|

|

West of Zanzibar

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (9th April 2013). |

|

The Film

West of Zanzibar (Harry Watt, 1954)  Harry Watt’s West of Zanzibar (1954) is a sequel to the same director’s previous film Where No Vultures Fly (1951); both films feature Anthony Steel as Bob Payton, Kenyan game warden, a character loosely based on the real conservationist Mervyn Cowie. Focusing on Payton’s attempts to establish himself as a game warden in Africa and achieve his dream (a reserve where, as the title suggests, ‘no vultures fly’), Where No Vultures Fly had been based on extensive research and was rooted in fact: Scottish director Watt was, along with the Brazilian documentary filmmaker Alberto Cavalcanti, ‘largely responsible for [Ealing’s] switch to documentary realism after the fiasco of “Ships With Wings”, a ridiculously fictionalised story about the Ark Royal’ (Relph, 2009: 324). Watt’s The Overlanders (1946), a quasi-documentary film about drovers in Australia, ‘retained his documentary realism’ but, Michael Relph has argued, both West of Zanzibar and Where No Vultures Fly ‘were marred by the naivety of their fictional elements’ (ibid.). Harry Watt’s West of Zanzibar (1954) is a sequel to the same director’s previous film Where No Vultures Fly (1951); both films feature Anthony Steel as Bob Payton, Kenyan game warden, a character loosely based on the real conservationist Mervyn Cowie. Focusing on Payton’s attempts to establish himself as a game warden in Africa and achieve his dream (a reserve where, as the title suggests, ‘no vultures fly’), Where No Vultures Fly had been based on extensive research and was rooted in fact: Scottish director Watt was, along with the Brazilian documentary filmmaker Alberto Cavalcanti, ‘largely responsible for [Ealing’s] switch to documentary realism after the fiasco of “Ships With Wings”, a ridiculously fictionalised story about the Ark Royal’ (Relph, 2009: 324). Watt’s The Overlanders (1946), a quasi-documentary film about drovers in Australia, ‘retained his documentary realism’ but, Michael Relph has argued, both West of Zanzibar and Where No Vultures Fly ‘were marred by the naivety of their fictional elements’ (ibid.).

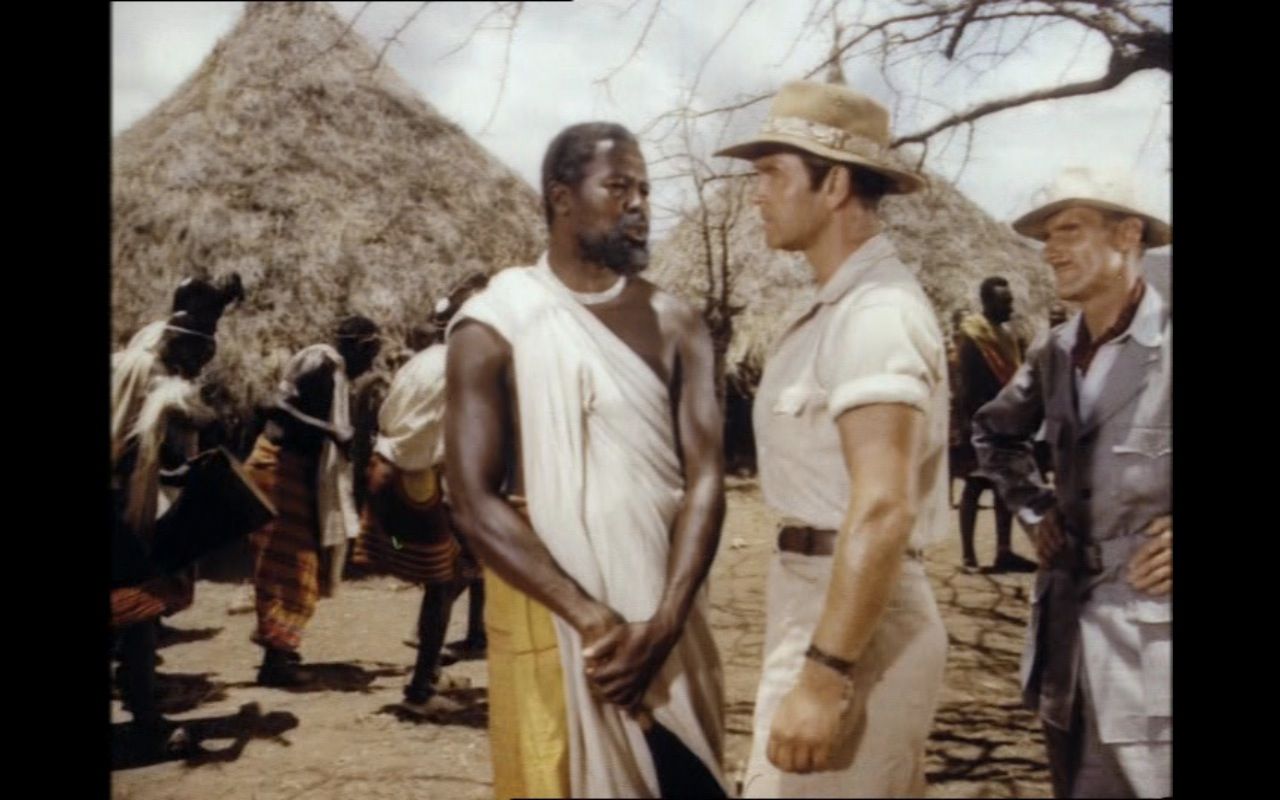

West of Zanzibar has been referred to as ‘an anti-climactic sequel’ to Where No Vultures Fly, which had ‘achieved a comparable robust U-certificate adventure quality, and a still greater box office success’ (Barr, 1998: 202). Charles Barr has asserted that West of Zanzibar, made with many of the same personnel as Where No Vultures Fly, ‘is much less “open”, technically and thematically’ (ibid.: 205). Paul Beeson’s excellent wildlife footage is still present, but much of the action takes place on sets or makes heavy use of back projection. The film’s narrative focuses on rural Kenyans who, following a severe drought, are forced to relocate to the coast and find themselves exploited by Arabic ivory poachers. (The Arabs are painted as the film’s villains, whilst the Kenyans are simply their ‘patsies’.) The film was banned by the Kenyan government: Charles Barr has said that ‘Watt’s amazement’ at the ban ‘was surely ingenuous: it takes the Africans’ side against exploitation, as [Watt] insists, but in a deeply paternalist way’ (op cit.: 205). The manipulation of the Galanas, the Kenyan tribe with which Payton is stationed, by the Arabic ivory traders refers back to an established trend in colonial films, in which ‘[n]ative unruliness had often been attributed at the cinema to interfering outsiders, particularly Russians, Germans and Arabs’ (Shaw, 2006: 51). James Chapman (2005) lists West of Zanzibar amongst the ‘colonial police fllms’ of the 1950s and 1960s, a subgenre which also included Harry Watt’s Where No Vultures Fly (215). Chapman notes that where 1930s films focusing on issues of empire ‘had been oriented principally towards the expansion of the Empire’, in the 1950s and the 1960s ‘the main theme had become one of defending the Empire’ (ibid.). Jeffrey Richards has stated that whereas in Where No Vultures Fly, Steel (‘the last of the Imperial actors’) was ‘protecting the wild-life of Kenya against poachers’, in West of Zanzibar he is given ‘a much more traditionally Imperial role’ (1973: 119).  Where No Vultures Fly has been described as ‘King Solomon’s Mines nationalised by Sir Michael Balcon’ (quoted in Spicer, 2003: 70). West of Zanzibar features a similar ethos and wears its politics on its sleeve, sometimes coming across as strident and didactic in its underscoring of the ‘harmful’ influence of the Arabic traders and the paternal devotion of Steel’s white British game ranger. In the opening sequence, as we are shown dhows plowing through the waves, Payton narrates, telling us, ‘For a thousand years, the dhows of Arabia have come sailing to the shores of Africa, West of Zanzibar. With the winds of the monsoon behind them, they bring dates and carpets, salt and sandalwood, returning with the treasures of Africa to the bazaars of the East. [….] Not so very long ago, these vessels traded in slaves, the black gold of Africa, primitive tribesmen torn from their homes to serve in the palaces and harems of Arabia. A few of these dhows cling to their ancient ways, but the trade is no longer in slaves. Now it is ivory, the white gold of Africa, that draws them to the secret creeks of the mainland [….] Their influence is often disastrous’. Later, Payton confronts the leader of the Kenyan tribe, Ushingo (Edric Connor), when he discovers some of the tribesmen have become embroiled in the illegal trade in ivory. Ushingo tells Payton, ’You are my friend. I know they are hunting the elephant for ivory. There is a trouble among my people, like the sickness you express, even to my own son[…] They will not listen to me. They listen only to strangers [who] come from the coastline’ and demand ivory. He adds, ‘It is always the African who is blamed. If an African steals, we are all thieves; if an African kills, we are all murderers’: Ushingo labels the Arab traders as ‘tempters’. Later, he lectures Payton on concepts of justice: ‘The white man’s justice is a strange thing […] It seems to be very kind towards evil men [….] And when the law comes to punish my foolish young men for ivory hunting, will that be one of those legal things too?’ Finally, at the end of the film Payton tells his wife Mary (Sheila Sim – in a role played by Dinah Sheridan in the previous film), ‘There are only two things we need’. ‘What’s that?’, Mary asks. ‘Patience and tolerance’, Payton informs her. Where No Vultures Fly has been described as ‘King Solomon’s Mines nationalised by Sir Michael Balcon’ (quoted in Spicer, 2003: 70). West of Zanzibar features a similar ethos and wears its politics on its sleeve, sometimes coming across as strident and didactic in its underscoring of the ‘harmful’ influence of the Arabic traders and the paternal devotion of Steel’s white British game ranger. In the opening sequence, as we are shown dhows plowing through the waves, Payton narrates, telling us, ‘For a thousand years, the dhows of Arabia have come sailing to the shores of Africa, West of Zanzibar. With the winds of the monsoon behind them, they bring dates and carpets, salt and sandalwood, returning with the treasures of Africa to the bazaars of the East. [….] Not so very long ago, these vessels traded in slaves, the black gold of Africa, primitive tribesmen torn from their homes to serve in the palaces and harems of Arabia. A few of these dhows cling to their ancient ways, but the trade is no longer in slaves. Now it is ivory, the white gold of Africa, that draws them to the secret creeks of the mainland [….] Their influence is often disastrous’. Later, Payton confronts the leader of the Kenyan tribe, Ushingo (Edric Connor), when he discovers some of the tribesmen have become embroiled in the illegal trade in ivory. Ushingo tells Payton, ’You are my friend. I know they are hunting the elephant for ivory. There is a trouble among my people, like the sickness you express, even to my own son[…] They will not listen to me. They listen only to strangers [who] come from the coastline’ and demand ivory. He adds, ‘It is always the African who is blamed. If an African steals, we are all thieves; if an African kills, we are all murderers’: Ushingo labels the Arab traders as ‘tempters’. Later, he lectures Payton on concepts of justice: ‘The white man’s justice is a strange thing […] It seems to be very kind towards evil men [….] And when the law comes to punish my foolish young men for ivory hunting, will that be one of those legal things too?’ Finally, at the end of the film Payton tells his wife Mary (Sheila Sim – in a role played by Dinah Sheridan in the previous film), ‘There are only two things we need’. ‘What’s that?’, Mary asks. ‘Patience and tolerance’, Payton informs her.

The slightly didactic screenplay is enlivened by a number of exciting set pieces. A sequence in which ivory hunters attack and pursue a group of elephants, causing the herd to stampede, intercuts documentary footage with new material and works very nicely. In another sequence, Payton is attacked by a cheetah whilst he hides in a tree spying on the ivory hunters. This leads to his disappearance, and when Mary – with the aid of the tribesmen – searches for him, she discovers a group of buzzards circling a corpse, feeding on it. Mary runs towards the grisly scene, the birds fly away, and she turns away in horror. This, again, is a very effective sequence. A later, equally exciting action set piece, focuses on two men who are chased by an alligator as their canoe capsizes and they are left stranded in the water.  However, West of Zanzibar is ultimately a clunky, and slightly patronising, jungle adventure: Andrew Spicer has stated that ‘Steel could not rescue a strained mixture of travelogue, wildlife documentary, jungle adventure and homily to racial harmony’ (op cit.: 70). However, West of Zanzibar is ultimately a clunky, and slightly patronising, jungle adventure: Andrew Spicer has stated that ‘Steel could not rescue a strained mixture of travelogue, wildlife documentary, jungle adventure and homily to racial harmony’ (op cit.: 70).

The film runs for 92:49 mins (PAL). This running time includes the film’s trailer, which plays immediately after the credits. The film has been released as part of Network’s Ealing Studio Rarities Collection, Volume 1. The contents of this set are as follows: DISC ONE: Escape! (Basil Dean, 1930) (68:20) West of Zanzibar (Harry Watt, 1954) (92:49) DISC TWO: Penny Paradise (Carol Reed, 1938) (69:23) Cheer Up! (Leo Mittler, 1936) (68:43) Gallery (2:31)

Video

Shot in Technicolor, West of Zanzibar looks passable on this DVD release. There is some wear and tear here and there, and colours are faded throughout, but the presentation is perfectly watchable. Judging by the shift in quality, and as to be expected of the period, Paul Beeson’s wildlife footage appears to have been shot on smaller gauge (probably 16mm) film stock than the main feature. The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.33:1, which most likely was its intended aspect ratio.

Audio

Audio is presented by a two-channel mono track which, like the video presentation, shows some wear and tear but is always audible. Sadly, no subtitles are included.

Extras

Overall

West of Zanzibar is a mildly entertaining film, although on a narrative level it is quite clunky and thematically it is a little too didactic. Its representation of naïve Kenyan tribesman, exploitative Arabic traders and paternalistic British game wardens is more than a little outdated, but Steel plays his role well and there are some exciting set pieces. Nevertheless, West of Zanzibar is by far the lesser of Watt’s two African films. The presentation on this disc is serviceable but not brilliant. References: Barr, Charles, 1998: Ealing Studios: A Movie Book. University of California Press Chapman, James, 2005: Past and Present: National Identity and the British Historical Film. London: I B Tauris Relph, Michael: ‘Inside Ealing’. In: Burton, Alan & O’Sullivan, Tim, 2009: The Cinema of Basil Dearden and Michael Relph. Edinburgh University Press Richards, Jeffrey, 1973: Visions of Yesterday. London: Routledge Shaw, Tony, 2006: British Cinema and the Cold War: The State, Propaganda and Consensus. London: I B Tauris Spicer, Andrew, 2003: Typical Men: The Representation of Masculinity in Popular British Cinema. London: I B Tauris This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|