|

|

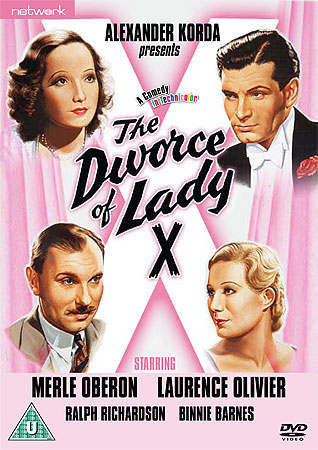

Divorce of Lady X (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th April 2010). |

|

The Film

Intended as a vehicle for Merle Oberon, to mark her return to Britain after several years spent making films in Hollywood, The Divorce of Lady X (Tim Whelan, 1937) was designed as a ‘glamorous production’ with the intention to capitalise on Oberon’s newly-acquired status as ‘a top international star’ (Low, 1997: 223). Produced by Alexander Korda, The Divorce of Lady X was in fact a remake of an earlier Korda picture, Counsel’s Opinion (1933). The Divorce of Lady X was also the first Korda-produced film to be shot in Technicolor; it was only the second British Technicolor film to be released (following Harold D. Schuster’s Wings of the Morning, released earlier the same year). That The Divorce of Lady X was one of the earliest British pictures to be shot in the Technicolor process is fairly remarkable, considering the film’s basis in a play (Gilbert Wakefield’s Counsel’s Opinion) and its ‘stagey’, studio-bound aesthetic: in The Age of the Dream Palace (1984), Jeffery Richards asserts that the film was ‘photographed in exquisite but unnecessary Technicolor’ (166; see also Sutton, 2000: 213). The film concerns Everard Logan (Laurence Olivier), a divorce barrister who is forced to spend the night in the Royal Parks Hotel after a pea soup fog (‘Long time since we ‘ad one of them’, notes a bobby) prevents him from travelling home. The same night, a fancy dress ball is taking place in the hotel’s ballroom; the guests, including Leslie (Merle Oberon), are advised to stay at the hotel. However, as the hotel is full the attendees of the ball are directed into sharing suites with the hotel’s guests. The hotel manager asks Logan to give up his two-room suite so that a group of women may sleep in it, but Logan adamantly refuses ('I'm very cross and very tired; in fact, quite wild with fatigue. But I'm the legal possessor of this suite, and I'm determined to defend it with every power in my possession [….] What I really need is a good night's sleep, and I shall have that, though every lady in London thinks me a cad, a brute and a beast'). However, after the manager has left, Leslie sneaks into Logan’s room; she pleads with Logan, who christens her ‘Lady X’, to let her stay in his suite, and tries to persuade him to sleep on the sofa ('Of all the shameless impudence. Was there anything ever more female? And you actually thought you could get away with it', Logan asserts). Eventually, Leslie manages to trick Logan into sleeping on the floor of the suite’s living room, whilst she sleeps comfortably in the bedroom. Over breakfast, Logan and Leslie flirt, and after Leslie leaves Logan realises that he has begun to fall in love with her. However, Leslie was wearing a ring and Logan believes that she is already married. Later, Lord Mere (Ralph Richardson) approaches Logan, believing his wife, Lady Mere (Binnie Barnes), to be conducting an affair. Due to a mix-up, Logan believes Leslie to be Lady Mere, and begins to worry that he may be named as a co-respondent in the divorce of Lord and Lady Mere. Aware of Logan’s confusion, Leslie continues to romance Logan, teasing him by letting him believe that she is Lady Mere and that she has already had four husbands – in an effort to teach the chauvinistic Logan a lesson.

A light romantic comedy, The Divorce of Lady X sees Olivier invest himself in the character of Logan, a chauvinist whose attitudes towards women are delineated in his refusal to give up his hotel suite and his later fiery assertion, in divorce court, that ‘Woman has a religion of her own. The ancient creed of womanhood. It contains only one article of faith […] and that is that she is the unique and perfect achievement of the human species, being especially evolved to be above criticism, beyond reproach and outside the law [….] Modern womanhood […] demands freedom but won’t accept responsibility [….] By “independence”, she means idleness; by “equality”, she means carrying on like Catherine the Great’. It is this particular assertion, witnessed by Leslie, that encourages Leslie to try to educate Logan about women. Leslie’s scheme involves creating a fictional identity for herself, which plays into Logan’s prejudices about women, that inspires both fascination and anxiety in Logan. As such, the film explores the same kinds of issues relating to sexual politics that were at the heart of contemporaneous American screwball comedies such as Mr Deeds Goes to Town (Frank Capra, 1936) and Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938).

However, the film’s climax, in which Logan learns of Leslie’s true identity, proposes to her and proclaims marriage to be one of society’s greatest institutions, seems to come a little out of left-field; it is hard to believe that Logan’s bitter, indignant misogyny can be so easily overcome. As Geoffrey Macnab notes in Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screen Acting in British Cinema (2000), Olivier plays Logan ‘with precisely the same scowling disdain that James Mason brought a few years later to his aristocratic sadists in Gainsborough melodramas’ (142). Macnab suggests that the bitterness in Olivier’s performance may have been due to the disdain he held for his work for Korda and his ‘impatience with his roles’, which is ‘often apparent’ in the films he made during this period (ibid.: 141). The film runs for 87:29 mins (PAL) and does not seem to suffer from any cuts.

Video

The film is presented in its original Academy screen ratio of 4:3. Some of the framing seems very tight, but there is no direct evidence of cropping.

The Technicolor image is well-presented. The colours are strong and vibrant, although as noted above the film has a very ‘stagey’, studio-bound look – despite some atmospheric opening shots of London enveloped in the pea soup fog that acts as a catalyst for the narrative.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track. This is clear throughout, although there is an intermittent background ‘hiss’ on the soundtrack – most likely due to the age of the material.

Extras

The sole extra feature is an image gallery (1:52).

Overall

A light and frothy, but arguably overproduced, romantic comedy with what, on the surface at least, seems to be an interesting subversion of gender roles – with Merle Oberon’s Leslie taking an active role and attempting to chip away at Olivier’s character’s chauvinism, The Divorce of Lady X is ultimately entertaining but not particularly memorable. Logan’s epiphany at the end of the picture is dictated by the conventions of romantic comedies but it unconvincing, considering the strength with which he makes his chauvinistic assertions earlier in the narrative. Olivier’s performance is good, but this was a period in which he had little investment in cinema: he once claimed that Korda ‘gave me opportunities which I took disdainfully because I still despised the medium’ of cinema (Olivier, quoted in Macnab, op cit.: 141). Oberon seems to have more investment in the material, but the role of Leslie is arguably more reactionary than it may at first glance seem, embodying the ‘female “doubleness”’ found in many of Korda’s other films: Oberon’s Leslie is both virginal and manipulative (Harper, 2000: 12). David R. Sutton notes that the film’s ‘handling of comedy’ is ‘ponderous and heavy-handed […] swamped by the very production values [Korda] brought to bear on it’; for Sutton, the film has ‘a feeling that what had begun life as a modest “quota-quickie” has been rather overdressed in the interests of a spurious idea of “quality”’, characteristic of Korda’s ‘tendency […] to pass off a piece of fluff as “sophisticated” and “glamorous” entertainment’ (op cit.: 216). References: Harper, Sue, 2000: Women in British Cinema: Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know. London: Continuum Publishing Group Low, Rachael, 1997: The History of British Film, Volume VII: The History of British Film 1929-1939: Film Making in 1930s Britain. London: Routledge Macnab, Geoffrey, 2000: Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screen Acting in British Cinema. London: Continuum Publishing Group Richards, Jeffery, 1984: The Age of the Dream Palace: Cinema and Society in Britain, 1930-1939. London: Routledge Sutton, David R., 2000: A Chorus of Raspberries: British Film Comedy, 1929-1939. Quebec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|