|

|

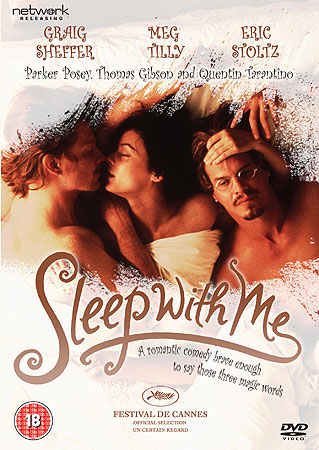

Sleep With Me

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th June 2011). |

|

The Film

Sleep With Me (Rory Kelly, 1994)

Promoted (and remembered) as the film which features a show-stopping cameo by then-young turk Quentin Tarantino, Sleep With Me (Rory Kelly, 1994) was part of a wave of Gen X romantic comedies that appeared during the early 1990s, including Reality Bites (Ben Stiller, 1994), Singles (Cameron Crowe, 1992) and Party Girl (Daisy von Scherler Mayer, 1995). In Tarantino’s brief cameo - which in the promotion and, arguably, reception of the film overshadowed the content of the narrative – he appears at a party and delivers a typically allusive speech in which he ‘queers the straight text’, identifying the supposed homoerotic subtext in Tony Scott’s Top Gun (1986), the defining blockbuster of the New Hollywood era: a mode of filmmaking against which the independent filmmakers associated with the ‘Generation X’ phenomenon rebelled. ‘What is really being said?’, Tarantino’s character, Sid, asks one of the other partygoers. ‘You want subversion on a massive level?’, he queries before asserting that Top Gun is one of the greatest scripts in the history of cinema because ‘it is a story about a man struggling with his own sexuality’.

Tarantino’s cameo interrupts the narrative, which is a familiar tale of unrequited love and secret passions. Twenty-something Los Angelenos Joseph/Joey (Eric Stoltz) and Sarah (Meg Tilly) get married, but Joey’s college friend Frank (Craig Sheffer) harbours a hidden love for Sarah. Sarah gradually becomes aware of Frank’s desire for her, but her feelings for him are more ambiguous: during one scene, she tells Frank that the ‘first time we [she and Joey] broke up, I almost went after you’, before kissing him in order to prove that their friendship could have survived their sleeping together (‘See, we’re still friends’, she declares). After one social event, Joey offers Athena (Parker Posey) a lift home; Athena makes it clear that she is willing to sleep with Joey. However, Joey resists Athena’s advances. Meanwhile, Frank and Sarah drive home together, and they end up having sex. Frank and Sarah then struggle to hide their liaison from Joey. What is interesting is the way in which this situation resolves itself, with (spoiler ahoy) Joey discovering Frank and Sarah’s secret, Frank and Sarah seemingly parting ways before rekindling their love for one another, and the lonely Frank left to watch in silence as the happy couple drive away from him.

It’s perhaps ironic that Sleep With Me is largely remembered for Tarantino’s cameo, as his claim that Top Gun is ‘a story about a man struggling with his own sexuality’ could apply to Sleep With Me too. The ménage-a-trois at the centre of the film – between Joey, Sarah and Frank – has homoerotic undertones, as emphasised in the images used to promote the movie (Sheffer, Stoltz and Tilly in bed together) and in several sequences in the film itself. The film opens with Sarah driving the couple’s car, with Joey leaning his head on Frank’s shoulder; in the next shot, the roles are changed, and Sarah has her head rested on Joey’s shoulder whilst he drives. In a later sequence, Joey and Frank are engaged in a poker game with several male friends, and when the pair are the only two players left in the game, they butt heads over the poker table like rutting stags. ‘Do I perceive a homoerotic subtext here?’, one of their friends asks dryly. There is the mere hint of a suggestion that the introspective Frank’s love for Sarah may be a subtle displacement of his desire for the more extrovert Joey. Likewise, Sid’s monologue about Top Gun - interpreted at the time as a narrative-halting non-sequitur - is an act of sexual displacement too, delivered to a fascinated male partygoer after the frustrated Sid fails to engage the attention of a female guest with a similar discussion of pop culture ephemera. However, in exploring this theme, the film shies away from the more explicitly homoerotic territory covered in the similar Gen X movie Threesome (Andrew Fleming, 1994), released the same year as Sleep With Me and focusing on a polysexual ménage-a-trois involving Lara Flynn Boyle, Stephen Baldwin and Josh Charles. Nevertheless, both films look sideways towards Francois Truffaut’s iconic French New Wave film Jules et Jim (1962) for inspiration; this influence is evident throughout Sleep With Me, especially in terms of its French New Wave-via-Tarantino self-referentiality.

Sleep With Me’s script was written by six writers, each writer reputedly contributing a single, discrete sequence revolving around a specific gathering – the wedding of Sarah and Joey, the poker game, the appearance of Nigel’s (Thomas Gibson) novelist mother-in-law Caroline (June Lockhart), the party that closes the film. The problem with this is that at certain points, the film seems to pull in different directions, lacking cohesion. For example, the film opens with a strong scene depicting Joey, Frank and Sarah driving through rural America, suggesting something of a road movie similar to contemporaneous neo-noir pictures such as Delusion (Carl Colpaert) and The Music of Chance (Philip Haas, 1993). However, this is soon abandoned when, after Joey proposes to Sarah, the film shifts gears to focus on Joey and Sarah’s wedding rehearsal; from here, each sequence takes place in a different environment, structured like a series of chamber pieces or a portmanteau film with a linking narrative.

The sequences are separated by Brechtian title cards which disrupt the narrative with dry comments on the action (‘Nothing happened for a few weeks’, one such title card claims, bridging a big ellipsis in the story). These were presumably an addition by Joe Keenan, one of the film’s writers; a similarly witty use of title cards appears in Keenan’s sitcom Frasier (Paramount, 1993-2004). The postmodern technique, characteristic of US ‘indie’ films of the late-1980s and 1990s (eg, Soderbergh’s 1989 sex, lies and videotape), is foregrounded by the use of monochrome videotaped footage, presented in the old Academy ratio of 1.33:1, which is interspersed throughout the film and which first appears during the rehearsal for Joey and Sarah’s wedding, their friends invited by the cameraman to offer comment on their relationship. These fragments are meant to represent filmed interviews with Joey and Sarah’s friends, taken from the point-of-view of Frank as he questions the participants as if they were the subjects in a social scientist’s experiment. In one scene, during an awkward confrontation, the camera is taken from him by Sarah, the gaze unexpectedly returned by its subject. This, along with the clipped, referential dialogue that was popularised by Tarantino and became characteristic of US independent cinema in the early 1990s, means that like many of the 1990s Gen X relationship movies, Sleep With Me has a self-referential air that may irritate some viewers.

The characters are also prone to a spot of navel-gazing that may alienate some members of the audience: during one soiree, Joey talks about sex and philosophy and delivers the mind-blowing assertion that ‘It’s only really just before I blow my wad that I experience what it was like to be born’. In another self-reflexive sequence, in which Nigel’s novelist mother-in-law visits, we are shown her in Nigel’s living room, surrounded by the group of friends, as she complains that ‘One rarely sees characters as old as mine in films’. The young people sit on, listening but clearly uninterested in what she is saying or, in some cases, quietly mocking her. The sequence (perhaps unintentionally) satirises the group of youth oriented ‘indie’ films to which Sleep With Me belongs. It also challenges the audience’s identification with the film’s protagonists: it’s difficult to identify where the audience’s sympathies are supposed to lie, as the Gen X-ers’ treatment of the older woman is so disrespectful – but on the other hand, are we meant to share their disapproval of her complaints about modern culture? Finally, the last line of dialogue suggests that the film aspires to a Bret Easton Ellis-like critique of the ennui experienced by its twenty-something protagonists: Frank is told by one of the partygoers, ‘Do you ever think that we have too much time on our hands? With all the advances we’ve made in extending the human lifespan, that perhaps nature’s cruellest irony is that we get progressively stupider and stupider with each passing generation. I mean, someday we’ll be able to live for 300 years but we won’t be able to sit still for five seconds’. With this, the song that plays over the closing credits (‘Wasted’ by Pere Ubu) tells us we are ‘recklessly throwing time away, breathlessly throwing time away’. However, at this point in the narrative, the comment seems more like a glib, throwaway line; it’s an interesting theme that, within the context of the film, is underdeveloped. The film struggles to find a cohesive approach to its twenty-something protagonists, perhaps due to a case of 'too many cooks'.

The film runs for 82:29 mins (PAL) and is uncut.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, presented here with anamorphic enhancement. As far as I can ascertain, this is the first time the film has been presented in its OAR on the DVD format. The transfer is good, showcasing Andrzej Sekula’s low-key, intimate cinematography – vastly different from his work on the same year’s Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994). Some of the compositions are amazing; the film has a very strong aesthetic that arguably transcends its low-key subject matter.

Audio

The disc contains a two-channel audio track, with subtle surround encoding. There are no problems with the audio track. However, sadly there are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole extra is the film’s US trailer (2:20). The trailer sells the film as a romantic comedy, focused on Sheffer’s jealousy at Stoltz and Tillly’s relationship, describing the movie as ‘the timely story of boys love girl, girl loves boys, and a group of friends who are worried about the bigger issues’. Tarantino’s cameo at the party is foregrounded, as is his Top Gun speech. As the narrator intones, ‘It’s a film ‘about those three little words we all want to hear: “Sleep With Me”’.

Overall

The film is a time capsule to a very different era of romantic comedies. Made in a post-Tarantino context, where ironic, allusive and fractured dialogue became common, Sleep With Me was (and still is) known as the movie in which Tarantino put forward his argument that Top Gun is about Maverick’s struggle with his homosexuality. It’s worth pointing out that Tarantino’s comments about Top Gun seemed to paraphrase an article by cultural critic Mark Simpson, published the same year in Simpson’s book Male Impersonators; Simpson has since said that ‘I’m sure it was just a case of great nerdy minds thinking alike, but the timing was interesting’ (Simpson, quoted in Stevens, 2003: np). Tarantino’s cameo overshadowed the film’s narrative, in both the marketing of the film and its reception. However, at the time Tarantino was still the darling of American independent cinema, and his brief cameo appearance bought Sleep With Me a certain cachet amongst fans of independent movies. Essentially a Gen X-ers Jules et Jim, Sleep With Me was described by Bruce Westbrook, in an article for the Houston Chronicle, as ‘an edgy, dark and audacious romantic comedy’; Westbrook suggested that although ‘Sleep With Me probably will be likened to other Generation X odes, such as Singles and Reality Bites, it's really more of a twentysomething spin on the baby boomers' Big Chill as old friends let their hair down during impolite parties whose bare-all outbursts are like group-therapy sessions’ (Westbrook, 1994: np). The introspective and self-referential dialogue sometimes struggles to say something profound about the lives of the film’s protagonists, and can make the characters difficult to like. Nevertheless, the film provokes a curiously nostalgic feeling for an era in which American cinema could be so introspective (or self-absorbed and narcissistic, depending on your point of view) and relatively low-key. Whilst buried within the subgenre of very similar Gen X romantic comedies, Sleep With Me is a capsule of an era in which popular cinema was undergoing dramatic change; fans of this film will find this DVD release worth purchasing solely due to the presentation of the movie in its original aspect ratio. References: Stevens, Andrew, 2004: ‘3AM Interview: Metrosexuality’. [Online.] http://www.3ammagazine.com/litarchives/2004/jan/interview_mark_simpson.html Westbrook, Bruce, 1994: ‘Speak to me: Comedy blazes direct-to-video path with quality, brutal honesty’. Houston Chronicle. [Online.] http://www.chron.com/CDA/archives/archive.mpl/1995_1257847/speak-to-me-comedy-blazes-direct-to-video-path-wit.html For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|