|

|

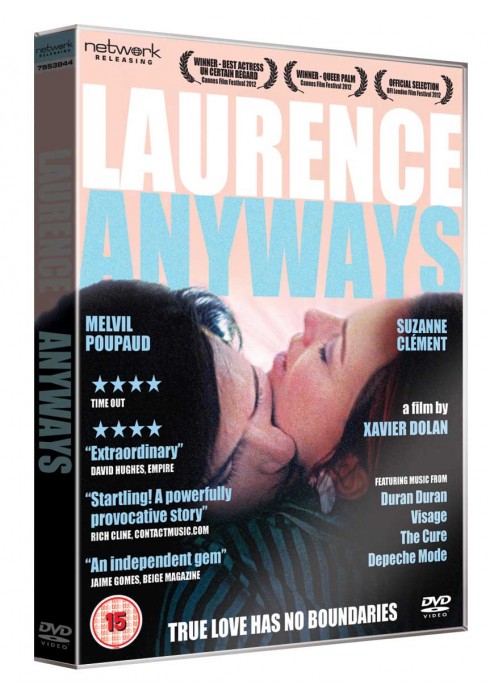

Laurence Anyways

R0 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th March 2013). |

|

The Film

Laurence Anyways (Xavier Dolan, 2012) Laurence Anyways (Xavier Dolan, 2012)

Films about transgender issues are relatively few and far between. Films which feature a positive representation of transgender characters are even more rare. Most negatively, some of the films which feature transgender characters use transgenderism as an index of deviance: for example, in Transgender Nation (1994), Gordene Olga MacKenzie states that films such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (1980) and Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1991), all of which feature murderers who also happen to be trans people, ‘disproportionately portray transgenderists and cross-dressers as “berserk murderers” on a rampage. This demeaning and inaccurate stereotype of the male-to-female transgenderist “dressed to kill” reflects the cultural fear that the “dressed to kill” transgenderist will annihilate the bipolar gender system’ (106). Other films use transgenderism as little more than a camp spectacle: Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) features a ‘reveal’ towards the end of the film that one of the characters is in fact transgendered, in a moment that is intended to be both shocking and funny; likewise, Michael Sarne’s Myra Breckenridge (1970), which famously features Raquel Welch as a transgendered character, is little more than an outrageous exercise in excess. On the other hand, a handful of films have contained more sympathetic and complex depictions of transgenderists, although some of these – such as Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda (1953) – have been appropriated as camp. For a while, the success of Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game in 1992 seemed to push transgender issues into cinema’s limelight, and during the 1990s a number of films focused on trans people. Some of these films, such as Orlando (Sally Potter, 1992) and Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999), offered a serious examination of transgender issues and identity politics; other films, like The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994), delivered a humourous but sympathetic depiction of their transgender characters. Laurence Anyways, Xavier Dolan’s third film following I Killed My Mother (2009) and Heartbeats (2010), focuses on a transgender character: Laurence Alia (Melvil Poupaud) begins the film as a university lecturer, and by the end of the narrative he has both become a successful poet and made the journey from male to female. The film is long (just shy of three hours) and within its narrative approximately ten years pass. Dolan uses an effective framing device: the film is bookended by an interview conducted with Laurence, now a successful poet, in the diegetic present. In the opening sequence, this interview plays out over a black screen; as the film progresses, we see snippets of the interview, which a title card tells us takes place in a restaurant in Montreal in 1999, onscreen. Later, we see that Laurence, though successful in her writing career, is still treated with suspicion by those around her: the interviewer is cold towards Laurence upon their first meeting, but eventually warms to her. At the start of the film, the interviewer asks, ‘What are you looking for, Laurence Alia?’ Laurence responds: ‘Listen, I’m looking for a person who understands my language and speaks it. A person who, without being a pariah, will question not only the rights and value of the marginalised, but also those of the people who claim to be “normal”’.  The early scenes establish Laurence’s life as restrictive and subjected to the prejudices of others: following the offscreen interview that opens the film, we see a room bathed in soft light that, thanks to the square-ish compositions (Dolan elected to shoot this film in the old Academy ratio of 1.37:1), almost seems like a prison cell. We are shown a shot of a bedroom; then a shot of a kitchen. A door closes, the camera dollying in for a close-up of its handle. A woman (Laurence) walks into a room. A series of close-ups of people on the street, gazing into the camera, follow; we are seeing from Laurence’s point-of-view as she walks down the street. The faces of the people she encounters betray their emotions: some stare at her (and us) suspiciously, some angrily, some questioningly, some disapprovingly. Others point rudely. Their reactions underscore social attitudes towards those who step outside the gender norm, and the audience sees their reactions to Laurence from her perspective: Dolan cleverly inverts the gaze of the camera in this sequence, and we are encouraged to empathise with Laurence as she is treated as an outsider or freak by the gaze of these people. The early scenes establish Laurence’s life as restrictive and subjected to the prejudices of others: following the offscreen interview that opens the film, we see a room bathed in soft light that, thanks to the square-ish compositions (Dolan elected to shoot this film in the old Academy ratio of 1.37:1), almost seems like a prison cell. We are shown a shot of a bedroom; then a shot of a kitchen. A door closes, the camera dollying in for a close-up of its handle. A woman (Laurence) walks into a room. A series of close-ups of people on the street, gazing into the camera, follow; we are seeing from Laurence’s point-of-view as she walks down the street. The faces of the people she encounters betray their emotions: some stare at her (and us) suspiciously, some angrily, some questioningly, some disapprovingly. Others point rudely. Their reactions underscore social attitudes towards those who step outside the gender norm, and the audience sees their reactions to Laurence from her perspective: Dolan cleverly inverts the gaze of the camera in this sequence, and we are encouraged to empathise with Laurence as she is treated as an outsider or freak by the gaze of these people.

The film takes us back to 1989 (’10 Years Earlier’, a title card tells us; whilst later the precise year is identified by a calendar that is shown onscreen), and Laurence has fun in a new relationship with his girlfriend Frederique (Suzanne Clément) – whose preferred name ‘Fred’ seems another intentional swipe at gender conventions. At work, Laurence is already shown to be unconventional: teaching literature, he asserts to his class that ‘Proust describes too much: three hundred pages to tell us that Tutur fucks Tatave is too much’. Phrasing a question that will echo with the struggles we see him encountering later in the film and especially in the interview that frames the main narrative, Laurence asks his class a rhetorical question, ‘Can one’s writings, therefore, be great enough to exempt one from the rejection and ostracism that affect people who are different?’    Shortly after, Dolan offers another clever subversion of audience expectations when Laurence is depicted gazing surreptitiously at his female students (close-ups of his face as he gazes offscreen are intercut with shots of his female students). One of the students even returns his covert gaze directly, and Dolan holds the shot (and the actress’ gaze at Laurence, who is offscreen) to suggest her curiosity or sexual interest in Laurence. Conventional ideas about the male gaze (and the Kuleshov effect) would suggest Laurence is gazing lustfully at these young women. However, a shot from behind Laurence, as he rubs his hand across the back of his neck, reveals that he has placed paperclips on the tips of his fingers in order to mimic the young women he is watching; his gaze is thus revealed to be one of envy rather than lust. Dolan’s clever queering of the straight gaze takes place throughout the film, and is one of the strongest delights of Laurence Anyways.  Gordene Olga MacKenzie asserts that one of the most common mistakes mainstream films make is to confuse transgenderism with homosexuality: ‘mainstream depictions of transgenderists and cross-dressers are often confused with gay characters, due to the director’s ignorance or intent to confuse sex and gender’ (op cit.: 106). Dolan’s Laurence Anyways offers a complex examination of identity politics that avoids such stereotypes and in fact interrogates them in the sequence in which Laurence reveals to Fred his desire to live as a woman. Growing increasingly tired of Fred’s flippant behaviour whilst their car is stuck in a car wash (a strong symbol of entrapment and pressure), Laurence screams at Fred dramatically: ‘Just shut your fucking mouth [….] I have to tell you something! It’s very important! I have to tell you! […] I’ll die if I don’t […] I’m going to die’. Dolan elliptically cuts to a scene in Laurence’s home. Fred returns. She has been away, presumably digesting Laurence’s revelation. ‘Why didn’t you tell me you are gay?’, she asks Laurence. ‘I’m not gay, Fred’, he protests. ‘You’re a fag! You’re gay! It’s not the end of the world’, she tells him ironically. Laurence protests, trying to tell Fred that he feels like he has been ‘stealing someone’s life [….] The life of the woman I was born to be’. ‘Everything I love about you, you hate’, Fred responds: ‘So everything we’ve been through is nothing?’ ‘My life isn’t real. I’m on hold’, Laurence concludes. Gordene Olga MacKenzie asserts that one of the most common mistakes mainstream films make is to confuse transgenderism with homosexuality: ‘mainstream depictions of transgenderists and cross-dressers are often confused with gay characters, due to the director’s ignorance or intent to confuse sex and gender’ (op cit.: 106). Dolan’s Laurence Anyways offers a complex examination of identity politics that avoids such stereotypes and in fact interrogates them in the sequence in which Laurence reveals to Fred his desire to live as a woman. Growing increasingly tired of Fred’s flippant behaviour whilst their car is stuck in a car wash (a strong symbol of entrapment and pressure), Laurence screams at Fred dramatically: ‘Just shut your fucking mouth [….] I have to tell you something! It’s very important! I have to tell you! […] I’ll die if I don’t […] I’m going to die’. Dolan elliptically cuts to a scene in Laurence’s home. Fred returns. She has been away, presumably digesting Laurence’s revelation. ‘Why didn’t you tell me you are gay?’, she asks Laurence. ‘I’m not gay, Fred’, he protests. ‘You’re a fag! You’re gay! It’s not the end of the world’, she tells him ironically. Laurence protests, trying to tell Fred that he feels like he has been ‘stealing someone’s life [….] The life of the woman I was born to be’. ‘Everything I love about you, you hate’, Fred responds: ‘So everything we’ve been through is nothing?’ ‘My life isn’t real. I’m on hold’, Laurence concludes.

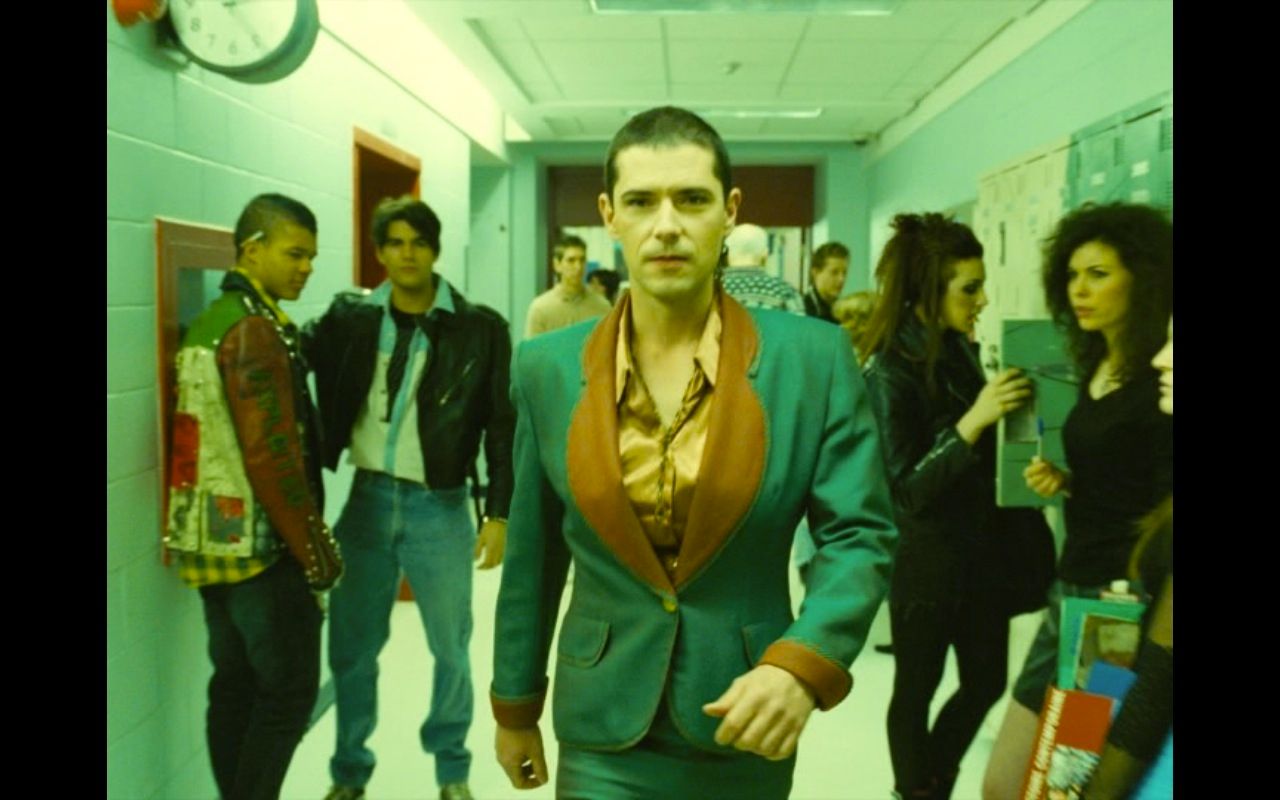

When Laurence finally plucks up the courage to go to work as a woman, he finds that his students are more accepting of his new identity than many of the others in his life, including his parents – from whom he is subtly alienated. As he enters his classroom, wearing women’s clothes, the students are silenced through shock. The camera dollies in for a close-up of Laurence’s face in a moment of triumph, as one of the students breaks the silence to ask a simple question about the essay they have been set. No remarks are made about Laurence’s new appearance, and shortly after this Laurence is shown, in a striking tracking shot, striding through the hallways of the institution; his dress is feminine, but his gate is unmistakeably masculine. Michel Lafortune (Yves Jacques), Laurence’s supervisor, meets him at lunch. ‘Is it a revolt?’, Lafortune asks Laurence, to which Laurence replies, ‘No, Sire. It is a revolution’, quoting the Duke de la Rochefoucauld’s comments to Louis XVI about the overthrow of the Bastille. However, Laurence’s managers are less sympathetic, and soon Laurence is called into a meeting. They claim that they have received a complaint about Laurence but assure him that his teaching is not under question. It is revealed that an article has been written about Laurence in which transexuality is labelled a ‘mental illness’. Laurence is to be dismissed. ‘What about justice?’ Laurence asks. ‘What about it? It’s fucked’, he’s told. Laurence is fired but is dissuaded from suing: ‘In short, I should thank you for the gift of unemployment because, silly me, who needs an income when you work in the arts. Is that right?’, Laurence notes dryly.  Laurence’s firing from his job provides him with the catalyst he needs in order to pursue his poetry seriously. However, at the same time his relationship with Fred begins to deteriorate. Although Fred notes to Laurence that ‘The moment I met you, I knew I was in for something extraordinary’, she struggles to cope with Laurence’s transformation and doubts his sexuality. Nevertheless, when Laurence is ridiculed by a waitress in a restaurant, Fred vocally comes to his defense. Nevertheless, the end of Laurence and Fred’s relationship comes when Fred makes the decision to sleep with other men. ‘How many times?’, Laurence asks Fred. ‘Five or six’, she tells Laurence. ‘Our love wasn’t “safe”, but it wasn’t dumb’, Laurence reminds Fred. ‘Why are you dressed like this? Why? Why not normal, like a woman?’, she asks Laurence in retaliation before admitting that she is still in love with him. Laurence’s firing from his job provides him with the catalyst he needs in order to pursue his poetry seriously. However, at the same time his relationship with Fred begins to deteriorate. Although Fred notes to Laurence that ‘The moment I met you, I knew I was in for something extraordinary’, she struggles to cope with Laurence’s transformation and doubts his sexuality. Nevertheless, when Laurence is ridiculed by a waitress in a restaurant, Fred vocally comes to his defense. Nevertheless, the end of Laurence and Fred’s relationship comes when Fred makes the decision to sleep with other men. ‘How many times?’, Laurence asks Fred. ‘Five or six’, she tells Laurence. ‘Our love wasn’t “safe”, but it wasn’t dumb’, Laurence reminds Fred. ‘Why are you dressed like this? Why? Why not normal, like a woman?’, she asks Laurence in retaliation before admitting that she is still in love with him.

The remainder of the film shows Laurence and Fred drifting in and out of each other’s orbits, in the town of Three Rivers in 1995, on the Isle of Black in 1996, and finally in Montreal in 1999. In their final meeting, Laurence tells Fred that she doesn’t ‘regret waking up in the morning and seeing the reflection I always dreamed of’, but says that what she regrets is that ‘even before I became a woman we were screwed [….] Before I was an outcast, we were outcasts already’. Fred reacts angrily, demanding that Laurence ‘come back to Earth’. ‘I don’t want to come back to Earth. I don’t give a fuck’, she says: ‘I won’t come down’. ‘Then stay up there’, she responds. The film ends with the final dissolution of Laurence and Fred’s relationship: they both sneak out of the restaurant where they have agreed to meet without saying goodbye. However, the bittersweet final scene ends either on a note of hope or a reminder of what has been lost, returning to Laurence and Fred’s first meeting, and the moment when their relationship began.  Whereas with Heartbeats, Dolan seemed enamoured by the stylistic techniques associated with Wong Kar-wai’s films, and Wong’s millennial romance In the Mood for Love (2000) in particular, in Laurence Anyways Dolan seems to offer a knowing pastiche of the glacial iciness and juxtapositions of locked-down cameras depicting almost painterly scenes with languorous tracking shots of Stanley Kubrick’s later films. The use of the almost square Academy ratio of 1.37:1 enhances the intimacy of many scenes, as does Dolan’s use of jump cuts and a handheld camera during some of the more intimate scenes of dialogue. These techniques almost give the film a semidocumentary appearance at times. Conversely, during other sequences Dolan creates some exquisite visual poetry: the film is filled with slow motion shots of characters wandering through city streets, thumping 1980s electro-pop music on the soundtrack, coats flapping in the breeze; strong primary colours are created through lighting gels; on the Isle of Black, Laurence and Fred wander in slow-motion through the streets, surrounded by the surreal sight of clothes fluttering down from the sky; Laurence and Fred’s final farewell shows them moving through the streets in slow-motion, autumn leaves falling cinematically from above; in another scene, Laurence is shown on the prow of a ship in yet another slow-motion shot that recalls the deeply memorable erotic scene in Patrice Leconte’s Le parfum d’Yvonne (1994), in which Sandra Majani stands against the railing of a paddle steamer and allows the breeze to catch her skirts - or possibly the now-iconic scene from James Cameron’s blockbuster Titanic (1997) in which Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet stand on the prow of the doomed Titanic. Like many of Kubrick’s films, Laurence Anyways oscillates between an intimate naturalism and heavy visual (and auditory) stylisation, and Dolan marries these two techniques with ease: Laurence Anyways is far more ‘showy’, but in some of the long and intimate scenes of dialogue between Fred and Laurence, which Dolan allows to play out at length, the film is slightly reminiscent of some of John Cassavetes’ films (Faces, 1968, in particular). Like some of Cassavetes’ pictures (Faces, the 1974 film A Woman Under the Influence) Laurence Anyways is centred on the strange tensions that exist between two people who clearly love one another but find themselves attracted and repelled in equal measure. Aside from the issues of identity politics, in this film Dolan seems to foreground the impossibility of love and the deceptive nature of desire; these are themes that are also at the heart of his second film, Heartbeats. Whereas with Heartbeats, Dolan seemed enamoured by the stylistic techniques associated with Wong Kar-wai’s films, and Wong’s millennial romance In the Mood for Love (2000) in particular, in Laurence Anyways Dolan seems to offer a knowing pastiche of the glacial iciness and juxtapositions of locked-down cameras depicting almost painterly scenes with languorous tracking shots of Stanley Kubrick’s later films. The use of the almost square Academy ratio of 1.37:1 enhances the intimacy of many scenes, as does Dolan’s use of jump cuts and a handheld camera during some of the more intimate scenes of dialogue. These techniques almost give the film a semidocumentary appearance at times. Conversely, during other sequences Dolan creates some exquisite visual poetry: the film is filled with slow motion shots of characters wandering through city streets, thumping 1980s electro-pop music on the soundtrack, coats flapping in the breeze; strong primary colours are created through lighting gels; on the Isle of Black, Laurence and Fred wander in slow-motion through the streets, surrounded by the surreal sight of clothes fluttering down from the sky; Laurence and Fred’s final farewell shows them moving through the streets in slow-motion, autumn leaves falling cinematically from above; in another scene, Laurence is shown on the prow of a ship in yet another slow-motion shot that recalls the deeply memorable erotic scene in Patrice Leconte’s Le parfum d’Yvonne (1994), in which Sandra Majani stands against the railing of a paddle steamer and allows the breeze to catch her skirts - or possibly the now-iconic scene from James Cameron’s blockbuster Titanic (1997) in which Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet stand on the prow of the doomed Titanic. Like many of Kubrick’s films, Laurence Anyways oscillates between an intimate naturalism and heavy visual (and auditory) stylisation, and Dolan marries these two techniques with ease: Laurence Anyways is far more ‘showy’, but in some of the long and intimate scenes of dialogue between Fred and Laurence, which Dolan allows to play out at length, the film is slightly reminiscent of some of John Cassavetes’ films (Faces, 1968, in particular). Like some of Cassavetes’ pictures (Faces, the 1974 film A Woman Under the Influence) Laurence Anyways is centred on the strange tensions that exist between two people who clearly love one another but find themselves attracted and repelled in equal measure. Aside from the issues of identity politics, in this film Dolan seems to foreground the impossibility of love and the deceptive nature of desire; these are themes that are also at the heart of his second film, Heartbeats.

The film runs for 161:14 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. This is quite unusual for modern films but not without precedents: recent films shot in this aspect ratio include The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011), Meek’s Cutoff (Kelly Reichardt, 2010), Gus Van Sandt’s Elephant (2003) and Andrea Arnold’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights (2011). The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. This is quite unusual for modern films but not without precedents: recent films shot in this aspect ratio include The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011), Meek’s Cutoff (Kelly Reichardt, 2010), Gus Van Sandt’s Elephant (2003) and Andrea Arnold’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights (2011).

Dolan uses the almost square Academy frame to enhance the intimacy in some of the scenes between Fred and Laurence. Some of the photography is tremendously good – especially the shots of the interiors of rooms. The almost square frame is used to exception, making these rooms seem like prisons. Dolan also uses jump cuts and a handheld camera to create a semidocumentary style, which at times is placed in juxtaposition with more poetic and expressionistic sequences. Sometimes Dolan bathes the image in deep primary colours – reds and blues, primarily. The transfer on this disc is very good. Colours are rich and deep, and contrast is handled nicely by the encode. However, given that the film has such a lush visual style, it’s hard not to consider how preferable a Blu-ray release would be.

Audio

The disc offers an option of a 5.1 surround track and a two-channel stereo track. Both tracks offer a rich soundscape, but the 5.1 track showcases some of the amazing sound design, with the 1980s pop music tracks being particularly foregrounded. Dialogue is in French, with some English passages. English subtitles are optional and do not cover the English dialogue.

Extras

Extras are limited to the film’s trailer (2:43) and an interview with the film’s stars, Suzanne Clement and Melvil Poupaud (13:52). Start-up trailers (skippable): I Killed My Mother, Heartbeats, No (4:20).

Overall

There’s considerable depth to Xavier Dolan’s third film, which deals with some very complex issues and shows a maturity in terms of its depiction of relationships that belies Dolan’s youth (at the time of this release, Dolan is just 24). Dolan is also proving himself to be something of an auteur: Laurence Anyways revisits some of the obsessions of Dolan’s previous two films (Hearbeats and I Killed My Mother), including an obsession with retro-fashions, a focus on dysfunctional relationships, the use of slow-motion tracking shots, and a measured use of sound and, in particular, carefully-selected retro-pop music. Familiar faces from Dolan’s previous films crop up in Laurence Anyways too: one of the stars of Heartbeats, Monia Chokri excels here in playing yet another brash, catty and self-absorbed woman, Fred’s sister Stéfanie. ‘Who’s the purple gaylord, Liberace’s interior decorator?’, Stéfanie asks Fred in the kitchen at Laurence’s 35th birthday party, and later she spitefully refers to Laurence as ‘Tranny Poppins’. There’s considerable depth to Xavier Dolan’s third film, which deals with some very complex issues and shows a maturity in terms of its depiction of relationships that belies Dolan’s youth (at the time of this release, Dolan is just 24). Dolan is also proving himself to be something of an auteur: Laurence Anyways revisits some of the obsessions of Dolan’s previous two films (Hearbeats and I Killed My Mother), including an obsession with retro-fashions, a focus on dysfunctional relationships, the use of slow-motion tracking shots, and a measured use of sound and, in particular, carefully-selected retro-pop music. Familiar faces from Dolan’s previous films crop up in Laurence Anyways too: one of the stars of Heartbeats, Monia Chokri excels here in playing yet another brash, catty and self-absorbed woman, Fred’s sister Stéfanie. ‘Who’s the purple gaylord, Liberace’s interior decorator?’, Stéfanie asks Fred in the kitchen at Laurence’s 35th birthday party, and later she spitefully refers to Laurence as ‘Tranny Poppins’.

‘You hope to end the divide between the normal and the marginal?’, Laurence’s interviewer asks her sarcastically. ‘We’re about to enter a new millennium’, Laurence adds: ‘Why not wish for real change?’ She asserts, ‘I’m about to live the last half of a woman’s life’. ‘All women do, eventually’, the interviewer notes. ‘Yes, but the last half’s nothing without the first’, Laurence reminds her. This tension between the promise of the future and the loss of the past is at the heart of Laurence Anyways: in this film (and arguably, Dolan’s body of work as a whole), hope is always mitigated by despair, and Laurence’s transformation into the woman he always desired to be is balanced by the loss of the woman he desires to have. It’s a bittersweet worldview, and Dolan is clearly growing as a filmmaker. Laurence Anyways is highly recommended. Laurence Anyways is available individually, or as part of Network's Xavier Dolan boxed set La Folie d'Amour, which also includes I Killed My Mother and Heartbeats. References MacKenzie, Gordene Olga, 1994: Transgender Nation. London: Popular Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|