|

|

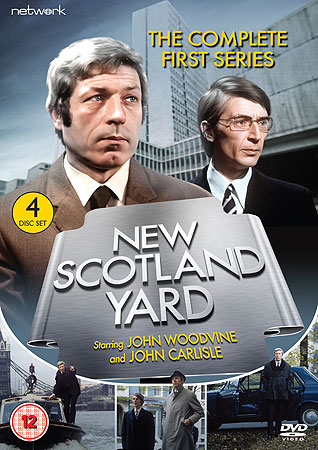

New Scotland Yard: The Complete First Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th July 2012). |

|

The Show

New Scotland Yard: The Complete First Series (LWT, 1972)  Described on the BFI’s ScreenOnline web resource as ‘barely remembered’, New Scotland Yard (LWT, 1972-4) was part of a group of early-1970s crime dramas that interrogated ideas about ‘traditional’ police methods (Delaney, 2003: np). Sean Delaney claims that ‘the first of this wave’ was Euston Film’s action-oriented revamp of Special Branch (Thames 1973-4), and this era of police drama would find its most popular expression in The Sweeney (Thames, 1974-8) (ibid.). To some extent, these series drew on the depiction of anti-establishment policemen in American films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) and Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971). A direct forerunner of The Sweeney, New Scotland Yard was originally broadcast alongside the newer, more action-oriented incarnation of Special Branch: where the first series of the reinvented Special Branch was scheduled on a Wednesday evening (with the second series being moved to a Thursday), New Scotland Yard was broadcast on a Saturday. As with Special Branch, the opening titles sequence of New Scotland Yard establishes it as a fast-paced, hard-hitting series: via rapid montage and what are almost ‘smash cuts’, we are shown the iconic scenery of London as police vehicles travel along its roads. All of this is accompanied by exciting, slightly aggressive music. Described on the BFI’s ScreenOnline web resource as ‘barely remembered’, New Scotland Yard (LWT, 1972-4) was part of a group of early-1970s crime dramas that interrogated ideas about ‘traditional’ police methods (Delaney, 2003: np). Sean Delaney claims that ‘the first of this wave’ was Euston Film’s action-oriented revamp of Special Branch (Thames 1973-4), and this era of police drama would find its most popular expression in The Sweeney (Thames, 1974-8) (ibid.). To some extent, these series drew on the depiction of anti-establishment policemen in American films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) and Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971). A direct forerunner of The Sweeney, New Scotland Yard was originally broadcast alongside the newer, more action-oriented incarnation of Special Branch: where the first series of the reinvented Special Branch was scheduled on a Wednesday evening (with the second series being moved to a Thursday), New Scotland Yard was broadcast on a Saturday. As with Special Branch, the opening titles sequence of New Scotland Yard establishes it as a fast-paced, hard-hitting series: via rapid montage and what are almost ‘smash cuts’, we are shown the iconic scenery of London as police vehicles travel along its roads. All of this is accompanied by exciting, slightly aggressive music.

Traditionally, in British television drama police work was shown as a form of pastoral care, with the uniformed community policeman depicted as a friendly, paternal figure – as in Dixon of Dock Green (BBC, 1955-76). However, during the late 1960s and 1970s programmes increasingly began to focus on non-uniformed police who were willing to bend the rules as a means of negotiating the fine line between law and disorder. An influential 1994 essay on the representation of policing on British television (‘The dialectics of Dixon: the changing image of the TV cop’) established a dialectical relationship between Dixon of Dock Green and The Sweeney, claiming that the conflict between friendly, paternal uniformed police and rule-breaking ‘coppers in disguise’ was embodied in the 1980s series The Bill (Thames/ITV Studios, 1984-2010). For Reiner, the author of ‘The dialectics of Dixon’, The Bill ‘established a state of equilibrium’ through its dramatisation of the tensions between uniformed police officers and the more non-conformist members of the CID; in this way, the series ‘achieved a balance between [the representation of policing as] care and control, and between bobby and detective’ (Reiner, cited in Leishman & Mason, 2001: 101).  New Scotland Yard was in some ways a continuation of the earlier series Scotland Yard (ABC, 1957-9), with John Woodvine reprising his role as Inspector Kingdom. Here, in New Scotland Yard, Kingdom has been promoted to the rank of Detective Chief Superintendent. He is aided in his investigations by Detective Sergeant Ward (John Carlisle). In a number of episodes, Kingdom and Ward are given information by a journalist, Harry Carson (Barry Warren). As the series progresses, Kingdom and Ward’s relationship becomes more strained, and in the later episodes the character of Ward becomes increasingly nebulous. An episodes towards the end of this first series, ‘The Banker’ opens with a nicely-staged sequence in which Ward hunts a bank robber in a trainyard. Ward catches up with the thief and, for his troubles, receives a kick in the face. He wrestles the man to the ground, but later discovers from Kingdom that the suspect has claimed ‘police brutality again, more unnecessary violence’. By this point, Ward has developed into a Jack Regan-style copper who is wiling to bend the rules, and he complains to Kingdom that ‘You can’t win, can you. Three months with the press screaming at you for results. And when you get results, they start screaming at you again’. By the final episode, Ward and Kingdom’s relationship has become almost dialectical, and in ‘And When You’re Wrong’ the audience is presented with the possibility that Ward may have (at least indirectly) been responsible for the death of a petty criminal. New Scotland Yard was in some ways a continuation of the earlier series Scotland Yard (ABC, 1957-9), with John Woodvine reprising his role as Inspector Kingdom. Here, in New Scotland Yard, Kingdom has been promoted to the rank of Detective Chief Superintendent. He is aided in his investigations by Detective Sergeant Ward (John Carlisle). In a number of episodes, Kingdom and Ward are given information by a journalist, Harry Carson (Barry Warren). As the series progresses, Kingdom and Ward’s relationship becomes more strained, and in the later episodes the character of Ward becomes increasingly nebulous. An episodes towards the end of this first series, ‘The Banker’ opens with a nicely-staged sequence in which Ward hunts a bank robber in a trainyard. Ward catches up with the thief and, for his troubles, receives a kick in the face. He wrestles the man to the ground, but later discovers from Kingdom that the suspect has claimed ‘police brutality again, more unnecessary violence’. By this point, Ward has developed into a Jack Regan-style copper who is wiling to bend the rules, and he complains to Kingdom that ‘You can’t win, can you. Three months with the press screaming at you for results. And when you get results, they start screaming at you again’. By the final episode, Ward and Kingdom’s relationship has become almost dialectical, and in ‘And When You’re Wrong’ the audience is presented with the possibility that Ward may have (at least indirectly) been responsible for the death of a petty criminal.

The episodes in this series are largely issue-led. For example, in ‘The Wrong-Un’, Kingdom and Ward investigate the murder of a prisoner. ‘We lock them up in medieval buildings, we give them futile work to do, they can’t even make the simplest decisions about their own lives. Is it surprising they’re antisocial?’ Kingdom reflects: ‘Now for the first time in their life they’ve got a chance to play us up without reprisals’. Meanwhile, ‘Shock Tactics’ focuses on the murder of a middle-aged woman by her husband. Kingdom and Ward restage the murder, which terrifies the suspect into confessing. However, in court they have to defend the confession they extracted, which is claimed to be ‘fruit from the poisonous tree’. We are encouraged to question whether the methods that Kingdom and Ward used to catch the killer are justified.  The issue-led focus of the series is established in its opening episode, in which a demonstration by socialist students in support of an imprisoned West German student leader is disrupted by a right wing organisation called the Law & Order Brigade. During the fracas, one of the students, Swanson, is killed; and the organiser of the student demonstration - a rabble-rousing, middle-aged man named George Bowen – claims that a policeman is guilty of Swanson’s murder. The accused policeman The issue-led focus of the series is established in its opening episode, in which a demonstration by socialist students in support of an imprisoned West German student leader is disrupted by a right wing organisation called the Law & Order Brigade. During the fracas, one of the students, Swanson, is killed; and the organiser of the student demonstration - a rabble-rousing, middle-aged man named George Bowen – claims that a policeman is guilty of Swanson’s murder. The accused policeman

The brutality of the demonstration is depicted succinctly: we are shown newsreel-style footage of the event, and we are also told that the protestors rolled marbles under the hooves of the police horses and threw darts at their flanks. The guilt or innocence of the accused policeman is difficult to determine, and both the left-wing student leaders and the right-wing Law & Order Brigade are criticised. It’s a fascinating episode that asks hard questions and provides equally difficult answers, showing that the series isn’t willing to mollycoddle its audience or romanticise either crime or the policework that follows it. That said, a couple of episodes skirt the edges of sensationalism. ‘The Come Back’ focuses on an ex-convict who believes he has been wronged. He tracks down the witnesses in his trial and executes them. In the opening sequence of this episode, the ex-convict wakes a banker in his bed by whispering, ‘Allo, Mr Dobson. You remember me?’ He then observes, ‘Nice place you got ‘ere, though. At least your widow will be able to mourn you in comfort [….] Enjoy your retirement, Mr Dobson’, before shooting his victim. It’s a sequence that wouldn’t be out of place in a 1960s Edgar Wallace adaptation or a thrilling all’italiana such as Dario Argento’s The Bird With the Crystal Plumage (1969), whilst the theme of a criminal returning from a spell in prison and wreaking vengeance on those who put him there is reminiscent of Sitting Target (Douglas Hickox, 1972), released in the same year as the broadcast of this series. DISC ONE: ‘Point of Impact’ (48:07) ‘The Come Back’ (49:23) ‘Memory of a Gauntlet’ (52:02) Gallery (5:13) DISC TWO: ‘The Palais Romeo’ (50:40) ‘Hard Contract’ (51:41) ‘Shock Tactics’ (52:11) DISC THREE: ‘The Wrong-Un’ (51:31) ‘Fire in a Honey Pot’ (51:04) ‘Perfect in Every Way’ (51:35) DISC FOUR: ‘The Banker’ (50:15) ‘Ask No Questions’ (51:31) ‘Reunion’ (51:30) ‘And When You’re Wrong’ (51:51)

Video

The episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 1.33:1. The series is largely studio-bound and recorded on videotape, with some location work shot on 16mm film. As suggested above, some episodes (such as ‘The Banker’, with its opening manhunt in a trainyard) feature some strong location work. The episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 1.33:1. The series is largely studio-bound and recorded on videotape, with some location work shot on 16mm film. As suggested above, some episodes (such as ‘The Banker’, with its opening manhunt in a trainyard) feature some strong location work.

The original break bumpers are intact, and the episodes seem to be intact. The episodes look about as good as one would expect for a (mostly) tape-shot series of this vintage. The in-studio footage displays the kind of blown highlights that are a characteristic of taped series. On the whole, the episodes are quite well-preserved, although some of them suffer from some intermittent tape damage (‘Ask No Questions’ suffers the worst).

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel monaural track. This is clear and without issues. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Disc one contains a stills gallery.

Overall

An entertaining series from a pivotal era in the development of the genre, New Scotland Yard bridges the 1960s police procedurals and the later era of shows like The Sweeney and The Professionals (LWT, 1977-83). Contemporaneous to Special Branch, New Scotland Yard is less focused on action. There is a cynicism here which is also present in Special Branch and The Sweeney: at the end of ‘The Wrong-Un’, Kingdom and a colleague note that, ‘It doesn’t help, this sort of incident [….] Anyway, the public couldn’t care less if they [the prisoners] kill each other all off. It’s the way the Home Office will use it, to keep the clocks back’. ‘The system goes on, and stays the same. All a bit pointless, isn’t it’, Kingdom adds. This cynicism runs throughout the series: the final episode ends with Kingdom asserting that, ‘In this job, when you’re right, you’re wrong; and when you’re wrong, you’re finished’. An entertaining series from a pivotal era in the development of the genre, New Scotland Yard bridges the 1960s police procedurals and the later era of shows like The Sweeney and The Professionals (LWT, 1977-83). Contemporaneous to Special Branch, New Scotland Yard is less focused on action. There is a cynicism here which is also present in Special Branch and The Sweeney: at the end of ‘The Wrong-Un’, Kingdom and a colleague note that, ‘It doesn’t help, this sort of incident [….] Anyway, the public couldn’t care less if they [the prisoners] kill each other all off. It’s the way the Home Office will use it, to keep the clocks back’. ‘The system goes on, and stays the same. All a bit pointless, isn’t it’, Kingdom adds. This cynicism runs throughout the series: the final episode ends with Kingdom asserting that, ‘In this job, when you’re right, you’re wrong; and when you’re wrong, you’re finished’.

New Scotland Yard is a fascinating issue-led series that is consistently good. This DVD release will be a welcome addition to the library of any fan of 1970s crime dramas. References: Delaney, Sean, 2003: ‘TV Police Drama’. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/445716/index.html Leishman, Frank & Mason, Paul, 2001: Policing and the Media: Facts, Fictions and Factions. London: Willan Publishing For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|