|

|

House in Nightmare Park (The) AKA Crazy House AKA Night of the Laughing Dead

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (2nd April 2013). |

|

The Film

The House in Nightmare Park (Peter Sykes, 1973)  Frankie Howerd’s career in radio, television and film comedy spanned four decades. During that period, Howerd experienced several low points: comedy writers Ray Galton and Alan Simpson once commented that, as their work as writers for Tony Hancock’s long-running series Hancock (BBC, 1956-61) came to a close in 1961, they pitched an idea for a sitcom featuring Howerd to the BBC’s then-Head of Light Entertainment, Tom Sloane. Sloane told them, ‘No, you don’t want to do that, [Howerd is] finished. We did a series with him [Frankly Howerd] and had terrible figures. I don’t think we want that’ (Webber, 2006: 66). However, Howerd’s popularity was revived following his appearance at Peter Cooke’s Establishment Club in 1962. Howerd was unafraid of playing the fool, and thanks to a script from Eric Sykes, Johnny Speight and the team of Galton and Simpson, he found a new audience in a performance that ‘play[ed] up the incongruity of the artist and the venue, painting Howerd as out of touch, so that the satirical punches had an even greater effect when they came’ (Barfe, 2006: 170). Frankie Howerd’s career in radio, television and film comedy spanned four decades. During that period, Howerd experienced several low points: comedy writers Ray Galton and Alan Simpson once commented that, as their work as writers for Tony Hancock’s long-running series Hancock (BBC, 1956-61) came to a close in 1961, they pitched an idea for a sitcom featuring Howerd to the BBC’s then-Head of Light Entertainment, Tom Sloane. Sloane told them, ‘No, you don’t want to do that, [Howerd is] finished. We did a series with him [Frankly Howerd] and had terrible figures. I don’t think we want that’ (Webber, 2006: 66). However, Howerd’s popularity was revived following his appearance at Peter Cooke’s Establishment Club in 1962. Howerd was unafraid of playing the fool, and thanks to a script from Eric Sykes, Johnny Speight and the team of Galton and Simpson, he found a new audience in a performance that ‘play[ed] up the incongruity of the artist and the venue, painting Howerd as out of touch, so that the satirical punches had an even greater effect when they came’ (Barfe, 2006: 170).

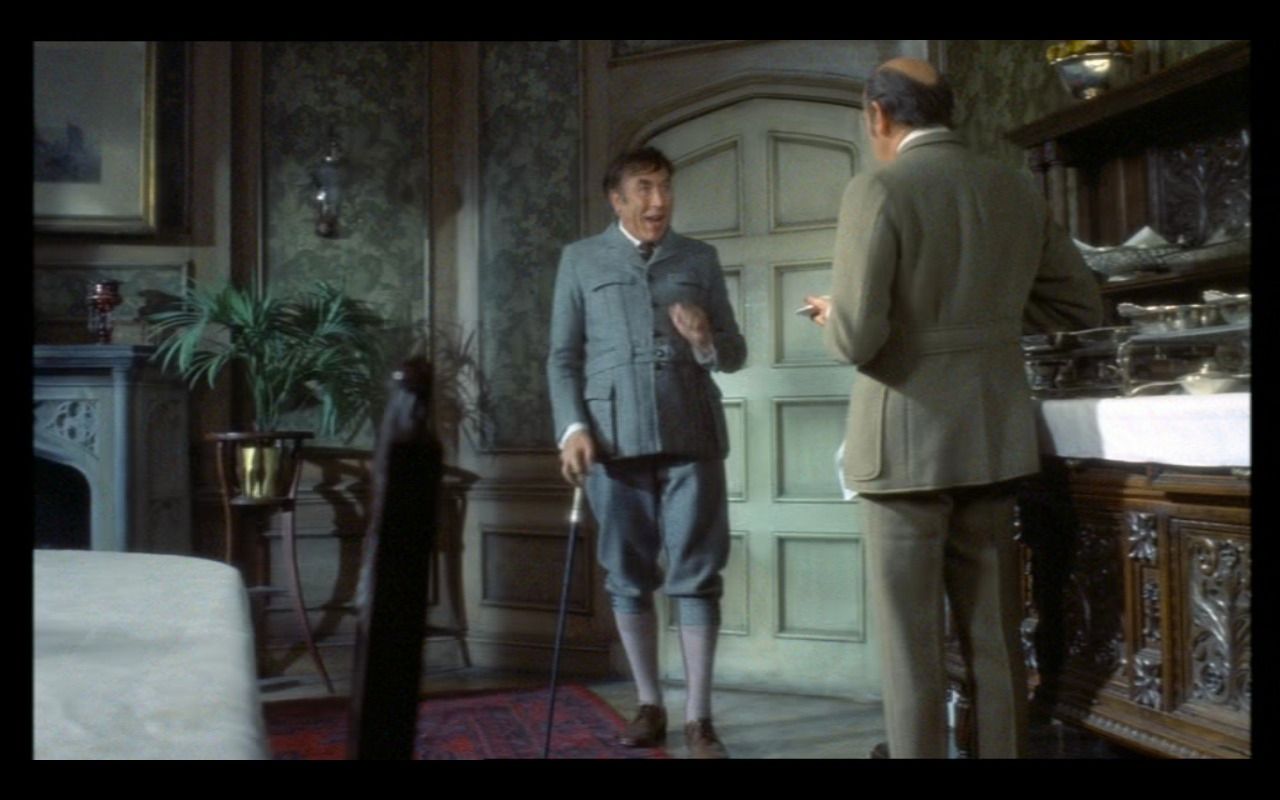

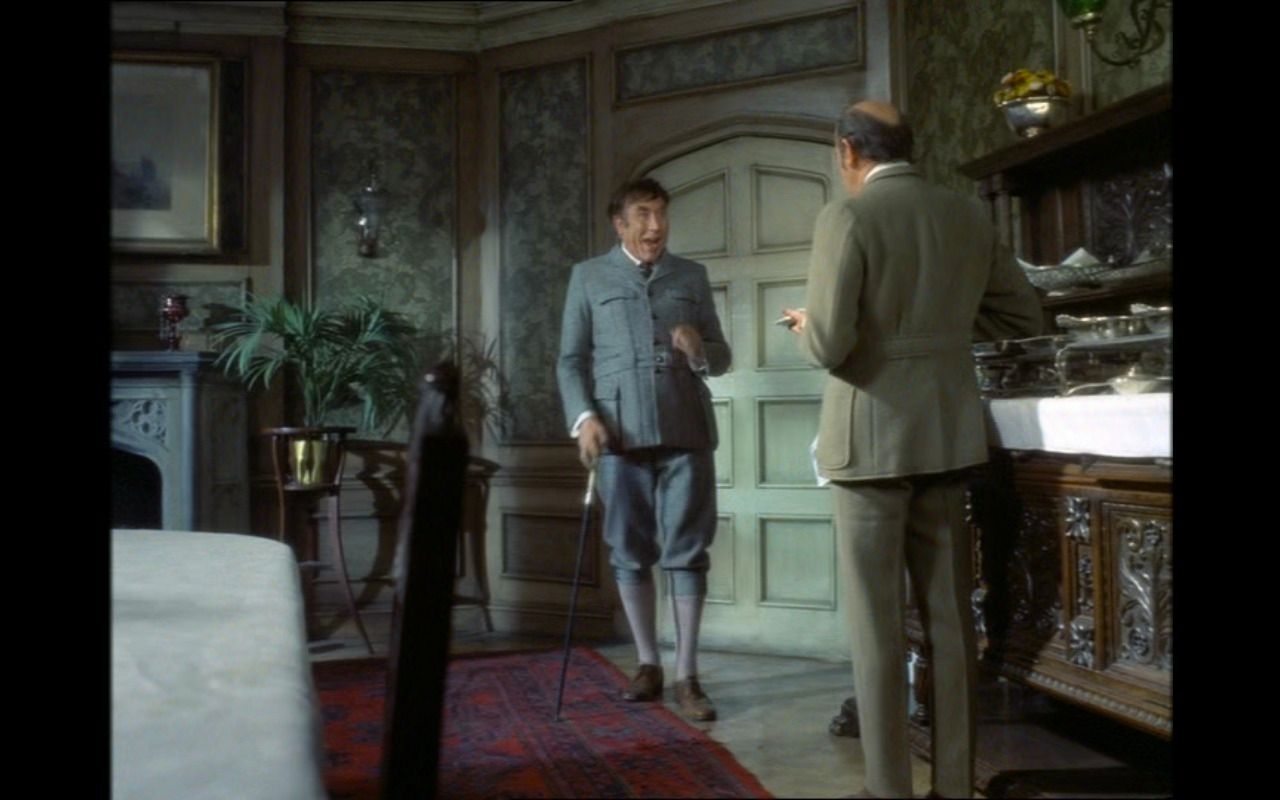

More television work followed, and the success of Howerd’s performance in the London version of the stage musical A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1963-5) led to Howerd being associated with comedy roles set in the historical past; and Howerd’s 1969 sitcom Up Pompeii! (BBC, 1969-70), often cited as influenced by Howerd’s role in …Forum, saw a further revival of Howerd’s career and consolidated some of the techniques that Howerd would carry over into some of his later work on television and in films, including the use of anachronistic comments for comic effect, Howerd’s droll asides to the audience and his mock-censuring of the viewers for ‘misinterpreting’ the double entendres that peppered the scripts. The House in Nightmare Park carries some of these traits over: the film is set in 1907, and Howerd once again gets to play a fool (in this case, egotistical actor Foster Twelvetrees, who exhibits an incredible amount of delusion regarding his acting talent) who nevertheless demonstrates moments of clarity throughout the narrative. The film also features Howerd making his trademark asides to the audience, although these are downplayed and without the laugh track of Up Pompeii! sometimes fall a little flat. The film features Howerd playing a role that is both dramatic and comic; as Kim Newman (2006) has observed, in many of his other roles (eg, Up Pompeii and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum), Howerd ‘essentially does his own act while the plot gets on with itself in the background, but here he actually plays a role, albeit one written to order’ (108). The narrative itself, scripted by Clive Exton and Terry Nation, draws heavily on the 1939 adaptation of John Willard’s 1922 play The Cat and the Canary (directed by Elliott Nugent), which starred Bob Hope as a stage actor, one of a group of relatives of the deceased Cyrus Norman who are called to Norman’s house for the reading of his will. The script for this 1939 version of Willard’s play foregrounded its comic elements and set the groundwork for the significant number of parodies of the ‘old dark house’ thriller that were to follow: Bruce G Hallenbeck has stated that The Cat and the Canary ‘raised the bar for all future comedy-horror films’ and is ‘the movie in which Hope created his “cowardly” hero role, the wisecracking man of the world who uses quips to fight off his fear. The story features all of the usual clichés: sliding panels, clutching hands, lights that turn themselves on and off, eerie wails and shadows galore’ (2009: 25). Hallenbeck also notes that ‘the 1939 version [of Willard’s play] takes an almost post-modern approach. Cast as a stage and radio actor, Hope continually comments on the action throughout the film as if he were performing it in a play [….] Hope’s winking performance assures us that, although we may have moments of fright and shock, everything will turn out just fine in the end’ (ibid.: 26). Nugent’s The Cat and the Canary proved to be the model for a number of subsequent horror comedies, including Pat Jackson’s excellent 1961 film What a Carve Up!, with Kenneth Connor and Sid James playing two characters who are invited to an ‘old dark house’ for the reading of a will only to find that the other guests are gradually murdered one-by-one. The House in Nightmare Park similarly takes The Cat and the Canary as its model, featuring a similar premise and an equally similar use of a protagonist - who, like Hope's character in The Cat and the Canary is also an actor - who threatens to break the 'fourth wall'. Filmed at Shepperton Studios, with the titular house being played in exterior sequences by the Oakley Court Hotel on Windsor Road - familiar from a number of other horror films of the period (John Gilling’s The Plague of the Zombies, 1966; Freddie Francis’ Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny and Girly, 1970) - the film opens with Howerd’s character, Foster Twelvetrees, reading from Dickens’ Oliver Twist in a small hall. His audience are clearly disinterested: a boy blows a raspberry at Twelvetrees; another man is slumped in his seat, half-asleep; an elderly man nods off and begins to snore. The camera dollies across the audience to the smartly-dressed Stewart Henderson (Ray Milland) as he wraps a white scarf around his hand – a subtly-threatening action that will later be echoed when Twelvetrees encounters Henderson’s mother. Signifiers of wealth (the scarf, a top hat, a clean morning coat) establish Henderson as different from the other members of the audience.  Henderson leaves the hall and, exiting the building, walks towards a woman, telling her, ‘It is he. Incredible’. The opening titles play out, and as they end we see a horse rearing in an intimidating low-angle close-up. The driver of the carriage which the horse is pulling throws Twelvetrees’ baggage to the ground near Twelvetrees’ feet. ‘Where’s the house?’, Twelvetrees asks the driver. ‘Half a mile, up the drive’, is the response. ‘I paid you to take me to the house’, Twelvetrees protests. ‘Half a mile’s close enough for me’, the driver tells him, echoing the reticence of similar carriage drivers in films from Nosferatu (F W Murnau, 1922) to Dracula: Prince of Darkness (Terence Fisher, 1966). ‘I hope yer whip shrivels’, Twelvetrees mutters as the carriage disappears into the distance. Henderson leaves the hall and, exiting the building, walks towards a woman, telling her, ‘It is he. Incredible’. The opening titles play out, and as they end we see a horse rearing in an intimidating low-angle close-up. The driver of the carriage which the horse is pulling throws Twelvetrees’ baggage to the ground near Twelvetrees’ feet. ‘Where’s the house?’, Twelvetrees asks the driver. ‘Half a mile, up the drive’, is the response. ‘I paid you to take me to the house’, Twelvetrees protests. ‘Half a mile’s close enough for me’, the driver tells him, echoing the reticence of similar carriage drivers in films from Nosferatu (F W Murnau, 1922) to Dracula: Prince of Darkness (Terence Fisher, 1966). ‘I hope yer whip shrivels’, Twelvetrees mutters as the carriage disappears into the distance.

Twelvetrees arrives at the house to find it strangely abandoned. He hears a shriek upstairs, and canted angles and crash zooms establish something is awry. ‘They can stuff their five guineas: I’m off’, Twelvetrees mutters to himself. However, his departure is interrupted by Patel (John Bennett), the British-Asian manservant of the Henderson family. When Stewart Henderson makes an appearance, he shows Twelvetrees a bust of Kali. ‘Are you a Buddhist?’ Twelvetrees asks. ‘No’, Henderson protests, telling Twelvetrees that his family are converts to the Hindu faith. Henderson: ‘Kali Ma, the dark mother, the goddess of death and destruction. Note the bloodstained tongue, the entwining snake, the necklace of skulls, the matted hair’. ‘Well, I suppose St Francis of Assissi would seem a bit wishy-washy next to her’, Twelvetrees jokes. It is revealed that Twelvetrees has been invited to entertain the household during the Christmas period. Twelvetrees is gradually introduced to the other members of the Henderson family: Stewart’s mother (Aimée Delamain), his brothers Reggie (Hugh Burden) and Ernest (Kenneth Griffith), their wives Agnes (Ruth Dunning) and Jessica (Rosalie Crutchley) and Stewart’s niece Verity (Elizabeth MacLennan). As the narrative progresses, the reason for Twelvetrees’ presence in the Henderson household is revealed to be more complicated than it initially appeared: the wealthy patriarch Victor Henderson has passed away, and it appears that the only person who knows the location of the diamonds that Victor hid in the house, is Victor’s secret son – Twelvetrees. However, Twelvetrees is unaware of the fact that Victor is his father, and the Hendersons attempt to extract this knowledge from their unknowing, and unwitting, victim. Things become more complicated as members of the Henderson family are gradually murdered one-by-one… The film’s horror elements are surprisingly effective and refer back to a number of recognisable conventions of the genre. For example, the Henderson family’s past in India, and the presence of their Indian manservant Patel, recalls other British horror films which look to Britain’s colonial past and feature characters who have brought back some of the (usually invented and/or inaccurately-depicted) customs of the countries which were previously part of the British Empire. Kim Newman (2006) has asserted that the Anglo-Indian aspects of The House in Nightmare Park recall Conan Doyle’s 1892 story ‘The Adventure of the Speckled Band’ ‘and prefigures [Freddie Francis’ 1975 film] The Ghoul’ (108). There are also some similarities with John Gilling’s The Reptile (1966), which features a similarly morally-ambiguous ‘exotic’ manservant; and many of these narratives have their roots in W W Jacobs’ 1902 short story ‘The Monkey’s Paw’, in which a member of the British army returns from India with a monkey’s paw which is claimed to grant three wishes to its owner – both a blessing and a curse. This particular type of narrative, with its overt fear of the ‘exotic’, was later parodied very effectively in ‘The Curse of the Claw’, an episode of Michael Palin and Terry Jones’ Ripping Yarns (BBC, 1976-9). The House in Nightmare Park plays most of these elements in a perhaps unexpectedly ‘straight’ manner, downplaying the comic potential of this specific scenario. Howerd’s trademark asides are also uncharacteristically downplayed. Kim Newman has observed that in the film, ‘Howerd’s delivery is toned-down to suit the ominous mood, with his frame-breaking trademark asides to the audience […] played as self-involved mutterings rather than shouted to the back stalls’ (op cit.: 108). Nevertheless, the pompous Twelvetrees, blessed with an inflated perception of his own talents as an actor, is a recognisable character from Howerd’s repertoire. Twelvetrees is arrogant but also curiously innocent: like other Howerd characters, he’s something of a man-child. As with some of Howerd’s other screen characters, there’s an incongruity between Howerd’s age and appearance and the age of the character he’s playing. Howerd was of a similar age to Milland, Burden and Griffith, the actors playing Twelvetrees’ uncles in the film; and in one sequence the incongruity between Howerd’s age and his character is foregrounded when Twelvetrees, on his first night in the house, decorates his room with pictures of himself, gazes into the mirror and quips, ‘Hmm, not bad for 32’. Elsewhere, Howerd’s familiar innuendos are evident. In one sequence, Twelvetrees is shown in bed, dreaming and talking in his sleep: ‘Oh, Melanie, don’t. I’m saving myself for Miss Right. Oh, Melanie. It’s the knockers, Melanie’. He is awakened by knocking at the front door. ‘They won’t let you enjoy anything in this house. Oh well, another two minutes and I might have cheapened myself’, he mutters to himself. The next day, he takes a walk outside the house and finds Jessica Henderson tending to two rabbits. ‘Little bun buns! […] What a lovely pair. What beauties. May I stroke them? The, er, the rabbits, I mean’, Twelvetrees asks. Without speaking Jessica leaves. ‘Oh, dear. She’s taken umbrage’, Twelvetrees notes. He follows Jessica into the house and watches as she pushes the rabbits through a hole into another room which is separated from the room in which the pair stand by a wall-length pane of glass. Twelvetrees asks, ‘If you’ll forgive the crudity, they’re not going to play mummies and daddies, are they?’ He watches in increasing horror, eventually fainting, as a python appears and kills the rabbits. In a later sequence, as Howerd recites ‘Little Nell’, Verity screams and passes out. ‘It’s never gone that well before’, he asserts. He undoes the neck of her frock. ‘You swine, I’m going to thrash you within an inch of your life’, Ernest says. ‘I was just giving her me Little Nell’, Twelvetrees protests. Some sequences show a confident blending of horrific and comic elements, for which Sykes (and his director of photography Ian Wilson, who had also worked on Up Pompeii!) must be credited.  In what is arguably one of the most disturbing sequences in the film, the Hendersons perform for Twelvetrees, dressing up as dolls and dancing whilst Jessica sings ‘When the Dolls Dance’. The sequence is darkly amusing but also grotesque, thanks to the use of make-up and the filmmakers’ decision to shoot the performance using a wide-angle lens. ‘Oh, God’, Twelvetrees observes as the performance ends: ‘God knows what they do for an encore’. In what is arguably one of the most disturbing sequences in the film, the Hendersons perform for Twelvetrees, dressing up as dolls and dancing whilst Jessica sings ‘When the Dolls Dance’. The sequence is darkly amusing but also grotesque, thanks to the use of make-up and the filmmakers’ decision to shoot the performance using a wide-angle lens. ‘Oh, God’, Twelvetrees observes as the performance ends: ‘God knows what they do for an encore’.

The film has a curiously international aspect: as Kim Newman notes, the ‘selection of Peter Sykes as director and the casting of Welsh-born Hollywood star Ray Milland as the chief heavy suggests that [the filmmakers] had ambitions for the project beyond the domestic comedy market’ (op cit.: 108). It’s an interesting, amusing film, but it’s rarely laugh-out-loud funny: as Newman has stated, ‘[i]t’s a wryly amusing film rather than a hysterically funny one’ (ibid.). Partly, this could be down to the ways in which certain aspects of Howerd’s stage and screen persona are toned down here in service of the dramatic elements of the plot: as noted above, Howerd’s trademark asides are largely absent, and without the laughter of the studio audience they often fall a little flat. As Phil Hardy’s Aurum Film Encyclopedia (1985) observes in its entry on The House in Nightmare Park, ‘Howerd’s vaudeville comedy requires the giggling complicity of a live audience. On film, the limits of his range as a comic actor are painfully obvious, making him a buffoon instead of a comic’ (277). Nevertheless, there's plenty here for fans of Howerd to enjoy, and enthusiasts of horror films should also find The House in Nightmare Park's pastiche of the tropes of prior horror films enjoyable. The film runs for 91:58 mins (PAL)

Video

The House in Nightmare Park looks very good on this DVD from Network, much better than any previous releases. This is a very colourful transfer from a clean and clear master. Contrast levels are good.

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.68:1, with anamorphic enhancement. What's especially noticeable from this DVD release, thankfully in the film's original aspect ratio, is just how well-shot the picture is.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track, which is clean and audible throughout. Some of the dialogue can be a little unclear at times, but this is likely an issue with the sound quality of the original film rather than this specific presentation. Sadly, no subtitles are included.

Extras

Network have included a fullscreen (open-matte) version of the film (91:57) on the disc. This is an interesting, though arguably non-essential extra. Some screengrabs are below, to illustrate the differences between the fullscreen and widescreen versions of the film.

Other extras include the film’s trailer (2:59), a mute TV spot (0:29), a music suite (29:33) showcasing Harry Robinson’s effective score for the film, and an 8-page press brochure (stored on the disc as a PDF file accessible via a DVD-ROM drive).

Overall

The House in Nightmare Park is an enjoyable film, especially for fans of Howerd, but in heightening the drama of the narrative it downplays some of the more entertaining aspects of Howerd’s comic persona, and in highlighting Howerd’s presence it undermines some of the more dramatic elements of the narrative. Horror comedies are notoriously difficult to ‘get right’, and The House in Nightmare Park is no competition for its model, Nugent’s 1939 The Cat and the Canary – or even some of the other films influenced by Nugent’s film, such as Pat Jackson’s What a Carve Up! Nevertheless, it’s an entertaining little film, offering a hodge-podge of ideas that are recognisable from previous horror narratives. Fans of Howerd will find plenty to enjoy here, and Network’s presentation of the film on this DVD is very strong: it’s certainly the best presentation of the film to have been released to date. References: Barfe, Louis, 2008: Turned Out Nice Again: The Story of British Light Entertainment. London: Atlantic Books Hallenbeck, Bruce G, 2009: Comedy-Horror Films: A Chronological History, 1914-2008. London: McFarland Hardy, Phil, 1985: The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror. London: Aurum Press: 277-8 Newman, Kim, 2001: ‘The House in Nightmare Park’. In: Fenton, Harvey & Flint, David (eds), 2001: Ten Years of Terror. Surrey: FAB Press: 108-9 Webber, Richard, 2006: That Was the Decade That Was. London: Michael O’Mara Books, Ltd. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|