|

|

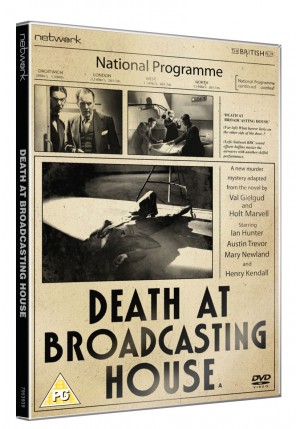

Death at Broadcasting House AKA Death at a Broadcast AKA Death of a Broadcast

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (21st August 2013). |

|

The Film

Death at Broadcasting House AKA Death at a Broadcast (Reginald Denham, 1934)  Finding a belated release in the US in 1941 (with the new title Death at a Broadcast) in order to capitalise on Ian Hunter’s then-new found popularity, Reginald Denham’s 1934 murder mystery Death at Broadcasting House is essentially an Agatha Christie-like whodunit with some strongly humorous elements. Based on the novel of the same title (retitled London Calling for its American publication) written by Val Gielgud and ‘Holt Marvell’ (the pen-name of Eric Maschwitz), it has been suggested that the film’s American release led to elements of its narrative being co-opted by the 1942 Abbott and Costello film Who Done It? (Erie C Kenton). In Who Done It?, Bud and Lou play a hapless duo, with aspirations to write murder mysteries, who find themselves in the middle of a real-life murder at a radio station. Finding a belated release in the US in 1941 (with the new title Death at a Broadcast) in order to capitalise on Ian Hunter’s then-new found popularity, Reginald Denham’s 1934 murder mystery Death at Broadcasting House is essentially an Agatha Christie-like whodunit with some strongly humorous elements. Based on the novel of the same title (retitled London Calling for its American publication) written by Val Gielgud and ‘Holt Marvell’ (the pen-name of Eric Maschwitz), it has been suggested that the film’s American release led to elements of its narrative being co-opted by the 1942 Abbott and Costello film Who Done It? (Erie C Kenton). In Who Done It?, Bud and Lou play a hapless duo, with aspirations to write murder mysteries, who find themselves in the middle of a real-life murder at a radio station.

What is interesting about Death at Broadcasting House, both the novel and the film, is its unique setting: drawing on Gielgud’s experience as the BBC’s Head of Radio Drama, the novel offers an insider’s view of the BBC, and both the film and the book provide some fascinating insight into the methods and technologies involved in the production of radio dramas. Simon Elmes notes the verisimilitude within Death at Broadcasting House’s depiction of the workings of Broadcasting House: ‘[n]ow Death at Broadcasting House is hardly Hitchcock […]; even so, it contains a number of fascinating moments that capture the reality of the process of broadcasting 80 years ago. Studios are live and red transmission lights flicker; casts are nervous. Chorus girls run through their routines in one studio while a play is in a chaotic mess in another’ (2013: 74).  The film focuses on the production of a murder-mystery radio play, ‘Murder Immaculate’, written by Rodney Fleming (Henry Kendall), a West End playwright, and starring the husband and wife team of Leopold and Joan Dryden (Austin Trevor and Lilian Oldland). The story opens with actor Sydney Parsons (Donald Wolfit) gasping for breath as if he is being strangled. Shortly, it is revealed that he is in a radio studio, rehearsing his part for ‘Murder Immaculate’ (a play that is, as was customary at the time, to be broadcast live). Parson’s performance is criticised (‘It sounded like gargling’, the producer tells him); to this, Parsons complains, ‘This broadcasting business is getting as bad as the films’. ‘Can’t you understand that I want the public to think they can see the murderer’s hands throttling the life out of you?’, the producer asks Parsons. The film focuses on the production of a murder-mystery radio play, ‘Murder Immaculate’, written by Rodney Fleming (Henry Kendall), a West End playwright, and starring the husband and wife team of Leopold and Joan Dryden (Austin Trevor and Lilian Oldland). The story opens with actor Sydney Parsons (Donald Wolfit) gasping for breath as if he is being strangled. Shortly, it is revealed that he is in a radio studio, rehearsing his part for ‘Murder Immaculate’ (a play that is, as was customary at the time, to be broadcast live). Parson’s performance is criticised (‘It sounded like gargling’, the producer tells him); to this, Parsons complains, ‘This broadcasting business is getting as bad as the films’. ‘Can’t you understand that I want the public to think they can see the murderer’s hands throttling the life out of you?’, the producer asks Parsons.

Meanwhile, it is shown that the two married stars of the production, Leopold and Joan Dryden, have a somewhat turbulent relationship which carries over into the studio. At one point, Dryden steps outside the studio for ‘some air’. ‘You’re very inconsiderate, Joan’, he complains when Joan questions him why he left the studio. ‘That play gets on my nerves’, Joan grumbles. As the play is being performed, Fleming receives a telephone call. As Parsons is recording his death scene in a separate studio, an unseen assailant attacks him. As Parsons’ attacker strangles him, the producer – who is sitting in the mixing studio – believes Parsons to be simply acting his role.  When Parsons’ body is discovered, the producer observes, ‘To think that we broadcast the murder, and that millions of people must have heard the man actually being strangled’. Detective Inspector Gregory (Ian Hunter) is brought in to investigate the crime; Herbert Evans (a young Jack Hawkins) helps to point Gregory in the right direction regarding the killer’s motive. Along the way, Gregory learns how recordings of radio dramas use multiple studios, the factor which enabled Parsons’ murder to go unnoticed by the rest of the cast and crew; Gregory also finds a key piece of evidence in the form of the recording of the broadcast made using the studio’s Blattnerphone machine, which at the time was a very modern piece of equipment. Listening to the recording of the murder, Gregory identifies a ‘slight tapping sound’. The producer suggests that it is simply ‘surface noise on the steel tape’, but Gregory instead believes it to be ‘a watch, worn either by Parsons or the murderer’. When Parsons’ body is discovered, the producer observes, ‘To think that we broadcast the murder, and that millions of people must have heard the man actually being strangled’. Detective Inspector Gregory (Ian Hunter) is brought in to investigate the crime; Herbert Evans (a young Jack Hawkins) helps to point Gregory in the right direction regarding the killer’s motive. Along the way, Gregory learns how recordings of radio dramas use multiple studios, the factor which enabled Parsons’ murder to go unnoticed by the rest of the cast and crew; Gregory also finds a key piece of evidence in the form of the recording of the broadcast made using the studio’s Blattnerphone machine, which at the time was a very modern piece of equipment. Listening to the recording of the murder, Gregory identifies a ‘slight tapping sound’. The producer suggests that it is simply ‘surface noise on the steel tape’, but Gregory instead believes it to be ‘a watch, worn either by Parsons or the murderer’.

The use of the sound recording to solve the case is somewhat reminiscent Dario Argento’s employment of a similar narrative device in his thrilling all’italiana picture The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1969), in which a recording of a telephone call from the killer is revealed to contain, buried in the background noise, the cry of the titular bird. Like the Blattnerphone recording in Death at Broadcasting House, the audio recording of the killer’s telephone call in The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is the key piece of evidence that allows the protagonist to solve the murder that he accidentally witnessed. It could be argued that Death at Broadcasting House was ahead of its time in incorporating some postmodern elements: through its narrative focusing on a murder committed during the recording of another narrative (a murder mystery, no less), it demystifies drama production, showing the techniques involved in creating drama. As Peter Sallis, who starred as Detective Inspector Spears in the 1996 radio dramatization of the novel, notes in his autobiography, ‘Val Gielgud had done quite a good job on it [the novel] and at the time when he wrote this there was no television, so it must have brought people inside Broadcasting House, when they were listening to it, in a very clever way’ (2008: np). (In fact, in its self-referential elements and its focus on the recording of a radio drama, the film could be likened to Peter Strickland’s recent thriller Berberian Sound Studio (2012).) In the introduction to Media Houses, Staffan Ericcson et al suggest that Death at Broadcasting House is a fantasy ‘about the anxieties of modern life’ (2010: 13). Ericcson suggests that Death at Broadcasting House subtly ‘depart[s] from the rules’ of the traditional whodunit. Ericcson argues that classical detective stories predominantly take place ‘within the private sphere, disrupting order by placing dead bodies in the midst of our family circle’; in contrast, Death at Broadcasting House focuses on a murder ‘at the heart of a mediated center: the studios of Broadcasting House’ (2010: 24). Where traditional detectives in fiction must track ‘past events via material clues and eyewitness accounts from the scene of the crime’, Inspector Spears must solve a case which has millions of witnesses who have heard the crime but not seen it (the viewers who listened to the live broadcast in which Parsons was strangled to death) and must therefore ‘reconstruct the locality and traces of a crime that have registered only in the ether’ (ibid.).  In the novel, Spears recognises that in order to solve Parson’s murder, he must understand how a radio drama is produced. Referencing Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Ericcson connects Death at Broadcasting House with Room 101 in George Orwell’s 1984 (1948): Gielgud and Marvell’s novel depicts ‘the traces of a crime committed in the interior of the modern’ and represents Broadcasting House as ‘not only a marvel of technology, but a scary place to be’ (2010: 43). As Ericsson notes, Orwell’s inspiration for Room 101 was a room within Broadcasting House: Orwell had worked there during World War Two. In the novel, Spears recognises that in order to solve Parson’s murder, he must understand how a radio drama is produced. Referencing Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Ericcson connects Death at Broadcasting House with Room 101 in George Orwell’s 1984 (1948): Gielgud and Marvell’s novel depicts ‘the traces of a crime committed in the interior of the modern’ and represents Broadcasting House as ‘not only a marvel of technology, but a scary place to be’ (2010: 43). As Ericsson notes, Orwell’s inspiration for Room 101 was a room within Broadcasting House: Orwell had worked there during World War Two.

The film is given some levity by some nicely humorous little touches. In one sequence, a male character, Bannister (Peter Haddon), sidles up to a woman and says, ‘I’m looking for Variety’. ‘Well, what’s “variety” to you is not to me’, the woman responds, moving away from the door in front of which she has been standing to reveal that it is the ladies’ lavatory. In another sequence, broadcaster Gillie Potter (playing himself) is accosted by two young autograph hunters as he enters the building. Potter asks if Lord Reith has signed the book. ‘Henry Hall signed it, sir’, one of the boys quips optimistically. ‘Never heard of him’, Potter responds dryly, walking away without offering his autograph. Cut status is difficult to determine here. The BBFC website lists the film’s original running time, as submitted in 1934, as 74:43 mins (roughly equivalent to 71:40 mins, accounting for PAL speedup). This DVD runs for 69:00 (including 30 seconds of BBFC certificate and the Studiocanal logo), which is a full two minutes short of the running time of the original release (as documented by the BBFC). This could mean that some footage is missing due to print damage, etc. However, without further evidence, this is impossible to determine.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The monochrome image is good, for the most part: it is detailed and contrast is strong. A couple of sequences show some moderate print damage and telecine wobble; but these are intermittent and not too distracting.

Audio

Audio is presented via a clear two-channel mono track. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole ‘extra’ is a stills gallery (0:46).

Overall

Death at Broadcasting House is an entertaining little thriller with some good humorous elements. The film contains some great performances and some very effective photography: after Parsons has been killed, we see his body lying prone on the floor; is face is in shadow, and the shadow of his killer passes over him. In another sequence, an orchestra plays; we see the in silhouette. Shortly after, Fleming is shown on the telephone, the camera shooting through the round porthole-style window of a door 0 simulating the ‘iris out’ effect, until the illusion is shattered by the door opening. Simon Elmes notes how remarkably similar the Broadcasting House of 1934 was to the Broadcasting House of 2012: ‘dial up on the internet Reginald Denham’s 1934 classic movie Death at Broadcasting House and again, for all its modish long-shadow cinematography, it’s the same rather cramped place I’ve known for 40 years. The film’s opening shot, panning down that gleaming, curving façade to where a taxi is depositing a contributor in front of the big bronze doors, could – give or take a security barrier and double yellow line – be mistaken for today’s version of the building’ (2013: 73-4). Death at Broadcasting House is also notable for featuring the first film appearance of the singer Elisabeth Welch, who sings ‘Lazy Lady’ in a sequence in which she her musical accompaniment is provided by pianist Ord Hamilton and guitarist Chappie D’Amato. The film is an enjoyable thriller, and this disc contains a good presentation of the main feature. It would have been nice to see more contextual material, however. References: Elmes, Simon, 2013: Hello Again: Nine Decades of Radio Voices. London: Random House Ericcson, Staffan, 2010: ‘The Interior of the Ubiquitous: Broadcasting House, London’. In: Ericcson, Staffan & Riegert, Kristina (eds), 2010: Media Houses: Architecture, Media and the Production of Centrality. New York: Peter Lang: 19-58 Ericcson, Staffan et al, 2010: ‘Introduction’. In: Ericcson, Staffan & Riegert, Kristina (eds), 2010: Media Houses: Architecture, Media and the Production of Centrality. New York: Peter Lang: 1-18 Sallis, Peter, 2008: The Limelight: The Autobiography. London: Hachette This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|