|

|

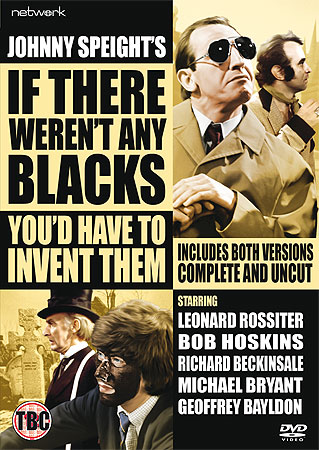

If There Weren't Any Blacks You'd Have to Invent Them

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th April 2010). |

|

The Show

Originally written for the stage (and first performed in 1965), If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them offers a view on some of the abiding themes of comedy writer Johnny Speight’s work: principally, racial prejudice, scapegoating and a satirical critique of both the political left and the political right. Written before the development of Speight’s most famous creation, the television sitcom Till Death Us Do Part (BBC, 1966-74), If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them was filmed for television in 1968, and again in 1974. (Both versions were made for London Weekend Television.) Aside from some of the major themes of Speight’s comic output, If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them also offers a version of the most recognisable character type from Speight’s other work. The Workman (played in the 1968 version by Peter Craze, and in the 1974 version by Bob Hoskins), in his ranting against the upper classes and his semi-informed critique of the class system, channels one of Speight’s earliest creations for television: the belligerent tramp in The Arthur Haynes Show (ATV, 1957-66), who angrily (and comically) railed against the class system. The character of the Workman also looks towards Speight’s ‘angry old man’ Alf Garnett (Warren Mitchell) in Till Death Us Do Part, a logical extension of the tramp character that Speight created for Haynes – Garnett’s ire was directed not against the class system but channelled through chauvinism, racial prejudice, misogyny and homophobia – and Garnett’s layabout son-in-law Mike (Anthony Booth), who used half-digested socialist rhetoric to justify his workshy nature. Openly allegorical, If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them takes place in a cemetery in which a variety of nameless characters (designated only as ‘The Workman’, ‘The Blind Man’, ‘The Young Man’, etc), symbolic of various social attitudes, gather. The cemetery is a non-place, an abstract environment; this, combined with the allegorical nature of the play, its emphasis on ritual and the archetypal characters, suggests that Speight may have been influenced by the Theatre of the Absurd (eg, Samuel Beckett’s 1953 play ‘Waiting for Godot’). The play confronts themes of scapegoating and prejudice; the structure is episodic but develops into a narrative towards the end of the play, when the various diverse characters begin to come together, united (for various reasons) in their prejudice and their need to find a scapegoat. It opens with the Workman, the only character to break the ‘fourth wall’ and address the audience directly (acting as a Greek chorus at various points), who in the opening sequence describes himself as ‘muggins, a bloody dogsbody’ as he pulls on a church bell-rope during a funeral.

Elsewhere in the cemetery, a bowler-hatted man – the Officer (Moray Watson/Lewis Fiander) – pulls out a revolver and holds it at a young mourner, the Private (Leonard Cracknell/John Nightingale). The Officer claims ‘I’ve been waiting for you [….] Well, not exactly you, but someone like you, someone your size'. He tells the young man to get undressed: 'I'm a fair minded man, but I'm also a disciplinarian'. The two men go behind a vault to get undressed, re-emerging in military uniforms. The Officer marches the Private around the cemetery, all the while holding the revolver to the younger man's head.

In another part of the cemetery, the Blind Man (Leslie Sands/Leonard Rossiter) enters with the Backwards Man (Jimmy Hanley/Donald Gee), who walks backwards – holding on to the Blind Man – and with his eyes closed. 'Always shutting your eyes. Anything you don't like, anything you're afraid to look at, you shut your eyes', the Blind Man tells the Backwards Man good-naturedly. 'Well, that's what eyes are for. That's why eyes were made to close. We should use all our faculties. There's no point having shutters on your eyes if you don't use them', the Backwards Man responds.

The Blind Man and the Backwards Man sit on a bench, and they are soon joined by a prissy, slightly camp young man – credited simply as the Young Man (John Castle/Richard Beckinsale). The Young Man makes allusions to negative stereotypes associated with gay culture: cottaging, an overbearing mother, ill-defined ‘dirty habits’, bed-wetting problems, cross-dressing. 'You're not kinky, I suppose, are you, you and your friend?' the Young Man asks the two other men, apparently hoping that they are. It doesn’t take long for the Blind Man to decide that there the Young Man is an ‘other’ of some kind. 'You're not coloured, are you?' the Blind Man questions the young man aggressively, after the young man talks about the issue of equality. 'But I'm white, as white as you are', the Young Man asserts. The Blind Man responds by declaring that nobody is whiter than him; 'Very liberal, you are. One of these damned equalisers', he tells the Young Man: 'I tell you I'm whiter than you, much whiter. And what's more, I'm blind, and you're not, and that makes me different – much, much different to you'. The Blind Man turns to the Backwards Man and tells him, 'I'm sure he's coloured. He's black, I knew it. I knew it the minute he sat down. I sensed it'. 'I'm not black. I might wear women's clothes occasionally and have dirty habits, but I'm not black. That's one thing I'm not', the Young Man asserts angrily.

Walking away, the Young Man shouts at the Blind Man: 'You're black. You're the one that's black, and if you had eyes you'd see it'. The Blind Man laughs, but then he turns to the Backwards Man and asks him, 'I'm not black, am I? I'm not'. The Blind Man panics and begins to doubt himself, seeking reassurance: 'Tell me. He's telling lies, isn't he. I'm purest white, now tell me I am', he begs his friend. 'I can't be. I mustn't be. I must be white', the Blind Man claims. However, the Backwards Man refuses to open his eyes and look at his friend, telling the Blind Man simply, 'When your beliefs are challenged, just close your eyes and have faith [….] It makes us so much more equal [….] Me, with my eyes shut, I'm just as blind as you are'. 'You and your bloody equality', the Blind Man asserts, 'why can't you let me be different?'

Desperate to prove that the Young Man is an ethnic ‘other’, the Blind Man grasps at straws in order to prove his case that the Young Man was indeed black: 'I touched his skin; it felt different. It had larger pores, too large for a white skin', the Blind Man asserts about the Young Man, inventing pseudo-scientific reasons why the young man must have been black. The Young Man approaches a chauvinistic doctor (Derek Godfrey/Michael Bryant), who has set up practice in the cemetery with a number of glamorous ‘dolly bird’ nurses (including Valerie Leon, in the 1968 version, and Vicki Michelle, in the 1974 version). The Young Man asks the doctor for help with his ‘bad habits’. Unable to help the Young Man, the doctor soon turns his attention to a young woman (Nerys Hughes/Pam Scotcher) who happens to be passing through the cemetery. He offers to replace the young woman’s legs with ‘mechanical disease-free ones that won’t wear out’, available on the NHS. The young woman protests but is soon persuaded to accept the doctor’s proposition when one of the doctor’s glamorous nurses shows the young woman her own mechanical legs. The Young Man becomes involved in a heated discussion with the Workman. Hearing the Young Man’s voice, the Blind Man resumes his attack on the Young Man, this time even more aggressively and using stronger language. 'You back again, Sambo?', the Blind Man declares spitefully. The young man protests that he's white. 'I prefer to think of you as black. Shiny, cold black', the Blind Man asserts. The Young Man becomes concerned, but the Workman reminds him, 'What does it matter what he thinks?' However, the young man is desperate to prove that he is not black: 'But he thinks I'm black, and I don't want to be black to anyone. If he thinks I'm black, then black I become, don't I'.

Responding to the Young Man’s protestations, the Blind Man asserts, 'Marvelous, isn't it, the bloody rights these people want. Show them a bit of kindness, and the next thing you know they're demanding it. Isn't it bloody marvelous, eh? If he can't be white like me, he wants me to be black like him. They don't know when to stop, these underdogs: they're bloody equality mad'. He finally resorts to threatening the Young Man: 'You're due for a beating lad; it's high time you were beaten', the Blind Man says, thrashing his white stick about. The Young Man turns to the Officer for help. The Blind Man approaches and, reading the officer with his hands, discovers that the Officer is holding a revolver. 'That's what young Sambo here needs, a gun at his head. You put a gun at his head, he might start behaving more like a black to me', the Blind Man asserts, nodding towards the Young Man. 'I need a black', the Blind Man tells the officer: 'I'm white, you see, purest white. There's no joy being white if there's no black, is there?' When the Young Man claims that the Blind Man should listen to his voice because ‘There’s no black in my voice’, the Blind Man bitterly asserts, ‘Just listen to it, eh! An educated black. A well-schooled coon’. The Blind Man sees the Young Man as an enemy, an ‘other’, because he believes the Young Man to be black. Meanwhile, the Workman, who has a chip on his shoulder about the upper classes, begins to see the Young Man as a class enemy; responding to the Young Man’s claims about his voice, the Workman says, ‘Sounds like a bit of a governor to me. He’s got a touch of the governor in him’. The Officer puts the gun to the Young Man's head. The Blind Man asks the Officer about The Private: 'He won't turn, will he? Now that he's not got a gun at his head'. The Officer replies that 'He's had a gun at his head so long that he won't notice that it's been taken away'. The Officer commands the Private to 'black up' the Young Man. The Private applies boot polish to the face of the Young Man, in a twisted parody of minstrel ‘blackface’. Recognising that despite their differences, the Private and the Young Man are united in their powerlessness, the Officer asserts that 'These blacks are very good at blacking each other'.

The voice of rationalism, the doctor reminds the others that ‘colour is just a pigmentation of the skin’. However, the Blind Man refuses to listen to reason: ‘Don’t anybody listen to him: he’s got excuses for everything’, he protests; ‘All I can say is if God had wanted the blacks to be white, He'd have made them white in the first place'. The Blind Man proposes killing the Yound Man. 'It'll help the doctor there too: he's a liberal. And if we put an end to the black, that puts an end to the colour bar', the Blind Man declares. The Young Man turns to the doctor for help, but the doctor once again refuses to offer him any support: 'What's the difference between pigmentation and boot polish? They've chosen you to play the coon. You have to let them kill you tonight, so that we who are decent can revile their crime against you', the doctor tells the Young Man. The inhabitants of the cemetery hold a kangaroo court; the Young Man is tried and executed. As the above synopsis might suggest, the characters are little more than archetypes, representative of various social attitudes. The Blind Man acts as an opinion leader, the loud voice of prejudice that turns the other members of the group against the Young Man. Although If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them was written for the stage in 1965, its television broadcast in August of 1968 came just four months after Enoch Powell’s infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ anti-immigration speech (on 20 April, 1968); in light of this, it is hard not to see the Blind Man, with his stirring of racial hatred and his desire to find a social scapegoat, as a satirical skewering of Powell’s ideas – more likely a case of happy serendipity (or clever adaptation) than intent on the part of Speight, considering how old the play was before it was televised. (However, it is altogether possible that Speight redrafted the play for this television version.) Interestingly, and as an aside, in an attempt to assert that he was a ‘man of the [political] centre’ rather than a ‘man of the right’, in an interview with Guardian journalist Martin Walker the British fascist Oswald Moseley once dismissed Enoch Powell by comparing Powell with Speight’s most famous creation, referring to Powell as ‘a middle class Alf Garnett’ (Moseley, quoted in Walker, 1977: 110). In the Guardian’s obituary of Enoch Powell, Norman Shrapnel and Mike Phillips (2001) asserted that ‘Johnny Speight’s bigoted Alf Garnett, on TV every week, offered him [Enoch Powell] up in a domesticated package and gave him a renewed currency (np). In If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them, 'black' becomes synonymous with powerlessness and social marginalisation. All of the characters are desperate to find their 'other': the Blind Man tells the Officer 'I need a black: I'm white, you see, purest white. There's no joy being white if there's no black, is there?' The Blind Man, and the other characters, need a powerless 'other' against which to define their identity. The Officer has his Private (and recruits him in a twisted parody of conscription), the Workman rails against the upper-classes and 'the governor' (where the Blind Man sees the Young Man as 'black', the Workman asserts that the Young Man sounds like 'he's got a touch of the governor in him'), and the Blind Man is so desperate to find a scapegoat that he constructs the Young Man as a racial 'other', a 'black' – the perceived difference between them justifying, for the Blind Man and eventually for the other members of the cemetery, the persecution of the Young Man..In their desperation to construct the Young Man as an 'other', the other characters ignore all evidence otherwise: when the Backwards Man notes that the Young Man 'sounds more, sort of, middle class English', the Blind Man angrily asserts, 'So that's their bloody game is it? Learning to speak middle class English, hoping it'll hide their colour, eh?' Later, the Blind Man and the other members of the group choose to ignore the doctor's assertion that ethnic difference is nothing more than 'a pigmentation of the skin'. (In response to this, the Blind Man declares, ‘Don’t anybody listen to him: he’s got excuses for everything'.) As in Till Death Us Do Part, where the apparently liberal Mike offered challenge to Alf Garnett's prejudices but was undercut by his lazy nature and his irresponsibility, none of the liberal characters in If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them are able (or completely willing) to effectively challenge the scapegoating and prejudice that take place in the cemetery. The Backwards Man chooses willed ignorance (symbolised in his willful blindness): as he tells the Blind Man, in justification of keeping his eyes closed, 'When you're in the company of a blind man, one has to be blind; it's their only chance of survival. What's the point of me seeing things you can't see: if we're too different we can't get on'. In his desire to 'get on' with the Blind Man, the Backwards Man simply reaffirms the Blind Man's prejudices, enabling his persecution of the man that the Blind Man sees as his 'other'. (The 1968 version contains an interestingly-composed shot of the Blind Man and the Backwards Man, their heads back-to-back; the framing seems to allude to the two-faced God Janus, suggesting that the Blind Man and the Backwards Man are flipsides of the same coin.) By the end of the play, even the doctor, who initially makes an attempt to challenge the persecution of the Young Man through an appeal to reason, acknowledges and enables the persecution of the Young Man, allowing it to go ahead so that he can construct his own 'other': those who have persecuted the Young Man. As the doctor tells the Young Man towards the end of the play, 'You have to let them kill you tonight, so that we who are decent can revile their crime against you'. There is very little difference between the 1968 version and the 1974 adaptation: the script of both versions is essentially the same, with some minor changes in the dialogue. The differences lie in the staging, set design and the performances. The 1974 version has a more abstract setting: the cemetery in the 1968 version roughly approximates a real cemetery, whereas the cemetery in the 1974 adaptation is more like a visualisation of one of the scenarios from J. G. Ballard's The Atrocity Exhibition, being littered with half-destroyed cars and statues with neon signs hanging from them. In terms of staging and performances, the 1974 version hedges towards farce: Beckinsale ups the ante in terms of the effeminate characterisation of the Young Man, and Rossiter invests the Blind Man with the same sweaty, hysterical panic that the great comic actor brought to his role as Rigsby in Rising Damp (Yorkshire Television, 1974-8). The hysteria within Rossiter's characterisation of the Blind Man is very different from the bitter, venomous hatred that Leslie Sands' Blind Man barely tries to conceal (in the 1968 version). Rossiter's Blind Man seems very much of the 1970s, an era in which sitcoms confronted the issue of prejudice – but the prejudiced characters (such as Rigsby) tended to be comically undercut by their panic, their outbursts of anger deflated by their blustering hysteria about race, sexuality and other indices of 'difference'. Conversely, Sands' bitter Blind Man seems the product of a different era, carrying some of the venom of Warren Mitchell's performance as Alf Garnett in Till Death Us Do Part: unlike Rossiter's Blind Man and like Mitchell's Alf Garnett, Sands' Blind Man is thoroughly certain of himself, his outbursts of prejudice filled with genuine bile, and he is therefore more convincingly 'dangerous'. The lighter, more farcical tone of the 1974 version is signified immediately, through the use of a comedic jazz-inflected trumpet tune to underscore the opening sequences. Furthermore, more visual comedy is introduced in the 1974 version: Bob Hoskins' Workman, oddly reconfigured as a Teddy Boy, pulls on a bellrope that seems to be suspended from the sky, and which transports him across the set. Other changes in the 1974 version include a new conversation between the Workman and a funeral director, with the Workman asserting, after a funeral, that 'That's what I always say about it, death: it's a good living [….] Makes men brothers'. The 1968 version is arguably more effective and, in the context of its original broadcast not long after Enoch Powell's infamous and era-defining 'Rivers of Blood' speech (references to which recur throughout much of Speight's later work), more timely: the shot composition is more careful (as in the framing of the Blind Man and the Backwards Man, each facing in a different direction like the two faces of Janus), and some of the changes to the 1974 version are perhaps a little mishandled or out of place. (After he has been 'blacked up', Beckinsale delivers a redundant and slightly forced allusion to Al Jolson's minstrel 'blackface' character, declaring 'Mammy' and spreading his arms. This is a gesture anathemic to modern sensibilities, thanks to its association with the minstrel 'blackface' phenomenon.) (The use of 'blackface'/'blacking up' is explored more thoroughly in our review of Speight's 1969 sitcom Curry and Chips, which has been released concurrently with this DVD issue of If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them.) 'Version One: 04/08/1968' (54:53) 'Version Two: 1974 version

Video

Both versions of the play are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. Break bumpers are present on both version. The 1968 version is in monochrome. Shot on videotape in a studio, it's in good condition. The 1974 version was also shot on videotape in a studio. It's well-preserved. Colours and contrast are good.

Audio

Both versions are presented with two channel mono soundtracks. These are efficient; there are no subtitles.

Extras

There is no contextual material.

Overall

Speight's comedy is essentially satirical and tends to focus on providing an ironic critique of the attitudes of the prejudiced characters (most famously, Alf Garnett) that populate Speight's work. However, Speight's satire did not always function in the way that its author planned: Tony McEnerny (2006) states that Speight intended Alf Garnett to be 'a distorting mirror in which we could watch our meanest attributes reflected large and ugly' (114). However, as Till Death Us Do Part progressed it became clear that there were elements within the sitcom's audience who identified with Garnett's worldview and laughed along with his rants rather than at them: Rhodes and Westwood (2008) note that Speight is 'a socialist satirist who intended that Garnett and his views look foolish, ignorant and outmoded – he was not, however, read that way by everyone’ (96). With the divided response to Till Death Us Do Part in mind, in relation to If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them John Twitchin (1988) claims that ‘The very title of Johnny Speight’s play revealed a fundamental dilemma which was also at the heart of its predecessor Till Death Us Do Part. In structuring the play around an overt bigot [the Blind Man], the play offered the viewer the choice – of dismissing the bigoted view as nonsense or of agreeing with them. The possibility that the good intentions might backfire was consistently underestimated’ within Speight's work (94). Whilst with this particular play, Speight could be said to have provided a pointed satire of prejudice and the anxieties that surround(ed) issues of ethnicity, the terms of racial abuse are, for modern audiences, challenging and as the play progresses they come fairly thick and fast. As Twitchin notes, there are points in If There Weren’t Any Blacks You’d Have to Invent Them were an audience might conceivably laugh along with the Blind Man's prejudiced worldview, rather than adopt Speight's intended reading of the play as a critique of the attitudes that are embodied in the Blind Man. With this in mind, the 1968 version is arguably slightly more effective and more 'grounded': aside from the more realistic setting, Leslie Sands' performance as the Blind Man invests the character with a venom and anger that is less present in the 1974 adaptation – in which Rossiter delivers the Blind Man's tirades with his characteristic sense of hysteria and panic. However, both versions of the play are interesting and make for fascinating companion pieces with one another. This DVD release of both versions of the play is very welcome, especially for fans of Speight's work; both versions of the play offer a satirical lens through which to view social ideas about ethnicity and class in the late 1960s/early 1970s. References: Andrews, Maggie, 1998: ‘Butterflies and Caustic Asides: Housewives, comedy and the feminist movement’. In: Wagg, Stephen (ed), 1998: Because I Tell a Joke Or Two: Comedy, Politics and Social Difference. London: Routledge: 50-64 Hooper, Mark, 2007: ‘Catch of the day? Is ironic racism still racism?’ The Guardian (20 November, 2007). [Online.] http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/tvandradioblog/2007/nov/20/catchofthedayisironicrac Hunt, Leon, 2010: ‘The League of Gentlemen’. In: Lavery, David (ed), 2010: The Essential Cult TV Reader. University Press of Kentucky: 134-41 Malik, Sarita, 2002: Representing Black Britain: A History of Black and Asian Images on British Television. London: SAGE McEnerny, Tony, 2006: Swearing in English: Bad Language, Purity and Power from 1586 to the Present. London: Routledge Oliver, John, 2003: ‘Johnny Speight’ (biography). ScreenOnline. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/465520/ Rhodes, Carl & Westwood, Robert Ian, 2008: Critical Representations of Work and Organization in Popular Culture. London: Routledge Shrapnel, Norman & Phillips, Mike, 2001: ‘Enoch Powell: An enigma of awkward passions’. The Guardian (7 February, 2001). [Online.] http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/0098/feb/09/obituaries.mikephillips Twitchin, John, 1988: The Black and White Media Book: Handbook for the Study of Racism and Television. Trentham Books Wagg, Stephen, 1998: ‘“At Ease, Corporal”: Social class and the situation comedy in British television, from the 1950s to the 1990s’. In: Wagg, Stephen (ed), 1998: Because I Tell a Joke Or Two: Comedy, Politics and Social Difference. London: Routledge: 1-31 Walker, Martin, 1977: The National Front. London: Fontana For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|