|

|

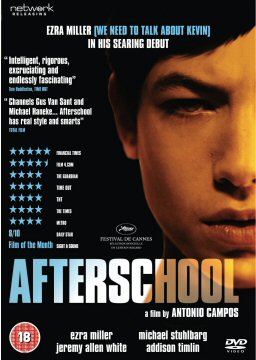

Afterschool

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th February 2012). |

|

The Film

Afterschool (Antonio Campos, 2008) Films set in schools and other places of learning have a long heritage.  Although films set in and around educational institutions were popular in the 1930s, especially with vaudeville/variety hall comedians (for example, the Will Hay films Boys Will Be Boys, 1935, and The Ghost of St Michaels, 1941, and Laurel and Hardy’s A Chump at Oxford, 1940), the ‘daddio’ of the modern school drama is arguably Richard Brooks’ Blackboard Jungle (1955), adapted from Evan Hunter’s (aka Ed McBain) 1954 novel and, alongside Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Laslo Benedek’s The Wild One (1953), part of the wave of films produced in Hollywood during the 1950s with the aim of appealing to the newly-defined teenage audience. In American cinema, the school-set film acquired new popularity in the 1980s and became associated with the ‘Brat Pack’: films like Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), John Hughes’ The Breakfast Club (1985) and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (Hughes, 1986) used schools as the site for their ‘coming of age’ narratives. By and large, these films – especially those of John Hughes – have been labelled as ‘neoconservative’ and driven by nostalgia (De Vaney, 2002: 204). On the other hand, at the end of the 1980s Heathers (Michael Lehmann, 1988) offered a blackly comic deconstruction of 1980s high school films by ‘tak[ing] the stereotypes with which The Breakfast Club plays – the jock, the cheerleader – and show[ing] them as opportunities for malicious behaviour rather than mere social roles’ (Kaveney, 2006: 50). In Heathers, after one of the ‘Heathers’ – the most popular girls in the school – dies, when one of the less popular girls in the school commits suicide it is considered to be an attempt to imitate the school’s dominant clique; ‘Heathers thus uses its dark comedy to exploit the ignorance and conceit of these popular students, who achieve their greatest popularity through death’ (Shary, 2002: 64). Although films set in and around educational institutions were popular in the 1930s, especially with vaudeville/variety hall comedians (for example, the Will Hay films Boys Will Be Boys, 1935, and The Ghost of St Michaels, 1941, and Laurel and Hardy’s A Chump at Oxford, 1940), the ‘daddio’ of the modern school drama is arguably Richard Brooks’ Blackboard Jungle (1955), adapted from Evan Hunter’s (aka Ed McBain) 1954 novel and, alongside Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Laslo Benedek’s The Wild One (1953), part of the wave of films produced in Hollywood during the 1950s with the aim of appealing to the newly-defined teenage audience. In American cinema, the school-set film acquired new popularity in the 1980s and became associated with the ‘Brat Pack’: films like Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), John Hughes’ The Breakfast Club (1985) and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (Hughes, 1986) used schools as the site for their ‘coming of age’ narratives. By and large, these films – especially those of John Hughes – have been labelled as ‘neoconservative’ and driven by nostalgia (De Vaney, 2002: 204). On the other hand, at the end of the 1980s Heathers (Michael Lehmann, 1988) offered a blackly comic deconstruction of 1980s high school films by ‘tak[ing] the stereotypes with which The Breakfast Club plays – the jock, the cheerleader – and show[ing] them as opportunities for malicious behaviour rather than mere social roles’ (Kaveney, 2006: 50). In Heathers, after one of the ‘Heathers’ – the most popular girls in the school – dies, when one of the less popular girls in the school commits suicide it is considered to be an attempt to imitate the school’s dominant clique; ‘Heathers thus uses its dark comedy to exploit the ignorance and conceit of these popular students, who achieve their greatest popularity through death’ (Shary, 2002: 64).

Like Heathers, Afterschool, the debut feature of young director Antonio Campos, focuses on the death of a popular student – or, in the case of Campos’ film, a pair of twins, the Talbots. Also like Heathers, Afterschool focuses on the destructive and violent side(s) of school life; and like Jean Vigo’s subversive Zéro de conduite (1933), Lindsay Anderson’s If…. and Ringo Lam’s School on Fire (or Jonathan Coe’s novel The Rotters’ Club, 2001), Afterschool could also be said to use its school setting symbolically, functioning as an allegory of wider social anxieties. In an article about Peter Weir’s prep school-focused Dead Poets Society (1989), the Chicago Reader’s Kurt Jacobsen declared that in Zéro de conduite and If…., ‘Vigo and Anderson treat school settings not only as crucibles in which to study the courage and character of youth in conflict with imperious pedants but also as symbolic battlefields where wider social issues--inequality, bigotry, militarism, etc--come nakedly into play. Ignore the latter and all you have are tales of the travails of wealthy brats wallowing in standard teenage angst amid their pompous circumstances’ (1989: np). Through Afterschool’s focus on a traumatic incident (the deaths of two popular female students) and the subsequent tightening of personal freedoms, it’s difficult not to see the film as using its prep school setting as a similar ‘symbolic battlefield’ through which Campos explores post-9/11 anxieties in American society.  Afterschool focuses on Internet-addicted teenager Rob (Ezra Miller), a student at a seemingly prestigious East Coast prep school. Rob shares a dorm room with Dave (Jeremy Allen White), who is part of the school’s underground drug culture. Electing to take a video production class (instead of sports), Rob is thrown together with the attractive Amy (Addison Timlin), and despite Rob’s apparent disconnection from the world around him, he and Amy soon become boyfriend and girlfriend. However, whilst shooting B-roll footage for the class documentary, Rob captures the death (by accidental drug overdose) of two of the most popular girls in school. Rob is encouraged to visit the school counsellor, Mr Virgil (Gary Wilmes), and is given the task of producing a memorial film about the two girls who died. Meanwhile, the culture of the school becomes increasingly repressive as the principal introduces random room searches and drug tests. When Rob turns in his memorial video, an oddly-constructed little film that is either intentionally abstract or simply crudely-assembled, the principal balks and has the film re-edited into a more conventional memorial piece. However, alternate footage of the girls’ deaths (other than that shot by Rob) begins to circulate, recorded with the camera on a mobile telephone and apparently showing that an emotionless Rob either enabled or, worse, hastened the passing of one of the twins. Afterschool focuses on Internet-addicted teenager Rob (Ezra Miller), a student at a seemingly prestigious East Coast prep school. Rob shares a dorm room with Dave (Jeremy Allen White), who is part of the school’s underground drug culture. Electing to take a video production class (instead of sports), Rob is thrown together with the attractive Amy (Addison Timlin), and despite Rob’s apparent disconnection from the world around him, he and Amy soon become boyfriend and girlfriend. However, whilst shooting B-roll footage for the class documentary, Rob captures the death (by accidental drug overdose) of two of the most popular girls in school. Rob is encouraged to visit the school counsellor, Mr Virgil (Gary Wilmes), and is given the task of producing a memorial film about the two girls who died. Meanwhile, the culture of the school becomes increasingly repressive as the principal introduces random room searches and drug tests. When Rob turns in his memorial video, an oddly-constructed little film that is either intentionally abstract or simply crudely-assembled, the principal balks and has the film re-edited into a more conventional memorial piece. However, alternate footage of the girls’ deaths (other than that shot by Rob) begins to circulate, recorded with the camera on a mobile telephone and apparently showing that an emotionless Rob either enabled or, worse, hastened the passing of one of the twins.

Drawing parallels with the work of J G Ballard, from its opening moments Afterschool explores the ‘death of affect’: the film’s opening montage of Internet video clips encompasses the familiar iconography of Internet video-sharing sites, including brief footage of a baby laughing hysterically, the slapstick delights of someone falling from their bicycle and the surreal spectacle of a cat playing the piano. Such innocuous material is incorporated into the montage alongside the widely-circulated mobile telephone video recording of the execution of Saddam Hussein and various images from the war in Iraq. Following this, the audience is presented with a clip from ‘nastycumholes.com’ – shot by Campos using the iconography of ‘gonzo’ pornography – which shows an increasingly scared young woman in her underwear being verbally, and then physically, abused by the man who is holding the camera: he taunts her by asking her if she is ‘scared mom and dad will find out [she] is a whore’ before holding her by her throat and pretending to choke her. We are then shown Rob in his darkened dorm room, apparently masturbating to the clip. It’s a stark opening in which misogynistic Internet pornography is equated with ‘mondo’ death footage and the usual cute/comical clips that find their way onto video sharing websites; it communicates the flattening of affect amongst the Youtube generation, for whom everything is ready for consumption regardless of its original meaning, context or content. Drawing parallels with the work of J G Ballard, from its opening moments Afterschool explores the ‘death of affect’: the film’s opening montage of Internet video clips encompasses the familiar iconography of Internet video-sharing sites, including brief footage of a baby laughing hysterically, the slapstick delights of someone falling from their bicycle and the surreal spectacle of a cat playing the piano. Such innocuous material is incorporated into the montage alongside the widely-circulated mobile telephone video recording of the execution of Saddam Hussein and various images from the war in Iraq. Following this, the audience is presented with a clip from ‘nastycumholes.com’ – shot by Campos using the iconography of ‘gonzo’ pornography – which shows an increasingly scared young woman in her underwear being verbally, and then physically, abused by the man who is holding the camera: he taunts her by asking her if she is ‘scared mom and dad will find out [she] is a whore’ before holding her by her throat and pretending to choke her. We are then shown Rob in his darkened dorm room, apparently masturbating to the clip. It’s a stark opening in which misogynistic Internet pornography is equated with ‘mondo’ death footage and the usual cute/comical clips that find their way onto video sharing websites; it communicates the flattening of affect amongst the Youtube generation, for whom everything is ready for consumption regardless of its original meaning, context or content.

Skirting close to being preachy, Campos shows us that Rob’s exposure to violent pornography impacts on his behaviour and his understanding of human relationships. When Rob is in conversation with the school counsellor, Mr Virgil, he states that he ‘used to really like videos, but I might be getting tired of them’. ‘You mean, like movies?’ Virgil asks. ‘No, just short clips [….] Just like little video clips of things that seem real, usually just like a cat or baby doing something funny, or something violent’, Rob tells Virgil. Virgil asks Rob if he likes porn. Rob tells him he does. ‘There are no real moments in porn, I can tell you that’, Virgil informs him. Referring obliquely to the NastyCumHoles website, Rob tells Virgil about this ‘guy who never shows his face [….] He just gets them [the girls on the site] pretty scared’. When he and Amy are given a camera to record ‘pick up’ shots for the documentary his class has been told to make, he re-enacts what he saw on the clip from NastyCumHoles, grabbing Amy by the throat until, uncomfortable, she protests ‘What, are you trying to strangle me to death? What are you doing?’ This comes after Rob and Amy have been flirting, and Campos seems to be highlighting the effect that Rob’s exposure to more extreme forms of Internet pornography has had upon his view of sexuality. The deaths of the twins due to their dabbling in the school’s underground drugs scene, and the film’s exploration of the death of affect, develops in parallel with the film’s suggestion that prescription medications (presumably anti-depressants) are so common amongst the students that they are met with nonchalance.  Early in the film, Rob calls his mother on the telephone and tells her that he is afraid none of the students like him. Every time he tries to express himself, his mother cuts him off mid-sentence, demanding that he ‘talk about something pleasant’. ‘I think I’m not a good person’, Rob tells his mother. The conversation on the phone is filmed in a similar way to Travis Bickle’s (Robert De Niro) call to Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976): like Bickle, Rob is positioned in a doorway, wandering in and out of frame as he talks – much as the camera pans away from Travis in Taxi Driver, as if it is too afraid to show Travis’ pain whilst Betsy rejects him via the telephone. During the conversation, Rob’s mother suggests that he see the school’s counsellor and request to be given medication. Shortly after, we see lines of students waiting outside the nurse’s room for medication; and later, the suggestion that a significant number of the students are also on prescription medication is raised nonchalantly by the principal. In assembly after the deaths of the twins, the principal asserts that the school will begin random room searches and drug testing, declaring that ‘Anyone in possession of alcohol or drugs, besides those administered to you by the nurse, will be expelled’. Early in the film, Rob calls his mother on the telephone and tells her that he is afraid none of the students like him. Every time he tries to express himself, his mother cuts him off mid-sentence, demanding that he ‘talk about something pleasant’. ‘I think I’m not a good person’, Rob tells his mother. The conversation on the phone is filmed in a similar way to Travis Bickle’s (Robert De Niro) call to Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976): like Bickle, Rob is positioned in a doorway, wandering in and out of frame as he talks – much as the camera pans away from Travis in Taxi Driver, as if it is too afraid to show Travis’ pain whilst Betsy rejects him via the telephone. During the conversation, Rob’s mother suggests that he see the school’s counsellor and request to be given medication. Shortly after, we see lines of students waiting outside the nurse’s room for medication; and later, the suggestion that a significant number of the students are also on prescription medication is raised nonchalantly by the principal. In assembly after the deaths of the twins, the principal asserts that the school will begin random room searches and drug testing, declaring that ‘Anyone in possession of alcohol or drugs, besides those administered to you by the nurse, will be expelled’. Towards the end of the film, seemingly in a desperate attempt to waken himself from his zombified/medicated state, Rob repeatedly slaps himself across the face in front of his computer, before opening his mouth in a silent scream – an image that was used in much of the film’s promotional material. Towards the end of the film, seemingly in a desperate attempt to waken himself from his zombified/medicated state, Rob repeatedly slaps himself across the face in front of his computer, before opening his mouth in a silent scream – an image that was used in much of the film’s promotional material.

Campos also suggests that the principal and other members of the school staff were complicit in the deaths of the girls, through turning a blind eye to the underground drug culture that the presence of Rob’s roommate Dave underscores. During a conversation with Mr Virgil, Rob discovers Virgil knew that both of the twins were taking drugs and informed the principal, who failed to take action: Virgil asserts that the school told ‘me they didn’t want to hear it, that the Talbots were too important to the school and […] they weren’t worried about it. Nothing you can do, nothing I can do’. Despite his alienated state and lack of affect, Rob seems to be the only character who is interested in taking some form of action, and when he believes that Dave may have been instrumental in giving the Talbot girls the drugs that killed them, Rob becomes embroiled in a physical fight with his roommate. During the fight, Rob yells ‘You killed them’; and after the fight has been broken up, Rob is questioned about this by the principal, who reveals that nobody knows where the girls bought the drugs, stating simply that ‘the truth is, Rob, we all kind of gave the girls those drugs that day. Do you see, it’s not just one person’s fault, Rob: it’s everyone’s’. Campos makes interesting use of the video footage shot by Rob. Inserted, window-boxed, into the film, we are shown footage from the perspective of Rob’s camera (as he and Amy learn how to use it, as their relationship develops and Rob coerces Amy into sleeping with him, as he accidentally records the deaths of the Talbot twins, and as he makes his memorial video). In the first instance of this, we are only made aware that we are watching Rob’s video when it rewinds onscreen – like the opening playback of a tape in Michael Haneke’s obtuse thriller Hidden (2005), which only at the end of the titles sequence lets the audience know that they are watching a tape that, within the film’s diegesis, is also being viewed by its protagonists (Daniel Auteuil and Juliette Binoche).  After Rob records the deaths of the Talbot twins, we are only made aware that we are watching it simultaneously with the characters in the narrative when the camera slowly pans away from a video monitor to reveal Rob being questioned by a detective who is investigating the twins’ deaths. In such sequences, Campos’ postmodern ‘toying’ with the medium, and his mixing of several diegetic levels, brings to mind Michael Haneke’s films; and Rob’s disaffected attachment to video violence specifically recalls the protagonist of Haneke’s film Benny’s Video (1993). Rob’s recording of the deaths of the twins could be compared to the footage of the slaughter of a pig that opens Benny’s Video. Both sequences arguably require the viewer ‘to adjust the frame of reference on several ontological levels: (1) this video is a recording of a prior event, because it is; (2) watched and manipulated by somebody else’, and in both cases the footage is replayed obsessively, raising ethical issues due to the ‘aestheticisation’ of death (Speck, 2010: 82). Like Benny (Arno Frisch) in Benny’s Video, the disaffected Rob in Afterschool could be said to represent ‘moral emptiness [as] an effect of technology, the technology of the video image’ rather than the ‘result of any social or historical circumstance’ (Hediger, 2010: 104). In this sense, both filmmakers could be argued to offer what Hediger refers to as ‘a techno-Hegelian explanation of moral decline’ (ibid.). After Rob records the deaths of the Talbot twins, we are only made aware that we are watching it simultaneously with the characters in the narrative when the camera slowly pans away from a video monitor to reveal Rob being questioned by a detective who is investigating the twins’ deaths. In such sequences, Campos’ postmodern ‘toying’ with the medium, and his mixing of several diegetic levels, brings to mind Michael Haneke’s films; and Rob’s disaffected attachment to video violence specifically recalls the protagonist of Haneke’s film Benny’s Video (1993). Rob’s recording of the deaths of the twins could be compared to the footage of the slaughter of a pig that opens Benny’s Video. Both sequences arguably require the viewer ‘to adjust the frame of reference on several ontological levels: (1) this video is a recording of a prior event, because it is; (2) watched and manipulated by somebody else’, and in both cases the footage is replayed obsessively, raising ethical issues due to the ‘aestheticisation’ of death (Speck, 2010: 82). Like Benny (Arno Frisch) in Benny’s Video, the disaffected Rob in Afterschool could be said to represent ‘moral emptiness [as] an effect of technology, the technology of the video image’ rather than the ‘result of any social or historical circumstance’ (Hediger, 2010: 104). In this sense, both filmmakers could be argued to offer what Hediger refers to as ‘a techno-Hegelian explanation of moral decline’ (ibid.).

Rob’s finished version of his memorial video is an unusual, poetic film that, through its abrupt and unfocused interviews, communicates the school population’s honest reaction to the deaths of the Talbot twins – not necessarily a stereotypical response to grief, with a good number of the interviewees admitting that they didn’t know the Talbots in person. Rob’s interviews show the subjects in the moments when they aren’t performing for the camera – whilst they are processing his questions and thinking of unprepared responses to them – and his fascination with the pornographic Internet clip (and his re-enactment of it with Amy and, later, with one of the Talbot twins) perhaps suggests that its appeal for Rob is in the way in which the performer’s ‘mask’ slips when the videographer’s behaviour turns potentially violent. After the memorial video has finished, the principal declares angrily, ‘I’m no editor, but I can safely say that was the worst thing I’ve ever seen. You didn’t even have music’ – reminding us that Campos’ film is similar in style to Rob’s video, even down to the fact that Afterschool features no music. Later, we see the official, re-edited version of Rob’s video when it is shown to the whole school: it’s cloyingly sentimental and accompanied by piano music, foregrounding Afterschool’s status as an almost allegorical film about the altering and re-editing of reality in the aftermath of a tragedy that chimes with the post-9/11 world. Rob’s finished version of his memorial video is an unusual, poetic film that, through its abrupt and unfocused interviews, communicates the school population’s honest reaction to the deaths of the Talbot twins – not necessarily a stereotypical response to grief, with a good number of the interviewees admitting that they didn’t know the Talbots in person. Rob’s interviews show the subjects in the moments when they aren’t performing for the camera – whilst they are processing his questions and thinking of unprepared responses to them – and his fascination with the pornographic Internet clip (and his re-enactment of it with Amy and, later, with one of the Talbot twins) perhaps suggests that its appeal for Rob is in the way in which the performer’s ‘mask’ slips when the videographer’s behaviour turns potentially violent. After the memorial video has finished, the principal declares angrily, ‘I’m no editor, but I can safely say that was the worst thing I’ve ever seen. You didn’t even have music’ – reminding us that Campos’ film is similar in style to Rob’s video, even down to the fact that Afterschool features no music. Later, we see the official, re-edited version of Rob’s video when it is shown to the whole school: it’s cloyingly sentimental and accompanied by piano music, foregrounding Afterschool’s status as an almost allegorical film about the altering and re-editing of reality in the aftermath of a tragedy that chimes with the post-9/11 world.

The film runs for 102:20 mins (PAL).  Please see Network Releasing’s syndicated interview with Campos, which can be found here.

Video

Afterschool is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, with anamorphic enhancement. It’s a clean, crisp image. The film itself has a strange, distancing aesthetic, with Campos preferring to shoot most scenes with unusual and obtuse framing – faces bisected by the frame, only the actors’ torsos in shot. It’s a technique that’s clearly meant to signify the alienation of Rob but may prove to be infuriating for some viewers. He also tends to ape the static, observant camerawork of Haneke.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track (in English). This is clean and problem free. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Extras include: Deleted Scenes (53:12). Almost an hour’s worth of deleted scenes and scene fragments, some of which are minor extensions to scenes that exist in the finished film whilst others are alternate takes. Some are sequences that don’t exist in the finished film at all, including scenes showing Rob in other classes. The ‘raw’ audio in some of these scenes can make the dialogue difficult to decipher. (All deleted scenes are presented in non-anamorphic 2.35:1.) Mobile Phone Videos (3:34). These are unedited clips of the mobile phone videos shown in the film, including Rob’s fight with Dave and the alternate angle of the death of the twins. Teacher Testimonials (26:08). These testimonials from the teachers shown in the film were presumably filmed with the intention that they may form part of Rob’s documentary about the twins. New York Film Festival Trailer (1:16) . Theatrical Trailer (2:03), framed by Rob’s silent scream and containing quotes comparing the film to Asian cinema and the work of Michael Haneke. An image gallery (3:24) containing behind-the-scenes images from the production of the film. Bonus trailers (which play on disc start-up and are skippable) for other releases by Network Releasing: Tony Manero, Rumba and Made in Jamaica.

Overall

Afterschool is an interesting and ambitious indie flick that tackles some big issues but sometimes struggles to make its point. Its criticisms of the Youtube generation, and the effects that technology is having on us, may be somewhat accurate. However, like the work of Michael Haneke (whose films seem to be a major reference point for much of this picture), Afterschool sometimes comes across as preachy and slightly condescending: for example, the film’s suggestion that Rob’s attempts to mimic the aggressive sexuality he sees on NastyCumHoles leads firstly to his abuse of Amy, and then to the death of one of the Talbot twins, is perhaps a little mealy-mouthed. The film has an interesting aesthetic, although the use of obtuse framing may annoy some viewers. Regardless of whether or not it is wholly successful at hitting the targets at which it aims, Afterschool is a thought-provoking picture that, in its symbolic/abstract depiction of school life, has much more in common with the darkly subversive school-set films such as Zéro de conduite, If…. and School on Fire than with the dominant nostalgia-tinged depiction of school life that is associated with American cinema. References: De Vaney, Anne, 2002: ‘Pretty in Pink? John Hughes Reinscribes Daddy’s Girl in Homes and Schools’. In: Pomerace, Murray (ed), 2002: Sugar, Spice, and Everything Nice: Cinemas of Girlhood. Wayne State University Press: 201-16 Hediger, Vinzenz, 2010: ‘Infections Images: Haneke, Cameron, Egoyan, and the Dueling Epistemologies of Video and Film’. In: Grundmann, Roy (ed), 2010: A Companion to Michael Haneke. London: Wiley & Sons: 91-112 Jacobsen, Kurt, 1989: ‘Preppie’s Progress’. Chicago Reader. [Online.] http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/preppies-progress/Content?oid=873959 Kaveney, Roz, 2006: Teen Dreams: Reading Teen Film From ‘Heathers’ to ‘Veronica Mars’. London: I B Tauris Shary, Timothy, 2002: Generation Multiplex: The Image of Youth in Contemporary American Cinema. University of Texas Press Speck, Oliver C, 2010: Funny Frames: The Filmic Concepts of Michael Haneke. London: Continuum Publishing For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|