|

|

Tony Manero

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (22nd January 2012). |

|

The Film

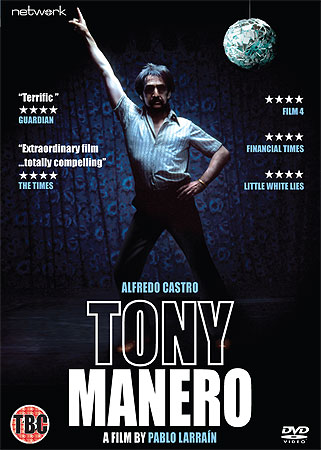

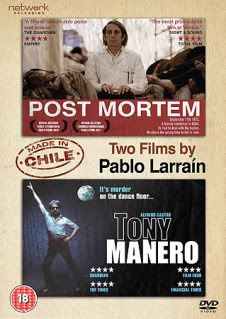

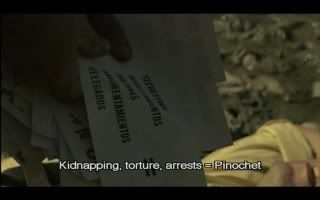

Tony Manero (Pablo Larraín, 2008) Please note that Tony Manero has been released by Network Releasing both separately and as part of a two-disc set entitled Made in Chile: Two Films by Pablo Larraín, accompanied by Larraín’s thematically similar 2010 film Post Mortem.   Winner of Best Film and the Film Critic’s awards at the Turin Film Festival, Tony Manero (Pablo Larraín, 2008) is set in Chile’s capital city Santiago in 1978, against the backdrop of General Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. The film focuses on Raúl Peralta (Alfredo Castro), the 52 year old leader of a low-rent dance troupe who is obsessed with John Badham’s disco-era classic Saturday Night Fever (1977). The film begins and ends with Peralta’s attempts to hawk his John Travolta impersonation on Chilean television, and in between it sketches the narrative of an opportunistic criminal and murderer whose crimes are enabled, if not sanctioned, by the Pinochet regime – a society in which political ‘subversives’ are executed for distributing anti-Pinochet literature, whilst a murderer is allowed to continue his crimes. Peralta’s crimes are set within the context of his attempts to perfect his imitation of Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever, and thus the film is frequently interrupted by dance rehearsals set against the Bee Gees’ ‘You Should Be Dancing’. In Cinema Today: A Conversation with Thirty-Nine Filmmakers from Around the World, Elena Oumano declares that the film is ‘a grim, almost documentary-style “musical” [….] a gritty, terrifying allegory about the spell cast by American pop culture during the dark years of General Augusto Pinochet’s police state’ (Oumano, 2010: 259).  The film opens with a handheld tracking shot that follows Peralta as he walks through the backstage area of a television studio. Outside a sound stage where a programme is being recorded with a live audience, he waits in line, observant and distant from those around him. He attempts to enter the sound stage but is told to wait outside. Asked his name, he announces himself as ‘Tony Manero’. ‘This week it’s Chuck Norris’, a woman exclaims before telling him, ‘Your turn is next week’. Sent to an office to register for the next week’s contest, Peralta declares his profession as ‘this’. ‘This what?’, the woman taking his details asks. ‘Show business’, Peralta responds. After leaving the television studio, Peralta visits a rundown cinema and buys a ticket for Saturday Night Fever. We follow him into the auditorium. As he takes a seat, he mimics Travolta’s onscreen moves and, despite not understanding English, repeats Travolta’s dialogue as it is spoken on screen.  Later, witnessing a fight that takes place outside his flat above the café/bar in which he and his dance troupe work, he sees an elderly woman attacked. Rushing into the street, he helps her. ‘Thank God there are decent people like you’, the elderly woman tells him before inviting him into her home. ‘Do you know that General Pinochet has blue eyes?’, the woman asks Peralta before observing that it’s ‘strange’. Without warning, Peralta attacks the helpless elderly woman and beats her to death. The violence is sudden and unexpected, and after it is over Peralta steals the woman’s small television set; whilst carrying it through the streets, he hides in an alcove from a group of soldiers who are travelling in an open-topped truck. At the café where Peralta’s dance troupe are performing, we are introduced to Peralta’s colleagues: his lover Cony (Amparo Noguera), her daughter Pauli (Paola Lattus) and Pauli’s boyfriend Goyo (Héctor Morales). There, they rehearse their routine to the Bee Gees' ‘You Should Be Dancing’: it’s a routine that is intended to be a pastiche of the show-stopping nightclub sequence in Saturday Night Fever. During the rehearsal, Goyo’s presumed communist sympathies are mocked, and he is told by the café’s owner, Wilma (Elsa Poblete), to ‘Shut up, communist. We are here to work. This is your job’. When Peralta stumbles and falls during the rehearsal – whilst practicing Travolta’s Cossack dance-inspired move – he explodes with rage and smashes up the stage, declaring that the floor is rotten. Admonished by Wilma, who reminds him that ‘We can hardly pay the bills, and you are smashing up the floor’, Peralta storms out of the building, calling Wilma a ‘bitch’. With Cony, he visits a glass warehouse with the intention of buying a high-density glass floor like the underlit dancefloor in the nightclub in Saturday Night Fever. He is told it will cost 75,000 pesos because ‘it’s imported’. However, he’s offered a deal of 60,000 pesos ‘without delivery’. This is still too expensive, and Peralta and Cony leave empty-handed. Instead, Peralta tries to barter with the watchman at a nearby scrapyard, who offers to trade some blocks of high density glass for the television set that Peralta stole from the elderly woman’s home. However, the television will not be enough to buy all of the glass that Peralta needs, the watchman telling him ‘the TV set is not enough [….] Things cost what they cost, not what you want them to. And I say what the price is, not you’. Managing to acquire enough high density glass to pathetically patch the small section of the stage that he smashed, rather than replacing the whole floor with it, Peralta tells Wilma that the underlit glass – now a pale imitation of the dancefloor in Saturday Night Fever’s nightclub – is ‘for the effect’. Wilma attempts to seduce Peralta, telling him that Cony and Pauli are ‘whores’ and asserting, ‘I don’t think you can see the difference between me and them’. She asks Peralta, ‘Once the film [Saturday Night Fever] is out of fashion, do you think they’ll still follow you?’ ‘It’s not fashion’, he retorts angrily. However, Peralta is dismayed when, later, he visits the cinema and asks for a ticket to see Saturday Night Fever only to discover that it’s been taken off and replaced with ‘another film with the same gentleman’ (as the elderly ticket booth attendant tells him), Grease (Randal Kleiser, 1978). In response to this, Peralta quietly murders both of the cinema’s elderly employees – the ticket booth attendant and her husband, the projectionist – stealing what little cash there is in the ticket booth and also taking several film cans containing reels from Saturday Night Fever.  As the evening of Peralta’s appearance in the television lookalike contest draws closer, Raúl and his troupe work on perfecting their routine. However, their work is interrupted when the café is invaded by military police who are seeking Goyo for his part in distributing anti-Pinochet literature. Abandoning his surrogate ‘family’ to the authorities, Peralta manages to escape and makes his way to the television studio. In Themes in Latin American Cinema: A Critical Survey (2011), Keith John Richards locates Tony Manero within the picaresque tradition of Latin American filmmaking – the long-standing tradition of films about rogues, iconoclasts and scoundrels. Suggesting that in comparison with American crime films, Latin American crime pictures ‘offer a divergence, most strikingly through their humanity and believability’, Richards argues that in Latin American cinema crimes ‘are less likely to succeed, go undetected, or be perpetrated without some degree of soul searching, and are committed by rather more than just an anti-hero with a get-rich-quick motive in a film that caters for the public’s taste for violence, luxurious surroundings, and aggressive posturing’ (119). Rather than encouraging identification with roguish anti-heroes, which is what Richards suggests American crime movies tend to do, Latin American crime films usually offer a ‘critical or ironic distance between the positions of filmmaker and protagonist, allowing for some explanation of the latter’s actions and social positions’ (ibid.). They also frequently offer direct ‘social commentary, whether through state involvement or police implication in the crimes depicted, displaying a cross-section or interaction between rich and poor and often a direct encounter between social classes’ (ibid.). Referring specifically to Larraín’s film, Richards argues that ‘[e]ven as scabrous an antihero as the John Travolta-obsessed Raúl in Tony Manero […] has to be seen in the context, albeit far from mitigating, of the desolate inhumanity of Pinochet’s late-1970s Chile where political delinquency, common criminality and slavish cultural imitation are complementary elements’ (ibid.).  Although the topic of Pinochet’s regime is rarely directly mentioned in Tony Manero, reflecting its protagonist Peralta’s apparent lack of interest in politics and his disengagement from the social realities of the society that he lives in, the effects of Pinochet’s military dictatorship are subtly present throughout. Indices of the dictatorship appear at several points in the film: after Peralta has killed his first victim and stolen her television, he hides from a truckload of soldiers who are apparently completely disinterested in his crimes. Later, Peralta watches a group of people, including Goyo, outside his home. He follows one of the men, Jose, and picks up a large rock with the intention of murdering him. Chasing after Jose, Peralta stops when, on a footbridge above a railway line, Jose’s path is blocked by the police. Whilst Peralta hides out of sight, Jose is shot by the two policemen who stopped him, and he is left for dead by a riverbank; the opportunist Peralta steals items from the body, including a necklace and a watch, before discovering that the ‘crime’ for which Jose was callously executed was nothing more than distributing anti-Pinochet flyers. The message is clear: the authorities are more interested in persecuting political ‘subversives’ than tracking down and punishing murderers and thieves like Peralta.  Peralta’s violence is sudden and unexpected. His attack on his first onscreen victim, the elderly widow, is without precedent and completely unsignposted by his behaviour prior to the attack. Like Reno’s (Abel Ferrara) similarly bluntly brutal executions of the derelicts in Ferrara’s 1979 horror film Driller Killer, Peralta’s acts of violence and murder may be interpreted as a response to (or outgrowth of) the poverty of his surroundings. In the first murder scene, without warning Peralta attacks the helpless elderly woman and beats her to death. As the audience barely has time to register Peralta’s actions, his victim doesn’t have time to react. Throughout the moment of violence, Peralta’s expression denotes disconnection and impassivity. The beating is administered below the frame: we don’t see the violence, only his blows raining down on the bottom of the frame. Likewise, the other acts of violence (the police shooting of Jose, Peralta’s murder of the scrapyard dealer) take place offscreen and are disturbing because they are presented in such a matter-of-fact, almost clinical way – which is antithetical to how violence is usually represented in popular cinema. This deadpan, matter-of-fact depiction of murder, and the film’s documentary style – which makes abundant use of handheld tracking shots following Raúl through the streets of Santiago, along with jarring Godard-esque jump cuts – have led to comparisons with John McNaughton’s similarly blackly comic Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) (for example, see Hill, 2009: np).  Like Henry Lee Lucas (Michael Rooker) in McNaughton’s film, Peralta’s violence seems to be psychosexual - linked to his impotence, both socially and sexually. From the outset, Peralta is depicted as a passive voyeur (or, considering the film’s abundant use of tracking shots that depict Raúl walking through the streets of Santiago, a flaneur): during the opening sequence, he is observant and detached amongst the group of men preparing for their appearance on the television show that Peralta hopes will be his route to fame, and at home in his flat he is frequently shown observing the streets outside – this seems to be his preferred method for selecting his victims, including the elderly woman and Jose.  On the other hand, Peralta’s sexual impotence is shown more explicitly, in a sequence in which he and Cony attempt to make love. During foreplay, Cony observes, ‘These people don’t think about the future’. Peralta’s lack of foresight is evidenced in his response, ‘What future?’ ‘Your future. My future, their future’, Cony responds; ‘But I know we’ll make it with the show’, she says. Cony masturbates Peralta before performing fellatio on him. ‘We have to get out of here’, she tells Raúl before reminding him of his increasing age and the distance between him and his idol: ‘Because Tony Manero from the movie will never get old, but you are’. In response to this, Peralta shoves his fingers down Cony’s throat in rage. ‘You’re lifeless. You can’t even get a hard on. It gets swollen, but not hard’, she taunts him: ‘The glass floor is the only thing that turns you on. You’re such a fool. He’s an American. You’re not. You belong here, like the rest of us’. Her attempts to ridicule Peralta and emphasise the disparity between his world and the world of Saturday Night Fever’s Tony Manero ring true, but she ignores the fact that both Raúl and Tony are both proletarian: they are separated by age and nationality but not by class. Later, Peralta’s social and sexual impotence collide when, after his troupe’s performance in Wilma’s establishment, he dances with Pauli whilst Cony looks on and tells him to stop. As Pauli, who has had too much to drink, is sick in the lavatory, Raúl gropes her whilst pretending to offer her support. Afterwards, when they are alone Peralta attempts to seduce Pauli; they engage in foreplay but Pauli eventually casts Raúl aside, preferring to masturbate herself to climax whilst he collapses on the bed and looks on frustratedly. They are interrupted by Cony, who yells at Pauli, ‘You’re going to end up shitting a bastard’. Peralta’s obsession with Saturday Night Fever borders on mania. During his first visit to the cinema, as he enters the auditorium he mimics Travolta’s moves and recites the dialogue, establishing his familiarity with the movie. Cony’s assertion that ‘Tony Manero from the movie will never get old, but you are’ cuts to the quick, and Peralta is soon attempting to regain his youth, and re-establish his resemblance to Travolta’s character, by dyeing his hair. Visiting the cinema again during a later sequence, Raúl intensely watches the sequence from Saturday Night Fever in which Travolta, dressed only in the tightest of underpants, poses in front of a mirror. This famous display of male narcissism is also notable as being one of the few scenes in mainstream Hollywood cinema in which the male body is objectified to such an extreme degree: Chris Jordan (2003) has stated that in this scene, ‘Tony Manero’s narcissistic gaze upon himself is coded as female, though a close-up of his bulging crotch simultaneously offers a blatantly overdetermined construction of masculinity’ (117). Larraín offers similar views of Raúl stripped down to his underwear; although in one sequence, Raúl poses as Tony Manero in front of his own mirror, in the majority of these sequences Peralta is – unlike his idol – shown to be nothing more than a middle-aged man who is slouched in an armchair whilst wearing his underwear. Where Travolta’s semi-nudity signifies his narcissism and virility, Raúl’s nudity is an index of vulnerability and passivity.  Later, in Wilma’s café Peralta ritualistically re-enacts a scene from Saturday Night Fever, flatly reciting Travolta’s famous crucifix speech from the film (‘One day, you look at a crucifix and all you see is a man dying on a cross’) – despite the fact that, as Cony points out, Raúl does not speak or understand English. Chris Jordan has argued that in Saturday Night Fever, ‘the lit, mirror-balled floor [in the 2001 disco] transforms [Travolta’s Tony Manero] from a minimum-wage high school graduate into a celebrity’, and it is perhaps this dream of transformation that Peralta aspires towards (ibid.). Frequently juxtaposing Raúl’s hero worship of Travolta and the use on the soundtrack of the Bee Gee’s ‘You Should Be Dancing’ with both traditional Chilean music and more modern Chilean pop (in one scene, Raúl performs Travolta’s dance to Chilean pop music on the radio), Tony Manero establishes a relationship between the rise of Pinochet’s dictatorship and the growth of Hollywood cinema (post-Jaws) as escapist entertainment – although it’s perhaps worth reflecting on the fact that despite its reputation as an escapist glitterball-like fantasy, Saturday Night Fever was at least in part a fairly gritty look at the lives of working-class New Yorkers. Raúl’s slavish attempts to emulate his American idol seems like a fairly direct allegory of Pinochet’s relationship with the United States: during Pinochet’s dictatorship, the US famously restored aid that had been withdrawn during the era of Pinochet’s predecessor, the democratically-elected Salvador Allende, whose presidency was unpopular with Richard Nixon’s government due to Allende’s Marxist leanings.  The film establishes a dialectical relationship between pro-Pinochet and anti-Pinochet beliefs. From his first scene in Wilma’s café, Goyo is criticised for his anti-Pinochet beliefs and communist leanings. In a much later sequence, Pauli returns to the café during a torrential rainstorm. She reveals that the streets are flooded, and Goyo is helping people to return home whilst the army is doing nothing to assist the civilians. ‘Things are finally working in this country’, the pro-Pinochet Wilma asserts. However, despite her vocal support of Pinochet’s regime, Wilma is still victimised by the police when they enter the café looking for Pauli and Goyo – due to their associations with Jose. Somewhere in the middle is Raúl, an apparently apolitical man whose opportunistic crimes and acts of violence are enabled, if not sanctioned, by the Pinochet regime. Raúl’s first elderly victim’s ambiguous statement about Pinochet’s blue eyes (which she calls ‘strange’) seems to be intended as an index of her support for him, but it’s also worth noting that Chilean novelist Ariel Dorfman (writer of the play Death and the Maiden, filmed by Roman Polanski in 1994) suggested that those who supported Pinochet were often taken in by his appearance. In his book Exorcising Terror (2002), Dorfman tells a story of how one of his wife’s friends expressed support for Pinochet. ‘But why? [….] What about the dead, the executed, the exiled?’, Dorfman asked her. ‘Oh [….] he doesn’t know about any of that. Just look at him, our Tata [Chilean colloquialism for grandfather], he has such beautiful blue eyes’ (95-6). The film is uncut and runs for 93:06 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1, with anamorphic enhancement. This seems to be its intended aspect ratio.

The film has a documentary-style aesthetic reminiscent of New Wave cinemas: much of the film is shot in grungy environments, making copious use of a handheld camera and jump cuts. The presentation of the film is more than acceptable, but blown up on large displays viewers may notice some artifacting here and there – but certainly nothing that should spoil one’s enjoyment of the film.

Audio

The disc offers the choice of a Dolby Digital 5.1 mix or a two-channel stereo mix, both of which are clear and free of any issues. The 5.1 mix contains some subtle surround encoding, in line with the naturalistic approach that the film adopts: it’s certainly not a ‘showy’ surround track. English subtitles are optional.

Extras

Bonus trailers (play on start-up, skippable): Rumba, After School Q&A with Alfredo Castro (16:09). In this interview, conducted in April, 2009 at the ICA in London, Alfredo Castro (who plays the film’s protagonist) is interviewed onstage by Maria Delgado. The interview is conducted in English. They discuss Larraín’s inspiration for the film, the changes through which the script went and Castro’s background as a theatre actor. Castro talks about the film’s setting against the backdrop of Pinochet’s regime, suggesting that the film is about a ‘man [Raúl] without morality, without political ideas, not supporting Pinochet or being against Pinochet’, suggesting he is ‘a mirror of a part of Chilean society at that time’, reflecting the fact that most Chileans professed ignorance of the brutality of Pinochet’s regime (‘most people of Chile say they didn’t know that Pinochet was killing people’). He describes Raúl as ‘this man without morality, a sort of animal, without political ideas, without morality, […] illiterate; we found very interesting, this […] social class […] a marginalised part of society’. Castro reveals that there were no rehearsals and claims that Larraín told him ‘not to act, just “be”’. He spent two months preparing the choreography for Raúl’s dance. Delgado suggests that Raúl is ‘split between this Western imperialist ideal’, represented through his desire to become Tony Manero in Saturday Night Fever, and his own cultural background, signified through the ways in which when we see him at home in his apartment he listens to traditional Chilean music. Castro suggests that during the late-1970s, European films and films ‘with a message’ were forbidden in Chile, and ‘only American films, just to make people don’t think about the political process of living there, and all this killing and horror we lived [sic]’. Castro and Delgado discuss the parallels between Raúl and Pinochet himself, with Delgado suggesting that Raúl’s amorality and uniform (his appropriation of Travolta’s dress in Saturday Night Fever) reflects Pinochet’s love of grand uniforms. Castro discusses his working relationship with the other actors, who he says he has worked with ‘for a long time’. He also discusses his relationship with Larraín, with whom he has now worked on three films. Their first film together was, in Castro’s words, ‘a failure’. Delgado and Castro discuss the film’s visual style and the use of the handheld camera. Castro also discusses his feelings towards Raúl, who he describes as ‘just a man who lived at that time of history’, offering a criticism of ‘pro-active American heroes’ and suggesting, ‘I just like people: human beings’. Trailer (2:42).

Overall

Parodies of Travolta’s persona (and dance) in Saturday Night Fever have been ten-a-penny since the film’s original release, most notably in Airplane! (David Zucker & Jim Abrams, 1980). As an iconic picture of the disco era, Saturday Night Fever has acquired a reputation as a camp film. However, here Larraín and his actors turn the dance into a closely-studied, twitchy ballet, Peralta’s performance of it almost mechanical, his face fixed into a scowl of concentration rather than the expression of joy and freedom that Fever’s Tony Manero represented. Something that was once camp is, in Larraín’s hands, recreated as seedy and unsettling.  Aided by an amazingly intense performance from Castro in the lead role, and a final sequence that ends on an ambiguous and thought-provoking note, Tony Manero is a dark and naturalistic examination of Chile under Pinochet; its study of a totalitarian society is almost Orwellian in its depiction of how an authoritarian system can win the consent of at least some of its populace. On the other hand, its study of sad and unfulfilled lives should hold resonance even for viewers who may not be interested in the film’s immediate social context. This is arguably one of the best films of the 2000s and comes with a strong recommendation. References: Dorfman, Ariel, 2002: Exorcising Terror: The Incredible, Unending Trial of General Augusto Pinochet. Seven Stories Press Hill, Lee, 2009: ‘The Dance Macabre of Tony Manero’. [Online.] http://www.vertigomagazine.co.uk/showarticle.php?sel=bac&siz=1&id=1139 Jordan, Chris, 2003: Movies and the Reagan Presidency: Success and Ethics. Greenwood Publishing Group Oumano, Elena, 2010: Cinema Today: A Conversation with Thirty-Nine Filmmakers from Around the World. Rutgers University Press Richards, Keith John, 2011: Themes in Latin American Cinema: A Critical Survey. London: McFarland For more information, please visit the homepage of Network. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|