|

|

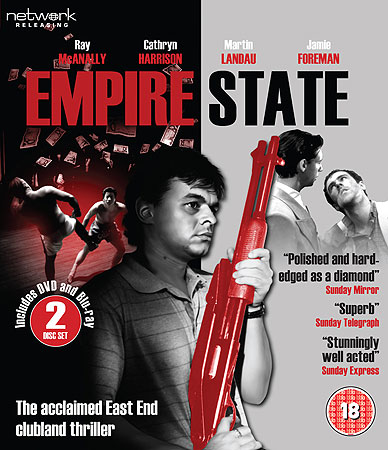

Empire State (Blu-ray)

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th March 2011). |

|

The Film

Empire State (Ron Peck, 1987) British director Ron Peck is probably still most well-known for his acclaimed 1978 drama Nighthawks, which revolves around the ‘coming out’ of a gay secondary school teacher; Nighthawks was notable because, in the words of Helen de Witt (for the BFI’s ScreenOnline resource), ‘[i]t was Britain’s first explicitly gay film set in the gay community’ (2003: np). Since Nighthawks, Peck has dabbled in a variety of genres, making documentaries and narrative features. As de Witt notes, Peck’s work displays a truly maverick sensibility in his decision to refuse ‘work within the traditional film industry, which may have meant compromising his vision and his principles’ (de Witt, 2003a: np). Partly produced by FilmFour, Peck’s 1987 feature Empire State is broadly comparable to a number of other British crime films of the 1980s, including The Long Good Friday (John Mackenzie, 1980), Neil Jordan’s Mona Lisa (1986) and Mike Figgis’ Stormy Monday (1988). This group of films showed a film noir-like fascination with corruption and explosions of sudden violence in urban settings. Some critics have commented that British crime films of the 1980s, such as those mentioned above and others including Stephen Frears’ The Hit (1984) and Mike Newell’s Dance with a Stranger (1985), are comparable to the films that made up the ‘neo noir’ (or ‘noir lite’) movement in American cinema at the same time: films such as James Foley’s After Dark, My Sweet (1990), the Eighties remakes of D.O.A. (Annabel Jankel & Rocky Morton, 1988) and The Postman Always Rings Twice (Bob Rafelson, 1981), and Michael Mann’s films Thief (1981) and Manhunter (1986). Citing John Hill, Andrew Spicer has claimed that through these British films’ focus on the figure of the gangster, the pictures ‘mounted a critique of Thatcherism’ (2002: 196).

Foregrounding its setting in Thatcher’s Britain, Empire State’s narrative deals obliquely with the redevelopment of the London Docklands and, more broadly, the ways in which the fabric of British society was changing during the era. The film opens with an effective and elliptical sequence: disembodied screams and snatched images are interspersed with moments of blackness. ‘What about her?’, a male voice asks. Another man’s voice responds, ‘She don’t know nothing. Just some old scrubber he picked up’. After this, the film proper begins when we are presented with a close-up of a young woman, Marion (Cathryn Harrison), who climbs out of a crashed car and finds herself on a deserted London street. The eerie emptiness of the urban setting brings to mind the opening sequence of The Omega Man (Boris Sagal, 1971), in which Charlton Heston, the apparently sole survivor of a mysterious virus, explores a deserted Los Angeles – or, more closer to home, the early sequences of Danny Boyle’s 2002 horror film 28 Days Later, in which Cillian Murphy picks his way through an abandoned London. Soon, Marion finds herself in the reception area of offices belonging to a newspaper; the lack of human presence is reinforced when a disembodied electronic voice promises that ‘Someone will be with you shortly’. Marion creeps hesitantly through the building until she reaches an office; on top of a desk sits an electronic typewriter, its keys spattered with blood, and a postcard showing the neon-drenched entrance to a nightclub, the neon-lit words ‘Empire State’ emblazoned above the door of the building depicted in the photograph. The postcard seems to inspire a moment of aural analepsis, the disembodied screams and sounds of panic momentarily returning to the soundtrack before abruptly ending as the film cuts to a train station where a young blonde man, Pete (Jason Hoganson), holds the same postcard and makes a telephone call. The recipient of Pete’s telephone call is Cheryl (Elizabeth Hickling), an attractive brunette who is visibly disturbed by Pete’s call. She puts the receiver down mid-conversation, and when her boyfriend Danny (Jamie Foreman) enters the room, she tells him that the caller was ‘asking about Mick’ before complaining that she is unhappy with the flat in which she and Danny live. ‘It takes money; it takes time’, he tells her, promising he’ll ‘do the place up for you’. ‘Time’s running out’, she complains. The couple are in debt, and Cheryl goads Danny to ‘do it’ – the ‘it’ presumably being a robbery. Later, Danny tells Cheryl that he won’t commit the crime. ‘You can be such a fucking wimp’, she responds bitterly, her chiding and emasculating manner foregrounding her status as the film’s femme fatale. Elsewhere, Johnny (Lee Drysdale), a cocky male prostitute, is being driven through London in a flashy open-top car; the two other occupants of the car, a man and a woman, tell Johnny to earn them so money. Meanwhile, we are reintroduced to Marion, who whilst at work telephones the number attached to a personal ad in the newspaper. The number promises ‘Handsome leading light of stage and screen seeks intelligent, sensuous woman to share exciting lifestyle’. Meanwhile, a visiting American investor, Chuck (Martin Landau), is shown plans to regenerate and rebrand London’s Docklands, a controversial project that will further underscore the differences between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’. Later, in his hotel room, Chuck enlists the services of Johnny, who has also been seen initiating Pete into the life of a male prostitute.

The lives of this disparate group of characters intersect during a busy night in the Empire State nightclub, where a conflict brews between old-school East London villain Frank (Ray McAnally) and the younger Paul (Ian Sears); Paul is a new breed of gangster who has courted the wealth of West London and, much to the chagrin of Frank, has become involved in selling ‘designer’ drugs. When Frank refers to Paul’s ‘poncey friends’, Paul tells him, ‘You don’t even know who those people are: they own this place. You see, Frank, this part of London’s changing. It’s coming back to life. There’s a new class of money coming in. This place will be pulled apart brick by brick, and put back together with a bit of taste, a bit of style. Thought I’d have you stuffed and put in a glass case as a reminder of the past’. Paul dismissively describes Frank’s style as the ‘old East End chat, the filthy language and the threats of violence’, and Frank challenges Paul to gamble on an underground boxing match held within the Empire State itself; the match becomes the site of symbolic struggle between the old and the new. The stage is set for an explosion of violence both in and outside the nightclub, as Cheryl – who works in the club – humiliates and abandons Danny for another man, Vince (Glen Murphy), and a heavily-armed Danny advances towards the Empire State. All of the characters in the film are willing to get ahead in whatever way they can. Those at the bottom of the heap are literally, or metaphorically, selling themselves, and the film depicts Eighties Britain as a place characterised by the commodification of the self – a world in which people are little more than consumer objects, things to be bought and sold, used and discarded. Desire is an accepted – and unquestioned – currency for the young people in the London depicted in the film.

The film is highly critical of the Thatcher era, and in an interview circulated by Network to promote this DVD release Ron Peck reflected that ‘It was all about money. It was also a time when co-writer and executive producer Mark Ayres and I felt there was a fierce new individualism coming to the fore in Britain. Under Margaret Thatcher people were cut loose and a lot of the safety nets were removed. The country was volatile and moving to extremes [….] There was immense frustration and anger at the changes taking place. The yuppie became a particular hate figure. Warehouses were mysteriously burning down in just those areas developers had their sights on. The new possibilities for making money, the sheer greed, made for a new ruthlessness and violence, including violence of language. It felt very much like an “every man for himself” world. The old East End had to either hold out or join in’. As in the satirical depiction of the greed of Reagan’s America in Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987) – in which the all-powerful Omni-Consumer Products bankrolls criminal activity as a means of legitimising their plan to clear Old Detroit to make way for their new corporate utopia, Delta City – Empire State casts its critical eye over the concept of urban renewal and, specifically, the regeneration of the London Docklands. Chuck is introduced in a sequence which begins with a series of helicopter shots of the area. A disembodied voice, later revealed to belong to Mr Cavendish (David Lyon), declares that, ‘You must forget about what it used to be like here: there’s a new Britain emerging. Fitter, leaner, hungry to compete, ready to assert itself in the world’s financial arenas. A new nation needs a new kind of city, so we’re building it. The whole of the East End is being cleared out and cleaned up… streamlined’. ‘What about the unions?’, Chuck – offscreen – asks. ‘They’ve been given a sound thrashing, and now they’ve seen sense. What we’re attracting here is a new breed altogether: tough, motivated, ambitious. Anyone who wants to stay in the race for the Twenty-First Century is moving in now’. After the helicopter lands, Chuck is ushered into a corporate building and shown an architectural model of the development. One of the executives in charge of the development, Wellington Horne-Ryder (Tim Brierley), bluntly asserts that he’d like to ‘blow up’ the council houses near the development but has managed to ‘screen them from view’. Later, when Johnny arrives at Chuck’s hotel suite and sees Chuck looking out of the window at the city streets, Johnny asserts, ‘What can you learn from looking out there? Fucking desperation’. The dreary desperation of Cheryl and Danny, Marion, Pete and Johnny is given a counterpoint in the high glamour of the Empire State nightclub, whose entrance is drenched in neon and whose interior is decked out with large murals depicting images from Hollywood’s Golden Age. Aside from the patrons, the club is populated by both criminals and yuppies; it quickly becomes apparent that these two groups aren’t mutually exclusive. ‘I bought a studio just down the world a year ago; it’s almost doubled its value’, one well-heeled drug peddler tells a woman in the club.

Male and female bodies alike are fetishised in an extended montage depicting the young people preparing for a night out at the Empire State club. However, despite its glamour the Empire State is a place in which dreams are broken: Marion meets her ‘Handsome leading light of stage and screen’ and finds him to be a huge disappointment. ‘God, he’s awful’, she tells the friend who has accompanied her to the club. When Danny arrives and is served by Cheryl, he is piqued by her dismissive attitude and her association with Vince; desperately, he tells Cheryl that ‘Everything’s gonna be alright. You’re gonna be fucking proud of me’. The only relationship that ends on a positive note is that between Johnny and visiting American Chuck. After their encounter in his hotel suite, Chuck buys Johnny an expensive dinner and asserts, ‘It’s been a pleasure doing business with you’ (as with other relationships in the film, Johnny’s encounter with Chuck is reduced to an economic exchange). Enchanted by the promise offered by America and disillusioned with his life in Britain, Johnny leaves London, following Chuck to New York. For its depiction of the conflict between the values represented by Frank and Paul, Empire State has been grouped together with films such as Neil Jordan’s Mona Lisa and The Young Americans (Danny Cannon, 1993); according to Steve Chibnall and Robert Murphy (1999), these three films ‘contrast old-style Cockney villains with newer, more ruthless elements […] a different sort of gangster who has thrown aside the old criminal code and moved into the despised but increasingly lucrative areas of drugs and prostitution’ (13). Like Mona Lisa – in which George (Bob Hoskins), an old-school criminal who has recently been released from prison, is sent on ‘a nightmare journey through a new, exploitative underworld of crime characterised by sex clubs, pornography, drug-dealing and prostitution’ – Empire State depicts ‘the clash between old and new London’ (Hill, 1999: 168, 170). Like many classic films noirs – such as The Killers (Robert Siodmak, 1946), Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950), The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946) and Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) – the bulk of Empire State is told in fatalistic flashback, with the opening sequence depicting Marion’s return to consciousness in an eerie, deserted London functioning as a framing device. (Citing J P Telotte, Mark Bould claims that after Double Indemnity, ‘over forty film noirs […] utilise[d] flashback narrative’; 2005: 22.) The film has no single protagonist and interweaves a number of narrative strands that all come together in the Empire State nightclub.

On the commentary track that is included on this release of Empire State, Ron Peck and Mark Ayres state that the film was influenced by classic films noirs ‘and a bit of Douglas Sirk’. Reflecting on Empire State’s relationship with film noir, John Hill has described the picture as ‘a curious hybrid of film noir, melodrama and social comment’ (op cit.: 173). Hill argues that like The Long Good Friday and a number of other British crime films of the 1980s (for example, Stormy Monday), Empire State allegorises ‘the rise of Thatcherism’ and ‘the emergent enterprise culture of the 1980s’, which was dominated by ‘the economic themes of self-interest, competition and “freedom”’ (ibid.: 172). In the film, this is represented through the conflict between the ‘distinct types of gangsters, symbolic of the social and economic changes around them’ (ibid.: 173). Frank, like Shand (Bob Hoskins) in The Long Good Friday, is ‘represent[ative of] the old East End’ and ‘maintains certain “standards” and refuses to deal in drugs’ (ibid.). Frank’s patriarchal role is ‘challenged […] by his protégé, Paul (Ian Sears), who has “crossed over” into pimping and drug-dealing’ (ibid.). The conflict between Frank and Paul comes to a head when Frank challenges Paul to gamble on an illegal fight, ‘which clearly symbolises the battle between the two East Ends’ (ibid.). Frank wins, and as Hill notes, ‘the film ends up (for all its savagery) reworking a theme that is typical of much British cinema—the triumph of the small man, or small businessman, over impersonal economic forces’ (ibid.: 173-4). The film is uncut and runs for 102:40 mins.

Video

Empire State is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1, which should approximate the aspect ratio of its original cinema release. The transfer is handsome and film-like, with good contrast levels, a solid (and deep) image and a natural layer of film grain. This is a very pleasing presentation of a movie that has been fairly hard to see since its initial release.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo Linear PCM track. This track offers a good, solid soundscape for the film; dialogue is clear throughout, and the music bursts through the speakers at a high level.

Extras

The disc offers the following contextual material: A commentary track with Ron Peck and Mark Ayres. This offers quite a lot of descriptive discussion of what takes place on screen, but Peck and Ayres offer some strong insights into the film and the context in which it was made. The film’s trailer (2:31). This is an exciting trailer that offers an almost Situationist-like use of sloganeering in its voice-over narration: ‘It’s the heat of the city, it’s the smell of money, it’s the taste of power, it’s a city that’s changing and if you know what you want, it’s there for the taking, it’s the taste of fear, it’s the trouble that won’t go away, it’s the heat of the night, it’s the taste of pleasure, it’s a one-way ticket to a land of dreams. Empire State. This is London like you’ve never seen before, and tonight’s a night you’ll never forget. Empire State, a night on the edge’. Image Gallery (2:33): a collection of promotional images and character shots. Costume Research Gallery (0:45): images of some of the costumes used in the nightclub sequence. Design Gallery (2:18): storyboards and images of the design of the exterior of the Empire State club, its logo, a floorplan of the club.

Overall

Sadly largely forgotten, despite being quite controversial on its original release, Empire State has a similarly sleazy atmosphere (and a strikingly similarly-sounding soundtrack) to American thrillers such as Abel Ferrara’s Fear City (1984); in its representation of the London underworld, the film also bears comparison with Pete Walker’s Moon/Man of Violence (1969), recently released on DVD and Blu-Ray by the BFI (as part of their ‘Flipside’ series). The film offers a strong critique of the Thatcher era, comparable to American films such as Verhoeven’s RoboCop, and also represents one of a group of British films that been grouped with the ‘neo-noir’ movement. Empire State is a thoughtful, affective and enjoyable film that deserves to be seen by a wider audience. Hopefully, this new release by Network will enable that to happen. References: Bould, Mark, 2005: Film Noir: From Berlin to Sin City. London: Wallflower Press Chibnall, Steve & Murphy, Robert, 1999: ‘Parole overdue: Releasing the British crime film into the critical community’. Chibnall, Steve & Murphy, Robert (eds), 1999: British Crime Cinema. London: Routledge: 1-16 De Witt, Helen, 2003: ‘Nighthawks’. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/548405/ De Witt, Helen, 2003a: ‘Peck, Ron (1948- )’. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/548369/ Hill, John, 1999: ‘Allegorising the nation: British gangster films of the 1980s’. Chibnall, Steve & Murphy, Robert (eds), 1999: British Crime Cinema. London: Routledge: 165-76 Spicer, Andrew, 2002: Film Noir. London: Pearson Education Please note that the images used in this review are for illustration purposes only and are not intended to reflect the quality of this specific release. For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|