|

|

Abdul the Damned

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th July 2013). |

|

The Film

Abdul the Damned (Karl Grune, 1935)  Produced in 1934, Abdul the Damned offers the story of the 34th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Abdul Hamid II, as a thinly-veiled allegory of Hitler’s regime: the film’s writer Robert Neumann, director Karl Grune, and producer Max Schach were émigrés who had escaped the Nazi regime. In reality, Abdul Hamid II was in part responsible for the modernisation of the Ottoman Empire; in the early years of his reign, his politics were largely liberal, and in his modernisation efforts he found resistance from some of the more conservative camps within Turkish society. However, over time he became something of a tyrant, once asserting that ‘I made a mistake when I wished to imitate my father, Abdulmecit, who sought to reform by persuasion and liberal institutions. I shall follow the footsteps of my grandfather, Sultan Mahmut. Like him, I now understand that it is only by force that one can move the people with whose protection God has entrusted me’ (quoted in Rae, 2002: 139). He increasingly favoured the centralisation of power, and in 1878 he abandoned the country’s constitution to implement ‘a highly centralised, autocratic and personal form of control of the Ottoman Empire’ (ibid.). His regime was disrupted by the 1908 revolution led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), known informally as the ‘Young Turks’, who established the Second Constitutional Era within Turkey. The Young Turks fought for a reinstatement of the 1876 constitution written by Midhat Pasha and a return to a constitutional monarchy. Produced in 1934, Abdul the Damned offers the story of the 34th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Abdul Hamid II, as a thinly-veiled allegory of Hitler’s regime: the film’s writer Robert Neumann, director Karl Grune, and producer Max Schach were émigrés who had escaped the Nazi regime. In reality, Abdul Hamid II was in part responsible for the modernisation of the Ottoman Empire; in the early years of his reign, his politics were largely liberal, and in his modernisation efforts he found resistance from some of the more conservative camps within Turkish society. However, over time he became something of a tyrant, once asserting that ‘I made a mistake when I wished to imitate my father, Abdulmecit, who sought to reform by persuasion and liberal institutions. I shall follow the footsteps of my grandfather, Sultan Mahmut. Like him, I now understand that it is only by force that one can move the people with whose protection God has entrusted me’ (quoted in Rae, 2002: 139). He increasingly favoured the centralisation of power, and in 1878 he abandoned the country’s constitution to implement ‘a highly centralised, autocratic and personal form of control of the Ottoman Empire’ (ibid.). His regime was disrupted by the 1908 revolution led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), known informally as the ‘Young Turks’, who established the Second Constitutional Era within Turkey. The Young Turks fought for a reinstatement of the 1876 constitution written by Midhat Pasha and a return to a constitutional monarchy.

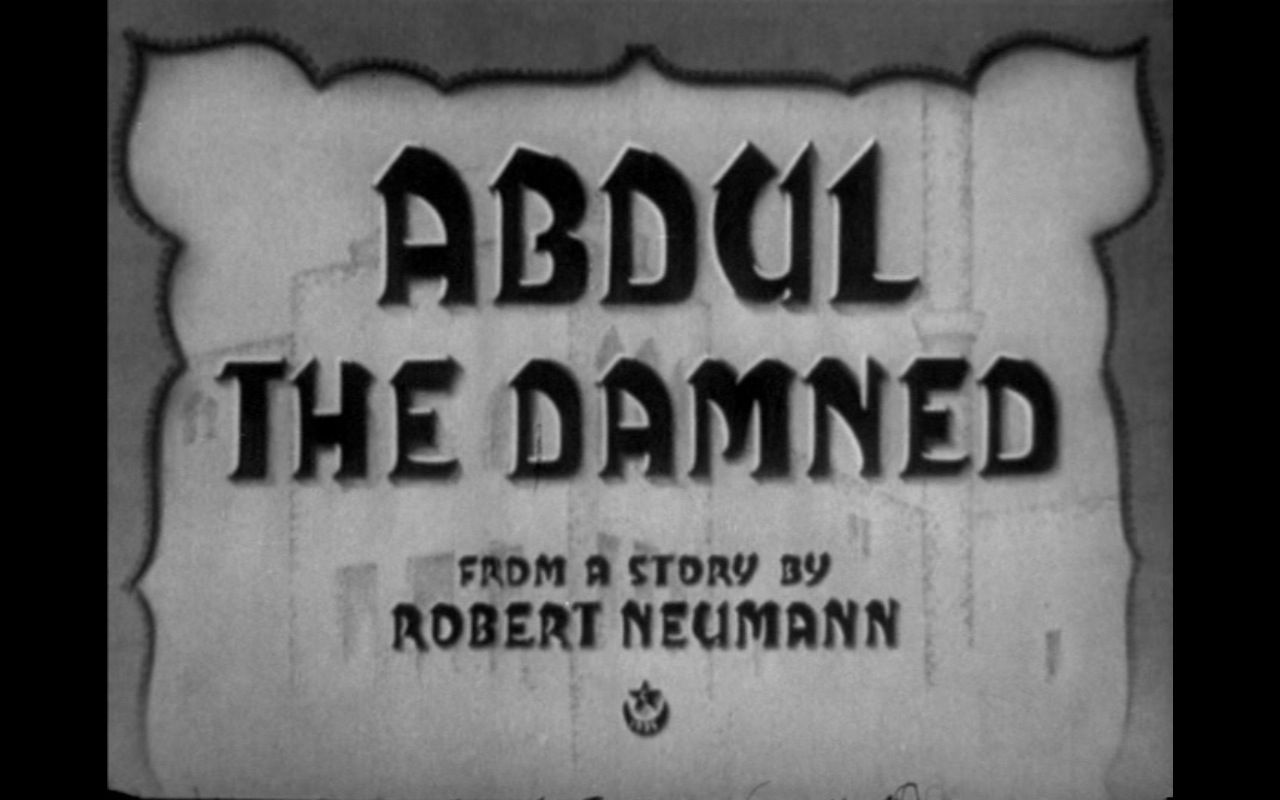

Grune’s film dramatises the build-up to the Young Turk revolution. The film begins with a long title card, which outlines the context of the film’s narrative: the card tells us that, ‘In the Christian year of 1908, the Moslem Empire of Turkey was ruled by Abdul Hamid II…… ABDUL THE DAMNED. Last of the absolute monarchs, his people had lived for years in cruel oppression. At last they have broken into revolt, led by Hilmi Pasha, founder of the Young Turk party, distinguished from the old order by their white fez. Fearing their rising power, the Sultan promised to sign a new constitution guaranteeing liberty and civil rights to all….’  Following this opening title, the film introduces Ali (Esme Percy), the Sultan’s Chief Eunuch, who announces that he will act as the Sultan’s proxy in the signing of the new constitution. After this, we are shown Talak (John Stuart), an officer in the Turkish army, and Therese (Adrienne Ames), a Viennese singer, on a train bound for Constantinople. Dialogue tells us that Talak has been in exile and is returning to Turkey for the first time in five years. Therese’s conversations with the other passengers tell her something about Abdul Hamid II’s (Fritz Kortner) regime: an elderly woman tells Therese that the Sultan is rumoured to have ‘three hundred wives’, and in his palace ‘men die like flies’ whilst the Sultan smiles. ‘Constantinople, a wonderful city, but like everything in Turkey… beautiful, but very, very cruel’, the old woman tells Therese. Meanwhile, Talak observes that he doesn’t ‘think the government will be a government much longer’. Following this opening title, the film introduces Ali (Esme Percy), the Sultan’s Chief Eunuch, who announces that he will act as the Sultan’s proxy in the signing of the new constitution. After this, we are shown Talak (John Stuart), an officer in the Turkish army, and Therese (Adrienne Ames), a Viennese singer, on a train bound for Constantinople. Dialogue tells us that Talak has been in exile and is returning to Turkey for the first time in five years. Therese’s conversations with the other passengers tell her something about Abdul Hamid II’s (Fritz Kortner) regime: an elderly woman tells Therese that the Sultan is rumoured to have ‘three hundred wives’, and in his palace ‘men die like flies’ whilst the Sultan smiles. ‘Constantinople, a wonderful city, but like everything in Turkey… beautiful, but very, very cruel’, the old woman tells Therese. Meanwhile, Talak observes that he doesn’t ‘think the government will be a government much longer’.

After an attempt is made on the Sultan’s life by a Young Turk, injuring his double, Kislar (also played by Kortner), the Sultan orders the young would-be assassin to be interrogated by Kadar (Nils Asther), Abdul Hamid II’s Chief of Police. The young man claims that he was not ordered to assassinate the Sultan: he was acting by himself. Kadar and the Sultan are shown to be complicit in the torturing of the prisoner. ‘I hope you haven’t been torturing the prisoner’, Kadar informs the guards holding the young man, a hint of sarcasm in his voice. ‘No, sir. The new constitution forbids it’, he is told. ‘Quite so. Let’s look to the future and be truly modern’, Kadar says. When the young man is killed, Talak is told that the young man was killed trying to escape. However, he sees through Kadar’s circumvention of the new constitution: ‘Execution after trial, not before’, Talak says.  After Abdul has watched Therese’s performance, he sends an emissary to praise her singing, giving her the gift of jewels. The Sultan, it seems, is infatuated with Therese and wants her to remain ‘under the roof of his palace, as lady of the household’. She declines and is reminded that the Sultan is unaccustomed to not getting what he desires. ‘You forget I’m an Austrian subject, and not a slave girl from one of his provinces’, Therese says. ‘You have a typically Western view of our customs [….] We have a law here against vagabonds and travelling actors [….] Legally, you have no right in Turkey at all. But of course, we are easygoing. People come and go. One young lady more or less is hardly noticed. Her presence is charming. But her absence…’ she is threatened subtly. After Abdul has watched Therese’s performance, he sends an emissary to praise her singing, giving her the gift of jewels. The Sultan, it seems, is infatuated with Therese and wants her to remain ‘under the roof of his palace, as lady of the household’. She declines and is reminded that the Sultan is unaccustomed to not getting what he desires. ‘You forget I’m an Austrian subject, and not a slave girl from one of his provinces’, Therese says. ‘You have a typically Western view of our customs [….] We have a law here against vagabonds and travelling actors [….] Legally, you have no right in Turkey at all. But of course, we are easygoing. People come and go. One young lady more or less is hardly noticed. Her presence is charming. But her absence…’ she is threatened subtly.

Therese is more interested in Talak, to whom she eventually becomes engaged. Talak and Therese make plans to flee to France, where ‘everything is kind and real and secure, not like this country, full of smiles and treachery, where even loveliness is a mask of evil. Let’s go again, out of this nightmare country’. However, Talak, who is aware that the Sultan and Kadar conspired to execute the prisoner behind the failed attempt on the Sultan’s life, is thrown into the palace’s cells, and Therese is blackmailed into wedding the Sultan. As James C Robertson argues, the film ‘slowly turns into a study of paranoia as a mental basis for a political dictatorship’ (1985: 96). In this sense, there are man parallels between Abdul the Damned and more recent allegorical studies of similarly tyrannical regimes: Lee Tamahori’s The Devil’s Double (2011), for example, focuses on Uday Hussein’s similar use of a double (Latif Yahia; both roles are played by Dominic Cooper), and like Abdul the Damned, once the film has established its broad political canvas it becomes an increasingly interior study in paranoia. As Robertson goes on to add, ‘[t]he new constitution of 1908 in Turkey forbids torture, but a prisoner who has tried to assassinate the Sultan is nevertheless tortured to death only to be described later by the Sultan’s government as having been shot while trying to escape’ (ibid.). Robertson notes that the film’s depiction of Abdul Hamid II’s plot, with his police chief Kadar-Pasha (Nils Asther), to assassinate the Old Turk leader Hassan-Bey (Walter Rilla) is ‘a close parallel to the role of Hitler and his SS chief, Heinrich Himmler, in the destruction of the Nazi storm troop force, the SA, and its leader, Ernst Rohm, during the Night of the Long Knives’ in 1934: many of the Young Turks are executed ‘in cold blood but are referred to subsequently in the dialogue as having died while trying to escape, the usual Nazi euphemism for liquidation’ (ibid.: 97).  Although the film is critical of Abdul Hamid II, it is not wholly supportive of the Young Turk movement either: early in the film, Therese observes a group of Young Turks, noting that ‘They seem awfully excited tonight’. To this, Talak – who later becomes associated with the Young Turk revolution – notes, ‘Excited? Drunk. Ideas they don’t even understand. They want to borrow a parliament from England, an army from German and a language from France: everything that isn’t Turkish’. However, against the ideals of the Young Turks, the Sultan’s authority carries an air of snobbish vanity and unpredictability. Criticising Kislar’s performance as his double, the Sultan declares, ‘Well, I suppose a royal bearing cannot be learned: one must be born to it’. (This is an interesting sequence in which the Sultan and Kislar, both played by the same actor, are reflected in a series of mirrors, the doubling of identity within the narrative represented visually by the plethora of reflections of both the Sultan and his ‘copy’.) In another sequence, as Abdul Hamid II enters a room, another character notes that ‘He’ll do what he always does: what we least expect’. Whilst, in public, the Sultan pays lip service to the new constitution, he is shown to be more than willing to resort to despotic methods when pushed: as James Ron has noted, as a general rule of thumb ‘the more securely the state dominates society, the more incentives it faces to reduce its reliance on despotic methods’ (2003: 20). Although the film is critical of Abdul Hamid II, it is not wholly supportive of the Young Turk movement either: early in the film, Therese observes a group of Young Turks, noting that ‘They seem awfully excited tonight’. To this, Talak – who later becomes associated with the Young Turk revolution – notes, ‘Excited? Drunk. Ideas they don’t even understand. They want to borrow a parliament from England, an army from German and a language from France: everything that isn’t Turkish’. However, against the ideals of the Young Turks, the Sultan’s authority carries an air of snobbish vanity and unpredictability. Criticising Kislar’s performance as his double, the Sultan declares, ‘Well, I suppose a royal bearing cannot be learned: one must be born to it’. (This is an interesting sequence in which the Sultan and Kislar, both played by the same actor, are reflected in a series of mirrors, the doubling of identity within the narrative represented visually by the plethora of reflections of both the Sultan and his ‘copy’.) In another sequence, as Abdul Hamid II enters a room, another character notes that ‘He’ll do what he always does: what we least expect’. Whilst, in public, the Sultan pays lip service to the new constitution, he is shown to be more than willing to resort to despotic methods when pushed: as James Ron has noted, as a general rule of thumb ‘the more securely the state dominates society, the more incentives it faces to reduce its reliance on despotic methods’ (2003: 20).

When submitted to the BBFC, the film was viewed by Edward Shortt, the then-president of the organisation, in the presence of staff from the Foreign Office. A decision was made to cut 625 feet (approximately seven minutes) from the picture: Robertson notes that ‘[w]hether this was to avoid possible difficulties in Anglo-German or Anglo-Turkish relations remains unclear, especially as the present National Film Archive print is 127 feet less than the original version’ (ibid.). It’s worth noting that Errol Flynn plays a small role as one of the palace guards. He was spotted by Irving Asher, Warners’ head of production, who tested him before giving him a six month contract (see Morris, 2006: 8). This version of the film is based on the National Film Archive print, thus suffering unknown cuts, and runs for 105:02 mins (PAL). (It’s unlikely that an ‘uncut’ version of the film exists.)

Video

The excellent cinematography, including some astounding trick photography depicting the Sultan and Kislar onscreen together, is by the Czech photographer Otto Kanturek. The excellent cinematography, including some astounding trick photography depicting the Sultan and Kislar onscreen together, is by the Czech photographer Otto Kanturek.

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The print used for this DVD release shows some fairly heavy wear and tear throughout: it’s never less than watchable, but it shows much heavier damage than some of the film’s in Network’s Ealing Studios Rarities collections, for example. There is also some intermittent telecine wobble.

Audio

Audio is presented (in English) via a two-channel mono track. The audio track, like the print, is worn and sometimes dominated by pops and crackles. Nevertheless, dialogue is always audible. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc contains a stills gallery (4:43).

Overall

Abdul the Damned is an interesting, well-shot film that has clear resonance for the era in which it was produced. There are some very clever sequences within the film: for example, at one point Grune cross-cuts between Therese, on the day of her wedding to the Sultan, Ali placing jewellery on her wrists, to the imprisoned Talak being placed in chains in the dungeons of the palace. As the wedding continues, Grune cross-cuts between the wedding and the execution of prisoners that is taking place at the same time; Therese hears the gunshots and defiant singing of the prisoners, causing her to faint. The film’s dialectical representation of the tensions in Turkish society (Kadar, the agent of the sultan’s will, symbolises repression and tyranny; Talak is more enlightened and ‘modern’/Westernised) may seem a little quaint and arguably more than a little reductive. However, the film is dramatically very strong and, ultimately, has some still-relevant points to make about power and despotism. This release is based on a worn print, cut by the BBFC on its first release (and suffering unknown cuts since then) but is never less than watchable. It’s a fascinating, largely forgotten picture. Some more contextual material would be welcomed, but even without it this release is commendable. References: Morris, Oswald, 2006: Huston, We Have a Problem: A Kaleidoscope of Filmmaking Memories. Scarecrow Press Rae, Heather, 2002: State Identities and the Homogenisation of Peoples. Cambridge University Press Robertson, James C, 1985: The British Board of Film Censors: Film Censorship in Britain, 1896-1950. London: Taylor & Francis Ron, James, 2003: Frontiers and Ghettos: State Violence in Serbia and Israel. University of California Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|