|

|

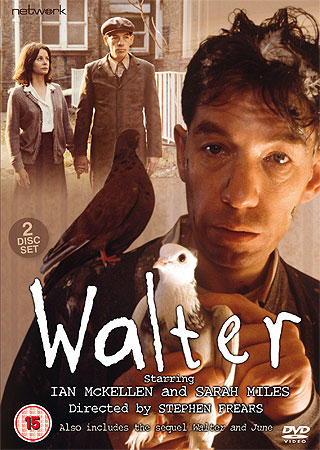

Walter (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (15th January 2011). |

|

The Show

‘Walter’ (C4, 1982) and ‘Walter and June’ (C4, 1983)

Made three years before Stephen Frears’ acclaimed ‘breakthrough’ film My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), ‘Walter’ (1982) was produced for Channel 4 and broadcast on the channel’s first night: it was the first entry into Channel 4’s long-running ‘Film on Four’ strand, for which Frears’ later films My Beautiful Laundrette and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987) were also produced. Many of Frears’ films of this period offered a critique of the treatment of disenfranchised groups in the era of the Thatcher government: in My Beautiful Laundrette, Frears examined attitudes towards race and homosexuality within an ‘ironic salutation to the entrepreneurial spirit in the 1980s that Margaret Thatcher championed’; in Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, in a ‘declaration of war on Thatcher’s England’ Frears turned his attention towards attitudes towards race and homelessness in South London (Barber, 2006: 209). With these films, Frears offered a challenge to the heritage tradition in British cinema, popularised in the 1980s by the period-set films produced by Merchant-Ivory; Frears criticised these historical dramas as ‘perpetrat[ing] myths about an England that no longer exists’ (Frears, quoted in ibid.: 211). Like My Beautiful Laundrette and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, ‘Walter’ offers a direct critique of 1980s Britain through an examination of attitudes towards a marginalised group, the handicapped, within a society whose treatment of the mentally handicapped is anitquated: an article on the BFI’s ScreenOnline website describes ‘Walter’ as ‘both a celebration of individual spirit and a critique of social responses to disability, as well as an expression of disillusionment with the Thatcher government's call for a return to Victorian values’ (Parker, 2003: np). During the 1970s, Frears had cut his professional teeth working on television plays for the BBC, and in one interview stated that his love of television derived from the medium’s ability to give ‘an accurate account of what it’s like to live in Britain – about men and women who go to work and lead rather desperate lives’ (Frears, quoted in Barber, op cit.: 211). These are the themes that drive the work Frears produced during the 1980s: this set of films show ‘a concern for the downtrodden and marginalised, and in his best work there is frequently an acerbic view of the condition of contemporary Britain’ (Shail, 2007: 71). The appearance of Channel 4 in 1982 – with its remit to address minority audiences – offered Frears, and many of his contemporaries, the ability to examine ‘under-represented’ issues and to ‘speak to the nation’; this has led to suggestions that ‘Channel 4’s films [of this era] can be regarded as a kind of public service cinema’ (Lay, 2002: 79). A Channel 4 commission allowed filmmakers like Frears to reach ‘a wider audience than the small independent cinemas and film festivals could manage’ (ibid.: 36). Adapted by David Cook from his novel, like many of Frears’ other films of this period (including My Beautiful Laundrette) ‘Walter’ offered a critique of the Thatcher-era’s treatment of disenfranchised groups. The play opens with a young Walter and his mother (Barbara Jefford) in the countryside; in longshot they are shown walking along a country lane. Walter’s mother lifts him onto the low wall of a footbridge over a train track, and they watch a train pass underneath. Walter’s mother chastises the boy, ‘I never had Jesus in me. You weren’t a child from him’.

From this opening sequence, Walter’s relationship with his mother is a core aspect of the narrative. Walter’s mother is his primary caregiver, but as we are introduced to Walter in later life (played by Ian McKellen) it is clear that his mother is conflicted about the responsibility of caring for her mentally handicapped son. ‘We don’t always do the things we like in this life, my lad’, she tells Walter whilst struggling to teach him to print his name: ‘You’ll find out soon enough when I’m dead and he’s [Walter’s father] too old and daft to take care of you’. Walter’s mother is also deeply religious, and relays her strong religious convictions to Walter; in a later scene, she pleads to God (‘Why did I give birth to one of your mistakes’) before telling Walter,’You must be the ugliest person in town, and you spent nine months inside me'. Meanwhile, Walter’s father (Arthur Whybrow) seems to have more patience with his son, teaching the boy how to care for his pigeons – creatures with which Walter seems to have a natural affinity. When Walter’s father dies, Walter’s mother tells the body, ‘I had to love you: I promised God I would’. Walter struggles to understand the passing of his father, which is his first encounter with death. The relationship between Walter and his mother becomes simultaneously more strained and more co-dependent. Through the lens of her religious belief, Walter’s mother tries to explain death to her son: 'Your dad's gone to sleep for a long time’, she tells Walter: ‘We won't see him again until we fall asleep forever. I know you miss him, but he's happy now: there are no problems where he is. We must be glad for him. We all fall asleep sometime. Jesus calls us, and we are glad to be called. It's beautiful then, the Day of Reckoning. We fall asleep, and Jesus decides if he wants you to live with him in Paradise. That's why it's important to be a good boy'. Walter works sweeping floors in a warehouse, where he is humiliated by the other staff, used as a figure of fun and referred to as ‘dribbler’, ‘spanner’ and ‘monkey’. The day after the death of his father, Walter is terrorized at work by some of the other workmen, who lock him in the warehouse overnight. 'Whose slimy, diseased prick did you dribble off the end of?', one of the men taunts Walter.

When Walter finds his mother dead in bed, he is unable to comprehend what has taken place; after his mother doesn’t wake, Walter brings his dead father’s pigeons into the house. Walter’s mother’s body is only discovered when a neighbour asks to see her and Walter tells the woman that his mother is ‘asleep’. The neighbour forces her way into the house and, finding the body, screams at Walter, ‘They’ll be coming for you. Don’t you worry. How can you let her go like that, covered in pigeon muck’. Now completely alone, Walter is taken to a hospital for the mentally handicapped. There, he is humiliated by being stripped naked and washed, and on his first night he is assaulted in his bed by one of the other patients. Walter’s experience of this fresh hell is relayed to the viewer, as Frears documentary-like camera depicts the inner workings of the hospital. Our empathy for Walter is matched only by the shame provoked by the unenlightened Victorian attitudes within the institution. (Frears may or may not have been influenced by the American filmmaker Frederick Wiseman’s controversial 1967 documentary about the Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane, The Titicut Follies.) The staff are occasionally cruel to the patients, who are treat more like inmates in a prison, but they can also be kind – and there is a subtle acknowledgement that they too are being stretched to breaking point. In one sequence, the patients are being shaved by one of the orderlies, and when one patient goes berserk and kills another patient, the frightened orderly turns a blind eye to the attack. The orderly asks Walter, the only cogent witness to the attack, to lie and cover up the negligence that led to the death: ‘There’ll be an enquiry and they’ll ask questions, Walter is told: ‘You’ll tell them that I did my best’.

However, Walter makes a friend in one of the orderlies (Jim Broadbent) who, recognising Walter’s abilities, enlists Walter to help clean up some of the other patients; however, the tasks include wiping the bottom of one of the paraplegic patients. Nevertheless, Walter opens up to his new friend, telling the orderly, ‘I want to make a baby’, and Walter’s relationship with the nameless orderly offers a brief glimmer of humanity in the film’s desolate landscape. As ‘Walter’ comes to an end and the patients celebrate Christmas with a show staged and viewed by the patients (much like the climactic patient-produced show that concludes Wiseman’s The Titicut Follies), Walter’s new friend confesses to Walter that, ‘By rights, you shouldn’t be here; and if your parents were still alive, no doubt you wouldn’t be’.

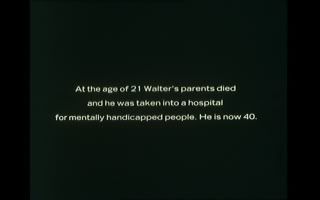

Produced a year later for the same Film on Four strand, ‘Walter and June’ (Stephen Frears, 1983) opens with a lengthy précis of ‘Walter’. Set nineteen years after ‘Walter’, with Walter now reaching the age of 40, ‘Walter and June’ was once again adapted by David Cook from his 1979 novel Winter Doves. Where ‘Walter’ had focused broadly on society’s treatment of the mentally-handicapped, ‘Walter and June’ examined the issue of the reproductive rights of that group.

One day, Walter sees June (Sarah Miles) and her baby son arriving at the hospital. The film shows us much documentary-like footage of the mothers who are patients in the hospital; conditions are poor, and some of the women are prone to bouts of rage. Walter, who is still helping the orderlies in the hospital, begins a friendship with June which develops into a tentative romance; June tells Walter about her infant son, declaring that, ‘They tell me that if I give him enough affection, and make him feel secure, he will grow up to be a normal, upright citizen [….] What they fail to tell me is, how do you give enough affection if you’re terrified’. Walter and June’s relationship develops, and when released from the hospital they move in together. However, Walter cannot understand June’s interest in him: ‘Why are you so nice to me?, he asks her. ‘Because I love you’, she tells him.

The couple struggle to reintegrate into society, with June showing Walter how to care for himself. However, one day June leaves Walter, and he is faced with trying to find a job. Distraught at June’s sudden and unexplained departure, Walter tries to track June down; his attempts to reunite with June lead to a compelling and tragic conclusion. Disc One: ‘Walter’ (70:23) ‘Walter and June’ (62:54) Disc Two: ‘Loving Walter’ (105:08)

Video

Shot on 16mm, both ‘Walter’ and ‘Walter and June’ have a stark, naturalistic documentary-like aesthetic, especially in the scenes set in the hospital. Both films have a bleached look and muted colour scheme; Walter’s early life (with his family and in his warehouse job) is presented in drab hues of green and brown, and the sequences set in the hospital are dominated by clinical whites, greys and blues. The drab and gritty look heightens the impact of the films and came to define much of Channel 4’s output during the 1980s, including Frears’ My Beautiful Laundrette.

Shot for television broadcast, both films (and Loving Walter, the feature-length edit included on disc two) are presented in their intended broadcast screen ration of 4:3. The original break bumpers are present on both ‘Walter’ and ‘Walter and June’.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track. This is clear throughout, proving adept at handling both quiet moments and the more cacophonous sound design of the hospital-set sequences. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

This two-disc DVD set also includes, on the second disc, Loving Walter (105:08), a feature film version made for release in America. Loving Walter edits together ‘Walter’ and ‘Walter and June’, losing some content but also gaining some newly-shot footage. It is an interesting, more easily digestible attempt to tell the story of Walter, but ‘Walter’ and ‘Walter and June’ are arguably more rewarding.

Overall

Although set somewhere in the 1950s, like many of Frears’ other films from the 1980s, ‘Walter’ and ‘Walter and June’ (set twenty years later) were clearly intended as critiques of the Thatcher era. They are difficult to watch and, at the time of their original broadcast, were highly controversial and helped to define the ‘gritty’ and socially-aware subject matter of the Channel 4 productions that would appear throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s. Both films are anchored by an exceptional performance from Ian McKellen, although it has to be said that Sarah Miles’ performance (as June) in ‘Walter and June’ is equally as good. Both films are harrowing to watch but ultimately rewarding; Frears shies away from sanitising the sufferings that are visited upon Walter. The documentary-like aesthetic is ugly and connotes ‘grit’. In all, both ‘Walter’ and ‘Walter and June’ are thoughtful, rewarding and exceptionally well-made dramas that are highly recommended. References: Barber, Susan Torrey (2006): ‘Insurmountable Difficulties and Moments of Ecstasy: Crossing Class, Ethnic and Sexual Barriers in the Films of Stephen Frears’. In Friedman, Lester D. (2006): Fires Were Started: British Cinema and Thatcherism. Wallflower Press: 209-222 Lay, Samantha, 2002: British Social Realism: From Documentary to Brit-Grit. Wallflower Press Parker, David, 2003: ‘Walter (1982)’. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/510827/ Shail, Robert, 2007: British Film Directors: A Critical Guide. Southern Illinois University Press For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|