|

|

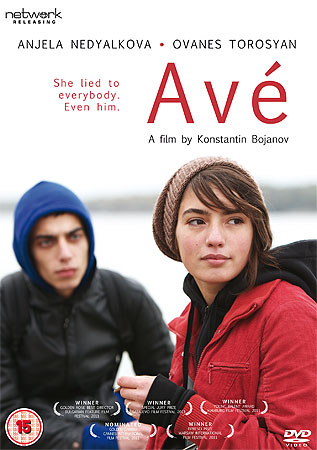

Avé

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th June 2012). |

|

The Film

Avé (Konstantin Bojanov, 2011)  Avé opens with a view panoramic view of a cityscape and, subsequently, a tracking shot that follows a young man as he enters an art studio. We soon discover that the young man is a student named Kamen (Ovanes Torosian); as the tracking shot suggests, we follow his point-of-view throughout the movie. Avé opens with a view panoramic view of a cityscape and, subsequently, a tracking shot that follows a young man as he enters an art studio. We soon discover that the young man is a student named Kamen (Ovanes Torosian); as the tracking shot suggests, we follow his point-of-view throughout the movie.

The art class is disrupted by its teacher, who takes Kamen to one side and informs him that his friend Victor has committed suicide. Kamen decides to make the journey to visit Victor’s family and attend his funeral. Along the way, he meets compulsive liar and petty thief Avélina (Angela Nedialkova). Together, Kamen and Avé hitch-hike their way across Bulgaria, Kamen revealing to Avé that the news of Victor’s death inspired guilt in him: as Kamen tells Avé, he slept with the only girl that the apparently lonely Victor loved. When they arrive at the home of Victor’s family, Kamen becomes disgusted with Avé when she pretends to be Victor’s girlfriend; she claims that she does this in order to alleviate Victor’s family’s grief, but Kamen questions her motives and her seemingly pathological need to lie. However, Kamen and Avé also find themselves drawn closer to one another.  The road movie is often seen as an almost exclusively American genre that appeared in the late-1960s and early-1970s, celebrating the wide-open spaces of North America and having its roots in the traditions of the American West, stories about the expansion of the railroads during the Nineteenth Century (for example, Frank Norris’ 1901 novel The Octopus), Depression-era stories of movement (John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, 1939) and Beat literature such as Jack Kerouac’s classic novel On the Road (1957). The road movie is often seen as an almost exclusively American genre that appeared in the late-1960s and early-1970s, celebrating the wide-open spaces of North America and having its roots in the traditions of the American West, stories about the expansion of the railroads during the Nineteenth Century (for example, Frank Norris’ 1901 novel The Octopus), Depression-era stories of movement (John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, 1939) and Beat literature such as Jack Kerouac’s classic novel On the Road (1957).

The conventions of the genre were largely defined by American movies such as Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969), Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 1970), Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop and Richard Sarafian’s Vanishing Point (1971). However, the road movie arguably has its roots in the ‘stagecoach’/‘wagon train’ subgenre of American Westerns – such as John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) or Jerry Hopper’s Pony Express (1953) – which tended to focus on groups of people, often representative of disparate social groups, who are forced to band together as they travel across dangerous Indian territory. Another subgenre of the Western, the ‘cattle drive’ or ‘cattle empire’ story, also focused on movement: the long-running television series Rawhide (1959-66) is a classic example of this subgenre. Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark declare that the ‘road has always been a persistent theme of American culture’ and its importance for American literature and cinema (and, for that matter, popular music) ‘goes back to the nation’s frontier ethos, but was transformed by the technological intersection of motion pictures and the automobile in the twentieth century’ (1997: 1). Cohan and Hark also state that in most American road movies, ‘the liberation’ represented by the road and travel is pitted ‘against the oppression of hegemonic norms’: the road represents an escape from a stagnant and stultifying life, and travelling on it may be perceived as an act of rebellion (ibid.). As S Ward claims, the road movie invariably features protagonists who move ‘from the secure bounds of society’s order into a phase of disorder which threatens social cohesion’; the anti-heroes of classic American road movies are ‘youthful [and] rebellious’ and ‘do not respect “borders, positions, rules”’ (2012: 197). For example, in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) Marion Crane’s (Janet Leigh) fateful decision to flee Phoenix, which results in her deadly stay at the Bates Motel, is precipitated by a criminal act: she steals money from her employer.  Of course, the road movie is not exclusively American, and in fact one of the most highly-regarded American road movies – Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984) – was directed by a European filmmaker. Outside the United States, filmmakers have adapted the form of the road movie for their own ends. However, very often these non-American road movies still depict the road and travel as symbolic of freedom from conventional life and are arguably indebted to the American roots of the genre; and as in American road movies, the protagonists of these films are usually painted as rebels or, occasionally, criminals who have a liminal existence. Their journeys are often precipitated by the identification of a lack or the loss of a friend/relative. For example, Chris Petit’s Radio On (1979), a rare British road movie, features a protagonist who uses England’s motorways to travel from London to Bristol to investigate the suicide of his brother. Of course, the road movie is not exclusively American, and in fact one of the most highly-regarded American road movies – Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984) – was directed by a European filmmaker. Outside the United States, filmmakers have adapted the form of the road movie for their own ends. However, very often these non-American road movies still depict the road and travel as symbolic of freedom from conventional life and are arguably indebted to the American roots of the genre; and as in American road movies, the protagonists of these films are usually painted as rebels or, occasionally, criminals who have a liminal existence. Their journeys are often precipitated by the identification of a lack or the loss of a friend/relative. For example, Chris Petit’s Radio On (1979), a rare British road movie, features a protagonist who uses England’s motorways to travel from London to Bristol to investigate the suicide of his brother.

A Bulgarian road film, Avé has overt echoes of several American films: its protagonist Kamen’s journey to his friend’s funeral is precipitated by the news of Victor’s suicide, and in many ways it recalls Vietnam veteran Jack Falen’s (Dennis Hopper) cross-country trip to bury his friend in Henry Jaglom’s Tracks (1976); and Kamen’s companion Avé’s apparently compulsive need to lie about her past and constant attempts to reinvent herself recalls the chameleon-like GTO’s (Warren Oates) persistent untruths about his past in Monte Hellman’s existentialist Two-Lane Blacktop. Like GTO, Avé’s lies about her past signify her desperation to ‘escape from [her]self, racing against [her] disappointing past for the prize of a fulfilling future’ (Gisonny, 2009: np). From the outset, Avé’s lies involve Kamen. When a car stops by the roadside to let Kamen in, Avé also steps into the car and claims to the driver that she and Kamen are travelling together. This continues, and in each vehicle Avé tells a bigger lie about her and Kamen, culminating in a tense sequence in which Kamen and Avé are picked up by a cautious middle-aged man who reveals that he only allowed the pair to travel in his car because his brother was a soldier who was killed in Iraq – and he has been led by Avé to believe that Kamen’s brother was also killed in Iraq. At this point, Kamen becomes increasingly angry with Avé, apologising to the man who has offered them a lift and informing him that Avé has lied to him. Things come to a head when Kamen confronts Avé about her lies to Victor’s family: Avé believes she is offering comfort to them by asserting that she was Victor’s girlfriend, but Kamen believes her deception is nothing but harmful. Avé comes to realise Victor’s point of view when, as they depart from Victor’s home, Victor’s mother gives her a small handful of family heirlooms to pass on to her own children. In a moment well-played by Nedialkova, Avé’s face betrays her regret but as, during her stay with Victor’s family, she has surrounded herself with lies, she has no choice but to carry on with the façade she has created.  The relationship between Avé and Kamen is almost dialectical, predicated on Avé’s belief that deception is acceptable and sometimes necessary, and Kamen’s firmly held belief that the truth should always win out. The conflict between the two is signalled visually, through the mise-en-scene: when we are introduced to Avé, we are shown a series of striking shots in which, contrasted with the drab landscape, she and Kamen are shown in contrasting primary colours: she is wearing bright read, and he is wearing a rich blue. The relationship between Avé and Kamen is almost dialectical, predicated on Avé’s belief that deception is acceptable and sometimes necessary, and Kamen’s firmly held belief that the truth should always win out. The conflict between the two is signalled visually, through the mise-en-scene: when we are introduced to Avé, we are shown a series of striking shots in which, contrasted with the drab landscape, she and Kamen are shown in contrasting primary colours: she is wearing bright read, and he is wearing a rich blue.

On the other hand, Victor’s family also seem to share their perspective on lying with Avé. After Kamen and Avé arrive at Victor’s family home, Kamen discovers that Victor’s family have lied about Victor’s death, telling their friends and neighbours that Victor was the victim of an accidental electrocution, because as they argue it is easier for people to accept this than to attempt to understand that he committed suicide. Due to her tendency to fabricate stories about her past, significant ambiguity surrounds Avé’s past. She tells Kamen that she was raised in Delhi, where her father worked as a diplomat in the embassy. However, given her penchant for lying, Kamen seems to disbelieve her. However, later in the film it is revealed that she is being honest, and her stories about needing to find her wayward brother (who is described by one of the characters the pair meet as ‘garbage [who] leaves a stench’) have an element of truth when, after tearfully telephoning her father following her meeting with Victor’s grieving family, she is told that the police are looking for her and her brother is in a coma. Later, her brother dies, precipitating the end of her relationship with Kamen. The film runs for 82:25 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in its original screen ratio of 2.35:1, with anamorphic enhancement. The presentation of the film is fine.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel track with some subtle surround encoding. It’s not ‘showy’ by any means, and suits the film well. The spoken language is Bulgarian, with one sequence featuring some English dialogue. Burnt-in English subtitles are provided.

Extras

The only special features are bonus trailers for Afterschool, Soi Cowboy, Wah Do Dem. Sadly, there is no contextual material, which is a shame because Avé cries out for an interview or two.

Overall

The road movie is an existential genre; films that conform it its conventions often explore this aspect of the genre through their depiction of characters fleeing from their pasts, leaving the conventional world behind them. Avé is no exception, with Kamen and Avé’s journey (which, as in most road movies, is both physical and emotional/intellectual) depicted as a journey away from a past from which, as Avé discovers, it seems impossible to escape. Overt visual symbolism is used to convey this flight from the past. Shortly after beginning his journey to visit Victor, Kamen puts on a broken watch – an act which, like Captain America’s (Peter Fonda) abandoning of his watch at the start of Easy Rider, seems to suggest an attempt to step outside time and to leave conventional society behind. The road movie is an existential genre; films that conform it its conventions often explore this aspect of the genre through their depiction of characters fleeing from their pasts, leaving the conventional world behind them. Avé is no exception, with Kamen and Avé’s journey (which, as in most road movies, is both physical and emotional/intellectual) depicted as a journey away from a past from which, as Avé discovers, it seems impossible to escape. Overt visual symbolism is used to convey this flight from the past. Shortly after beginning his journey to visit Victor, Kamen puts on a broken watch – an act which, like Captain America’s (Peter Fonda) abandoning of his watch at the start of Easy Rider, seems to suggest an attempt to step outside time and to leave conventional society behind.

Apparently partly autobiographical (see Bodrog, 2011: np), Avé is an interesting, low-key road movie that treads many of the recognisable themes of the genre. This release from Network is fine, but sadly lacks any contextual material. References: Bodrog, Robert, 2011: ‘Taking Bulgarian Cinema On the Road: An Interview With Director Konstantin Bojanov’. [Online.] http://www.filmfestivals.com/en/blog/robert_bodrog/taking_bulgarian_cinema_on_the_road_an_interview_with_director_konstantin_bojanov Cohan, Steven & Hark, Ina Rae, 1997: ‘Introduction’. In: Cohan, Steven & Hark, Ina Rae (eds), 1997: The Road Movie Book. London: Routledge: 1-16 Gisonny, Chris, 2009: ‘The Criterion Collection # 414: Two-Lane Blacktop’. Slant Magazine. [Online.] http://www.slantmagazine.com/house/2009/04/the-criterion-collection-414-two-lane-blacktop/ Ward, S, 2012: ‘“Danger Zones”: The British “Road Movie” and the Liminal Landscape’. In: Andrews, Hazel & Roberts, Les (eds), 2012: Liminal Landscapes: Travel, Experiences and Spaces In-Between. London: Routledge This release has been kindly sponsored by

|

|||||

|