|

|

This Happy Breed (Blu-ray)

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th June 2012). |

|

The Film

This Happy Breed (David Lean, 1944)  When Peter Flannery wrote the teleplay for the BBC’s groundbreaking nine-part drama Our Friends in the North (1996), a sprawling but intimate representation of the effects of three decades of social change on the lives of a group of four working-class friends from Newcastle, he may very well have looked to David Lean and Noel Coward’s This Happy Breed (1944) as a precedent for the elliptical structure of his drama. Like Our Friends in the North, This Happy Breed focuses on a small ensemble grouping, the Gibbons family and their neighbours the Mitchells, and uses their story to explore the twenty years of social change that took place in the interwar years, 1919-1939, taking in such events as the burgeoning Socialist mindset, which coupled with the economic downturn of the mid-1920s led to the General Strike of 1926 (and the Jarrow marches of 1936), the rise of Fascism in Germany in 1932 and the appearance of the British ‘blackshirt’ Fascist sympathisers. However, despite the similar focus and structure of their dramas Flannery and Coward have a very different worldview and offer a very different representation of working-class life and, especially, Socialism as a means of improving the conditions of working-class people. When Peter Flannery wrote the teleplay for the BBC’s groundbreaking nine-part drama Our Friends in the North (1996), a sprawling but intimate representation of the effects of three decades of social change on the lives of a group of four working-class friends from Newcastle, he may very well have looked to David Lean and Noel Coward’s This Happy Breed (1944) as a precedent for the elliptical structure of his drama. Like Our Friends in the North, This Happy Breed focuses on a small ensemble grouping, the Gibbons family and their neighbours the Mitchells, and uses their story to explore the twenty years of social change that took place in the interwar years, 1919-1939, taking in such events as the burgeoning Socialist mindset, which coupled with the economic downturn of the mid-1920s led to the General Strike of 1926 (and the Jarrow marches of 1936), the rise of Fascism in Germany in 1932 and the appearance of the British ‘blackshirt’ Fascist sympathisers. However, despite the similar focus and structure of their dramas Flannery and Coward have a very different worldview and offer a very different representation of working-class life and, especially, Socialism as a means of improving the conditions of working-class people.

Opening with the Eagle-Lion Distributors logo, This Happy Breed was adapted from Noel Coward’s play (written in 1939 but first performed in 1942) and produced by Coward himseld. The film marked the solo directorial debut of David Lean; Lean and Coward had previously co-directed In Which We Serve (1942). Coward’s play was based on his own experiences as a youth; his adopted public persona, of the upper-class dandy, obscured his lower middle-class origins. Thus, on the release of This Happy Breed Coward was criticised for his depiction of working-class life; in a review of the original play for the New York Daily, Orson Welles claimed that Coward was a ‘Mayfair playboy’ who was ‘perpetuating a British public school snobbery’ about the working-classes (Welles, quoted in Phillips, 2006: 65). However, Coward struck back, declaring ‘I can confidently assert that I know a great deal more about the hearts and minds of ordinary South Londoners than the critics give me credit for’ (Coward, quoted in ibid.). Taking its title from Shakespeare’s Richard II (which refers to the English as ‘This Happy Breed of men’), the film adaptation of This Happy Breed opens with an opening declaration, via an onscreen title, that ‘This is the story of a London family from 1919 to 1939’. An aerial shot of the back of a row of Victorian terraces in South London is accompanied by a narration (by Laurence Olivier): ‘After four long years of war, the men are coming home’. A throng of disembodied voices is heard singing the music hall song ‘Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty’. The narration continues: ‘Hundreds and hundreds of houses are becoming homes once more’. The camera moves closer to one of the houses, and with a dissolve to mark a shot transition the camera moves through the back of the house and towards the front door. (Hitchcock would use a very similar opening for his 1960 film Psycho, which begins with an aerial shot of Phoenix and uses a dissolve to take us through the window of the hotel room in which the characters of Marion and Sam are having their illicit lunchtime liaison.)  This sequence marks the beginning of the film: the Gibbons family move into the house, number 17 Sycamore Road, Clapham Common. The Gibbons family consists of Frank (Robert Lewton), his wife Ethel (Celia Johnson), Frank’s sister Sylvia (Alison Leggatt), Frank and Ethel’s children Vi (Eileen Erskine), Queenie (Kay Walsh) and Reg (John Blythe). Frank is ‘demob happy’ and has acquired a new job at a travel agent’s. He discovers that his next door neighbour is a former regimental chum, Bob Mitchell (Stanley Holloway). Bob has a son named Billy (John Mills), and before long Billy has begun courting Queenie. The film follows the family’s during the years between 1919 and 1939, sketching in historical events and relating their effect on the Gibbonses, and the inevitable sense of loss as the Frank and Ethel’s children leave home. This sequence marks the beginning of the film: the Gibbons family move into the house, number 17 Sycamore Road, Clapham Common. The Gibbons family consists of Frank (Robert Lewton), his wife Ethel (Celia Johnson), Frank’s sister Sylvia (Alison Leggatt), Frank and Ethel’s children Vi (Eileen Erskine), Queenie (Kay Walsh) and Reg (John Blythe). Frank is ‘demob happy’ and has acquired a new job at a travel agent’s. He discovers that his next door neighbour is a former regimental chum, Bob Mitchell (Stanley Holloway). Bob has a son named Billy (John Mills), and before long Billy has begun courting Queenie. The film follows the family’s during the years between 1919 and 1939, sketching in historical events and relating their effect on the Gibbonses, and the inevitable sense of loss as the Frank and Ethel’s children leave home.

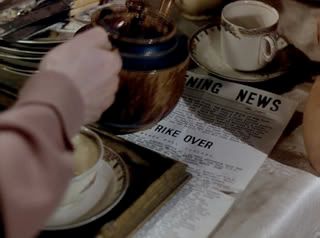

Although the film focuses on the effects that social change have on the Gibbons family unit, the social context is sketched in through montages depicting of newspaper headlines or, in the case of the sequence which touches on the 1926 General Strike, brief shots of striking workers (and, in one scene, the Gibbonses walk past a blackshirt ranting at Speaker’s Corner). The group of films that This Happy Breed belongs to draw on the conventions of the British documentary movement (ie, its focus on public life) and try to integrate this with the conventions of the domestic ‘women’s picture’ (which focuses on private life) (Higson, 1994: 68). The film thus brings together both the public and the private spheres of social life. In his 1994 analysis of This Happy Breed, Andrew Higson suggests that films of this type ‘clearly owe a great deal to the documentary idea: they seek to authenticate their fictions by drawing on the rhetoric of documentary […] and they establish a relatively expansive narrative space—the space of the nation—by employing certain of British documentary’s montage strategies’ (ibid.).  Indeed, in 1947 Dilys Powell commented that British wartime cinema confronted ‘[t]hemes which would once have been thought too serious or too controversial for the ordinary spectator’ and showed a ‘desire for solidity and truth’ (Powell, quoted in Richards & Sheridan, 1987: 14). Powell suggested that ‘we have seen how the semi-documentary film has gained a hold over British imaginations’ and suggested that ‘even in the film of simple fiction, the demand has grown for knowledge and understanding’ (Powell, quoted in ibid.). as a consequence, she concluded that ‘[t]he British no longer demand pure fantasy in their films; they can be receptive also to the imaginative interpretation of everyday life’ (Powell, quoted in ibid.). As an example of this trend, This Happy Breed is structured in the manner of a documentary, in an elliptical and non-linear way with a number of interweaving plots and an episodic structure (which frustrated some contemporary critics): as in a traditional documentary depiction of everyday life, there is no ‘central disruptive force that sets the narrative in motion’ and no ‘narrative enigma to be solved’ (Higson, 1994: 73). Indeed, in 1947 Dilys Powell commented that British wartime cinema confronted ‘[t]hemes which would once have been thought too serious or too controversial for the ordinary spectator’ and showed a ‘desire for solidity and truth’ (Powell, quoted in Richards & Sheridan, 1987: 14). Powell suggested that ‘we have seen how the semi-documentary film has gained a hold over British imaginations’ and suggested that ‘even in the film of simple fiction, the demand has grown for knowledge and understanding’ (Powell, quoted in ibid.). as a consequence, she concluded that ‘[t]he British no longer demand pure fantasy in their films; they can be receptive also to the imaginative interpretation of everyday life’ (Powell, quoted in ibid.). As an example of this trend, This Happy Breed is structured in the manner of a documentary, in an elliptical and non-linear way with a number of interweaving plots and an episodic structure (which frustrated some contemporary critics): as in a traditional documentary depiction of everyday life, there is no ‘central disruptive force that sets the narrative in motion’ and no ‘narrative enigma to be solved’ (Higson, 1994: 73).

The film begins after the central ‘disruptive force’ to the lives of most British people during the first few decades of the Twentieth Century, the First World War. The just-demobbed Frank jokily dismisses his wife’s concern for him after his experiences during the war: ‘Me perishing on a field of slaughter? What a chance!’ Trying to allay his wife’s worries, he declares ‘What’s the use of upsetting yourself? There isn’t going to be another war anyway’. However, Ethel has another perspective on the issue, telling Frank that ‘There’ll always be wars, so long as men are such fools as to want to go to them’. The film’s narrative will follow the Gibbonses up to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Produced in 1944, the film was Coward’s patriotic attempt at bolstering wartime spirits; Andrew Higson notes that This Happy Breed should ‘be understood as one small facet in the process of ideological reconstruction, an attempt to renew the nation’s self-image’ (Higson, 1994: 67). As such, the film tries to come to terms with what ‘Englishness’ means for these regular people from South London, and in doing so the picture constructs ‘an image of an organic national community, the British people as one large happy family, and nationhood as a timeless and invariant category’ (ibid.). Along with Millions Like Us (Frank Launder & Sidney Gilliat, 1943), This Happy Breed offered a cinematic representation of a ‘core national identity’ in which British society is represented as a ‘nation of community, and a relatively centred, stable and consensual community at that’ (Higson, 2000: 44). This group of films has come to be labelled by Pam Cook as ‘consensus films’, and citing Cook’s work Higson argues that these consensus films are in stark contrast with ‘much more transgressive, visions of the nation’, such as to be found in some of ‘the Gainsborough costume dramas of the period, films like Madonna of the Seven Moons (Arthur Crabtree, 1944), The Wicked Lady (Leslie Arliss, 1945) and Caravan (Arthur Crabtree, 1946)’ (Cook, cited in ibid.).  This approach to national identity is echoed in the dialogue. Discussing Reg and his friend Sam Leadbitter’s (Guy Verney) Socialist ideals with Ethel (described by Ethel as ‘that Bolshie business’), Frank says, ‘There’s something to be said for it. There’s always something to be said for everything. Where they go wrong is trying to get things done too quickly, and we don’t like things done quickly in this country. It’s like gardening. Somebody once said we was a nation of gardeners, and they weren’t far wrong. We like planting things and watching them grow, looking out for changes in the weather [….] What works in other countries won’t work in this one. We’ve got our own way of settling things. It may be a bit slow […] but it suits us all right, and it always will’. In Britain Can Take It: British Cinema in the Second World War, Aldgate and Richards (2007) note that Frank’s monologue is generally interpreted as a focused declaration of Coward’s own ‘Conservative evolutionary philosophy’ and a plea for British people to, when the Second World War ends, ‘return to “normalcy”’ (211). This approach to national identity is echoed in the dialogue. Discussing Reg and his friend Sam Leadbitter’s (Guy Verney) Socialist ideals with Ethel (described by Ethel as ‘that Bolshie business’), Frank says, ‘There’s something to be said for it. There’s always something to be said for everything. Where they go wrong is trying to get things done too quickly, and we don’t like things done quickly in this country. It’s like gardening. Somebody once said we was a nation of gardeners, and they weren’t far wrong. We like planting things and watching them grow, looking out for changes in the weather [….] What works in other countries won’t work in this one. We’ve got our own way of settling things. It may be a bit slow […] but it suits us all right, and it always will’. In Britain Can Take It: British Cinema in the Second World War, Aldgate and Richards (2007) note that Frank’s monologue is generally interpreted as a focused declaration of Coward’s own ‘Conservative evolutionary philosophy’ and a plea for British people to, when the Second World War ends, ‘return to “normalcy”’ (211).

Frank tries to educate his children about the importance of understanding their cultural history. Taking the family to The British Empire Exhibition of 1924, Frank despondently watches his children traipse around the fairground rides rather than learning about their nation’s past, grumbling to Ethel that ‘I brought ‘em ‘ere to see the glories of the empire, and all they think about is going on the dodgems’. As Frank later reminds Reg, ‘I belong to a generation of men, most of whom aren’t here anymore. We all did the same thing for the same reason, no matter what we thought about politics [….] And as a matter of fact, several things happened. One of them was, this country suddenly got tired. She’s tired now. But the old lady’s got stamina, don’t you make any mistake about that. And it’s up to us ordinary people to keep things steady. And that’s your job, and just you remember it’. This message (of ‘keep[ing] things steady’ and understanding the importance of duty ‘no matter what we thought about politics’) is indexical of Coward’s conservative worldview; in The British Working Class in Postwar Film (2003), Phillip John Gillet writes of ‘Coward’s failure to perceive social change’ (35).  The film dismisses politically-active Socialism as a means of effecting social change through the representation of Sam Leadbitter as an arrogant and somewhat pompous youth who breaks up the Christmas celebrations to make a speech, addressing Vi, Queenie and Reg as ‘comrades’ and declaring that ‘it’s really against my principles to hobnob to any great extent with the bourgeoisie’. He reminds them that ‘There are millions and millions of homes today where Christmas is naught but a mockery, where there is neither warmth nor food, nor even the bare necessities of life, where little children, old before their time, huddle around a fireless grate’. In reponse to this display of self-importance, Queenie tries to burst his bubble by joking, ‘Well, they’d be just as well-off if they stayed in the middle of the room then, wouldn’t they’. When Sam hits back by stating that ‘That sort of remark, Queenie, springs from complacency, arrogance and a full stomach’, Queenie snaps back, ‘You leave my stomach out of it’. However, Sam doesn’t get the message and continues to browbeat his friends, asserting that ‘It is people like you: apathetic, unthinking, docile supporters of a capitalistic system which is a disgrace to civilisation, who are responsible for at least three quarters of the cruel sufferance of the world. As long as you can earn your miserable little salaries and go to the pictures and enjoy yourselves, the rest of suffering humanity can go hang, can’t it. You’re too busy getting all weepy over Rudolph Valentino to spare any tears for the workers of the world’. The film dismisses politically-active Socialism as a means of effecting social change through the representation of Sam Leadbitter as an arrogant and somewhat pompous youth who breaks up the Christmas celebrations to make a speech, addressing Vi, Queenie and Reg as ‘comrades’ and declaring that ‘it’s really against my principles to hobnob to any great extent with the bourgeoisie’. He reminds them that ‘There are millions and millions of homes today where Christmas is naught but a mockery, where there is neither warmth nor food, nor even the bare necessities of life, where little children, old before their time, huddle around a fireless grate’. In reponse to this display of self-importance, Queenie tries to burst his bubble by joking, ‘Well, they’d be just as well-off if they stayed in the middle of the room then, wouldn’t they’. When Sam hits back by stating that ‘That sort of remark, Queenie, springs from complacency, arrogance and a full stomach’, Queenie snaps back, ‘You leave my stomach out of it’. However, Sam doesn’t get the message and continues to browbeat his friends, asserting that ‘It is people like you: apathetic, unthinking, docile supporters of a capitalistic system which is a disgrace to civilisation, who are responsible for at least three quarters of the cruel sufferance of the world. As long as you can earn your miserable little salaries and go to the pictures and enjoy yourselves, the rest of suffering humanity can go hang, can’t it. You’re too busy getting all weepy over Rudolph Valentino to spare any tears for the workers of the world’.

Later, when after the General Strike Reg, sporting a nasty bump on the head, returns home with Sam, Vi (Eileen Erskine) snaps at Sam, telling him that ‘You’ve been filling him [Reg] up with your wrotten ideas until he can’t see straight. There may be a lot of things wrong, but it’s not a noisy great gasbag like you going to set them right’. Not long after, Frank visits Reg in his bedroom and offers him some quiet advice about his engagement with Socialism whilst also outlining the conservative worldview that runs throughout the film: ‘You’ve got a right to your opinions, same as I’ve got a right to mine. Anyone with any sense knows about the injustice of some people having a lot and other people having nothing at all. But where you make a mistake is blaming it all on systems and governments. You’ve got to go deeper than that to find out the cause of most of the troubles in this world. Once you’ve had a good look, you’ll see—likely as not—that good old human nature’s at the bottom of the whole thing’.  Eventually, both Sam and Reg leave their political beliefs behind in order to start their own families. Reg marries Phyliss Blake (Betty Fleetwood), and Sam marries Vi. Aldgate and Richards comment that ‘[f]or all the younger Gibbonses flirt with change, they settle in the end for the tried and true. Son Reg flirts with radical politics but is tamed by marriage. Communist son-in-law Sam similarly finds domestic bliss a happy substitute for world revolution. Daughter Queenie rejects her background as “common” and runs away in search of the bright lights. But she too eventually settles for marriage to the boy next door and shows every sign of becoming the archetypal wife and mother’ (op cit.: 211). In light of this Aldgate and Richards conclude that in the film, ‘[m]arriage, home and the family are thus seen to be playing a profoundly political role by depoliticizing the lower middle class and deploying them in defence of the status quo’ (ibid.). At the time of the film’s original release in 1944, Edgar Anstey similarly suggested in his review of the film for The Spectator that ‘This Happy Breed adduces no evidence of better times to come’ (Anstey, quoted in Higson, 1994: 74). Andrew Higson suggests that the film privileges ‘the apparent stability of class difference and deference, rather than any democratic settlement’ (ibid.: 74). Eventually, both Sam and Reg leave their political beliefs behind in order to start their own families. Reg marries Phyliss Blake (Betty Fleetwood), and Sam marries Vi. Aldgate and Richards comment that ‘[f]or all the younger Gibbonses flirt with change, they settle in the end for the tried and true. Son Reg flirts with radical politics but is tamed by marriage. Communist son-in-law Sam similarly finds domestic bliss a happy substitute for world revolution. Daughter Queenie rejects her background as “common” and runs away in search of the bright lights. But she too eventually settles for marriage to the boy next door and shows every sign of becoming the archetypal wife and mother’ (op cit.: 211). In light of this Aldgate and Richards conclude that in the film, ‘[m]arriage, home and the family are thus seen to be playing a profoundly political role by depoliticizing the lower middle class and deploying them in defence of the status quo’ (ibid.). At the time of the film’s original release in 1944, Edgar Anstey similarly suggested in his review of the film for The Spectator that ‘This Happy Breed adduces no evidence of better times to come’ (Anstey, quoted in Higson, 1994: 74). Andrew Higson suggests that the film privileges ‘the apparent stability of class difference and deference, rather than any democratic settlement’ (ibid.: 74).

On the other hand, the film represents Queenie in a negative light for her aspirations of moving up in the world. When Billy proposes to her, Queenie dismisses him; needled for a reason why, she tells him ‘I hate living here. I hate living in a house that’s exactly the hundreds of other houses. I hate coming home from the tube and helping mum darn dad’s socks and listening to Aunt Syl going on about how ill she is all the time. And what’s more I know why I hate it: it’s because it’s all so common’. (She concludes her speech by saying, ‘And that’s why I don’t think I’ll be a good wife for you, however much I love you’.) Later, Frank tells his friend Billy (whilst knocking back one of the many bottles of Johnnie Walker Red Label that these two friends share throughout the film), ‘Queenie, she gives me a headache with all her airs and graces. A good hiding is what she needs’. When Queenie eventually gets her comeuppance by running away with a married man who eventually deserts her, Frank intones that ‘We ought to have known something like this would happen. We let her have her own way too much, ever since she was a child’. However, having learnt her lesson eventually Queenie returns to the fold, tempered by her experiences, and begins her own family with her childhood sweetheart Billy.  On the topic of the film’s representation of women, as Reg makes preparations to marry Phyllis Frank offers his son some advice: ‘Marriage is a bit different, you know, from just having a bit of fun. Women aren’t all the same, you know, not by any manner of means. Some of ‘em don’t care what happens so long as they have a good time. Marriage isn’t important to ‘em, beyond having a ring and being Mrs Whatever-It-Is’. Frank advises Reg that Phyllis loves him ‘very much’ and may therefore be a bit ‘sensitive’ about certain things. He then tells Reg, ‘And if, later on—a long time later on—you should get yourself caught up with someone else, just see to it that Phyllis doesn’t get ear of it. Put your wife first, always. Anything that’s likely to bust up your ‘ome, your wife and your kids, well it’s just not worth it. You remember that and you won’t go far wrong’. On the topic of the film’s representation of women, as Reg makes preparations to marry Phyllis Frank offers his son some advice: ‘Marriage is a bit different, you know, from just having a bit of fun. Women aren’t all the same, you know, not by any manner of means. Some of ‘em don’t care what happens so long as they have a good time. Marriage isn’t important to ‘em, beyond having a ring and being Mrs Whatever-It-Is’. Frank advises Reg that Phyllis loves him ‘very much’ and may therefore be a bit ‘sensitive’ about certain things. He then tells Reg, ‘And if, later on—a long time later on—you should get yourself caught up with someone else, just see to it that Phyllis doesn’t get ear of it. Put your wife first, always. Anything that’s likely to bust up your ‘ome, your wife and your kids, well it’s just not worth it. You remember that and you won’t go far wrong’.

The film is beautifully shot by Ronald Neames and, along with Blithe Spirit (1945), was one of only three David Lean films shot on three-strip Technicolor film. As noted above This Happy Breed also makes excellent use of the conventions of the documentary tradition, whose aesthetic was gradually working its way into narrative features via such devices as the use of montage in order to signify the passage of time. Regardless of its conservative approach to social change and its demand to ‘keep things steady’, the film offers a warm and moving portrait of a family as it passes through key stages in the history of the nation; the film is a portrait of a stable national identity and a document of social change and development during a specific period of British history. It is no mistake that This Happy Breed is considered one of the iconic British films of the war years, and Frank’s summing-up probably has more resonance for audiences now than it did in 1944; sharing yet another bottle of Johnnie Walker Red Label with his friend and neighbour Bob Mitchell, Frank ponders: ‘I wonder what happens to rooms when people give them up, go away and leave the house empty [….] I wonder what the next people who live in this room will be like, whether they’ll feel any bits of us about the place’. Would Frank and his generation recognise ‘any bits of us about the place’ in modern Britain?

Video

As with Network’s DVD release from 2009, this new Blu-ray release contains the BFI National Archive’s restoration of This Happy Breed, financed by The David Lean Foundation. The restoration comparison featurette included on the Blu-ray depicts a split-screen comparison of the unrestored and restored versions of the film. The restored version of This Happy Breed has a much warmer colour palette, and instances of print damage have been removed, resulting in a far more pleasing image as compared with the earlier DVD release from Carlton. (The film was shot in vibrant three-strip Technicolor in order to ‘liven up’ its otherwise sombre subject matter.) Full details of the restoration can be found on the BFI’s website. Encoded with the AVC MPEG-4 codec, this Blu-ray represents a significant Hi-Def improvement over Network’s 2009 DVD. The DVD already contained a very good presentation of the film, but - playing to the new format’s strengths - this Blu-ray release trumps it in terms of detail and clarity, and the film has a pleasingly film-like appearance with a natural grain structure. It’s easily the best presentation of this film that I’ve seen. The film runs for 110:37 mins and is presented in its original Academy ratio of 1.33:1. Please note that as I don’t have the hardware to take screengrabs from Blu-ray discs, the images used in this review have been taken from Network’s 2009 DVD release of the same restoration of This Happy Breed and are therefore for illustration purposes only. They are in no way intended to be representative of the quality of this Blu-ray release.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel linear PCM mono track. This too has been subject to some heavy restoration. It is clear throughout. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

Spread over two discs, this release contains an array of contextual material. Disc one (Blu-ray) includes: - the film’s original trailer (2:39). - the re-release trailer (2:24). - a restoration comparison featurette (7:24) which provides a split-screen comparison of the unrestored and restored versions of the film. Aside from the removal of print damage, what’s immediately noticeable is that the restored version of the film clearly has a warmer, more naturalistic colour palette. Four galleries are included: a ‘behind the scenes’ gallery of images from the shooting of the picture (1:11); a portraits gallery depicting the cast (0:47); a production gallery with stills from the production of the film (3:23); a publicity gallery containing the film’s pressbook (0:35). According to the promotional material, this seems to be a two-disc set. Only the first disc was provided for this review, but the second disc (a DVD) would appear to be the second disc from Network’s 2009 DVD release, which contained two episodes of The South Bank Show: - ‘David Lean – A Life in Film’ (131:50). A title card at the front-end of this show states that some edits have been made ‘[f]or contractual reasons’. These edits have been made to The South Bank Show’s iconic titles sequence and its use of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s ‘Variations’. Produced in 1985 by London Weekend Television and broadcast on the 17th of February of that year, this episode offers an intimate portrait of Lean. Illustrated with ample clips from Lean’s films, this episode of ITV’s flagship arts programme follows the production of Lean’s 1985 adaptation of E. M. Forster’s novel A Passage to India, interviewing Lean on set and offering insight into the great director’s working methods. - ‘David Lean and Robert Bolt’ (41:24). This episode of The South Bank Show was produced in 1990 and features David Lean conversing with his frequent collaborator, the screenwriter Robert Bolt. The collaborations between Bolt and Lean arguably represent the best group of films within Lean’s canon. Lean and Bolt discuss their work together and separately (in interview with Melvyn Bragg), including their unfinished adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novel Nostromo. The episode offers a great deal of insight into the key films on which Bolt and Lean collaborated, including Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago and Ryan’s Daughter. (Most astutely, Bolt suggests that all of the films on which he collaborated with Lean ‘are about a man who [….] forces himself against the times’.)

Overall

A key film in the development of David Lean’s career, This Happy Breed is also a key film within British cinema of the 1940s, although it’s often placed in comparison with the more transgressive and more progressive Gainsborough costume dramas of the period. The film’s worldview is certainly more than a little conservative, and this can be taken as evidence of Coward’s authorial input into the film. This Happy Breed is beautifully shot by Roland Neames too, and the performances are very strong. On the whole, the film is a moving experience; typically for a 1940s picture, it utilises the conventions of the documentary movement in order to offer a portrait of British life during a specific period in the nation’s history, and uses the story of the Gibbons family in order to define national identity for a society that, at that time, was still in the throes of the Second World War. It’s perhaps not the best of the collaborations between Noel Coward and David Lean (1945’s Brief Encounter or In Which We Serve perhaps have more immediate resonance for modern viewers), and this period of Lean’s career is arguably trumped by his postwar films, such as Great Expectations (1946) and the films on which he collaborated with screenwriter Robert Bolt. However, This Happy Breed is still a very significant part of British cinema history, especially for its focus on the ways in which British national identity has been constructed over time. Network’s new Blu-ray release of this film is very impressive. The presentation of the film is excellent and represents a strong improvement over Network’s 2009 DVD, which was based on the same restoration used here. This release clearly plays to the format’s strengths, and the transfer is natural and film-like. It’s also supported by a vast range of contextual material, and the inclusion of the two South Bank Show episodes about Lean’s work is to be applauded. The restoration of the main feature easily surpasses previous home video releases of This Happy Breed, and for fans of British cinema in general, or of Lean’s work in particular, this Blu-ray release of this classic film comes with the highest recommendation. References: Aldgate, Tony & Richards, Jeffrey, 2007: Britain Can Take It: British Cinema in the Second World War. London I. B. Tauris (Revised Edition) Gillet, Phillip John, 2003: The British Working Class in Postwar Film. Manchester University Press Higson, Andrew, 1994: ‘Re-Constructing the Nation: This Happy Breed, 1944’. In: Dixon, Wheeler Winston (ed), 1994: Re-Viewing British Cinema, 1900-1992: Essays and Interviews. State University of New York Press Higson, Andrew, 2000: ‘The Instability of the National’. In: Ashby, Justine & Higson, Andrew (eds), 2000: British Cinema, Past and Present. London: Routledge: 35-50 Landy, Marcia, 2000: ‘The Other Side of Paradise: British Cinema from an American Perspective’. In: Ashby, Justine & Higson, Andrew (eds), 2000: British Cinema, Past and Present. London: Routledge: 63-79 Lean, Sandra & Chattington, Barry, 2001: David Lean: An Intimate Portrait. New York: Universe Publishing Phillips, Gene D. 2006: Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. University Press of Kentucky Richards, Jeffrey & Sheridan, Dorothy, 1987: Mass Observation at the Movies. London: Routledge For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|