|

|

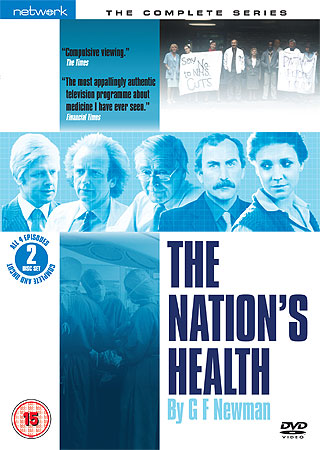

Nation's Health (The) (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th March 2010). |

|

The Show

In 1963, the French thinker Michel Foucault published The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. In the book, Foucault argued that medicine was a self-legitimating closed system whose logic and methods served to validate its conclusions. The logic of the field of medicine is rarely questioned due to the authority held by the discipline, and thus in Foucault’s eyes medicine is a self-perpetuating system of power: its conclusions (ie, its diagnoses and methods of treatment) are justified through the discourse associated with the field rather than through any objective reality. When Foucault’s book was published, the National Health Service was still a relatively new organisation, having been established in 1948. In the 1960s, the NHS was still a strong organisation, although as the decade progressed the organisation was finding itself having to deal with a period of rapid change in terms of medical technology (Greener, 2008: 84). In the 1960s and 1970s, the development of new treatments and techniques resulted in ‘new demands for services’ for illnesses that may otherwise have gone untreated: for example, ‘[d]rug therapy for people with mental illness increased in use […] offering patients with these conditions the opportunity for very different lives, free from institutions’ (ibid.). This proved costly, and throughout the 1970s and 1980s the development of new medical technologies, and the concomitant demand for new treatments, resulted in the NHS requiring increasing amounts of money; by the 1980s the NHS’s consumption of public money was increasingly questioned by both the public and the ideology of the New Right. During this decade, a number of changes were implemented from within the NHS which have continued to be controversial, including an ‘increased focus on the importance of management’ (ibid.: 37). In 1983, the year of the production and broadcast of The Nation’s Health, attempts to restructure the NHS into a more ‘business-like’ model were made through ‘the appointment of general managers in posts explicitly designated to make the NHS more business-like by giving clearly-designated individuals the responsibility for running services’ (ibid.: 60). During this period, the NHS was also placed in counterpoint to private methods of treatment, and in the 1980s private sector medicine grew substantially (ibid.: 129). However, private sector medicine is ‘perhaps best seen as offering an increasingly affluent middle class a supplement to the NHS rather than an alternative to it’, with many private patients ‘commuting’ between NHS-provided services (such as NHS GPs) and private clinics (ibid.). It is this era of change within the NHS that forms the focus of G(ordon) F(rank) Newman’s 1983 four-part docudrama The Nation’s Health. Produced by Euston Films for Thames Television, the series was broadcast on the then-new Channel 4. Each episode focused on a different issue: the first episode, ‘Acute’, focused on surgical practice; episode two, ‘Decline’, examined obstetric and gynaecological practice within the NHS; the third episode, ‘Chronic’, offered a study of the treatment of geriatric patients; and the final episode, ‘Collapse’, focused on the treatment of mentally ill patients. Newman’s series offers a bleak look at the NHS, with each episode blacker than the one that preceded it; the series suggests that the NHS is riddled with inadequate budgets, outdated practice and poor ethics. Newman’s series also offers a direct questioning of the concept of medicine, although it has to be noted that Newman is reputed to be a strong proponent of alternative medicines – something which is explored in Newman's 1994 drama The Healer (see Bedell, 1994: np).

The protagonist of the series is a newly-qualified doctor, Jesse Marvill (Vivienne Ritchie). The series follows Jesse through four different sectors of the NHS, although the episodes are not focalised entirely through Jesse: the NHS is seen from a variety of different perspectives, from doctors and patients to administrators and kitchen staff. Each episode begins with a quote, presented via an onscreen title, which is posited as a hypothesis that the episode goes on to explore. The first episode opens with the statement, ‘Objectivity and humanity cannot co-exist more than a little’; the opening quote of episode two, which in part explores the relationships between the commercially-minded pharmaceutical companies and the NHS, suggests that ‘The medical establishment prefers treatment to prevention’; episode three’s opening title asserts that ‘Health should be judged by the quality of health rather than its quantity’; and echoing another work by Michel Foucault, the 1961 study of mental illness Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, the final episode declares that ‘Mental hospitals are an institution whose primary function isn’t to cure the sick but to defend a society based on privilege and injustice’.

In the first episode, ‘Acute’, Jesse finds herself the object of surprise when she applies for a surgical position at St Clair’s hospital: 'There's a stamina needed for an eight hour session in theatre that's often peculiarly masculine', one of the (male) interviewers chauvinistically tells her. After she has secured her place, Jesse discovers yet more chauvinism and prejudice. She is warned by a male colleague that ‘The old man won't like seeing you in jeans on the ward: he's a leg man'. Scorn and derision is not reserved for women: although the hospital is in dire need of a new surgical registrar, the chief surgeon (Trevor Bowen) is unwilling to accept a Nigerian registrar, asserting to his secretary that ‘I told them once that black isn’t acceptable’ and, later, telling her 'I'm fed up of talking about it. There is no fucking way that I'm accepting a spear-throwing fucking wallah as a local registrar'. Leaving aside the dominance of white middle-class males within the hospital, Jesse finds the world of medicine disorganized, riddled with politicking and seemingly more concerned with budgets than with the care of patients. The kitchens are in disarray; painters are working in the kitchens whilst cooks are preparing the food, flakes of paint falling into the pans. The painters are working during the daytime because the hospital management considers their rates for working at night, when the kitchens are empty, to be too expensive. Porters discuss a man who was entered for an operation and had the wrong lung removed. Doctors seem unable to cope with the stress experienced by their patients’ families: when Ray Taylor (Tony Calvin) is admitted and diagnosed with throat cancer, the news is delivered to Mrs Taylor (Eileen O’Brien) in the office of Thompson, the chief of surgery. Mrs Taylor breaks down, sobbing uncontrollably; Thompson simply looks uncomfortable, unsympathetic to Mrs Taylor’s experience and seemingly unwilling to attempt to console her. The doctors themselves are suffering from poor working hours and, led by Vernon Davis (Ian McDiarmid), they put together a petition for better working hours. Jesse is suckered into presenting the petition, and her supervisor tells her that Davis and his associates are a ‘rotten crowd’, reminding Jesse that medicine is a vocation: ‘It’s a way of life, Jesse. You don't do the job for the conditions of service. I think you have to accept the rotten hours and the pressures on relationships and marriages that they bring'. Davis brings forward a complaint against a consultant, Smith-Sampson (Richard Leech), claiming that ‘some of his procedures aren’t in the best interests of the patients’. Senior staff band together against Davis, leading to Davis being labeled by Smith-Sampson as a trouble-maker due to his ‘medico-politicking’. Davis’ seemingly-legitimated complaint (about a case which led to the death of a patient) is discussed by the consultants and management during an informal meal, and Davis’ claims about Smith-Sampson are dismissed as the ramblings of a rabblerouser who is ‘obsessed by the idea of management and consultants conspiring against the junior doctors’.

An ongoing narrative is established in this first episode. The Nightingale block is to be closed down in order that the hospital can find the money within its limited budget to amend the problems caused by an outbreak of food poisoning (which may or may not be related to the painting taking place in the kitchen). Management propose closing the Nightingale block by pretending that it has simply been closed temporarily ‘for upgrading’. By the end of the series, despite concern from patients, staff and the local council, the Nightingale block (which houses the majority of the hospital’s geriatric patients) is earmarked for sale to a private clinic. Jesse’s attempts to empathise with her patients are placed in juxtaposition with the principles of modern medicine. When Thompson proposes a radical surgery on Mr Taylor, which will remove half of his face (including part of his upper and lower jaws and part of his tongue and throat), Jesse reminds Thompson that the procedure will have a severe impact on Mr Taylor’s quality of life. Jesse suggests that they should allow Mr Taylor to make an informed decision, which may mean letting the disease run its course; Thompson reminds her that ‘We mustn’t be tempted to play God. Let’s just get on with the job’. After the surgery, Jesse speaks with her mentor, asking why Thompson did not allow Taylor to select whether to submit to the surgery or let the disease run its course, she is told that ‘Patients are probably better off with simple options, Jesse’. In the second episode, ‘Decline’, we are shown something of the relationship between private health care and the NHS, and between the NHS and pharmaceutical companies. Jesse is studying under a gynaecologist, Dr Montagu (Julian Fox). Montagu admits to one patient that due to a lack of beds, patients defined as non-urgent will continually be pushed to the back of the queue and can face an indeterminate wait. However, if the woman were a private patient she could be seen before the end of the week. Later, one of the nurses tells Jesse that Montagu only appears on the ward when he is to ‘deliver a private baby himself’. Meanwhile, a parallel narrative is introduced; focusing on the work of an overworked elderly GP, Dr Thurson (Sebastian Shaw), it highlights the ways in which pharmaceutical companies exploit the NHS. Thurson is visited at his surgery by a representative from a pharmaceutical company, who essentially blackmails Thurson into prescribing an experimental drug to his patients: Thurson is told that if he can administer the drug to five patients, he will receive either a £75 cash fee or a handsome carriage clock. In a later scene, Davis complains to a representative from a drug company that the pharmaceutical companies only aim to 'Treat the symptom, encourage the cause'; Davis pointedly tells the man, 'You have a nice, cosy arrangement for testing drugs with certain consultants'. Later, in the next episode, St Clair’s will be approached by a representative from an American drug company who proposes using the hospital’s geriatric patients as guinea pigs in the testing of a new cancer drug; the drug has already been tested in the US on prisoners. A member of the hospital board asks, ‘Are patients expected to give their consent’. The American visitor acknowledges, ‘Yes, those aware of time and place’. The plan is turned down by the ethics committee, but one of the hospital’s members of management offers to find the American drug company some patients: he makes it clear that he is willing to override the ethics committee. ‘I think we’ve made the wrong decisions for the wrong reasons’, he tells the American representative: ‘It would be simpler if we used patients who have no family’.

Perhaps most traumatically, we are shown a birthing from the perspective of the mother (Angela Warren). Isolated from her husband (in a scene that seems anachronistic today, when it is common for a baby’s father to be in the birthing room), the mother is excluded from the doctors’ and nurses’ routines, which appear to be a closed secret. Immediately after the birth, they are huddled in the corner of the room, weighing the baby as the mother asks 'Can I hold my baby now? [….] What's wrong with my baby? There's something wrong with her [….] Why can't I hold my baby, doctor?' The mother’s exclusion from what the doctors and nurses are doing, and her separation from her new child, is reinforced through the way in which the scene is shot: we are shown, from the mother’s perspective, nothing but the backs of the medical professionals, who are on the other side of the room. In subsequent scenes, the mother is shown struggling to bond with her new baby (and suffering with what would now most likely be labeled postnatal depression), who has been removed from her immediately after birth and taken away by the medical staff before being subjected to tests. The woman also fails to bond with her husband. The third and fourth episodes become increasingly bleak, with the third episode focusing on the closure of Nightingale block, which will save the health authority £560,000 (one-twentieth of the hospital’s expenditure) at the expense of 120 beds (on quarter of the hospital’s total number of beds). Closing Nightingale block, which houses the majority of the hospital’s long-stay geriatric beds, will result in most of the hospital’s geriatric patients being treated as outpatients. As one of the attendees at a public hearing asserts, ‘There are many old people who are at risk at home and should be brought into hospital. Unless beds can be made available for this type of patient, the Health Authority is failing to meet the requirements of the 1965 Health Act'. However, it is revealed that the hospital plans to sell the Nightingale block to be converted into a private clinic. One of the members of the hospital’s management acknowledges the growth of private medicine that took place throughout the 1980s, asserting that 'Private enterprise has to be seen to meet the shortfall of public sector medicine. If we get our timing right, we'll be seen to meet a real need'. The fourth episode confronts the issue of the treatment of mentally ill patients and is perhaps the most overtly troubling: in one scene, a nurse is shown force-feeding a mentally ill patient whilst aggressively shouting ‘Open it [the patient’s mouth], you stupid woman’. (Some aspects of this particular episode are comparable with Frederick Wiseman’s controversial 1967 documentary Titicut Follies, a disturbing film which focused on the treatment of inmates in Massachussetts Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane.)

By the time of the production of The Nation’s Health in 1983, G F Newman had already undertaken a Foucauldian critique of the police and the judicial process, via the 1978 BBC series Law and Order, a four part mini-series which told the same story of London thief Jack Lynn (Peter Dean) from four different perspective: the detective who arrests Dean (‘The Detective’s Tale’), Lynn himself (‘The Villain’s Tale’), the solicitor who is hired to represent Lynn (‘The Brief’s Tale’) and, finally, Lynn’s experiences in prison (‘The Prisoner’s Tale’). Adapted from a trilogy of novels written by G F Newman, Law and Order was criticised by both the police and the Prison Officers Association for its suggestion that corruption was endemic throughout the police and the prison service (see Clark, 2003: np). The series’ naturalistic representation of its subject matter was seen as problematic, in that Law and Order presented itself as a docudrama, using the visual techniques associated with documentary filmmaking (see Newman, 2009: np). In preparation for writing The Nation’s Health, Newman reputedly conducted much in-depth research into the functioning of the NHS, spending time ‘undercover’ in hospitals and amongst patients and staff. Newman’s research is evidenced throughout all four episodes: the series has a strong sense of authenticity in its writing, from the emphasis on internal politics to more subtle details (such as Montagu’s insistence, in the second episode, on referring to a woman’s womb as ‘the (little) box’). In a 1994 interview with Newman for The Independent, Geraldine Bedell asserted that ‘In The Nation’s Health, Newman expressed more directly his conviction that “in the average general hospital, one- third of people are suffering from illnesses induced by the medical profession”’ (Newman, quoted in Bedell, 1994: np).

The series is frequently polemical; and, despite Newman’s characteristically strong research and writing, sometimes Newman’s authorial voice seems to intrude into the drama and awkwardly use the characters as mouthpieces for Newman’s own strong beliefs – chiefly his interest in alternative medicines. (These strong assertions no doubt provided much material for discussion in the live studio debates that followed the original broadcast of each episode.) In the first episode, Jesse is introduced to Laurence James (Karl Francis), a fellow doctor who is dismissed by Jesse’s mentor as ‘a bit of a nutter’ for his promotion of alternative therapies. Discussing Jesse’s patient, Mr Taylor, James tells Jesse - in the series' most explicitly Foucauldian monologue - that 'Perhaps your Mr Taylor doesn't want to be helped. Some people cling to illness [….] Going into hospital has become an inevitable process which most of us don't question. Often, it reinforces the need to be ill [….] Medicine is getting a bit bogged down in empirical investigation. Medicine is not a precise science. Most of what we practice works as a result of the ritual of the laying on of hands. A lot of doctors have lost the gift of healing, or don't even consider it [….] It's easier not to acknowledge it, but to intellectualise instead and rely on technology and pharmacology'. Later, Jesse proposes to Mrs Taylor that her husband should perhaps see a healer. Mrs Taylor is surprised at the suggestion that she should consider a 'faith healer'. Jesse reminds Mrs Taylor that 'Consulting a doctor is in its own way an act of faith'. In the third episode, in another example of a scene in which Newman’s authorial voice seems to intrude on the drama, one of the visitors to the meeting about the closure of Nightingale block asserts that 'There is a strong economic argument for homeopathic medicine'. However, this intrusion of Newman’s authorial voice is characteristic of the writer’s work, and Newman once stated that ‘Drama is about stretching cosy assumptions to breaking point and finding something worthwhile with which to replace them’ (G F Newman, quoted in Clark, 2003: np). However, in his commentary on The Nation’s Health for the BFI’s ScreenOnline website, Anthony Clark states that ‘Whether The Nation’s Health achieved this is debatable - the four episodes largely reinforced a widely-held view of the time that the NHS was on the brink of collapse, and Newman clearly fails to suggest anything 'worthwhile' as a solution to this despondency’ (Clark, 2003: np). One of the conventions of television docudramas is that they present their narratives with little of the niceties associated with more conventional television dramas. Characters wander onto the screen with little or no introduction, and the viewer is often thrown into the midst of events without the aid of a conventional narrative structure. This can be confusing for viewers, and The Nation’s Health exhibits a number of these traits. The first episode is overwhelming in its introduction of a plethora of characters who are not introduced and named for the audience; this contributes to the sense of chaos and disorder engendered in the episode, which the programme suggests is endemic within the NHS, and posits the viewer in the shoes of the programme's protagonist Jesse Marvill. However, despite its occasionally polemical approach to its subject matter and its sometimes confusing structure, The Nation’s Health is a joy to watch: Newman’s thorough research is evident throughout, and there is an easy naturalism to the characters and dialogue. The series is also thoroughly thought-provoking, and despite some changes within the NHS (most notably on an aesthetic level: most of the old high-ceilinged Victorian hospitals have since been closed and replaced with more modern buildings) many of the issues are as pertinent now as they were in 1983. Episodes: Disc One: 1. 'Acute' (85:23) 2. 'Decline' (84:47) Disc Two: 3. 'Chronic' (81:39) 4. 'Collapse' (83:00)

Video

Shot on 16mm film, The Nation’s Health has a documentary-style aesthetic that is highlighted from the opening shot of the first episode, a handheld reverse tracking shot following Jesse’s progress through St Clair’s. The series is presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3 and does not appear to suffer from any edits. There is intermittent film damage throughout the four episodes, but this serves to consolidate the documentary aesthetic of the series.

Audio

The two-channel mono track is effective. However, The series’ naturalistic use of sound, complete with overlapping dialogue, can mean that sometimes lines are lost or drowned out by ambient sound. Unfortunately, there are no subtitles, but by and large the majority of the dialogue is audible.

Extras

On its original broadcast on Channel 4 in 1983, each episode of The Nation’s Health was followed by a live studio discussion examining the issues raised in the programme. It is a shame those studio discussions are not included in this set, as they would have helped to contextualise the series.

Overall

A powerful drama that is in marked contrast to most of the medical-themed dramas on modern television (and, more pointedly, today’s docudramas), The Nation’s Health is a challenging, thought-provoking mini-series. Newman’s approach may be too polemical for some, but Newman’s work as a writer is issue-led and there is no denying the amount of research evident in this series. Each episode succeeds in presenting a complex analysis of a specific aspect of the NHS, and although the series is anachronistic in some ways (for example, in the Victorian architecture of St Clair’s) many of the issues (the relationship between pharmaceutical companies and the medical profession; the treatment of elderly patients) are still pertinent today. This DVD release of The Nation’s Health is extremely welcome, and makes an ideal accompaniment to the BBC’s 2008 DVD release of Newman’s earlier series Law and Order. The only criticism that could be made of this release is the lack of any contextualisation of the series, either in relation to the issues it presents or in relation to Newman’s work in general. References: Bedell, Geraldine, 1994: ‘”Carnivores enjoy the same pleasure as child murderers”: G F Newman speaks’. The Independent (30 January 1994): en Clark, Anthony, 2003: ‘The Nation’s Health’. ScreenOnline. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/481759/ Greener, Ian, 2008: Healthcare in the UK: Understanding Continuity and Change. London: The Policy Press Newman, G F, 2009: ‘Good Cop, Bad Cop’. BBC News Magazine. [Online.] http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/7971731.stm For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|