|

|

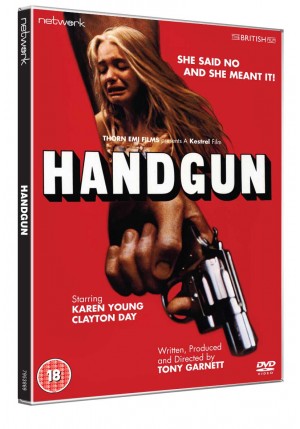

Handgun AKA Deep in the Heart

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th May 2013). |

|

The Film

Handgun (Tony Garnett, 1984)  Tony Garnett began his career in film and television as an actor, he soon moved behind the camera, working as a story editor and producing Ken Loach’s groundbreaking social realist drama ‘Cathy Come Home’ (1966), as part of the BBC’s Wednesday Play strand (1964-70). For the most part, Garnett’s work as a producer is closely allied with the social realist trend: K J Shepherdson asserts that Garnett’s ‘body of work, despite divergence in aesthetic construction, presents a realist and polemical stance maintained over four decades’ (2001: 109). Tony Garnett began his career in film and television as an actor, he soon moved behind the camera, working as a story editor and producing Ken Loach’s groundbreaking social realist drama ‘Cathy Come Home’ (1966), as part of the BBC’s Wednesday Play strand (1964-70). For the most part, Garnett’s work as a producer is closely allied with the social realist trend: K J Shepherdson asserts that Garnett’s ‘body of work, despite divergence in aesthetic construction, presents a realist and polemical stance maintained over four decades’ (2001: 109).

The two feature films Garnett directed, Prostitute (1980) and Handgun, continue this naturalistic, issue-led approach. As Shepherdson notes, Prostitute ‘demonstrated his [Garnett’s] belief in the need to unmask and challenge accepted wisdom, this time confronting assumptions about the role of the prostitute’ (op cit.: 110). The film challenges ‘[e]xpectations of representation’ through its depiction of ‘the women’s behaviour […] as [not] deviant, but as uncomfortably conformist’ through Garnett’s consideration of ‘the nature of our universal “prostitution” under capitalism’ (ibid.). The film is shot in a semi-documentary style, making use of long takes and naturalistic sound editing. Handgun belongs to an era of Garnett’s career in which he elected to work in the US. Garnett apparently struggled to get Handgun into production, and only managed to do so with the support of ‘EMI, a British company who already knew me and who let me do it because it only cost them $2 million’ (Garnett, quoted in Dickenson, op cit.: 26). In the film, Garnett casts an observant eye on the gun culture of the US – specifically Texas – and its relationship with the frontier myth. In Hollywood's New Radicalism: War, Globalisation and the Movies from Reagan to George W. Bush (2006), Ben Dickenson describes Handgun as a ‘tragic exploration of the consequences of a culture in which guns are presented as the solution to social problems’ (26). Shepherdson suggests that in its exploration of these themes, Handgun sometimes ‘slips into an overly didactic exploration of the dangers of “gun culture”’ (op cit.: 110). In the film, quiet history teacher Kathleen Sullivan (Karen Young) relocates to Texas and becomes involved with lawyer and gun collector Larry Keeler (Clayton Day). Their relationship seems to develop nicely, although Kathleen holds herself back from becoming too involved with Larry and refuses to sleep with him. Larry rapes Kathleen, precipitating a profound change in her character: advised that it will be almost impossible to successfully prosecute Larry for the crime, Kathleen cuts her hair and begins to dress in more masculine clothing, and she also begins to spend time on a gun range, learning how to shoot. After buying a Colt Python, Kathleen seeks justice outside the law…  The film opens with sweet music (from the film’s excellent score by Mike Post) over a shot of a school bus travelling through Dallas. However, as the opening titles continue the music segues into a minor key, underscoring the way in which, as the film’s narrative progresses, Kathleen’s romantic ideals will become undercut by her association with Larry. This is a theme that is also highlighted by the school musical that Kathleen, as a pianist, is helping to stage: Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. In the sequence that immediately follows the opening titles, the staging of the school play is introduced. Garnett returns to these rehearsals later in the film, cross-cutting between them and scenes depicting Kathleen’s relationship with Larry. The editing here offers ironic commentary on both Kathleen’s romantic ideals and, more generally, the pressures on women to enter into romantic relationships (in the opening sequence, Kathleen is told by another female character, ‘You need a man’). The film opens with sweet music (from the film’s excellent score by Mike Post) over a shot of a school bus travelling through Dallas. However, as the opening titles continue the music segues into a minor key, underscoring the way in which, as the film’s narrative progresses, Kathleen’s romantic ideals will become undercut by her association with Larry. This is a theme that is also highlighted by the school musical that Kathleen, as a pianist, is helping to stage: Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. In the sequence that immediately follows the opening titles, the staging of the school play is introduced. Garnett returns to these rehearsals later in the film, cross-cutting between them and scenes depicting Kathleen’s relationship with Larry. The editing here offers ironic commentary on both Kathleen’s romantic ideals and, more generally, the pressures on women to enter into romantic relationships (in the opening sequence, Kathleen is told by another female character, ‘You need a man’).

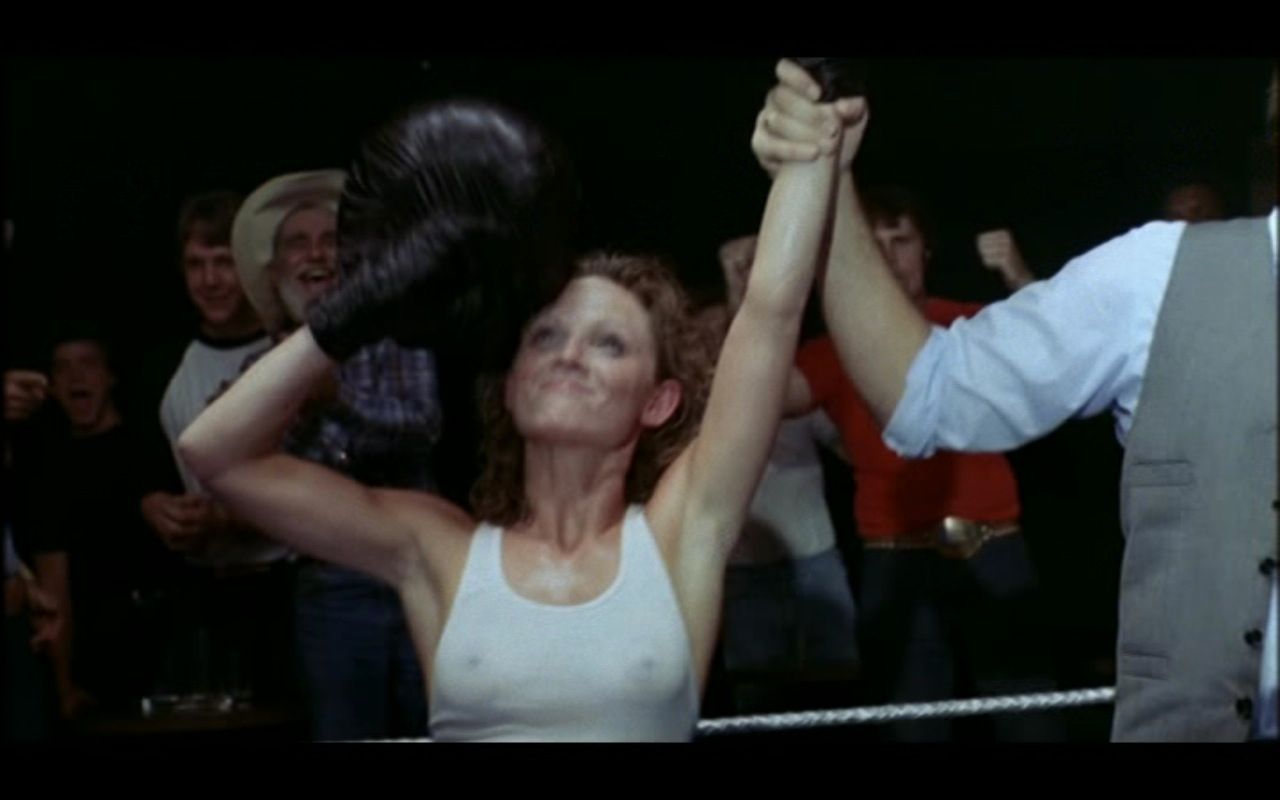

During the rehearsal that opens the film, a male member of staff berates a female teacher who has volunteered to play the piano for the students. From this introductory sequence, we are introduced to the macho culture that, Garnett’s film suggests, pervades Texas and which allows men to publicly ridicule women, assault them in private and ogle them voyeuristically” in a later sequence, Larry will be shown watching the school cheerleaders, a telephoto lens providing close-ups of their upper thighs and red knickers whilst cutaways to Larry demonstrate that we are watching the display from his point of view. Later, just before Larry assaults Kathleen, he – along with his friend and colleague Chuck – is depicted visiting ‘Foxy Boxing’, a female boxing event. The men in the audience whoop and cheer as the women, wearing tight T-shirts through which it can clearly be seen that they are braless, fight in the ring. The positioning of this sequence just prior to the sequence in which Larry rapes Kathleen highlights Garnett’s critique of the culture of machismo, in which such sexualised displays of violence are acceptable, that contributes to Larry’s perception of women, in turn legitimising (for him) his treatment of Kathleen.  Prior to his assault on Kathleen, Larry discusses her with his friend and colleague Chuck (Ben Jones), telling Chuck that he hasn’t slept with Kathleen yet and asserting dryly, ‘You know me, Chuck: always a gentleman. Give a lady a little time and she’ll blossom and flower’. Even after raping Kathleen, Larry does not comprehend that he has committed an immoral act. In the build-up to the crime, Larry holds Kathleen at gunpoint and tells her, ‘You’re a very fortunate young lady, because you are removed from any responsibility whatsoever’. As he forces her to undress, he asserts, ‘Nothing you can do about it. I just want to make love to you. It’s nothing terrible’. The prelude to the attack is filmed in a naturalistic way, which makes it all the more disturbing, and thankfully Garnett cuts away from the rape itself. In the aftermath, Larry shows no remorse at all, displacing the blame onto Kathleen, the victim: ‘I’m really sorry things got a little out of hand back there’, he says insincerely, ‘but it’s partly your own fault, you know, for being so irresistible’. Shortly after, he tries to convince Kathleen that she is the one with a problem: ‘You know, you should at least consider the possibility of getting professional help’, he tells her: ‘You’re so repressed sexually [….] It’s clearly something in your psyche that’s just slightly maladjusted’. Prior to his assault on Kathleen, Larry discusses her with his friend and colleague Chuck (Ben Jones), telling Chuck that he hasn’t slept with Kathleen yet and asserting dryly, ‘You know me, Chuck: always a gentleman. Give a lady a little time and she’ll blossom and flower’. Even after raping Kathleen, Larry does not comprehend that he has committed an immoral act. In the build-up to the crime, Larry holds Kathleen at gunpoint and tells her, ‘You’re a very fortunate young lady, because you are removed from any responsibility whatsoever’. As he forces her to undress, he asserts, ‘Nothing you can do about it. I just want to make love to you. It’s nothing terrible’. The prelude to the attack is filmed in a naturalistic way, which makes it all the more disturbing, and thankfully Garnett cuts away from the rape itself. In the aftermath, Larry shows no remorse at all, displacing the blame onto Kathleen, the victim: ‘I’m really sorry things got a little out of hand back there’, he says insincerely, ‘but it’s partly your own fault, you know, for being so irresistible’. Shortly after, he tries to convince Kathleen that she is the one with a problem: ‘You know, you should at least consider the possibility of getting professional help’, he tells her: ‘You’re so repressed sexually [….] It’s clearly something in your psyche that’s just slightly maladjusted’.

When Kathleen seeks help after her rape, she finds herself the victim of a system that is unsympathetic towards her and offers her little help of achieving a sense of justice. After reporting the crime, Kathleen is described as ‘walking evidence’ and is directed to the hospital for a rape kit. Garnett depicts the trauma of the hospital procedure in documentary-like detail. Later, she seeks solace in the church but is told by the priest that she must ‘forgive’ Larry or she may ‘destroy yourself, your soul, if you’re not careful’. When she tells the priest that she wants to see Larry punished, he tells her ‘it’s not our role to punish’ before, like Larry, passing blame onto the victim: he asks her, ‘Wasn’t there something attractive about the man?’ When she finally speaks to a lawyer about the case, she is told that ‘There’s no real evidence. All we have is your word and the fact that intercourse did take place [....] This guy is a professional, respectable man with no criminal record [….] Before you’d finished [in court], they’d be calling you a whore. Are you ready for that?’ Finding no solace within the law, Kathleen decides to arm herself. Learning to shoot, she opts to buy her own gun. Her instructor, a veteran of the war in Vietnam, takes her to a gun shop where Kathleen’s culture shock (she is from Boston, originally) is communicated visually and aurally: parodic ‘good ol’ boy’ music (a cover version of ‘God, Guts and Guns’) plays on the soundtrack as the camera pans over the racks of guns on the walls and in cabinets – shotguns, rifles, revolvers, semi-automatic pistols. The salesman recommends Kathleen buy a Colt Python with a rubber grip (for $485), and Kathleen asks in amazement, ‘I can just come in here and buy this?’ The salesman tells her, ‘Down here, as long as you live in the state, you can buy a weapon, no problem’. When Kathleen meets Larry, she freely admits that the gun culture of Texas is alien to her: ‘I don’t know anything about guns’, she declares. Larry tells her of the 1873 Colt .45, which acquired the nickname ‘The Equalizer’ owing to the ease of its operation, essentially making all men equal in a gunfight. The gun, as Larry informs Kathleen, also acquired the secondary nickname ‘The Peacemaker’ through its association with lawmen. (Larry’s praise for this specific gun is ironic, given his abuse of Kathleen and her ensuing quest for vengeance against him.) Larry informs Kathleen that ‘You can’t possibly understand history down here unless you know something about the Colt revolvers’, underscoring the significance of the revolver for the culture and history of the state: later, Larry will take Kathleen to the Texas State Fair, where she will see a man dressed in full cowboy regalia demonstrating gun play. This sequence foregrounds the association of the history of the southern states, violence and male peacockism. (Prior to the rape of Kathleen, Larry is shown in his bedroom, rubbing lotion on his naked body as he stands in front of a mirror; Garnett cross-cuts this display of male vanity with a scene depicting Kathleen at Mass.) ‘It’s always been the case that the guy who has the best weapon changed the course of history’, Larry adds. Later, Kathleen invites Larry to talk about guns with her class of students, and he informs them of some of the technicalities of gunfights: the necessity of a short barrel for an efficient quickdraw and the relationship between accuracy and the length of a gun’s barrel.  Garnett also explores how this culture of violence has been legitimised through media representations and role models. When Larry picks up Kathleen one evening, they talk about their favourite film stars. ‘That’s easy’, Larry asserts: ‘John Wayne [….] At least he was a real man, unlike the faggots you see these days’. Meanwhile, Kathleen goes with a very different film actor of the same era: Alan Ladd in Shane. ‘He looked so sad and lonely’, she says: ‘such nice eyes’. (At the climax of the film, Kathleen mocks Larry’s praise for Wayne: after shooting him, she taunts him, ‘A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do, eh? […] Who you gonna be, John Wayne? Be Jack Palance [in Shane] […] I always liked him’.) Larry’s praise for Wayne is unsurprising in light of Larry’s investment in the frontier myth. ‘I’ll tell you what’s so special about Texas’, he informs Kathleeen: ‘This is still a frontier. And what I mean by that is, on the frontier in the olden days of the West, on a day to day basis people had to draw in their courage […] and inner resources in order to just exist [...] just live’. His reference to the ethos of individualism and self-reliance that underpin the frontier myth justifies his criticism of social welfare: Larry asserts that welfare programmes are ‘just wrong. I think it’s contrary to the frontier spirit’. ‘You sound just like my father’, Kathleen responds: ‘He’s an anachronism […] He’s very strict with his girls’. ‘I would have been too’, Larry tells her ominously. Garnett also explores how this culture of violence has been legitimised through media representations and role models. When Larry picks up Kathleen one evening, they talk about their favourite film stars. ‘That’s easy’, Larry asserts: ‘John Wayne [….] At least he was a real man, unlike the faggots you see these days’. Meanwhile, Kathleen goes with a very different film actor of the same era: Alan Ladd in Shane. ‘He looked so sad and lonely’, she says: ‘such nice eyes’. (At the climax of the film, Kathleen mocks Larry’s praise for Wayne: after shooting him, she taunts him, ‘A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do, eh? […] Who you gonna be, John Wayne? Be Jack Palance [in Shane] […] I always liked him’.) Larry’s praise for Wayne is unsurprising in light of Larry’s investment in the frontier myth. ‘I’ll tell you what’s so special about Texas’, he informs Kathleeen: ‘This is still a frontier. And what I mean by that is, on the frontier in the olden days of the West, on a day to day basis people had to draw in their courage […] and inner resources in order to just exist [...] just live’. His reference to the ethos of individualism and self-reliance that underpin the frontier myth justifies his criticism of social welfare: Larry asserts that welfare programmes are ‘just wrong. I think it’s contrary to the frontier spirit’. ‘You sound just like my father’, Kathleen responds: ‘He’s an anachronism […] He’s very strict with his girls’. ‘I would have been too’, Larry tells her ominously.

Stephen Lacey suggests that Handgun ‘draws on two kinds of familiar Hollywood story’: the familiar ‘woman-as-victim of a predatory male’ narrative; and the ‘story of a protagonist who is wronged, but can find no redress through the processes of the law, and enacts a revenge of her own’ (2007: 118). These themes had collided before in, for example, Burt Kennedy’s Hannie Caulder (1971) ; but Lacey argues that in marrying these two types of narrative, Handgun ‘challenged the ideological underpinnings of each’ (ibid.). Handgun is not unique amongst revenge films in its focus on a female victim who turns vigilante: Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on Your Grave (1978), Hannie Caulder, Abel Ferrara’s Ms. 45/Angel of Vengeance and Michael Winner’s Dirty Weekend (1993) all feature female victims of a sexual assault who seek violent revenge against their attackers, and this particular subgenre has been alternately criticised as exploiting women and praised as containing crypto-feminist ideas (see Heller-Nicholas, 2011). In Handgun, the representation of Kathleen as a character who is willing to seek revenge underscores that she is ‘in no sense […] a passive victim’ and, as Lacey argues, there is a subtle ‘feminist logic’ within the film that is mitigated somewhat by ‘the fact that in order to become “active” she becomes more “male” than the men around her, donning masculine clothes and learning to shoot’ (Lacey, op cit: 118). Nevertheless, ‘there is a clear but understated sense of the consciously performative about this: her hair-cut and dress in the days after the rape are exaggerated, deliberately denying her femininity as an act of self-protection’ (ibid.).  As Lacey suggests, within the film ‘rape is not an abnormal act committed by a disturbed outsider, but a logical outcome […] of a particular value system’ (op cit.: 118). Larry allows the myths of the Old West to dictate his behaviour, the ‘ethics of gun culture are directly connected to a wider politics’: Larry ‘sneers at blacks, who are all “on welfare”, and espouses self-reliance and “frontier values”’ and Garnett depicts in detail an encounter between Kathleen and another ‘gun nut’, a survivalist who warns Kathleen of an impending race war (ibid.: 118-9). When Kathleen visits the gun range and learns to shoot, ‘[t]he values that saturate gun culture are laid bare’: this is the sequence that ‘several reviewers thought almost like a documentary’ (ibid.: 118). The film as a whole is shot with ‘an observational style familiar to viewers of Garnett’s other films’ and uses ‘long takes to particular effect’ (ibid.: 119). However, this naturalistic aesthetic is mitigated slightly by the use of a non-diegetic score, something absent from Garnett’s earlier productions. Garnett refuses to depict the rape but represents ‘the build up to it […] in a detail that is harrowing and refuses to exploit any potential for eroticism’ (ibid.). As Lacey suggests, within the film ‘rape is not an abnormal act committed by a disturbed outsider, but a logical outcome […] of a particular value system’ (op cit.: 118). Larry allows the myths of the Old West to dictate his behaviour, the ‘ethics of gun culture are directly connected to a wider politics’: Larry ‘sneers at blacks, who are all “on welfare”, and espouses self-reliance and “frontier values”’ and Garnett depicts in detail an encounter between Kathleen and another ‘gun nut’, a survivalist who warns Kathleen of an impending race war (ibid.: 118-9). When Kathleen visits the gun range and learns to shoot, ‘[t]he values that saturate gun culture are laid bare’: this is the sequence that ‘several reviewers thought almost like a documentary’ (ibid.: 118). The film as a whole is shot with ‘an observational style familiar to viewers of Garnett’s other films’ and uses ‘long takes to particular effect’ (ibid.: 119). However, this naturalistic aesthetic is mitigated slightly by the use of a non-diegetic score, something absent from Garnett’s earlier productions. Garnett refuses to depict the rape but represents ‘the build up to it […] in a detail that is harrowing and refuses to exploit any potential for eroticism’ (ibid.).

The film runs for 95:37 mins (PAL) and is uncut.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, with anamorphic enhancement. It’s a strong transfer, with solid colours, good contrast levels and a pleasingly organic, filmlike appearance.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track. This is clear throughout, representing the naturalistic sound design well. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc contains an archival interview with Tony Garnett (6:26), the film’s trailer (2:08) and a gallery (3:58) of posters, lobby cards and on-set stills. The disc also contains the film’s original pressbook as a PDF file.

Overall

An excellent little film, Handgun has, aside from a few television airings, been quite difficult to see for some time. It’s not unique in its focus on a female vigilante, but the film offers an interesting outsider’s perspective on the gun culture of Texas. Garnett takes a quasi-documentary approach to his subject matter, as in his other film as director, Prostitute. This release from Network is more than welcome. The presentation of the film is very strong, and the archival interview with Garnett works to contextualise the film. This release of this underrated, fascinating film is highly recommended. References: Dickenson, Ben, 2006: Hollywood's New Radicalism: War, Globalisation and the Movies from Reagan to George W. Bush. London: I B Tauris Heller-Nicholas, Alexandra, 2011: Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study Lacey, Stephen, 2007: Tony Garnett. Manchester University Press Shepherdson, K J, 2001: ‘Tony Garnett’. In: Allon, Yoram et al (eds), 2001: Contemporary British and Irish Film Directors: A Wallflower Critical Guide. Manchester: Wallflower Press: 109-10 This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|