|

|

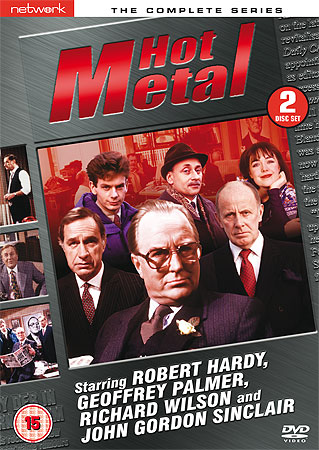

Hot Metal: The Complete Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th October 2010). |

|

The Show

Hot Metal: The Complete Series (LWT, 1986, 1988)

Taking its title from the familiar term denoting the traditional method for printing newspapers (in which the printing block was created by molten metal being poured into a mould), Hot Metal (LWT, 1986, 1988) was created and written by Andrew Marshall and David Renwick. Together, Marshall and Renwick had previously written the 1982 satirical sitcom Whoops Apocalypse for LWT. (Please see our review of Whoops Apocalypse) A dark and pointed satire of the years in which the Cold War was coming to a close, Whoops Apocalypse was produced at a time when alternative comedy was becoming popular on British television, and the series featured a mixture of the 'new' alternative comedians (such as Rik Mayall and Alexei Sayle) and recognisable faces from 1970s television sitcoms (John Barron and John Cleese). The series also featured a fresh, but arguably a little offputting conflation of the scattershot (and frequently crude) type of humour associated with the alternative comedy scene, and more traditional situation-based humour; furthermore, the quickfire structure (and disparate narrative events) of Whoops Apocalypse married the sitcom with elements of the television sketch show (the latter being the genre most commonly associated with the alternative comedians) – something which Renwick and Marshall had already attempted with their previous series, End of Part One (LWT, 1979-80). Hot Metal has a similar scattershot approach to Whoops Apocalypse However, Hot Metal's episodes are structured in a more conventional sitcom style. Like Whoops Apocalypse and End of Part One (which poked fun at the conventions of British television), Hot Metal is a satirical series in which Marshall and Renwick set their sights on the British tabloid press: Stephen Wagg (1998) has claimed that Hot Metal is an example of the postmodern situation comedies that appeared during the 1980s and which tended to examine 'life in some part of the communicatons industry' (23). More specifically, Wagg identifies Hot Metal as part of a group of sitcoms made between 1982 and 1994, also including Executive Stress (Thames, 1986-8) and Absolutely Fabulous (BBC, 1992-6), that feature journalists or publishers as their protagonists (ibid.). Wagg argues that these '[c]omedies which touch on the artifices of the media' are examples of 'postmodern culture' and are characterised by 'caricature, pastiche and postmodern irony, [with] characters based on cultural or media stereotypes, rather than on occupants of a purportedly real world' (ibid.: 23-4). For Wagg, these sitcoms are 'also, ultimately, an ingratiation with the audience—they say “We want you to know how all this stuff is put together, behind the scenes”' (ibid.: 24). For Wagg, the first of these postmodern, reflexive, media-conscious situation comedies was The Young Ones (BBC, 1982, 1984), which was populated by a rogues gallery of characters who parodied 'the stereotypes adults have created of young “folk devils” […]—the “hippie”, the “punk”—and they are placed in an often surreal setting (animals talk, characters eat bits of furniture […])' (ibid.). The Young Ones was shortly followed by a number of sitcoms that explicitly parodied recognisable genres: Brass (Granada, 1983-4; C4, 1990), 'a pastiche of the sagas of Yorkshire mill-owning families'; Allo Allo (BBC, 1984-92), 'a spoof on depictions of the French Resistance to the German Occupation in films about the Second World War' (ibid.); and Hot Metal, a satirical depiction of the British press which draws on elements of the Hollywood screwball comedies of the 1930s and 1940s.

Hot Metal revolves around the escapades of the employees of the Daily Crucible, a newspaper which (as one character notes in the first episode) has been labelled 'the product of a diseased mind'. Early in the first episode, we are shown a mock promotional video for the newspaper, in which the narrator intones that 'The Daily Crucible was set up eighteen months ago by a business consortium, with a mission to print the absolute truth, freee from bias' – and with that, we are ironically shown a headline declaring 'Dockers' Picket is “Calm and Peaceful”'. As the series opens, the editor of the newspaper, Harry Stringer (Geoffrey Palmer), is faced with rumours of his impending resignation. Stringer, described by the voiceover in the mock promotional video mentioned above as a man who was 'once named by a women's magazine as “the dullest man in Britain”', replaced the first editor of the newspaper, who (as depicted via a moment of physical comedy) threw himself from a window. Burdened with staff who are more interested in sleazy kiss-and-tell stories than the dry financial journalism that Stringer privileges, Stringer finds it impossible to improve the Crucible's finances. ('How can you write this salacious odium?' Stringer asks one of the paper's employees, the sleazy Greg Kettle – played by Robert Kane. 'Well, I suppose it's a gift', Spam replies.) The ailing Daily Crucible is eventually bought by Rathouse International, a company owned by Twiggy Rathbone (Robert Hardy). Stringer is given a new job role, executive managing editor – but nobody (including Stringer) knows what his new job title means. Meanwhile, the newspaper is given a new editor, Russell Spam (Robert Hardy). The new management push the Daily Crucible into a more salacious arena: in the third episode ('Beyond the Infinite'), a committee meeting is held to examine the specific motion of a woman's breasts that has 'proven maximum appeal', and the newspaper tries to improve its circulation by 'unveil[ing] its latest weapon in the circulation war', three-dimensional page three girls (using the technology of 'wobblevision'). Rathbone and Spam's tactics lead to Stringer lamenting, to a younger colleague (played by John Gordon Sinclair), 'It's criminal, Bill, what they're doing to the Crucible. Criminal'. However, as Bill notes, 'Circulation's shot up'. Stringer responds simply that 'Everything will shoot up, if you put naked women all over it [….] When I was a reporter of your age on the Macclesfield Echo, journalism was a fine, noble career – to serve society through the dispassionate execution of one's duty, free from corruption'.

Meanwhile, the paper uses increasingly underhand methods. Stringer claims that one of Spam's notes (outlining potential areas for investigation) reads 'Royal Baby?', and we cut to a shot of one of the reporters, Kettle, in a hotel room using a needle to pierce holes in condoms that Kettle has surreptitiously removed from a bedside cabinet. Caught by the presumed royal (clearly meant to look like Princess Diana) who's staying in the hotel room, Kettle is asked 'What gives you the right to break into hotel rooms and spy on girls in their underwear?' 'It's called the freedom of the press. It's what distinguishes our society from those in Eastern Europe', Kettle replies. The second series begins with Stringer's funeral; he is eventually replaced by Lipton (Richard Wilson, who would later take the lead role Renwick's long-running sitcom One Foot in the Grave; BBC, 1990-2000). Lipton is introduced as the television host of Lipton at Lunchtime. Describing the Daily Crucible as 'so dull, proof readers had been known to fall into a terminal coma while checking the terminal report', Lipton suggests to his viewers that Spam's 'racy storylines' led to success for the newspaper. Lipton interviews Rathbone, who, as Lipton puts it, aims to 'lose 60% of your workforce the British way, through a combination of natural wastage and industrial accidents'. After the interview, Rathbone recruits Lipton to be the Crucible's new managing editor, who in the words of Rathbone is to be 'an intellectual figurehead, a sham whose only purpose is to give the paper a spurious credibility in the eyes of the authorities'.

Hot Metal's jokes fly thick and fast, and the often quickfire dialogue suggests that Marshall and Renwick were drawing on the screwball newsroom-set comedies of the 1930s and early 1940s, including Howard Hawks' His Girl Friday (1940) – almost ten years before the Coen Brothers famously revisited the screwball genre with their 1994 film The Hudsucker Proxy. The jokes are a mixture of the topical and the slapstick; the topicality of some of the jokes may mean that new viewers need to refresh their understanding of the historical context in which the series was produced, or alternatively they may find themselves focusing on the crude 'alternative' jokes and moments of visual humour. (Some of the topical jokes could also be accused of tastelessness: in one scene, the characters are discussing the Arab-Israeli conflict, and the bullish Rathbone declares, 'If I want to see Jewish atrocities, I can go and see Sammy Davis Junior'; in the first episode of the second series, the Crucible tries to promote itself by publishing a list of all of the people in the UK who suffer from AIDS.) Disc One: Series One 1.'The Tell-Tale Heart' (24:07) 2.'The Modern Prometheus' (23:43) 3.'Beyond the Infinite' (24:20) 4.'Casting the Runes' (25:54) 5.'The Slaughter of the Innocent' (24:11) 6.'The Respectable Prostitute' (26:35) Disc Two: Series Two: 1.'Religion of the People' (25:14) 2.'The Joker to the Thief' (25:37) 3.'The Hydra's Head' (25:10) 4.'The Twilight Zone' (25:12) 5.'Crown of Thorns' (25:50) 6.'Unleash the Kraken' (25:51)

Video

Both series of Hot Metal are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 1.33:1. Presented in 1.33:1. Shot predominantly on video in a studio environment, the series has the crude, sometimes harsh aesthetic of much shot on video material of this vintage, with burnt-out highlights being quite common throughout the episodes. The episodes are well-presented here, and appear to suffer from no edits.

The original break bumpers are intact.

Audio

The episodes are presented with a two-channel stereo track. This is effective and clear; dialogue is audible throughout. There are no subtitles.

Extras

There is no contextual material.

Overall

Very funny at times and more disciplined than Whoops Apocalypse, Hot Metal highlights the ways in which modern journalism has turned increasingly towards cheap sensationalism – something arguably just as relevant to today's 'information age journalism' as it was to the 1980s. (See Network's recent release of Chris Atkins' 2009 documentary Star Suckers for a contemporary examination of this issue – reviewed here.) References: Wagg, Stephen, 1998: '“At Ease, Corporal”: Social class and the situation comedy in British television, from the 1950s to the 1980s'. In: Wagg, Stephen (ed), 1998: Because I Tell a Joke or Two: Comedy, Politics and Social Difference. London: Routledge: 1-31 For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|