|

|

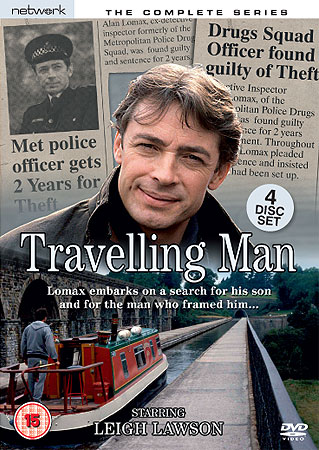

Travelling Man: The Complete Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th February 2010). |

|

The Show

Travelling Man: The Complete Series

Created by Roger Marshall and produced for Granada Television, Travelling Man (1984-5) features Leigh Lawson as Lomax (sometimes called ‘Max’ by the characters he befriends), a former member of the Metropolitan Police’s drug squad who was framed for the theft of £100,000. In the first episode, ‘First Leg’, Lomax is released after serving two years in prison, and finds that his wife Jan has moved to Canada, and his son Steve has taken to the road. Lomax’s house has been sold by Jan, and all Lomax’s wife has left Lomax is ‘Harmony’, his canal boat. After leaving prison, Lomax takes it upon himself to clear his name and find Steve. Lomax travels through the British countryside on his canal boat, and in each episode he finds himself at the centre of a different narrative: in ‘First Leg’, the first episode of the series, Lomax helps a middle-class drug addict, Sally Page (Morag Hood), through confronting her dealer (Peter Faulkner); in ‘On the Hook’, Lomax is caught in an incident of cattle rustling and, to clear his name, enlists the help of a man who he met in prison, a fence named Granny Jackson (Tom Wilkinson). Along the way, Lomax begins a relationship with Andrea (Lindsay Duncan) after she approaches him in a country pub; Andrea follows Lomax on a number of his adventures.

The structure of Travelling Man follows the model most popularly defined through the classic American series The Fugitive (ABC, 1963-7). The central premise of The Fugitive was Dr Richard Kimble’s (David Janssen) attempts to find the one-armed man who killed his wife Helen; each episode would find Kimble, on the run from the police, relocated to a different part of America. Kimble’s nomadic quest was always in the background of the series, with each episode focusing on a self-contained narrative, a moral conundrum that Kimble would be required to solve before moving on to another town. In The Philosophy of TV Noir, Aeon J. Skoble (2008) asserts that ‘each episode of The Fugitive is a self-contained morality play, in which the protagonist’s ongoing story intertwines with another tale concerning the people he has become involved with’: in each episode, Kimble is faced with a moral problem, ‘[c]an he do the right thing in his interactions with others while at the same time avoiding detection by the authorities?’ (84). In the 1970s and 1980s, the structure of The Fugitive would form the basis of many American television shows that sought to marry an ongoing narrative with a predominantly episodic format. American shows which featured a similar structure to The Fugitive included Kung Fu (Warner, 1972-5), Run For Your Life (NBC, 1965-8), Highway to Heaven (Michael Landon Productions/NBC, 1984-9), Quantum Leap (Belisarius Productions/Universal, 1989-93) and The Incredible Hulk (Universal, 1978-82), in which Dr David Banner (Bill Bixby) travelled through America, fleeing from dogged National Register reporter Jack McGee (Jack Colvin). Banner faked his own death after a lab explosion which killed his research partner, Elaina Marks (Susan Sullivan), and Colvin knows Banner’s secret: when he experiences rage he transforms into the monstrous green-skinned Hulk (Lou Ferrigno). In each episode, Banner would be in a different town or city, and he would be maneuvered into a situation in which he must help an innocent party (for example, an arcade owner threatened by the rackets, in the first season episode ‘Terror in Times Square’) or solve a crime (eg, the second season episode ‘Escape From Los Santos’).

Although The Fugitive is credited with popularising this type of character in the world of television, the character of the loner-on-the-lam did not originate with the series: producer Quinn Martin once claimed that he saw the series as ‘a modern-day retelling of [Victor Hugo’s] Les Misèrables’ (Etter, 2003: 33). In a 1965 article for Life magazine, published to coincide with the beginning of the third season of The Fugitive, critic Richard Schickel asserts that ‘a man on the lam escaping an alleged crime, is one of the archetypal figures of our popular culture, splendidly personified by the good-bad man [silent film star] William S. Hart created for the silent movies a half centure ago’ (27). According to Schickel, this character type ‘has been a staple Western character ever since’, played by actors such as Chuck Connors in the Western drama Branded (1965-6), which was created by Larry Cohen and used the persecution of the West Point officer Captain Jason McCord (Chuck Connors), falsely accused of cowardice, as a metaphor for the McCarthyite witch-hunts in the 1950s. However, Schickel claims that The Fugitive’s master stroke was in ‘the relocation of the mythic hero in the modern world’ (ibid.). For Schickel, this character had two functions: he romanticised ‘the loneliness all of us sometimes feel in a mass society’ and also ‘proved that escape is still possible, no matter how crowded or overorganized things seem to be getting’ through celebrating ‘[t]he open road, the freedom to move on’ (ibid.). Travelling Man takes the basic structure of The Fugitive and its romantic depiction of an anti-hero who represents a flight from the trials and tribulations of modern life. However, where the various American series modeled on The Fugitive, in Schickel’s words, celebrated ‘the most treasured [of] American traditions’ (the ‘open road’) (ibid.), Travelling Man moves the formula away from the Americanised association of roads and freedom, allowing Lomax to instead use canals to travel around Britain. Although the concept of the canal was not invented by Britain, it is a mode of transportation that symbolises British culture thanks to the historical use of Britain’s natural waterways to transport goods during the Roman occupation and, later, the Industrial Revolution. In more direct parallels with The Fugitive, like Richard Kimble Travelling Man’s Lomax often finds himself at the centre of a witchhunt (in ‘The Watcher’, he is caught in the eye of the proverbial storm after a seven year old girl is killed) or suspected of a crime (In ‘On the Hood’, Lomax is accused of rustling farm animals). Although on a superficial level, Travelling Man may seem to be nothing more than a relatively ‘light’ crime drama, there are some highly disturbing undercurrents in the show. In the second episode, ‘The Collector’, Lomax is stalked by Terry Naylor (Michael Feast). Naylor knows about Lomax’s past and believes that Lomax is in possession of the stolen money. Sneaking aboard Lomax’s boat, ‘Harmony’, at night (whilst Lomax is away visiting his ailing mother), Naylor disturbs Andrea, who has been taking care of Lomax’s narrowboat. Naylor douses Andrea’s bedsheets in petrol and threatens to set her alight, asking the bemused woman ‘Where’s he keep it?’ 'Pretty name. Pretty face. You ever seen anyone with multiple burns, Andrea? Now, that's not a pretty sight. Not pretty at all', Naylor threatens; 'Tell him I called [….] I'll give you something to remember. Okay?' He then sets light to the bed, and Andrea screams in terror.

In this particular episode, Michael Feast’s performance as Naylor brings to mind the giggling psychopath Tommy Udo (Richard Widmark) in the film noir Kiss of Death (Henry Hathaway, 1947). As the narrative progresses, we discover that Naylor makes a habit of pouring petrol on his victims’ bedsheets as they sleep, and then setting them alight. Investigating the attack on Andrea, Lomax consults a former colleague, Detective Chief Inspector Barbara Bramwell (Veronica Clifford), who tells Lomax that Naylor has ‘got form [….] He's a bullyboy, collector, protection, the rackets. Oh yes, and he likes to burn people, obnoxious little creep'. It is all the more surprising that, when Lomax confronts Naylor in his own home, we discover that Naylor is a domesticated married man; as Lomax dryly observes to Naylor’s wife Irene (Su Elliot), 'You should be proud of him. Very imaginative, pulls some very imaginative strokes', adding that Naylor’s methods of pouring petrol on his victims and then setting them alight are '[p]erhaps […] not the sort of thing you tell your old lady, eh. Not something to boast about'.

In the third episode, ‘The Watcher’, Lomax comes across an isolated Welsh village. Entering the village, where Steve has apparently been living rough with a couple of other teenagers, Lomax finds it deserted except for an elderly man in the local pub. The man tells Lomax that all of the village’s inhabitants are in the chapel; when Lomax asks why everyone has attended the chapel, the man tells Lomax that it ‘Depends if you want to work or not’. Apparently, the whole village works for a local magnate named Morgan Rees (Freddie Jones), who keeps the community isolated: Rees’ control of the village is comparable to Lord Summerisle's (Christopher Lee) ownership of the island community in The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy, 1973). The village’s community is insular, isolated from the outside world and suspicious of strangers. When a seven year old girl disappears and is found murdered, suspicion of guilt immediately falls upon Lomax, and the local policeman (Hubert Rees) railroads the village schoolteacher (Meg Wynn Owen) to make a complaint claiming that Lomax assaulted her. Lomax’s only aide comes in the form of a police detective from outside the community, DCI Jenkin (Norman Jones), who warns Lomax that the locals are 'Strange people in some ways; introverted, if you know what I mean [….] Well, they're not really of the 80s: the paper mill's gone kaput, and engineering practically finished, the quarry's closed and people drifting away. The ones that are left, they're not used to visitors, strangers [….] I don't want to come back again next week and organise another search for you'.

‘The Watcher’ is a very strange, abstract episode, reminiscent of some of the episodes of the Western series Rawhide (CBS, 1959-66), which occasionally featured isolated, superstitious communities that seemed to exist outside organised society, almost as if they were towns populated by ghosts. (‘The Watcher’ has some superficial similarities with ‘The Witch’, an episode of The Fugitive in which Kimble is accused, by the members of an isolated rural community, of terrorising a young girl in the woods; in both ‘The Watcher’ and the episode of The Fugitive, a schoolteacher plays a key role in convincing the locals of the innocence of Lomax/Kimble.) Powerful and disturbing, this particular episode is reminiscent of such rural nightmares as The Wicker Man and Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1972). Like the drovers’ journey in Rawhide and Kimble’s flight from the forces of law and order in The Fugitive, Lomax’s voyage may be likened to a journey through purgatory towards redemption.

All of the episodes were written by Roger Marshall and evidence Marshall’s characteristic dry wit and ear for regional dialect. Marshall’s work is grounded in the realities of daily life and challenges stereotypes: for example, in contrast with much of British television (which depicts drug addiction as a trait of the young working-class), in Travelling Man’s first episode Lomax encounters a middle-aged, middle-class drug addict, Sally Page. The wife of an antiques dealer, Sally is a former nurse who became addicted to narcotics after using them to help her through her long shifts. It is little touches such as this that make Marshall’s work feel so modern: even though it is now over twenty-five years old, Travelling Man feels more modern and ‘in touch’ than many contemporary television dramas, especially those that deliberately try to make themselves seem ‘edgy’ and ‘authentic’. (In his challenging of stereotypes based around class and age, Marshall can perhaps be favourably compared with Jimmy McGovern.) The thirteen episodes of Travelling Man are spread over four DVDs. Episodes: Disc One: 1. 'First Leg' (51:45) 2. 'The Collector' (51:48) 3. 'The Watcher' (51:56) Disc Two: 4. ‘Grasser’ (50:42) 5. ‘Moving On’ (51:16) 6. ‘Sudden Death’ (53:21) Disc Three: 7. ‘A Token Attempt’ (52:23) 8. ‘Weekend’ (50:33) 9. ‘The Quiet Chapter’ (49:12) Disc Four: 10. ‘Hustler’ (52:02) 11. ‘On the Hook’ (52:35) 12. ‘Blow-Up’ (52:23) 13. ‘The Last Lap’ (52:35)

Video

Shot on video, Travelling Man looks excellent on this DVD set. Colours are sharp and vibrant, and the image is detailed; the episodes are in superb shape.

The episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3 and appear to be uncut; the break bumpers are present.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track. The music is a little too insistent at times, sometimes dominating the soundtrack, but that is a problem of the series’ production rather than its transfer to DVD. The music score is effective: featuring pan pipes, it has connotations of loneliness and despair. However, it is sometimes allowed to dominate the soundscape of the episodes, and is therefore occasionally something of a distraction. There are no subtitles.

Extras

None.

Overall

It has to be said that although Travelling Man touches on the issue of alienation that was so successfully mined in The Fugitive, Marshall’s scripts rarely explore Lomax’s alienation in any depth. The aforementioned episode ‘The Watcher’ is a notable exception, in its depiction of a society in which Lomax is a complete outsider, treated with suspicion by everyone he meets. Although, as noted above, on a superficial level Travelling Man may seem to be nothing more than another ‘light’ crime-themed show, there are some unsettling and challenging undercurrents bubbling underneath the surface of the show – but some episodes (for example, ‘The Collector’ and ‘The Watcher’) are more successful in highlighting these themes than others. The series is also arguably more effective when introducing self-contained narratives that ‘spin off’ from Lomax’s central quest to find his son and clear his name, than in those episodes which focus directly on Lomax’s desire to find the men who framed him for the theft of the money and therefore destroyed his life. It is a shame that there are so few episodes of Travelling Man. However, the series is a pleasant – and largely forgotten – surprise. Its transposition of the all-American open-roads-and-moral-freedom structure of The Fugitive onto the very British setting of the UK’s canal network is inspired, and Marshall’s dry wit and ability to provoke thought make this series a rewarding experience to watch. References: Etter, Jonathan, 2003: Quinn Martin, Producer. London: McFarland Schickel, Richard, 1965: ‘Everything’s Coming Up Loners: TV’s Lonely-Man Shows’. Life (12 November, 1965): 27 Skoble, Aeon J., 2008: ‘Action and Integrity in The Fugitive’. In: Sanders, Steven & Skoble, Aeon J. (eds), 2008: The Philosophy of TV Noir. University Press of Kentucky For more information, please visit Network DVD.

|

|||||

|