|

|

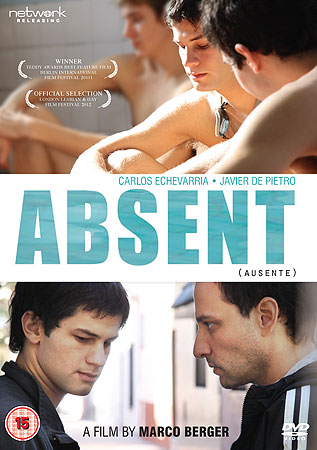

Absent AKA Ausente

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (8th April 2012). |

|

The Film

Absent/Ausente (Marco Berger, 2011)  The second feature from Argentinian director Marco Berger, Ausente (Absent, 2011) carries on the themes introduced in Berger’s debut Plan B (2010), which has also been released on DVD by Network (please see our review here). Plan B offered a subversive look at conventional romantic dramas, focusing on two ostensibly straight men who develop a deep romantic love for one another. Likewise, Absent also explores the malleability of male sexuality. The second feature from Argentinian director Marco Berger, Ausente (Absent, 2011) carries on the themes introduced in Berger’s debut Plan B (2010), which has also been released on DVD by Network (please see our review here). Plan B offered a subversive look at conventional romantic dramas, focusing on two ostensibly straight men who develop a deep romantic love for one another. Likewise, Absent also explores the malleability of male sexuality.

The film focuses on the relationship between Sebastián (Carlos Echevarría), a teacher, and sixteen year old student Martin Blanco (Javier De Pietro). Sebastián finds himself placed in an awkward situation when, one day after class, he offers to take Martin to an appointment with his doctor. Martin manipulates the situation, subtly railroading Sebastián into allowing Martin to spend the night in Sebastián’s flat. This causes problems between Sebastián and his girlfriend Mariana (Antonella Costa), who over the telephone advises Sebastián to hide the CDs in his bedroom because she believes that the boy is intent on stealing. However, Sebastián leaps to Martin’s defense, telling Mariana that the boy is ‘a very easy going kid’. Nevertheless, wary of what people might say, Sebastián also asks Mariana to stay the night; she refuses.  During the evening, the smitten Martin spies on Sebastián as he showers; at night, Blanco surreptitiously creeps into the sleeping Sebastián’s bedroom, pulls back the covers of his bed and begins to put his hand up Sebastián’s shorts. Sebastián stirs, and Martin leaves the room before he awakens. During the evening, the smitten Martin spies on Sebastián as he showers; at night, Blanco surreptitiously creeps into the sleeping Sebastián’s bedroom, pulls back the covers of his bed and begins to put his hand up Sebastián’s shorts. Sebastián stirs, and Martin leaves the room before he awakens.

At work the next day, Sebastián overhears a conversation between two other members of staff. The conversation focuses on a student – presumably Blanco – who failed to return home the previous night, leading his parents to involve the police despite the boy’s claims that he was staying with a friend. Later, Sebastián finds it impossible to tell Mariana about Martin’s brief stay in the flat: when he attempts to do so, Mariana refuses to listen, instead offloading her own concerns to him. Via a note placed on his car, Sebastián discovers that Martin engineered the events leading up to Sebastián’s decision to allow Martin to spend the night at his flat. Realising he has been manipulated by the young man, Sebastián confronts Martin, who confesses that he believed that if he ‘was at your place, something could happen’. ‘Something like what?’, Sebastián asks angrily, slapping Martin. ‘Report me, and see who loses out’, Martin threatens. Shortly after, Sebastián discovers – once again through overhearing a conversation between two other members of staff – that one of the students has died after falling from the roof of the school in which Sebastián works. Correctly believing the deceased student to be Martin, Sebastián is forced to confront his guilt surrounding his angry reaction to the young man’s desire for him.  The film opens with a series of disconnected shots of a male body, later revealed to be that of Martin as he undergoes a medical examination. Close-ups of his toes, his face, lips and nose all establish the theme of voyeurism, and the objectification of the male body, that is carried throughout the first half of the film. Shortly after this opening sequence, Martin will be depicted voyeuristically watching Sebastián in the changing rooms at the school; and when Sebastián allows Martin to spend the night in his flat, the audience is briefly presented with the image of Sebastián showering – presented via a point-of-view shot from Martin’s perspective. Throughout, the knowing and sexually confident Martin is shown to be in control of the gaze, his lustful looks – directed towards Sebastián – establishing his power and control of the situation. Whilst the general perception of films about student-teacher relationships might suggest that the pictures usually represent the teacher as a Clare Quilty-esque exploiter of youth and innocence, the reality is far more complex: films about student-teacher romances range from those that focus on infatuation and unrequited love (To Sir, With Love, James Clavell, 1967; Summer School, Carl Reiner, 1987) to those that depict the student as a femme fatale who lures a teacher to his/her doom (Election, Alexander Payne, 1999; Wild Things, John McNaughton, 1998). For at least a portion of its running time, Ausente seems to conform to the latter group of films, with Martin positioned as a ‘homme fatale’ who ensnares Sebastián and encourages him to question his own sexuality. The film differs from most films about student-teacher relationships through its focus on gay sexuality. Berger has claimed that despite its focus on the desire between student and teacher, Ausente is most definitely not about ‘abuse, because it’s not a film about abuse from an adult to a boy. It’s [about] a boy that knows about this [concept of] abuse but [is] playing with that because he is full of desire’ (FirstPost, 2011). The film opens with a series of disconnected shots of a male body, later revealed to be that of Martin as he undergoes a medical examination. Close-ups of his toes, his face, lips and nose all establish the theme of voyeurism, and the objectification of the male body, that is carried throughout the first half of the film. Shortly after this opening sequence, Martin will be depicted voyeuristically watching Sebastián in the changing rooms at the school; and when Sebastián allows Martin to spend the night in his flat, the audience is briefly presented with the image of Sebastián showering – presented via a point-of-view shot from Martin’s perspective. Throughout, the knowing and sexually confident Martin is shown to be in control of the gaze, his lustful looks – directed towards Sebastián – establishing his power and control of the situation. Whilst the general perception of films about student-teacher relationships might suggest that the pictures usually represent the teacher as a Clare Quilty-esque exploiter of youth and innocence, the reality is far more complex: films about student-teacher romances range from those that focus on infatuation and unrequited love (To Sir, With Love, James Clavell, 1967; Summer School, Carl Reiner, 1987) to those that depict the student as a femme fatale who lures a teacher to his/her doom (Election, Alexander Payne, 1999; Wild Things, John McNaughton, 1998). For at least a portion of its running time, Ausente seems to conform to the latter group of films, with Martin positioned as a ‘homme fatale’ who ensnares Sebastián and encourages him to question his own sexuality. The film differs from most films about student-teacher relationships through its focus on gay sexuality. Berger has claimed that despite its focus on the desire between student and teacher, Ausente is most definitely not about ‘abuse, because it’s not a film about abuse from an adult to a boy. It’s [about] a boy that knows about this [concept of] abuse but [is] playing with that because he is full of desire’ (FirstPost, 2011).

The structure of the sequence in which Martin voyeuristically watches Sebastián as he showers, the view through the shower screen serving to underscore Sebastián’s vulnerability (both physical and emotional), seems to allude to the infamous murder of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) in the shower in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Also like Psycho, Ausente features a major reversal about halfway through its narrative, with the (offscreen) death of Martin functioning like the pivotal murder of Marion Crane in the Hitchcock film. The structure of the sequence in which Martin voyeuristically watches Sebastián as he showers, the view through the shower screen serving to underscore Sebastián’s vulnerability (both physical and emotional), seems to allude to the infamous murder of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) in the shower in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Also like Psycho, Ausente features a major reversal about halfway through its narrative, with the (offscreen) death of Martin functioning like the pivotal murder of Marion Crane in the Hitchcock film.

The film is structured like a Hitchcockian thriller, an aspect that is underscored by the film’s brooding and ominous score (by Pedro Irusta), which at times recalls the discordant and intense scores that Ennio Morricone produced for Italian thrillers during the late-1960s and early-1970s. Irusta’s score injects even the most languid, inconsequential scene – such as a brief scene in which Sebastián wanders through his flat, searching for Martin – with an aura of menace and threat. What is being threatened is arguably not just Sebastián’s reputation and the threat of prosecution, but rather Sebastián’s confidence in his own sexuality. From early in the film, Sebastián’s cool relationship with Mariana parallels that of Martin and his female friend Ana (Rocío Pavón). Ana is introduced in a scene in which she and Martin make preparations for a visit to the cinema; discussing the film that they plan to see, their conversation is very subtly combative, predicated on misunderstandings and a failure to communicate. Likewise, Sebastián’s relationship with Mariana is undermined by a similar failure to communicate. When Sebastián tries to tell Mariana about Martin, she closes down and refuses to listen, instead forcing Sebastián to pay attention as she tells him about her own, far more trivial, worries. The disconnect in their relationship is in this scene signified through the framing and use of mise-en-scene: Sebastián and Mariana are framed separately, Sebastián relaxing on the bed and Mariana seated at a desk, in front of a computer screen.

As with Plan B, in Ausente homosexuality is presented as a taboo subject, Martin apparently concealing his sexuality from his friends – who believe that he is in a relationship with Ana. Despite the fact that Argentina was apparently the first Latin American country to legalise same-sex marriage, traditionally the macho culture of Latin America has seen homosexuality as a sign of weakness (see Corrales, 2009: np). Prejudices against homosexuality are seen throughout the film: for example, in the ‘knowing’ looks that Sebastián’s neighbours give him when they see him with Martin. Throughout the film, it is unclear which is more ‘taboo’: the idea of a relationship between a thirty-something teacher and a sixteen year old student, or the concept of same-sex desire: Sebastián’s aggressive response towards Martin’s stated desire for him seems to be predicated more on Sebastián’s insecurity in his own sexuality and his prejudice against homosexuality (which Berger is probably suggesting are both symptoms of the same ‘problem’) rather than the fact that Sebastián is Martin’s teacher. The film runs for 86:51 mins (PAL) and is uncut.

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.98:1, with anamorphic enhancement. The film seems to have been shot on digital video. Contrast levels are good, and the film is well-presented on this DVD release. The film’s aesthetic is intimate, dominated by close-ups and medium shots; much of the film is shot in low light situations.

Audio

Audio is presented through a two-channel Spanish language track with some subtle surround encoding. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

On startup, the disc opens with trailers for Plan B, Circo, Tony Manero and Post Mortem (4:18). All of these trailers are skippable. Aside from these bonus trailers, the only other extra is the theatrical trailer for Ausente (1:06). It’s an effective, brief trailer that, through its use of montage and music, foregrounds the thriller elements of the film.

Overall

Ausente is an engaging film, although it has to be said that its unusual and seemingly omnipresent score adds much to the texture of the movie, giving it the semblance of a thriller. Without its score, the film would be a very different beast entirely. All of the actors are very good and give extremely convincing performances, especially Echevarría as the conflicted Sebastián. Nevertheless, some viewers may find that, its unusual score aside, Ausente struggles to find its voice. Berger seems to anticipate these criticisms in one particular scene in which, out of the blue, Mariana tells Sebastián, ‘I’m not sure I liked the book. The story is good, but at some point it fades away. It doesn’t tell me what I would like to hear. I understand… Maybe that’s the point of all those gaps. But I felt that something was missing’. Some viewers may find that something is equally missing in Ausente: although the film is technically more mature than Berger’s debut feature Plan B, featuring more polished cinematography and editing, thematically the film treads pretty much the same ground as its predecessor – the awakening of homosexual desire in its apparently ‘straight’ protagonist. The first half of the film also seems much stronger than the second half: Martin’s plot to ensnare Sebastián is tense and well-realised, whilst following the death of Martin the narrative arguably meanders towards its conclusion. Nevertheless, Ausente is a film that is definitely worth watching, and hopefully Berger’s work will continue to develop and mature: his subtle subversion of traditional genres marks him as an interesting and unique director. Ausente has been released both alone and with Plan B, as Made in Argentina: Two Films By Marco Berger. References: BFI, 2011: ‘Absent + Q&A’. [Online.] http://www.bfi.org.uk/live/video/927 Corrales, Javier, 2009: ‘Gays in Latin America: Is the Closet Half Empty?’ Foreign Policy (18 February, 2009) [Available Online.] http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2009/02/17/gays_in_latin_america_is_the_closet_half_empty FirstPost, 2011: ‘Berlinale 2011: Argentinian director Marco Berger about his film “Absent”’. [Online.] http://www.firstpost.com/topic/event/london-film-festival-berlinale-2011-argentinean-director-marco-berger-about-his-f-video-hRAFWKhDedc-76315-15.html For more information, please visit the homepage of Network. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|