|

|

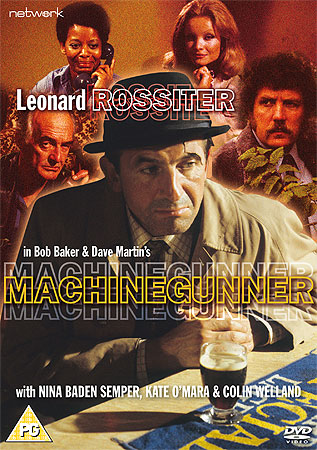

Machinegunner (The) (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (30th January 2011). |

|

The Show

The Machinegunner (Patrick Dromgoole, 1976), Network, 31 January 2011

Filmed on location in and around Bristol and written by the team of Bob Baker and Dave Martin, The Machinegunner (Patrick Dromgoole, 1976) offered Leonard Rossiter a (mostly) dramatic starring role a rarity in Rossiter's career after his success as Rigsby in Eric Chappell's Rising Damp (YTV, 1974-8). In The Machinegunner, produced for HTV, Rossiter plays Cyril Dugdale, a Bristolian 'machinegunner' (debt collector). Dugdale is introduced as he knocks on the door of a Sikh family; he has been charged with the task of evicting them, and there is more than a subtle suggestion that Dugdale enjoys his job. Shortly afterwards, Dugdale receives a telephone call; the female caller asks Dugdale if he 'does divorces'. Dugdale arranges to meet the woman, Felicity Ingram (Nina Baden-Semper), in a café; he is surprised to find that she is black. Ingram asks Dugdale to investigate 'a 50 year old businessman and his bit on the side'.

The target of Dugdale's investigation is 'property developer extraordinaire' John Sidney Arthur Bone (Colin Welland). Dugdale acquires photographic evidence of Bone's extramarital affair. However, Bone hires some thugs to obtain the negatives, forcing Dugdale to take shelter in Ingram's home. Dugdale gradually becomes aware that the job he has taken on is more than a simple investigation into an adulterous affair. After accidentally witnessing the murder of Bone whilst hiding from Bone's thugs, Dugdale confronts Ingram; she tells Dugdale that Bone is part of a property redevelopment scam. He buys areas that the council has marked for redevelopment, houses immigrants in them and drives the traditional tenants out, decreasing the value of the houses in these areas. Bone is then given permission to redevelop the area, getting 'massive compensation, plus the price of the land'. The scenario benefits both Bone and the city council. Ingram is working on the production of a television documentary about corruption. However, Dugdale is aware that what Bone has been doing is not criminal: 'It's not crime, see', he tells Ingram; 'it's business, you see, the way it's done you know, a few backhanders'. Ingram is happy to see the back of Bone, 'a pig', but she is fully aware that behind him 'is some other white bastard': a local councillor, Geoff Livingston (Ewen Solon). However, with the death of Bone, Ingram also seems to become a target: she is attacked and her home is turned over by a group of hired thugs. When Bone's body turns up at the home of his lover Pat Livingston (Kate O'Mara) the wife of Geoff Livingston, who it turns out is the man who had Bone killed Dugden and Ingram find an unlikely ally.

Within the opening scenes depicting Dugdale's eviction of the Sikh family and his first meeting with Ingram, some of the core thematic territory of The Machinegunner is sketched: race relations in multi-cultural British cities. Dugdale's racial prejudice (which surfaces most directly when, later, he challenges Ingram, declaring 'You? What are you? Just a bloody jumped-up, la-de-da, black enamel jungle bunny, that's what you are') and his 'culture clash' relationship with his British Afro-Caribbean client are presented as subtly metonymic of wider attitudes towards race in 1970s Britain: Bone's plan involves tapping into the prejudices of white society, renting houses to immigrants (presumably ethnic minorities) as a way of encouraging the existing white tenants to vacate their homes. The divisions between different ethnic groups are foregrounded in two scenes: in one of these scenes, Dugdale enters an all-white pub; in another scene, Dugdale finds himself in an all-black nightclub. The Machinegunner subtly deals with issues of race and prejudice in 1970s multicultural Britain, but only subtly; the drama has none of the courage of the BBC's Gangsters (1976-8), which began in the same year and, within the framework of a crime drama, confronted race relations within Birmingham. At the core of Bone's scheme is the relationship between Bone and the corrupt Geoff Livingston. The relationship between 'property developer extraordinaire' Bone and corrupt councillor Livingston seems like a thinly-veiled fictionalisation of the John Poulson-T. Dan Smith scandal. In 1974, Smith (the leader of Newcastle City Council from 1960 to 1965, dubbed 'Mr Newcastle' by some parts of the media and 'The Mouth of the Tyne' by others) pleaded guilty to corruption and was sentenced to six years in prison. By 1976, architect Poulson's corrupt relationship with Smith, driven by both men's desire to redevelop large parts of Newcastle, had proven to be fertile ground for other crime dramas: it had already formed a core part of Mike Hodges' Get Carter (1971), via the character of corrupt businessman Cliff Brumby (Brian Mosley), and would later be dramatised in Peter Flannery's 1982 play Our Friends in the North (adapted by the BBC in 1996). One sequence, in which we are shown Bone on the site of a large modern building that is in the process of being erected, is reminiscent of the scene in Get Carter in which Brumby consults his architect atop the car park being built by Brumby's firm (in reality, the Trinity Centre in Gateshead), which Hodges described in 2010 as 'a monumental example of Sixties British brutalist architecture' (Hodges, 2010: np). In One Night Stands: A Critic's View of Modern British Theatre (2002), Michael Billington describes Rossiter's great talent as lying in 'his great comic capacity for playing men who were prey to some ungovernable obsession [ .] Great comic acting is often about single-mindedness; and Leonard Rossiter conveyed better than anyone [...] the tunnel-vision of the truly possessed' (226). Frank Marcus once stated something similar, declaring that in his performances, Rossiter invariably had 'something obsessive in his eyes; he was forever walking tightropes. He moved as if he were expecting to be hit over the head from an unexpected quarter. His sharp yet resonant voice was apt to change gear suddenly into hysterical falsetto. The world was a dangerous place' (Marcus, quoted in Slide, 1996: 214).

Here, as Dugdale, Rossiter is given a mostly straight dramatic role with an undercurrent of comedy arising from the character's increasing paranoia; Dugdale is initially used as a pawn, and Rossiter manages to make Dugdale's gradual realisation that he is being used as a middleman by more dangerous game both frightening and funny. Here, Rossiter inhabits Dugdale and makes strong use of what Berkoff described as Rossiter's 'strong Midlands twang [which] coloured his voice [and] gave such vinegar to his performances' (Berkoff, 2003: 17). In The Machinegunner, Rossiter is convincing as Dugdale, the type of character that Rossiter excelled at playing: a man who, despite his prejudices, is sympathetic because of his powerlessness, prone to bouts of hysteria and manipulated by forces outside his control. However, the real gem here is Nina Baden-Semper, known by most people for her performance as Barbie Reynolds in Love Thy Neighbour (Thames, 1972-6); as Felicity, Baden-Semper spars perfectly with Rossiter's Dugdale, acting as a femme fatale of sorts, drawing an unwitting Dugdale into her scheme to expose the corrupt relationship between Bone and Livingston. Running time: 78:50 mins (PAL).

Video

The Machinegunner is presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. Shot on location and entirely on film, The Machinegunner looks very good on this DVD release; the film has a strong sense of time and place, and the DVD presentation is solid and film-like. The original break bumpers are present.

Audio

Audio is presented via functional, clear two-channel track. There are no subtitles.

Extras

None.

Overall

A solid drama, The Machinegunner benefits largely from the interplay between Rossiter and Baden-Semper's characters. It is a film very much of its time, dealing with issues at the foreground of British culture during the 1970s, including multiculturalism and race relations, and corruption in local government. There are some great little touches: the opening titles play out over posterised images of the demolition of old houses (prescient of the issues dealt with later in the drama) and the sound of a jackhammer which acts as an aural metaphor for the machine gun alluded to in the drama's title. (The association of people and buildings is consolidated later in the drama, when Bone asserts via the telephone that Dugdale is 'crumbling very nicely' much like the buildings that are being demolished during the opening titles sequence.) Another similar moment occurs later, when whilst using a public telephone Felicity refers to Dugdale's trade as a 'machinegunner'; a pronounced rat-a-tat-tat is heard, again acting as an aural metaphor for a machine gun. However, the sound is revealed to be nothing more than Dugdale tapping on the glass of the telephone box. The Machinegunner is an interesting and engaging way to spend 80 minutes, but in its coverage of issues of race and corruption it is arguably less rewarding (or brave) than a contemporaneous series such as David Rose's Gangsters. Nevertheless, fans of Rossiter will find much to enjoy here. References: Berkoff, Steven, 2003: Tough Acts. London: Robson Billington, Michael, 2002: One Night Stands: A Critic's View of Modern British Theatre. London: Nick Hern Books Hodges, Mike, 2010: 'A concrete monstrosity, but it was perfect for my film'. The Independent (26 July, 2010). [Online.] http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/mike-hodges-a-concrete-monstrosity-but-it-was-perfect-for-my-film-2035420.html O'Mara, Kate, 2004: Vamp Until Ready. London: Robson Slide, Anthony, 1996: Some Joe You Don't Know: An American Biographical Guide to 100 British Television Personalities. London: Greenwood Publishing Group For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|