|

|

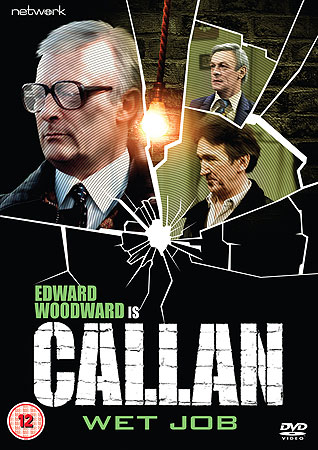

Callan: Wet Job (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th March 2011). |

|

The Film

Callan: Wet Job (Shaun O’Riordan, 1981)

A landmark series, Callan (ABC/Thames, 1967-72) is one of the crowning gems of British television drama; like Sidney Furie’s 1965 adaptation of Len Deighton’s The IPCRESS File, Callan offered a downbeat antidote to the increasingly fantasy-based landscape of the James Bond films. The series was created by James Mitchell and grew out of ‘A Magnum for Schneider’ (1967), an episode of ITV’s single play strand Armchair Theatre (ABC/Thames, 1956-74). Callan survived for four series, the last two of which were produced in colour by Thames Television. The series’ creator, James Mitchell, delivered five novels based around the character of David Callan (played to perfection in a career-defining performance by Edward Woodward), beginning with Red File for Callan in 1969; and in 1974, ‘A Magnum for Schneider’ was reworked as a theatrical feature, Callan (directed by Don Sharp).

In the character of David Callan, the series featured an ‘everyman’ working-class protagonist (in the vein of The IPCRESS File’sHarry Palmer), with whom the majority of television viewers could sympathise. A specialist in assassinations, Callan works for ‘the section’, a counter-espionage unit. Throughout the series, he operates under a number of senior officers, who all share the codename ‘Hunter’. The various Hunters are interchangeable agents of bureaucracy, and this aspect of the series has led some commentators to draw comparisons between the role of Callan's numerous Hunters and the succession of Number 2s in The Prisoner (ITC, 1967-8) (see Clark, 2003: np). Callan is frequently railroaded by ‘the section’, which at times seems to function as a Kafkaesque bureaucracy; Callan thus often finds himself placed in a ‘trick bag’, either framed by the section or abandoned to the enemy. He is frequently a helpless witness to the execution of innocents, and his conscience often leads him to question the actions that he is forced to carry out. His informant and accomplice, the pitiful Lonely (Russell Hunter), is frequently left ‘high and dry’ by the section, despite Callan’s attempts to protect him. This 1981 television film, Wet Job, represents the last outing for David Callan and was written by James Mitchell. The film opens with Callan at home, with his landlady and sometime lover Margaret Channing (Angela Browne). Callan is living under the assumed name of David Tucker; he has retired from the section and runs a shop selling military memorabilia. Returning to Margaret’s home, he carries with him a reproduction of Goya’s ‘The Shootings of May Third’, which Margaret finds grotesque.

Margaret holds a party at which Callan meets Lucy Robertson Smith (Helen Bourne), Margaret’s niece and a lecturer in philosophy at Oxford. When Lucy asks Callan if he lives in Margaret’s house, he tells her that he is Margaret’s lodger. Overhearing the conversation between Lucy and Callan, another couple make a joke about Hitchcock’s 1927 To this, Callan dryly responds, ‘No, I haven’t murdered anyone for years’. Callan is called in to the section by the new Hunter, who has been in Washington for most of his career. Callan asks after his old colleague Meres, who moved to America to work for the section. Hunter tells Callan that Meres is dead, having been killed by a jealous husband rather than by a member of ‘the opposition’. Referring to Callan as ‘frightfully good, you know: the most efficient killer we ever had’, Hunter asks Callan to reflect on a man named Daniel James Haggerty (George Sewell), a ‘great champion of the poor and downtrodden’. Haggerty was apparently friendly with another man named Millington: ‘Awful fellow, wasn’t he [….] Betrayed everybody’, Hunter observes. Callan killed the double-dealing Millington, who was involved in a romantic relationship with Haggerty’s daughter Jenny; Millington’s death caused Jenny to develop a strong reliance on cigarettes, leading to her death from lung cancer: ‘one of life’s little ironies, no more’, Hunter notes. Hunter states that Haggerty, who blames Callan for his daughter’s death, is writing his memoirs and plans to name and expose Callan, and as Hunter dryly notes, if Callan’s identity is revealed, ‘a lot of old friends might want to pay their respects’. ‘How can he name me? Because I don’t exist, do I?’, Callan states.

Hunter reveals that Haggerty has a ghostwriter for his memoirs, Lucy Robertson Smith, Margaret’s niece. Callan begins to suspect that Margaret may have been watching him for the section, but Hunter tells him that this isn’t the case. ‘I’m merely pointing out to you that you have a choice, between going to prison for a long time and taking certain steps’, Hunter tells Callan, suggesting that Callan kill Haggerty. ‘All those years ago: “It’s over”, they said. “Why don’t you just go back home and take your pension and start your little business? Because it’s all over”, they said’, Callan reflects sadly. ‘Well, you know they lied’, Hunter reminds him: ‘it’s never over’. ‘Sod you all… all of you’, Callan declares softly. Reluctantly, Callan accepts the job of executing Haggerty. Meanwhile, Lucy is involved with a philosophy lecturer, Dobrovsky (Milos Kirek), who is associated with Haggerty. A radicaliser of students, Dobrobsky has disappeared; he is being held captive by the French, who threaten to sell him as a traitor to the KGB. Lucy approaches Haggerty, asking him to provide the cash with which to pay the ransom for Dobrovsky, but unbeknownst to her Haggerty has already been set the task of executing Dobrovsky for his betrayal of the KGB. It has to be said that Wet Job is a disappointing final bow for David Callan. Despite strong performances all-round, especially from Woodward and Hunter, who wear their respective characters like a second skin, Wet Job has a cheap and rushed feel. The film is clearly studio-bound, shot entirely on video, and suffers from a distractingly insistent synth score.

What is interesting about Wet Job is the chance it offers for viewers to ‘catch up’ with Callan and his accomplice Lonely. As Wet Job opens, we find that Callan has become involved in an odd relationship with his landlady, Margaret. Callan is Margaret’s sometime lover, and Callan seems to be in a subservient role to Margaret. At the party, he is ridiculed by Margaret’s son, Robin, and we are presented with a series of shots from Callan’s point-of-view: canted angles are used to show his disorientation and disengagement from the party, especially after experiencing abuse from Robin. The use of the camera in this sequence is reminiscent of the disorienting point-of-view shots in the pivotal party sequence in John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1968). In Seconds, Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph) is – through surgery – ‘reborn’ as Tony Wilson (Rock Hudson); Wilson hosts a cocktail party and struggles to fit in, his dislocation with his surroundings communicated through expressionistic point-of-view shots. A deadly shot with a pistol, Callan’s increasing age is also alluded to later, when during the climax he has to adjust and clean his spectacles before taking aim.

Meanwhile, Callan encounters Lonely. In the series, Lonely is a pitiful man who emits a foul scent when frightened. Here, Callan is surprised to find that Lonely has found it easier to conform than Callan himself: Lonely has found work as a plumber, after learning the trade ‘in the nick’, and is engaged to a younger woman named Mariella. As in many episodes of the original series, Callan has to persuade a reluctant Lonely to do some work in him: when first approached by Callan, Lonely turns down Callan’s offer of work because he doesn’t want ‘no more holes in me’. Needless to say, as with many episodes of the original series, at the end of Wet Job Callan discovers that he has once again been betrayed, and has been used as little more than a pawn in a much bigger game.

Wet Job runs for 81:20 mins (PAL) and is uncut.

Video

This television film is presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. The break bumpers are intact.

Shot on video and studiobound, Wet Job looks surprisingly good here, with little wear and tear present throughout the film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track. There are no subtitles, but dialogue is clear and problem-free. However, Wet Job is saddled with a score that is at times wildly distracting.

Extras

Image Gallery (51s).

Overall

Woodward, as always, is excellent in the role of Callan, and Wet Job has a very strong supporting cast, including Russell Hunter and George Sewell. The film is interesting in its depiction of Callan’s inability to conform to conventional society, and its juxtaposition of these scenes with Lonely’s apparent success at ‘fitting in’. James Mitchell’s script also comfortably recycles the structure of many of the original episodes (Callan is reluctantly hired by ‘the section’ to do a job, sub-contracts an equally reluctant Lonely to help him and discovers after the resolution that he has been used as a pawn), showing a confident grasp of the thematic territory of the series. However, Wet Job has a cheap, studiobound appearance and a truly distracting synthesised score. Fans of the superb original series will find Wet Job somewhat rewarding, but in all this film’s reputation as a disappointing final bow for the character of David Callan is deserved. Viewers new to Callan would be advised to start with either the series itself (also available from Network) or the 1974 feature film. For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|