|

|

Night Train AKA Pociag

R0 - United Kingdom - Second Run Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st June 2013). |

|

The Film

Night Train (Pociag/Baltic Express) (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1959) Night Train (Pociag/Baltic Express) (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1959)

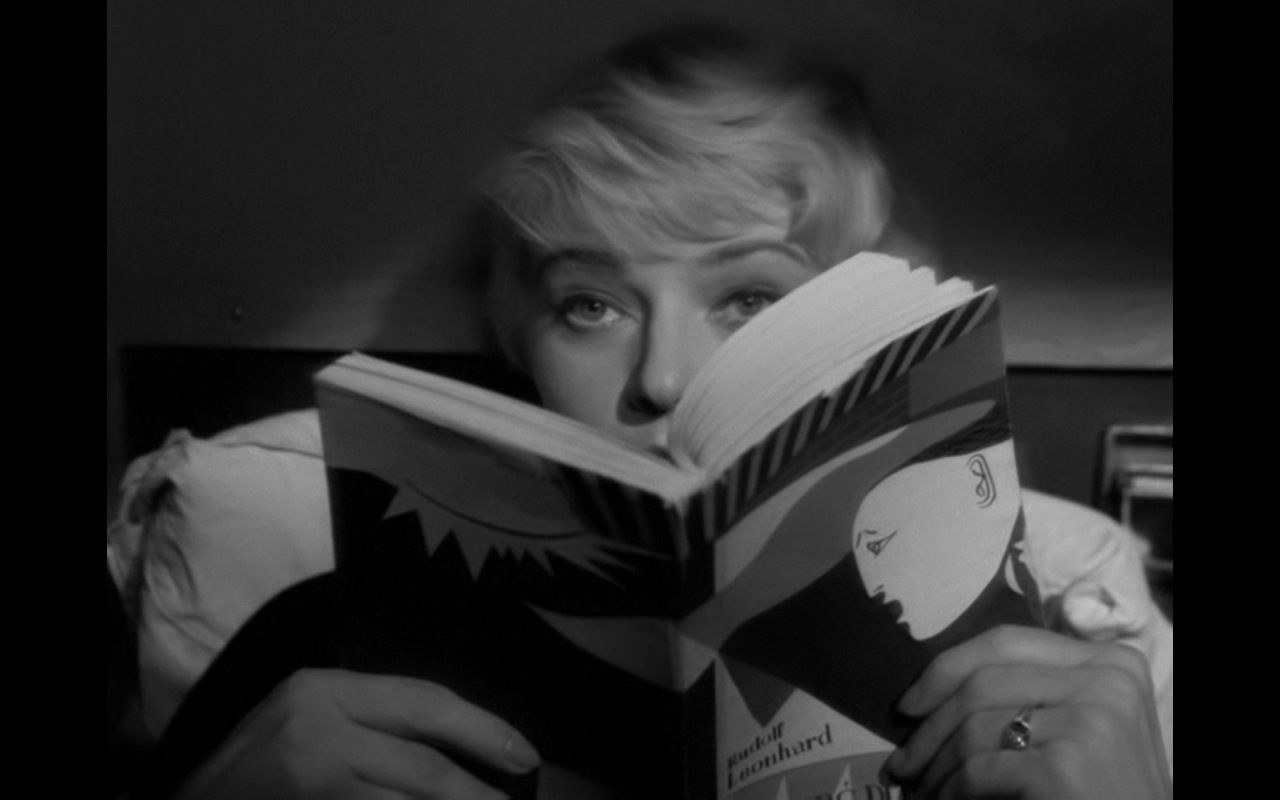

The Polish film director Jerzy Kawalerowicz, a former art student, ‘entered postwar life burdened with the problems of his entire generation, having grown to maturity during the war, and being closely acquainted with the reality of the country from within’ (Liehm & Liehm, 1977: 118). Kawalerowicz’s cinema is one that is dominated by a theme of disillusionment: ‘the disillusionment of the resistance movement, the distaste for traditional Polish romanticism, the desire to maintain artistic independence, and the simultaneous fear of losing contact with the people’ (ibid.). His first film (The Village Mill/Gromada) had been made only seven years prior to Night Train, in 1952. András Bálint Kovács points out that whilst Night Train was praised by many Western critics, in Poland the film received bad reviews, and Kovács suggests this was because the film broke ‘with the dilemma between romantic heroism and everyday realism’ that dominated Polish cinema at during the 1950s (2007: 286). The narrative of Night Train is deceptively simple. A group of passengers boards a train that is bound for the Baltic seaside resort of Gdynia, traveling via Starogard. A mysterious man wearing sunglasses, Jerzy (Leon Niemczyk), is forced against his wishes to share a compartment on a sleeper carriage with a woman, Marta (Lucyna Winnicka). Marta is being pursued by Staszek (Zbigniew Cybulski), a young man with whom Marta has recently ended a brief affair. Meanwhile, the other passengers on the train read a story in the newspaper about a murder and begin to suspect the aloof and mysterious Jerzy of being a killer-on-the-run. However, Jerzy, who is in fact a surgeon fleeing the city after one of his patients died on his operating table, leads the police to the real murderer; the train continues its journey.  Night Train is ‘a film with Hitchcockian overtones’ that, Mirek Haltof argues, ‘defies simple interpretations’ (2002: 99). Although superficially, Night Train may be considered a noir-ish thriller along the lines of Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1956), in which the innocent musician Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda) is mistaken for a criminal, the film’s resolution highlights the extent to which the pursuit of the murderer is really little more than a subplot: after the real killer has been captured, the train continues on its journey. Marta manages to convince Staszek that she does not want to rekindle their relationship, and shows an interest in Jerzy. However, Jerzy does not reciprocate, and the characters leave the train as they entered it: isolated and alone. Kawalerowicz finishes the film with a dolly shot of the empty carriages: at this point, the train seems as much a character within the film as Marta and Jerzy, a blank witness to the alienation that we have encountered amongst its passengers. Night Train is ‘a film with Hitchcockian overtones’ that, Mirek Haltof argues, ‘defies simple interpretations’ (2002: 99). Although superficially, Night Train may be considered a noir-ish thriller along the lines of Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1956), in which the innocent musician Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda) is mistaken for a criminal, the film’s resolution highlights the extent to which the pursuit of the murderer is really little more than a subplot: after the real killer has been captured, the train continues on its journey. Marta manages to convince Staszek that she does not want to rekindle their relationship, and shows an interest in Jerzy. However, Jerzy does not reciprocate, and the characters leave the train as they entered it: isolated and alone. Kawalerowicz finishes the film with a dolly shot of the empty carriages: at this point, the train seems as much a character within the film as Marta and Jerzy, a blank witness to the alienation that we have encountered amongst its passengers.

For Haltof, the characters’ psychology is ‘barely sketche[d] […] yet the characters are intriguing and the story involving, almost suspenseful’ (ibid.). As András Bálint Kovács notes, part of this suspense is due to the fact that the film’s narrative takes place in a ‘closed experimental situation [the confines of the train] in which the characters’ [Jerzy and Marta] relationship is constructed upon their actual and immediate interactions rather than on their background. All we know about them are some details of their immediate present life, which in both cases represent a break with the past’ (2007: 287).  Through the photography, Kawalerowicz and cinematographer Jan Laskowski provide us with an objective depiction of the characters and narrative: the film begins with the credits playing over an overhead shot of crowds of people within the train station, all of them moving in different directions and at different speeds. The shot seems like a visual metaphor for the impossibility of any meaningful, lasting connection between the characters: their relationships are transitory. (This depiction of human relationships as fleeting is underscored by the dialogue: at one point, Marta reflects on her brief affair with Staszek, telling Jerzy that she ‘thought of revenge, of killing him’ because the young man ‘is madly ambitious […] always searching for something. He is afraid of anonymity [….] Nobody wants to love. Everybody wants to be loved’.) A similar overhead shot takes place later, as the passengers (who have left the train to pursue the murderer through fields that surround the train line) gather round the killer. On board the train, Kawalerowicz and Laskowski emphasise the confined nature of the sleeper carriages through shooting the passengers in the corridors as they try to pass one another. The carefully-composed photography maintains tension: for the most part, the film takes place on the train, with the photography underscoring the closed-in, claustrophobic nature of the compartments on the sleeper carriage and the corridors outside. In most scenes, ‘[w]hile the background is moving (images behind the train windows), the center of the action remains comparatively motionless’ (Haltoff, op cit.: 99). The ‘expectations and unstated desires’ of the people on the sleeper carriage is thus ‘matched by the rhythm of the moving train, the opening and closing of compartment doors, the overall monotony of the travel’ (ibid.). Through the photography, Kawalerowicz and cinematographer Jan Laskowski provide us with an objective depiction of the characters and narrative: the film begins with the credits playing over an overhead shot of crowds of people within the train station, all of them moving in different directions and at different speeds. The shot seems like a visual metaphor for the impossibility of any meaningful, lasting connection between the characters: their relationships are transitory. (This depiction of human relationships as fleeting is underscored by the dialogue: at one point, Marta reflects on her brief affair with Staszek, telling Jerzy that she ‘thought of revenge, of killing him’ because the young man ‘is madly ambitious […] always searching for something. He is afraid of anonymity [….] Nobody wants to love. Everybody wants to be loved’.) A similar overhead shot takes place later, as the passengers (who have left the train to pursue the murderer through fields that surround the train line) gather round the killer. On board the train, Kawalerowicz and Laskowski emphasise the confined nature of the sleeper carriages through shooting the passengers in the corridors as they try to pass one another. The carefully-composed photography maintains tension: for the most part, the film takes place on the train, with the photography underscoring the closed-in, claustrophobic nature of the compartments on the sleeper carriage and the corridors outside. In most scenes, ‘[w]hile the background is moving (images behind the train windows), the center of the action remains comparatively motionless’ (Haltoff, op cit.: 99). The ‘expectations and unstated desires’ of the people on the sleeper carriage is thus ‘matched by the rhythm of the moving train, the opening and closing of compartment doors, the overall monotony of the travel’ (ibid.).

The film ‘develops slowly’ until the sequence in which the police board the train, looking for the murderer, and the chase that follows ‘interrupts the rhythm of the film, and temporarily moves the action out of the train’ (Haltof, op cit.: 99). It’s an arresting sequence: the man runs through the fields, pursued by the train’s passengers, and unsuccessfully attempts to fend the mob away with a large tree branch. The sequence takes place in near-silence, the soundtrack dominated by a dog barking in the distance. After the mob have leapt upon the man and assaulted him, they stand back, some of them clearly disturbed by their animalistic behaviour – much like the villagers who bray for the execution of the ‘witch’ in the opening sequence of Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968), only to turn away, empty and disgusted, after the woman has been hanged. But this is not the end of the film: as Haltof notes, when the true murderer is captured, this is ‘neither the climax nor the finale of the film. The train continues its unhurried journey and stops at its destination without any major dramatic shift. The trip ends as it began—in normality’ (ibid.).  Aicja Helman has claimed that Night Train introduced a new motif to Kawalerowicz’s work, one that would become important to many of his later films: the character of Marta represents the ‘woman who feels foreign in a world ruled by men, a woman who is not understood, and who attempts to slip away from men’s hates and loves, both of which are painful’ (quoted in Haltof, op cit.: 99). Both Marta and Jerzy are fleeing from something: Kovács describes this as ‘the Antonioni pattern of dramatic disappearance: both characters are at an empty point of their respective lives’, with Marta fleeing from an ex-lover and Jerzy running from the death of his patient on the operating table (op cit.: 287). Both characters ‘find themselves at an empty and indeterminate spot on a train in a randomly created situation, between two specific points, trying to leave something behind. This is a perfectly abstract situation of emptiness where new beginnings are usually possible. But conforming to the pattern of disappearance in the Antonioni films, instead of building up a new system of relationships, the story becomes emptied out entirely. Nothing is left from their encounter, no new relationship is created, and their arrival at their destination, especially for the woman, is akin to a dead end’ (ibid.). The murderer who is sought by the police killed his wife, and for Ewa Mazierska the melancholy jazz score by Andrzej Trzakowski, based on Artie Shaw’s ‘Moon Ray’, ‘underscores the impossibility of love, of its being condemned to failure even before it properly begins’ (2008: 152). Kovács reminds us that at the end of the film, as ‘the train finally arrives at its destination the passengers go their own ways, relations started on the train vanish at once, the woman [Marta] walks alone on the empty seashore, and the film ends showing us the deserted compartments one by one, generating a feeling of disturbing emptiness’ (op cit.: 287). Aicja Helman has claimed that Night Train introduced a new motif to Kawalerowicz’s work, one that would become important to many of his later films: the character of Marta represents the ‘woman who feels foreign in a world ruled by men, a woman who is not understood, and who attempts to slip away from men’s hates and loves, both of which are painful’ (quoted in Haltof, op cit.: 99). Both Marta and Jerzy are fleeing from something: Kovács describes this as ‘the Antonioni pattern of dramatic disappearance: both characters are at an empty point of their respective lives’, with Marta fleeing from an ex-lover and Jerzy running from the death of his patient on the operating table (op cit.: 287). Both characters ‘find themselves at an empty and indeterminate spot on a train in a randomly created situation, between two specific points, trying to leave something behind. This is a perfectly abstract situation of emptiness where new beginnings are usually possible. But conforming to the pattern of disappearance in the Antonioni films, instead of building up a new system of relationships, the story becomes emptied out entirely. Nothing is left from their encounter, no new relationship is created, and their arrival at their destination, especially for the woman, is akin to a dead end’ (ibid.). The murderer who is sought by the police killed his wife, and for Ewa Mazierska the melancholy jazz score by Andrzej Trzakowski, based on Artie Shaw’s ‘Moon Ray’, ‘underscores the impossibility of love, of its being condemned to failure even before it properly begins’ (2008: 152). Kovács reminds us that at the end of the film, as ‘the train finally arrives at its destination the passengers go their own ways, relations started on the train vanish at once, the woman [Marta] walks alone on the empty seashore, and the film ends showing us the deserted compartments one by one, generating a feeling of disturbing emptiness’ (op cit.: 287).

The film looks back to then-recent history. When a priest on the train encounters a man in the corridor and asks if the man is going to lie down in his compartment, he is told, ‘I can’t, father. Those berths one above another are just like bunks, and I spent four years in Buchenwald’. Similarly, Ewa Mazierska suggests that when one of the characters asserts ‘Feelings are no fashionable’, the line of dialogue implies that ‘previously feelings were not in vogue in Poland, which can be read as a clear allusion to the period of Stalinism’ (op cit.: 151). Mazierska suggests this comment is central to the film, which ‘presents a number of characters, each consumed by their own unresolved personal crises and their hunger for feelings’ (ibid.). This is foregrounded by the relationship between Marta and Staszek: for the former, the brief relationship between the pair ‘did not matter much’, but for Staszek it ‘proved very important’ (ibid.). The film is uncut and runs for 93:57 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The monochrome image is very strong, displaying good contrast and tonality. The print is handsome, being based on a new HD restoration of the film that was supervised by Jan Laskowski.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track which is clear and free of issues. Optional English subtitles, apparently based on a new translation of the Polish dialogue, are provided.

Extras

The case includes a handsome sixteen page booklet with a short essay on Night Train and a biography of Kawalerowicz, both written by Michael Brooke. The disc also includes a short featurette, ‘About Night Train’ (6:48), which reflects on the production of the film.

Packaging

The disc is housed in a standard Amaray keepcase.

Overall

Haltof allies Night Train with Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water; both films employ ‘elements of the thriller genre’ and avoid ‘political or social commitment’, defying ‘the communist expectations of a work of art’ (2002: 100). It’s a fascinating little film, a classic within Polish post-war cinema. This presentation from Second Run is excellent; the optional subtitles are clean and error free, and the monochrome image is strong in detail, clarity, contrast and tonality. This release comes with the highest recommendation. Haltof allies Night Train with Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water; both films employ ‘elements of the thriller genre’ and avoid ‘political or social commitment’, defying ‘the communist expectations of a work of art’ (2002: 100). It’s a fascinating little film, a classic within Polish post-war cinema. This presentation from Second Run is excellent; the optional subtitles are clean and error free, and the monochrome image is strong in detail, clarity, contrast and tonality. This release comes with the highest recommendation.

References: Haltof, Mirek, 2002: Polish National Cinema. Oxford: Berghahn Books Kovács, András Bálint, 2007: Screening Modernism: European Art Cinema, 1950-1980. University of Chicago Press Liehm, Mira & Liehm, Antonin J, 1977: The Most Important Art: Eastern European Film After 1945. University of California Press Mazierska, Ewa, 2008: Masculinities in Polish, Czech and Slovak Cinema: Black Peters and Men of Marble. Oxford: Berghahn Books

|

|||||

|