|

|

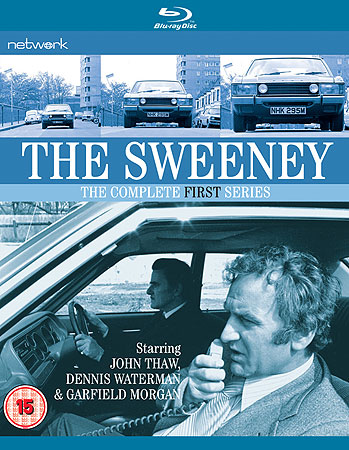

Sweeney (The): The Complete First Series (Blu-ray)

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th September 2012). |

|

The Show

The Sweeney: The Complete First Series (Thames, 1974)  Originally broadcast in 1974, this first series of The Sweeney (Thames, 1974-8) was fairly groundbreaking for its time. Memorably, The Sweeney helped to reinvent the representation of policing on television, and it was also significant in that it was one of the first wave of drama series to be shot entirely on film (16mm) rather than the traditional format of videotaped studio footage and filmed location work. Originally broadcast in 1974, this first series of The Sweeney (Thames, 1974-8) was fairly groundbreaking for its time. Memorably, The Sweeney helped to reinvent the representation of policing on television, and it was also significant in that it was one of the first wave of drama series to be shot entirely on film (16mm) rather than the traditional format of videotaped studio footage and filmed location work.

The Sweeney grew out of a one-off play, ‘Regan’, that had appeared in ITV’s single-play strand Armchair Cinema (Thames, 1974-5). ‘Regan’ introduced the two central protagonists of The Sweeney, the Flying Squad’s Detective Inspector Jack Regan (John Thaw) and Detective Sergeant George Carter (Dennis Waterman). Armchair Cinema, and ‘Regan’, had been produced by Thames Television’s subsidiary company Euston Films. Thames Television had created Euston Films in 1971, with the aim of producing quality filmed drama that was saleable to overseas broadcasters (see Fairclough & Kenwood, 2002: 39). Euston Films’ productions were to be shot wholly on film and, where possible, on location; this ethos eschewed the dominant approach in British television at the time, which was to shoot the majority of television dramas on videotape in a studio environment, with a small amount of location footage that – due to the heft of contemporary video cameras – would be shot on 16mm film. This often resulted in an aesthetic mismatch in dramas of the 1960s and 1970s, between the gritty, grainy and film-like location work and the glossy, videotaped studio footage, with the latter exhibiting the visual characteristics of video (burnt highlights, weak contrast). Euston Films’ remit therefore was to create television drama that made as much use of real locations as possible: Lez Cooke (2008) has asserted that in creating Euston Films, Thames aimed to create ‘a significant shift in policy, away from the production of studio-based plays towards location-based, filmed drama’ (123). The use of real locations helped to cut production costs: according to Fairclough and Kenwood in Sweeney! The Official Companion (2002), Euston’s approach ‘saved money by obviating the need for a studio, and added a new atmosphere of authenticity and realism courtesy of the 16mm medium’ (13). Euston also gave their directors as much creative freedom as possible, giving them the power of final cut over their work (ibid.: 43). (Traditionally, the power of final cut was held by the supervising editor and production manager.) Reflecting on the trust that Euston Films invested in its creative personnel, Lloyd Shirley commented that ‘It seemed to me that you just don’t get the best you can for the viewer by engaging a talented director, then putting such strictures around the way they work’ (Lloyd Shirley, quoted in ibid.). One of Euston Films’ first projects was a rebranded version of Thames Television’s drama series Special Branch (Thames, 1969-70; Euston Films, 1973-4). Sean Delaney (2003) has claimed that ‘the first of [the] wave’ of television dramas that interrogated ideas about traditional police methods was Euston Film’s action-oriented revamp of Special Branch (Thames 1973-4), and this era of police drama would find its most popular expression in The Sweeney (np). Thames’ first two series of Special Branch had been shot on monochrome videotape in a studio-bound environment, but Euston Films’ reworking of the series was shot completely on colour 16mm film and featured a greater emphasis on both action and location shooting. This revised version of Special Branch also featured a new cast: where the first two series of Special Branch starred Derren Nesbitt, Fulton MacKay and Wensley Pithey, Euston Films’ rebranded show featured George Sewell, Patrick Mower and Roger Rowland. The Euston Films era of Special Branch was an attempt at making a gritty, anti-establishment cop series in the mould of popular American films like Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971) and The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971): in the words of Troy Kennedy Martin, one of Euston Films’ regular writers and the creator of Z Cars (BBC, 1962-78), the new Special Branch has been described as a show that ‘featured Patrick Mower, gun in hand, finding missing pearls in the more exotic parts of Kensington’ (Fairclough & Kenwood, op cit.: 36-7). Ian Kennedy Martin originally proposed the idea that became ‘Regan’ (and, later, The Sweeney) as a replacement series for Special Branch; his original title for what became The Sweeney was The Outcasts, although according to producer Ted Childs the show was also at one point titled McClean (Fairclough & Kenwood, op cit.: 57, 58). Kennedy Martin created the character of Detective Inspector Jack Regan based on a real ‘uncorrupted cop’ that he met whilst researching at Scotland Yard (ibid.). However, it is also clear that Regan is based on the types of anti-establishment policemen that had been popularised in American films of the early 1970s, including Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971) and The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971). In ‘Regan’, for example, Kennedy Martin went to great lengths to depict a policeman who disagrees with the changes that were at that time being instigated within the police force, as per Harry Callahan’s disregard for the villain Scorpio’s Miranda rights in Dirty Harry. The Sweeney closely followed the agenda set by the rebranded Special Branch, offering a depiction of rogue policemen who were more than willing to bend the rules in order to catch the villains they are chasing. Like Special Branch, The Sweeney also offered a street-level view of crime, featuring scripts loaded with local dialect delivered so thick and fast that it arguably had the potential to alienate the overseas audiences and broadcasters that Thames apparently eagerly wished to court. Also like Special Branch, The Sweeney sometimes featured episodes in which the ‘villains’ escaped, and those episodes which contained a more conventional resolution (ie, one in which Regan and Carter arrested the criminals they hunted) were often offset by a bittersweet coda. Historically, at least in terms of its representation on British television, the subgenre of the police procedural has experienced tension between depictions of police work as a form of pastoral care, and representations of the police as little more than unorthodox punishers or controllers of crime. The former trend is exemplified by the BBC’s long-running series Dixon of Dock Green (1955-76) – with Jack Warner’s PC George Dixon as the iconic friendly, paternal community policeman – whilst the latter trend is often cited as being embodied in The Sweeney. However, this dualistic account of the development of the procedural sometimes neglects the fact that whilst Dixon of Dock Green was on air, other shows presented a more challenging depiction of police work: for example, a lineage could be drawn from Detective Inspector Barlow (Stratford Johns) in Z Cars to Jack Regan (see Rolinson, 2011: np). Nevertheless, Reiner’s distinction between the depiction of police work as pastoral care (in 1950s popular culture) and the post-The Sweeney focus on highly-specialised units and unorthodox coppers who are willing to bend the rules to get their man, offers a useful gauge of public perceptions of the roles of the police force. Both ‘Regan’ and The Sweeney were produced with former Flying Squad Sergeant Jack Quarrie as their official advisor, and an unnamed friend of Kennedy Martin’s – a then-current member of the Flying Squad – as an unofficial source of information (Fairclough & Kenwood, op cit.: 63). Dennis Waterman once commented that the advice from Quarrie sometimes conflicted with the information Kennedy Martin received from his friend in the police force: ‘The official one would say, “If you want a gun you sign three pieces of paper and go and see the armourer”, and the unofficial one would say, “Fuck off, you’ve got a gun in your safe in the office, and if you need it you use it”’ (Waterman, quoted in ibid.: 64). In the years since its original broadcast, The Sweeney has been reappropriated by ‘lad’ culture (a project still underway, as Nick Love’s recent big screen adaptation of the series might suggest), parodied for its aggressively ‘blokey’ worldview and the sometimes kitsch 1970s fashions on display, and interrogated in an ironic context by the BBC’s postmodern police drama Life on Mars (2005-6). However, as the authors of Sweeney! The Official Companion - Robert Fairclough and Mike Kenwood - have argued, the popular perception of the series as a slightly camp celebration of laddish behaviour is more than a little off the mark. Fairclough and Kenwood have asserted that ‘[a] revel in The Sweeney’s kitsch seventies iconography of kipper ties, flares and Ford Granadas doesn’t completely explain its appeal. Watching any episode today also soon gives the lie to caricatured view of the series as a simplistic “blokes and birds” shoot-‘em-up […] Regan and Carter’s witty, world-weary cynicism is a window on a Britain full of fuel shortages, IRA bombing campaigns and industrial unrest: in this dour culture, Jack and George were appealing because they were fallible. Minor villains were sent down while major ones got clean away, and the consistently well-written scripts often conveyed real rage at social inequality and injustice’ (8). A key element of the series is its focus on the internal politics of policing. Throughout the series, Regan and Carter struggle against the forces of bureaucracy that constrain them and prevent them from doing their jobs to the best of their ability. Initially, Regan is in conflict with his immediate superior, Detective Chief Inspector Frank Haskins (Garfield Morgan). Apparently based on an ‘uncorrupted cop’ who was an acquaintance of writer Ian Kennedy Martin, Regan was written to be ‘resistant to the changes in the way people were being managed within Scotland Yard and continually resorting to sharp practice’ (Fairclough & Kenwood, 2002: 57). By contrast, in ‘Regan’ and some of the early episodes of The Sweeney, Haskins is presented as ‘overly concerned with interdepartmental politics, trying to get Regan suspended as he’s convinced he’s “out of control”’ (ibid.). However, as the first series progresses, Haskins and Regan become more tolerant of each other, and throughout through the series other antagonists within the police force are introduced. In ‘Night Out’, for example, Regan is approached for help by Superintendent Grant (T P McKenna), a publicity-hungry officer in the Robbery Squad who, as Regan puts it, has ‘a certain amount of wastage amongst his personnel [….] I mean, his men keep dying on him’. Later, Regan goes on to describe Grant as ‘not a very pleasant man to know. He doesn’t like women [….] I’d put him in the same class as, er, Jack the Ripper’.  Regan’s relationship with Carter also develops throughout this first series. In ‘Regan’, Regan and Carter were at odds due to Carter’s disapproval of Regan’s methods; when Regan first approaches Carter for help with his case (‘You know more about South London than any skipper in the force, George. I need you’), Carter almost refuses, telling Regan, ‘Quite frankly, I don’t like your methods much’. However, in this first series of The Sweeney Carter defends Regan on numerous occasions. In ‘Jigsaw’, for example, Carter’s wife Alison (Stephanie Turner), a teacher, expresses her concern that Carter is throwing his career away and may end up like Regan. Carter and Alison engage in a dialogue about Regan, with Alison telling Carter that ‘If you don’t see through him [Regan] [….] you’re going to end up just like him. Jack Regan’s an unhappy, mixed-up man. I think he’s a headcase. At times, he behaves just like a monster’. ‘But he’s a good copper’, Carter protests. ‘Is that the only way to become a good copper: be tough, become an anachronistic joke just like Regan? You could have been making a good career for yourself in the force; but no, you had to team up with old Jack, back in the Sweeney’, Alison protests: [….] ‘He’s an animal, a predator’. ‘Okay, he’s an animal in a jungle, but it’s one where he knows his way around’, Carter reminds her: ‘Sure, he’ll trap his victims and he’ll give them hell, but somebody’s got to do it so you and all those kids you care about can walk the streets in safety. Now, how do you think he survives at the Yard, eh? Because he’s a professional, and there aren’t many of those about. Let me tell you that, love’. Regan’s relationship with Carter also develops throughout this first series. In ‘Regan’, Regan and Carter were at odds due to Carter’s disapproval of Regan’s methods; when Regan first approaches Carter for help with his case (‘You know more about South London than any skipper in the force, George. I need you’), Carter almost refuses, telling Regan, ‘Quite frankly, I don’t like your methods much’. However, in this first series of The Sweeney Carter defends Regan on numerous occasions. In ‘Jigsaw’, for example, Carter’s wife Alison (Stephanie Turner), a teacher, expresses her concern that Carter is throwing his career away and may end up like Regan. Carter and Alison engage in a dialogue about Regan, with Alison telling Carter that ‘If you don’t see through him [Regan] [….] you’re going to end up just like him. Jack Regan’s an unhappy, mixed-up man. I think he’s a headcase. At times, he behaves just like a monster’. ‘But he’s a good copper’, Carter protests. ‘Is that the only way to become a good copper: be tough, become an anachronistic joke just like Regan? You could have been making a good career for yourself in the force; but no, you had to team up with old Jack, back in the Sweeney’, Alison protests: [….] ‘He’s an animal, a predator’. ‘Okay, he’s an animal in a jungle, but it’s one where he knows his way around’, Carter reminds her: ‘Sure, he’ll trap his victims and he’ll give them hell, but somebody’s got to do it so you and all those kids you care about can walk the streets in safety. Now, how do you think he survives at the Yard, eh? Because he’s a professional, and there aren’t many of those about. Let me tell you that, love’.

Although Ian Kennedy Martin’s ‘Regan’ established many of the conventions of The Sweeney, the Trevor Preston-scripted ‘Ringer’ marks the series as subtly different from its predecessor. As Fairclough and Kenwood assert, the aggressive pre-titles sequence depicting a violent clash between thieves and the Flying Squad is ‘urgently directed’ and offers ‘a change of emphasis from the understated, downbeat feel of ‘Regan’ [….] [T]he uncompromising stance is reinforced by the series’ name and episode title – the first use on British television of underworld slang as the title of a drama’ (op cit.: 75). DISC ONE: ‘Ringer’ (50:38) ‘Jackpot’ (50:11) ‘Thin Ice’ (50:45) ‘Queen’s Pawn’ (50:09) Special Features: Audio commentary for ‘Ringer’ with Dennis Waterman, Garfield Morgan, writer Trevor Preston and editor Chris Burt Audio commentary for ‘Thin Ice’ with producer Ted Childs, writer Troy Kennedy-Martin and director Tom Clegg Music only tracks Interview with Ian Kennedy-Martin (12:10) ‘Queen’s Pawn’ introduction by Tony Selby (3:40) Reconstructed titles with original stills (0:44) DISC TWO: ‘Jigsaw’ (51:04) ‘Night Out’ (49:14) ‘The Placer’ (50:40) ‘Cover Story’ (50:47) Commentary for ‘Night Out’ with Director David Wickes and Assistant Director Bill Westley Commentary for ‘Night Out’ with Producer Ted Childs and Writer Troy Kennedy-Martin ‘The Placer’ introduction by John Forgeham (3:01) ‘Cover Story’ introduction by Prunella Gee (4:00) DISC THREE: ‘Golden Boy’ (50:41) ‘Stoppo Driver’ (50:44) ‘Big Spender’ (49:33) ‘Contact Breaker’ (49:44) ‘Abduction’ (51:08) Commentary for ‘Abduction’ with Dennis Waterman, Garfield Morgan, Writer Trevor Preston and Director Tom Clegg ‘Golden Boy’ introduction by Dudley Sutton (3:20) ‘Stoppo Driver’ introduction by Billy Murray (3:45) ‘Big Spender’ introduction by Warren Mitchell (2:49) ‘Abduction’ introduction by Wanda Ventham (5:07)

Video

Network’s promotional material highlights the fact that all of the episodes, bar ‘Ringer’, have been ‘newly transferred, graded and painstakingly restored […] from the original A/B negatives’. In the case of ‘Ringer’, the negative was unavailable and so for that episode a film print was used as the source. ‘Ringer’ looks noticeably worse for wear than the other episodes in this set, but it still looks impressive. Shot entirely on 16mm, as noted above, The Sweeney looks very handsome on this release. The episodes look filmlike and play to the format’s strengths. Contrast levels are strong, and throughout the series there is the natural grain that a viewer should expect from material shot on 16mm. The presentation of this first series certainly surpasses any of the currently available DVD releases. The episodes are presented in 1080i, encoded with the AVC codec. All of the episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 1.33:1, and the break bumpers are intact.

Audio

For each episode, viewers are presented with the option of either a new DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix or the original mono mix (via a two-channel Dolby Digital track). Both of these are consistent and clear, although purists will want to opt for the mono track. Nevertheless, the alternative surround mix is neither showy nor intrusive. The episodes also feature English subtitles.

Extras

The discs are packed with plenty of extras, all of which are ported over from Network’s 2005 DVD release. Audio commentaries are provided for ‘Ringer’ (with Dennis Waterman, Garfield Morgan, writer Trevor Preston and editor Chris Burt), ‘Thin Ice’ (with producer Ted Childs, writer Troy Kennedy Martin and director Tom Clegg), ‘Night Out’ (one with director David Wickes and assistant director Bill Westley; and another with producer Ted Childs and writer Troy Kennedy Martin) and ‘Abduction’ (with Waterman, Morgan, Preston and Clegg). Introductions are also provided for ‘Queen’s Pawn’ (with Tony Selby), ‘The Placer’ (with John Forgeham), ‘Cover Story’ (with Prunella Gee), ‘Golden Boy’ (with Dudley Sutton), ‘Stoppo Driver’ (with Billy Murray), ‘Big Spender’ (with Warren Mitchell) and ‘Abduction’ (with Wanda Vetham). Disc one contains a twelve minute-long interview with Ian Kennedy Martin, which focuses on the development of the series. The first disc also contains a reconstructed version of the titles sequence using the original monochrome stills that were, in the finished titles sequence, tinted blue.

Overall

As noted above, The Sweeney has become an iconic show within popular culture. At times, it’s been unfairly represented as a kitsch show and chauvinistic show; but a closer look reveals a series that was often a solemn examination of policework in a decade that saw the fallout of a series of scandals involving corruption within London’s Metropolitan Police. Attentive viewers will notice how frequently episodes of The Sweeney defy convention, ending on a bittersweet note or allowing the villains to escape outright. It’s a gritty, exciting series, and this Blu-ray release of the first thirteen episodes is a fan’s dream come true. As noted above, The Sweeney has become an iconic show within popular culture. At times, it’s been unfairly represented as a kitsch show and chauvinistic show; but a closer look reveals a series that was often a solemn examination of policework in a decade that saw the fallout of a series of scandals involving corruption within London’s Metropolitan Police. Attentive viewers will notice how frequently episodes of The Sweeney defy convention, ending on a bittersweet note or allowing the villains to escape outright. It’s a gritty, exciting series, and this Blu-ray release of the first thirteen episodes is a fan’s dream come true.

References: Bignell, Jonathan, 2004: An Introduction to Television Studies. London: Routledge Clarke, Alan, 1992: ‘“You’re nicked!”: Television police series and the fictional representation of law and order’. In: Strinati, Dominic & Wagg, Stephen, 1992: Come on Down?: Popular Media Culture in Post-War Britain. London: Taylor & Francis: 232-53 Delaney, Sean, 2003: ‘TV Police Drama’. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/445716/index.html Fairclough, Robert & Kenwood, Mike, 2002: Sweeney! The Official Companion. London: Reynolds & Hearn Johnson, Catherine & Turnock, Robert, 2005: ITV Cultures: Independent Television Over Fifty Years.. London: McGraw-Hill Leishman, Frank & Mason, Paul, 2001: Policing and the Media: Facts, Fictions and Factions.. London: Willan Publishing Mawby, Rob C., 2007: ‘Criminal Investigation and the Media’. In: Newburn, Tim et al, 2007 (eds): Handbook of Criminal Investigation.. London: Willan Publishing: 146-69 Rolinson, David, 2011: ‘From “The Blue Lamp” to “The Black and Blue Lamp”: The Police in TV Drama’. [Online.] http://www.britishtelevisiondrama.org.uk/?p=1429 Strinati, Dominic & Wagg, Stephen, 1992: ‘Introduction: Come on Down? – popular culture today’. In: Strinati, Dominic & Wagg, Stephen, 1992: Come on Down?: Popular Media Culture in Post-War Britain. London: Taylor & Francis: 1-8 Waterman, Dennis, 2002: ‘Foreword’. In: Fairclough, Robert & Kenwood, Mike, 2002: Sweeney! The Official Companion. London: Reynolds & Hearn: 6-7 For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|