|

|

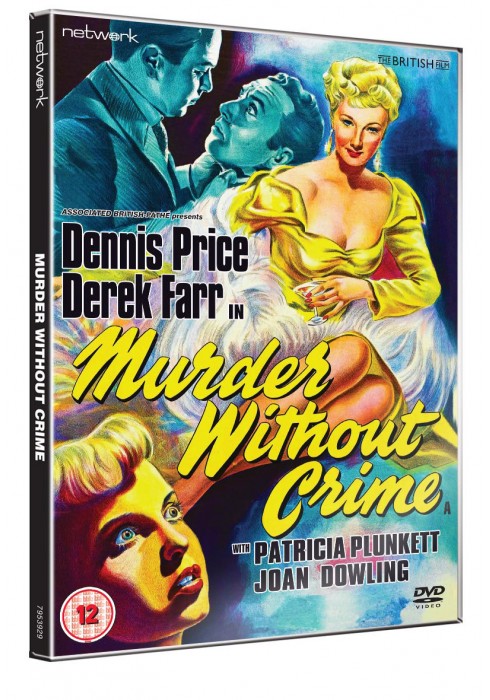

Murder Without Crime

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th August 2013). |

|

The Film

Murder Without Crime (J Lee Thompson, 1950)  Based on J Lee Thompson’s own highly successful stage play (first performed in 1942, and running for two years in London and one year on Broadway), Murder Without Crime (1952) was Thompson’s first film as a director. Thompson himself described the film as ‘a sort of Gothic melodrama’ that ‘wasn’t meant to be taken too seriously’ (quoted in Chibnall, 2000: 34). However, on reflection Thompson later stated that he ‘had everything going for me yet the film was not a success. Again, everything looked bleak’ (Thompson, 1996: 160). Nevertheless, he ‘discovered that I enjoyed directing’ and felt a greater sense of achievement on completing his second film, The Yellow Balloon (1953) (ibid.: 161). Thompson’s third film, Yield to the Night (1956), would consolidate the socially-conscious brand of filmmaking that was to become Thompson’s forte. Based on J Lee Thompson’s own highly successful stage play (first performed in 1942, and running for two years in London and one year on Broadway), Murder Without Crime (1952) was Thompson’s first film as a director. Thompson himself described the film as ‘a sort of Gothic melodrama’ that ‘wasn’t meant to be taken too seriously’ (quoted in Chibnall, 2000: 34). However, on reflection Thompson later stated that he ‘had everything going for me yet the film was not a success. Again, everything looked bleak’ (Thompson, 1996: 160). Nevertheless, he ‘discovered that I enjoyed directing’ and felt a greater sense of achievement on completing his second film, The Yellow Balloon (1953) (ibid.: 161). Thompson’s third film, Yield to the Night (1956), would consolidate the socially-conscious brand of filmmaking that was to become Thompson’s forte.

The film opens with a narrator who introduces us to the main characters: ‘moderately successful’ author Stephen (Derek Farr), his wife Jan (Patricia Plunkett), their landlord Matthew (Dennis Price), and good-time girl Grena (Joan Dowling), a twenty-two year old hostess at the Teneriffe nightclub in Piccadilly Circus. In Stephen and Jan’s flat, the couple argue: she is jealous after having found what Stephen describes as ‘a few letters, quite innocent ones. If they weren’t, you’d never have found them’. The argument escalates, and Stephen sends Jan packing, telling her to go to Gordon Winters, a long-time admirer of hers.  After Jan has left, Stephen bumps into Matthew; Matthew takes Stephen to the Teneriffe club and introduces him the Grena. Finding a sympathetic ear in Grena Stephen tells Grena about Jan: ‘She married not me, but an ideal’. They leave the club together, and a drunk Stephen takes Grena home to her flat. She has pills in her room; seeing her taking them, Stephen confiscates them (‘Are these for your nerves too, you silly little fool? [….] I’ll look after these’). After Jan has left, Stephen bumps into Matthew; Matthew takes Stephen to the Teneriffe club and introduces him the Grena. Finding a sympathetic ear in Grena Stephen tells Grena about Jan: ‘She married not me, but an ideal’. They leave the club together, and a drunk Stephen takes Grena home to her flat. She has pills in her room; seeing her taking them, Stephen confiscates them (‘Are these for your nerves too, you silly little fool? [….] I’ll look after these’).

Realising he has made a mistake, Stephen leaves Grena’s flat and returns home. However, she has followed him and demands to be let into his flat. She makes advances towards him and he kisses her. ‘You play better on home ground’, she says. However, Stephen retreats from Grena and tries to persuade her to leave his flat. He writes her a cheque. ‘Oh, so you think that’s all I am. You think you can buy me’, she responds angrily, slapping him. ‘My dear girl, you’re not doing a cabaret act. Put that down: you look ridiculous’, he tells her when she picks up a knife. A tussle ensues, and Grena is stabbed accidentally. Stephen stashes her body within an ottoman which he keeps in the living room of the flat. Shortly afterwards, Matthew comes up to see Stephen. Stephen tries to hide the body. ‘I was quite prepared to find you dangling somewhere [….] I heard a scream [….] The kind of scream a woman gives when she finds her lover dangling in the wardrobe’, Matthew says. He behaves suspiciously, and Stephen begins to think that Matthew is aware of Grena’s body being hidden within the ottoman.  Jan has a change of heart and returns to the flat. Stephen tells her about Grena: ‘It’s all a ghastly jumble. Nothing’s clear, not even now’, he says. Jan pleads with Stephen to go to the police; he refuses, saying that ‘this is my only chance’ to cover up the murder, ‘while Matthew is out of the way’. However, Matthew intrudes again, and Stephen asks Jan to retrieve some evidence of Grena’s presence at the flat whilst he takes care of Matthew. Matthew reveals the he knows Grena, who appears to be an ex-lover of Matthew’s, was in Stephen’s flat because he recognised her perfume. He also declares that he believes ‘when she [Grena] refused your advances, you attacked her mercilessly’, and he hopes that ‘Jan might find consolation in my arms. And believe me, Stephen, I’m an expert at consoling a woman in distress’. He attempts to blackmail Stephen, demanding that Stephen rent his downstairs flat for £1500 a month (‘It has advantages: a basement, where a man can work undisturbed, and a furnace, the large, old-fashioned type’). However, whilst Jan makes a major discovery in Matthew’s flat (Grena is still alive), Matthew unwittingly poisons himself when, suspicious of Stephen, he switches glasses with his host: Stephen has put a the pills he confiscated from Grena into his own glass, hoping to find his way out of this dilemma through suicide. Matthew unknowingly downs the lethal cocktail, and when he realises what has happened, he tells Stephen, ‘It was all a joke, Stephen: a terrible joke. Stephen, you’re not a murderer, but if I die…’ Jan has a change of heart and returns to the flat. Stephen tells her about Grena: ‘It’s all a ghastly jumble. Nothing’s clear, not even now’, he says. Jan pleads with Stephen to go to the police; he refuses, saying that ‘this is my only chance’ to cover up the murder, ‘while Matthew is out of the way’. However, Matthew intrudes again, and Stephen asks Jan to retrieve some evidence of Grena’s presence at the flat whilst he takes care of Matthew. Matthew reveals the he knows Grena, who appears to be an ex-lover of Matthew’s, was in Stephen’s flat because he recognised her perfume. He also declares that he believes ‘when she [Grena] refused your advances, you attacked her mercilessly’, and he hopes that ‘Jan might find consolation in my arms. And believe me, Stephen, I’m an expert at consoling a woman in distress’. He attempts to blackmail Stephen, demanding that Stephen rent his downstairs flat for £1500 a month (‘It has advantages: a basement, where a man can work undisturbed, and a furnace, the large, old-fashioned type’). However, whilst Jan makes a major discovery in Matthew’s flat (Grena is still alive), Matthew unwittingly poisons himself when, suspicious of Stephen, he switches glasses with his host: Stephen has put a the pills he confiscated from Grena into his own glass, hoping to find his way out of this dilemma through suicide. Matthew unknowingly downs the lethal cocktail, and when he realises what has happened, he tells Stephen, ‘It was all a joke, Stephen: a terrible joke. Stephen, you’re not a murderer, but if I die…’

The film’s similarities with Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) - based on Patrick Hamilton’s 1929 play (retitled Rope’s End for its Broadway production) - in which a body is similarly hidden in a chest in the flat of the murderers, should be evident from this synopsis. Thompson freely acknowledged the influence of Hitchcock’s Rope on Murder Without Crime: ‘I owe a lot to Rope, there’s no doubt about that’, he stated (quoted in Chibnall, op cit.: 34). In 1943, after early stage performances of Murder Without Crime, the American drama critic George Jean Nathan described Thompson’s play as ‘a mediocre paraphrase of Patrick Hamilton’s Rope’s End which, shown locally some ten or more years ago, was a superior example in kind’ (Nathan, 1944: 41). Thompson’s play, Nathan observed, sidestepped ‘the strict Leopold-Loeb essence of Hamilton’s play’ but ‘retain[ed] a liberal smell of it in the soi-distant character of the stygian friend’, Dennis Price’s Matthew (ibid.).  Matthew is an interesting character. In his book about Thompson, Chibnall describe’s Price’s Matthew as a ‘brother-in-acid to Waldo Lydecker [Clifton Webb] of Laura (Otto Preminger, 1944)’ who is ‘coded as gay by his clothing, demeanour and furnishings’ (op cit.: 32). Matthew, Chibnall states, ‘stalks the capacious rooms of his town house in an exaggerated state of ennui, clad in bow-tie and brocade dressing gown’ (ibid.: 32-3). Although late in the narrative, Matthew expresses desire for Stephen’s wife Jan and suggests a previous relationship with Grena, for Chibnall this ‘does little to dispel the impression of campness’ inherent within the set design and Dennis Price’s performance (ibid.: 33). Price has most of the best lines. When Stephen pours Matthew a whisky, he tells Matthew to ‘Say when’. ‘I never say “When”’, Matthew responds. Later, Stephen informs Matthew that ‘Jan’s coming back’. ‘How women chop and change. Why didn’t you tell me? I’d have brought daffodils or something’, Matthew says. Matthew is an interesting character. In his book about Thompson, Chibnall describe’s Price’s Matthew as a ‘brother-in-acid to Waldo Lydecker [Clifton Webb] of Laura (Otto Preminger, 1944)’ who is ‘coded as gay by his clothing, demeanour and furnishings’ (op cit.: 32). Matthew, Chibnall states, ‘stalks the capacious rooms of his town house in an exaggerated state of ennui, clad in bow-tie and brocade dressing gown’ (ibid.: 32-3). Although late in the narrative, Matthew expresses desire for Stephen’s wife Jan and suggests a previous relationship with Grena, for Chibnall this ‘does little to dispel the impression of campness’ inherent within the set design and Dennis Price’s performance (ibid.: 33). Price has most of the best lines. When Stephen pours Matthew a whisky, he tells Matthew to ‘Say when’. ‘I never say “When”’, Matthew responds. Later, Stephen informs Matthew that ‘Jan’s coming back’. ‘How women chop and change. Why didn’t you tell me? I’d have brought daffodils or something’, Matthew says.

Matthew essentially ‘pimps’ Grena out to Stephen; her casual attitude towards sex and her openness about her desire for Stephen seem to disturb him and code her as a femme fatale – one of many aspects of the film, including the use of low-key lighting and canted angles in the photography – that allude to American films noirs. ‘What about Millie?’, Stephen asks when, in Grena’s flat, their flirtation threatens to become more intimate. ‘We have our own friends, Millie and me. Sometimes we make it a party, and sometimes we don’t’, Grena asserts. However, her sexual rapaciousness seems to mask a deeper insecurity: when Stephen asks Grena if she is afraid of growing old, she tells him, ‘I’ll never grow old. The moment the men stop liking me, I’ll just hand in my chips’. This, along with her presumed addiction to the unnamed narcotics that Stephen confiscates from her, suggest she is as much a victim as a sexual predator – although these two categories are not, of course, mutually exclusive. Levity is added by the reflexive narration. The narrator is unnamed but addresses the audience directly; his tone is informal and spontaneous, strongly reminiscent of the narration that opens Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1948) (and Lionel Stander’s narration, delivered in the second person, that opens Allen Baron’s much later film noir Blast of Silence, 1960). ‘Good evening, ladies and gentlemen’, the narrator asserts as the film opens: ‘And if that sounds peremptory, […] well, story-telling isn’t my line. And heck, who hasn’t got a story anyway. But the truth is a perverted vein of impish humour leads me to while away an idle hour or so before I catch my plane back’. And so we learn from the narrator, whose accent identifies him as American, that he is sitting in an airport, apinning a yarn whilst waiting for a plane. This narration casts the whole film in an ironic light. As the film progresses, the narration becomes even more jaunty: when Jane leaves Stephen, the narrator declares, ‘Jan’s run out on him, and that’s okay by Steve. He’ll go someplace and get good and high, good and quick’. Later, when Jan decides to return to the flat and reunite with Stephen, the narrator notes dryly, ‘Sure it’s happened a million times. Young lovers’ quarrel. She stalks off to an admirer and ducks out; and he gets caught on the rebound and can’t’.  Steve Chibnall has noted that the narrator is ‘an unmistakeable echo of the narrator who opens the British version of The Third Man – sardonic and anonymous, an intriguing character whom we never meet’ (op cit.: 33-4). In both films, the respective narrators ‘introduce a protagonist who is naïve, vulnerable and out of his depth, and at the same time distance him from the audience’ (ibid.: 34). The American narrator, ‘like the noir touches in Bill McLeod’s cinematography, has the primary function of making a thinly disguised London stage play palatable to American cinema audiences’ (ibid.). Steve Chibnall has noted that the narrator is ‘an unmistakeable echo of the narrator who opens the British version of The Third Man – sardonic and anonymous, an intriguing character whom we never meet’ (op cit.: 33-4). In both films, the respective narrators ‘introduce a protagonist who is naïve, vulnerable and out of his depth, and at the same time distance him from the audience’ (ibid.: 34). The American narrator, ‘like the noir touches in Bill McLeod’s cinematography, has the primary function of making a thinly disguised London stage play palatable to American cinema audiences’ (ibid.).

In his book about Thompson, Steve Chibnall refers to Murder Without Crime as ‘confident but largely unadventurous’ (ibid.: 31). The film sidesteps the ‘taut, socially-concerned, realism’ that would become Thompson’s stock-in-trade, instead offering ‘another story of death in Soho which looks back to the rarefied hokum of earlier theatre work and adaptations like East of Piccadilly’ (ibid.). However, the film offers ‘a familiar J. Lee Thompson scenario of entrapment and the frantic search for a means of escape’ (ibid.: 31-2). Ultimately, Chibnall notes that the film is ‘a macabre entertainment with enough Grand Guignol to grip the spectators in the stalls and enough ironic self-awareness to please the more intellectual patrons in the circle’ The film is uncut and runs for 73:15 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in its original screen ratio of 1.33:1. Good contrast shows off the excellent noir-esque low-light photography: there’s good gradation in the mid-tones, with strong blacks.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track, which is entirely functional and has no issues. No subtitles are included, sadly.

Extras

None.

Overall

Murder Without Crime is an interesting, entertaining little crime film. However, it recycles familiar elements from other, similar, films – especially Hitchcock’s Rope and American films noirs. The canted angles, low-key lighting and femme fatale (Grena) all allude to US noir pictures of the period and, as Chibnall notes, there is a strong element of self-reflexivity within the film, both within the performances and in terms of set design and dialogue: the ‘film’s characters continually draw attention to their own theatricality: “stop dramatising yourself” Stephen orders Grena, who unsheathes an ornamental dagger like a silent-movie vamp before collapsing decoratively like a cover-girl from a cheap crime novelette’ (ibid.: 32). Price’s performance is a subtle camp delight, and Matthew is also given a sense of pathos by a brief exchange between Matthew and Stephen which retroactively colours some of Matthew’s behaviour in a different light: ‘Four years ago tonight, you came to live here’, he tells Stephen, ‘and I changed from being a well-to-do gentleman with a West End residence to landlord by necessity’. The room, Matthew states, was his father’s study, ‘a place of awe and terror and fear’. (This aspect of Matthew’s character seems to anticipate the characterisation of Carl Boehm’s Mark Lewis in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, 1960.) Ultimately, the film is interesting if unexceptional, and it is very different from Thompson’s later, more socially-driven, films. The presentation here is very good, but some contextual material would have been extremely welcome. References: Chibnall, Steve, 2000: British Film Makers: J Lee Thompson. Manchester University Press Nathan, George Jean, 1944: The Theatre Book of the Year, 1943-1944. New Jersey: Associated University Presses Thompson, J Lee, 1996: In: Garnett, Tay & Slide, Anthony (eds), 1996: Directing: Learning from the Masters. Maryland: Scarecrow Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|