be favourably compared to the BBC’s ongoing Ghost Story for Christmas (1971-8) strand, which featured several adaptations of M R James’ stories (‘The Stalls of Barchester’ in 1971, ‘A Warning to the Curious’ in 1972, ‘Lost Hearts’ in 1973, ‘The Treasure of Abbott Thomas’ in 1974 and ‘The Ash Tree’ in 1975). Like James’ work, The Clifton House Mystery features a narrative that revolves around a traumatic and repressed past event breaking through into the present. (The most obvious parallels are between The Clifton House Mystery and the 1975 BBC adaptation of James’ story ‘The Ash Tree’, both of which feature a similar cross-hatching of past and present events.)

Episodes: Episode 1 (25:20) Episode 2 (23:04) Episode 3 (25:26) Episode 4 (25:07) Episode 5 (25:25) Episode 6 (24:02) Image Gallery (1:28)

Video

The Clifton House Mystery was shot wholly on video in a studio environment. The episodes are incredibly clear. There is almost no tape wear present, and the image is detailed and displays strong contrast. On the whole, the presentation is excellent.

The original break bumpers are intact, and the series is presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two channel track, which is balanced and always audible. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole extra is an Image Gallery (1:28).

Overall

An effective and haunting supernatural drama that also manages to be informative, The Clifton House Mystery is a rare treat – especially in these days in which children’s television is dominated by either animated series or situation comedy-type shows. Filled with some haunting imagery and some great performances, especially that of Peter Sallis, The Clifton House Mystery should satisfy young viewers interested in ghost stories, and there is also enough here to entertain adult viewers. This surprisingly little-discussed series is a real treat. References: Davies, Maire Messenger, 2001: ‘Dear BBC’: Children, Television, Storytelling and the Public Sphere. Cambridge University Press Davies, Maire Messenger, 2005: ‘”Just that kids’ thing”: the politics of “Crazyspace”, children’s television and The Demon Headmaster’. In: Bignell, Jonathan & Lacey, Stephen, 2005: Popular Television Drama: Critical Perspectives. Manchester University Press: 125-42 Wheatley, Helen, 2006: Gothic Television. Manchester University Press For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|