|

|

Link

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (31st August 2013). |

|

The Film

Link (Richard Franklin, 1986)  Richard Franklin’s fourth horror film, Link followed Patrick (1978), Road Games (1981) and Psycho II (1983), underscoring Franklin’s focus on psychological horror in an era dominated by stalk-and-slash pictures – although all of Franklin’s horror films to this point could be said to refer obliquely to the conventions of the American ‘slasher’ film, subverting them in clever ways: in Link, for example, there is no mystery surrounding the identity of the killer – an ape, rather than ‘the shape’ (to use the nickname given to Michael Myers in John Carpenter’s Halloween, 1978) – which is revealed in the film’s title; and although the film’s climax has elements of the American stalk-and-slash film (the female protagonist is an archetypal ‘final girl’, and the film’s climax is essentially an extended chase sequence), unlike the bulk of American stalk-and-slash films, the majority of the picture takes place in broad daylight. In fact, Franklin once described Link as ‘an ironic spin on Michael Myers and the whole genre’ (Franklin, quoted in Muir, 2013: 523). Richard Franklin’s fourth horror film, Link followed Patrick (1978), Road Games (1981) and Psycho II (1983), underscoring Franklin’s focus on psychological horror in an era dominated by stalk-and-slash pictures – although all of Franklin’s horror films to this point could be said to refer obliquely to the conventions of the American ‘slasher’ film, subverting them in clever ways: in Link, for example, there is no mystery surrounding the identity of the killer – an ape, rather than ‘the shape’ (to use the nickname given to Michael Myers in John Carpenter’s Halloween, 1978) – which is revealed in the film’s title; and although the film’s climax has elements of the American stalk-and-slash film (the female protagonist is an archetypal ‘final girl’, and the film’s climax is essentially an extended chase sequence), unlike the bulk of American stalk-and-slash films, the majority of the picture takes place in broad daylight. In fact, Franklin once described Link as ‘an ironic spin on Michael Myers and the whole genre’ (Franklin, quoted in Muir, 2013: 523).

Link was based on an idea that had been suggested to Franklin by his landlord, the cinematographer Thomas Ackerman, who had presented Franklin with a spec script in 1979 (see Muir, op cit.: 523). Originally, Franklin was to have directed Link after Road Games, but in between Road Games and Link Franklin became involved in directing Psycho II and Cloak & Dagger (1984). However, the premise of Link stuck with Franklin, who was intrigued by the notion of a film about ‘the idea that animal [sic] could be acting like a man, acting like an animal’ (quoted in ibid.). Franklin has stated that Link is essentially a study in the belief ‘[t]hat we are all alike and different. That “civilization” (political correctness and the like) is a thin veneer—yet that one percent genetic difference makes a huge difference’ (quoted in Muir, op cit.: 521-2; emphasis in original). The film opens with a night-time sequence that parodies the ‘stalking’ sequences of the contemporaneous slasher films. Set in London, the opening sequence begins with a slow pan across city streets. A police car pulls up and shines a light towards the camera (the light briefly hits the lens) and, suddenly, we realise that we’re watching the sequence from the point of view of an animal (presumably Link) as it runs away from the scene and climbs a trellis.  The subjective structure of the sequence is broken by a shot which takes us inside the bedroom of a little girl. She stares at her net curtains, which are blowing in the breeze from the open window. Downstairs, her parents watch television. The film they are watching is Josef Von Sternberg’s 1932 film Blonde Venus: it is the first number performed by Marlene Dietrich’s character, a cabaret star, who appears on stage amongst a group of chorus girls in a gorilla suit. The illusion is shattered as Dietrich removes, first, the suit’s gloves and then the head of the suit (Franklin cuts away from the scene just before Dietrich begins sing ‘Hot Voodoo’). Franklin’s use of this sequence is ironic inasmuch as, unlike many earlier films featuring apes, Link’s apes are played by… well, apes rather than stop-motion creatures or men (and women) in monkey suits. In The A to Z of Horror Cinema, Peter Hutchings notes that apes were ‘stock figures in American horror films from the 1920s to the 1950s’ (2009: 16), featuring in films such as King Kong (Ernest B Schoedsack & Merian C Cooper, 1933), Murders in the Rue Morgue (Robert Florey, 1932) and the the three film adaptations of Ralph Spence’s play The Gorilla (Alfred Santell, 1927; Bryan Foy, 1930; Allan Dwan, 1939). The vast majority of these films featured apes represented by actors wearing ape suits, a plot also seen in later horror films featuring apes such as Antonio Margheriti’s La morte negli occhi del gatto (Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eye, 1973). The subjective structure of the sequence is broken by a shot which takes us inside the bedroom of a little girl. She stares at her net curtains, which are blowing in the breeze from the open window. Downstairs, her parents watch television. The film they are watching is Josef Von Sternberg’s 1932 film Blonde Venus: it is the first number performed by Marlene Dietrich’s character, a cabaret star, who appears on stage amongst a group of chorus girls in a gorilla suit. The illusion is shattered as Dietrich removes, first, the suit’s gloves and then the head of the suit (Franklin cuts away from the scene just before Dietrich begins sing ‘Hot Voodoo’). Franklin’s use of this sequence is ironic inasmuch as, unlike many earlier films featuring apes, Link’s apes are played by… well, apes rather than stop-motion creatures or men (and women) in monkey suits. In The A to Z of Horror Cinema, Peter Hutchings notes that apes were ‘stock figures in American horror films from the 1920s to the 1950s’ (2009: 16), featuring in films such as King Kong (Ernest B Schoedsack & Merian C Cooper, 1933), Murders in the Rue Morgue (Robert Florey, 1932) and the the three film adaptations of Ralph Spence’s play The Gorilla (Alfred Santell, 1927; Bryan Foy, 1930; Allan Dwan, 1939). The vast majority of these films featured apes represented by actors wearing ape suits, a plot also seen in later horror films featuring apes such as Antonio Margheriti’s La morte negli occhi del gatto (Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eye, 1973).

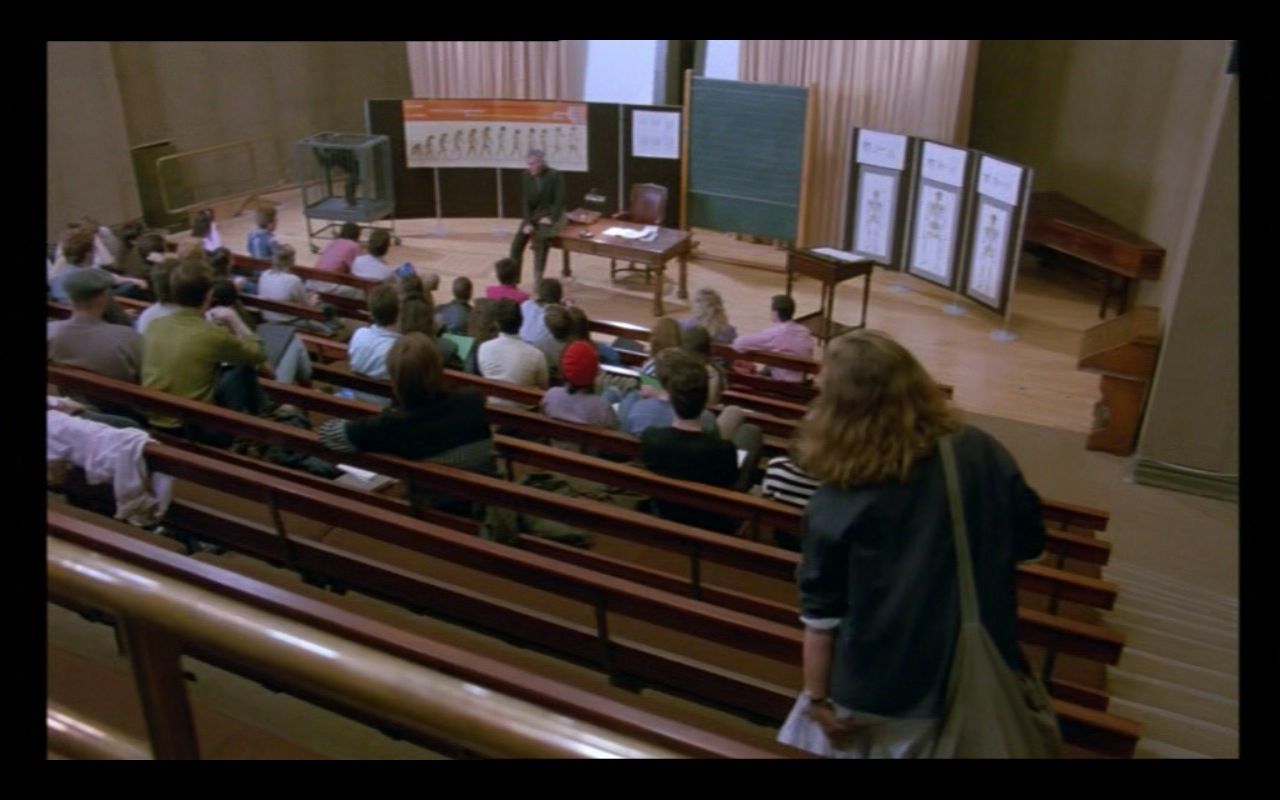

However, as Hutchings notes, after the 1970s ‘modern horror [made] little use of the ape-centred horror narrative’ (op cit.: 16). The few films which have focused on apes have presented the creatures ‘in more realistic terms, with real apes deployed and not a gorilla suit in sight’ (ibid.). As Hutchings notes, a trio of horror films featuring real apes appeared in the late-1980s: Franklin’s Link; Dario Argento’s Phenomena (1985), which features a chimpanzee who wields a straight-razor (a fact prominently featured on Palace Video’s famous artwork for the film’s UK VHS release, retitled Creepers); and George A Romero’s Monkey Shines (1988). Romero’s film is the closest in spirit to Link, inasmuch as it features a domesticated ape (a Capuchin monkey named Ella) whose behaviour increasingly exhibits repressed violent tendencies. Muir states that it is ‘interesting that two movies in the second half of the 1980s, Link and George Romero’s Monkey Shines (1988), attempted to tabulate the relationship between simian and man and gaze at the similarities and differences between species. Both films also bring the apes into domestic human settings—our turf!—and one senses that Link and Monkey Shines, each in its own way, suggest that perhaps apes and humans can’t really get along; that critical misunderstandings occur in creatures that are so very similar, but different in some important ways’ (op cit.: 522). The little girl screams. Her parents console her: ‘It’s just a nasty old dream they tell her’. A horizontal wipe (just one of a series of unusual editing techniques that Franklin uses in this film) takes us upstairs onto the roof of the building. Caged pigeons on the roof have been killed, as has a domestic cat. A crane shot which takes us across the roof and up the chimney stack reveals in the distance the London College of Sciences, which is where, the next day, the chief human characters of the film are introduced: Jane Chase (Elisabeth Shue) and Dr Steven Phillip (Terence Stamp). Dr Phillip offers Jane, a zoology student, a summer job working at his country estate, aiding him with the three apes under his care: Imp, Voodoo and Link, a former circus ape trained to perform as ‘Link, Master of Fire’. However, Link soon stages a coup which results in the death of Dr Phillip, which through his ingenuity Link manages to obscure from Jane. What follows is essentially an extended chase sequence in which Link, infatuated with Jane, pursues the young student both inside and outside the country estate.  When Jane first encounters Dr Phillip, it is in a lecture theatre where he is delivering a lecture on the intelligence of apes. Phillip’s comments warn the students (and the audience) not to take apes’ intelligence for granted. ‘He could give some of you a run for your money’, he says, referring to Imp, who is in a cage within the lecture theatre. One of the students asserts that ‘Man is the only species that makes war on his own kind’, but Phillip corrects him, asserting the cruelty of apes: ‘No. It used to be fashionable to think that [….] Except in 1979 in Tanzania, [primatologist] Jane Goodall observed chimps hunting in groups, kidnapping, murdering, even eating their own babies. Until then, we thought they were vegetarian’. In this sequence, Phillip also outlines the strength of apes: ‘Don’t let his [Imp’s] size fool you’, he tells his students: ‘he’s strong enough to thrown any one of you across the room. Of course, he isn’t very cultured: he doesn’t give a damn about the history of the world, the state of the economy. What he cares mainly about is bananas’. When he asks Jane if she can identify ‘one simple difference between Imp and humans’, she responds by asserting that it has ‘something to do with civilisation’. Phillip confirms her statement as accurate before the lecture is interrupted. When Jane first encounters Dr Phillip, it is in a lecture theatre where he is delivering a lecture on the intelligence of apes. Phillip’s comments warn the students (and the audience) not to take apes’ intelligence for granted. ‘He could give some of you a run for your money’, he says, referring to Imp, who is in a cage within the lecture theatre. One of the students asserts that ‘Man is the only species that makes war on his own kind’, but Phillip corrects him, asserting the cruelty of apes: ‘No. It used to be fashionable to think that [….] Except in 1979 in Tanzania, [primatologist] Jane Goodall observed chimps hunting in groups, kidnapping, murdering, even eating their own babies. Until then, we thought they were vegetarian’. In this sequence, Phillip also outlines the strength of apes: ‘Don’t let his [Imp’s] size fool you’, he tells his students: ‘he’s strong enough to thrown any one of you across the room. Of course, he isn’t very cultured: he doesn’t give a damn about the history of the world, the state of the economy. What he cares mainly about is bananas’. When he asks Jane if she can identify ‘one simple difference between Imp and humans’, she responds by asserting that it has ‘something to do with civilisation’. Phillip confirms her statement as accurate before the lecture is interrupted.

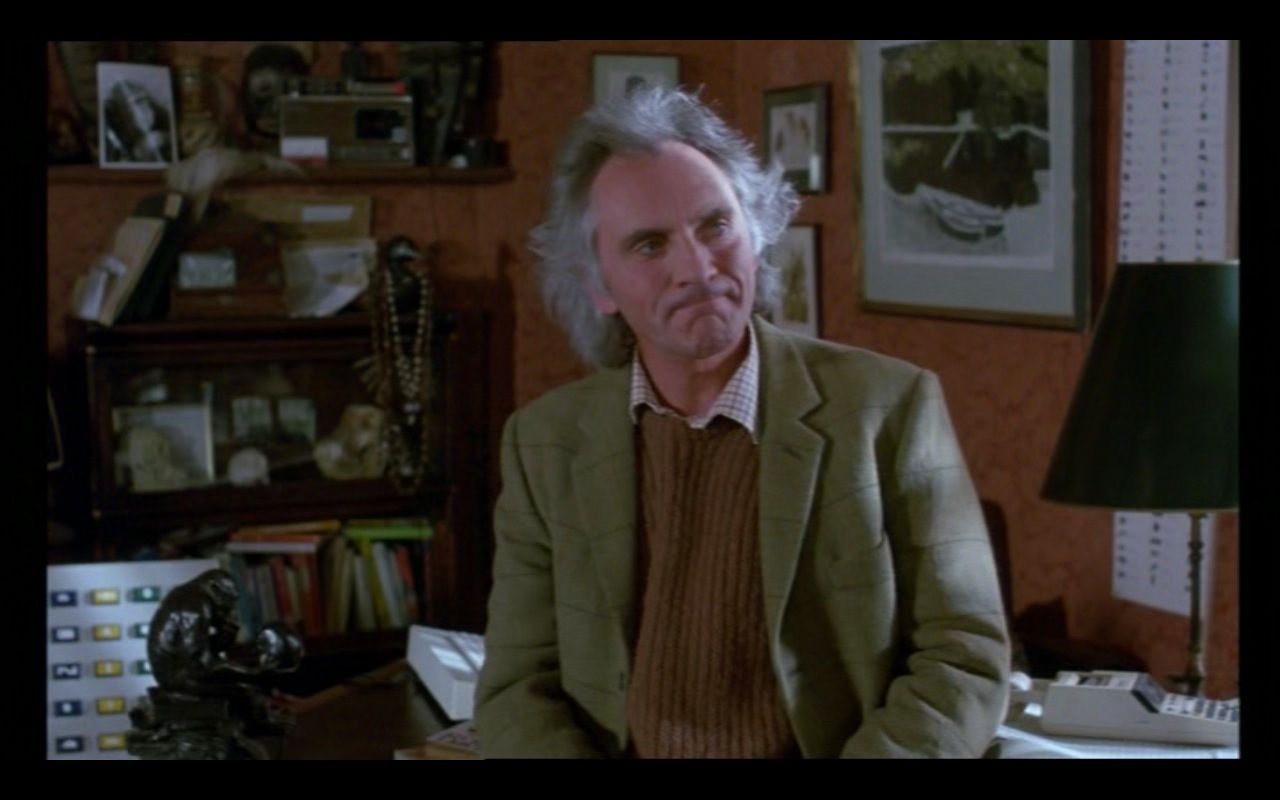

Phillip’s attitude towards Jane carries a subtext of barely-concealed desire, which may simply be a product of Stamp’s lazily seductive screen presence – something mined by his famous role in Pasolini’s Teorema (Theorem, 1968), for example. (Muir says that Stamp plays his character ‘with elegant pomposity’ (op cit.: 522).) When Jane first approaches Phillip, in response to his advertisement requesting help, he tells her that he was really looking for ‘sperm specimens’ but instead, in a moment of prime sexism, asks her if she can ‘cook, clean, stuff like that’. When she responds in the affirmative, he offers her a job with ‘accommodation and board and, let’s say, forty pounds a week?’ She agrees. Later, at Northfield Grange (Phillip’s country estate), one of the chimps bothers Jane. ‘He just wants to get up your skirt’, Phillip warns her, a glint in his eye. Later, when Phillip refers to Voodoo as ‘a sexually immature animal’, Stamp delivers the line in a very deliberate manner, suggesting he may also be referring to the young student Jane. After Link kills Phillip (his rival for Jane’s affections?), his behaviour suggests an unleashing of the desire that seemed to be repressed within the loner Phillip. When Jane takes a shower (a sequence which is jarring for its nudity from Shue), Link watches her lasciviously as she enters the bathroom wearing a towel. After she has warned him to go away, closed the door and dropped the towel, Link pushes the bathroom door opens and stands in the doorway of the room, eyeing Jane up and down.  Prior to his death at the hands of Link, Phillip warns Jane that there are ‘just a few rules that you have to remember’ whilst caring for the apes: ‘One, you’re the dominant species. You must never, ever treat them as equals. Two, don’t ever let anything escalate. Always forgive them, whatever they do. Three, don’t get involved in their squabbles. They sort them out’. As the film progresses, Jane will break all of these rules: for example, intervening in a squabble between Imp and Link. The device of the ‘rules’ which must be followed and which, when broken, lead to an escalation of previously repressed behaviour within Link, functions in a similar way to the rules presented to Randall Peltzer (Hoyt Axton) as he buys the Mogwai Gizmo for his son Billy (Zach Galligan): ‘Look Mister, there are some rules that you've got to follow [….] First of all, keep him out of the light. He hates bright light, especially sunlight: it'll kill him. Second, don't give him any water, not even to drink. But the most important rule, the rule you can never forget: no matter how much he cries, no matter how much he begs, never feed him after midnight’. Prior to his death at the hands of Link, Phillip warns Jane that there are ‘just a few rules that you have to remember’ whilst caring for the apes: ‘One, you’re the dominant species. You must never, ever treat them as equals. Two, don’t ever let anything escalate. Always forgive them, whatever they do. Three, don’t get involved in their squabbles. They sort them out’. As the film progresses, Jane will break all of these rules: for example, intervening in a squabble between Imp and Link. The device of the ‘rules’ which must be followed and which, when broken, lead to an escalation of previously repressed behaviour within Link, functions in a similar way to the rules presented to Randall Peltzer (Hoyt Axton) as he buys the Mogwai Gizmo for his son Billy (Zach Galligan): ‘Look Mister, there are some rules that you've got to follow [….] First of all, keep him out of the light. He hates bright light, especially sunlight: it'll kill him. Second, don't give him any water, not even to drink. But the most important rule, the rule you can never forget: no matter how much he cries, no matter how much he begs, never feed him after midnight’.

The film is presented without cuts. This is, however, the shorter US version of the film (99:29 PAL). Approximately 13 minutes were excised by the film's US distributors (Universal and EMI). The version released to cinemas in various European countries is significantly longer, featuring a different opening sequence and apparently expanding all of the scenes featuring Terence Stamp's character. (This version was released in UK cinemas with a running time of 115:47 - see the BBFC's entry on the film.)

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1, with anamorphic enhancement. Photographically, the film is very interesting and makes strong use of wide-angle lenses to distort perspective. There is a slight softness to the image at times; this is more than likely a product of the original photography – the film makes much use of natural light.

Some other aspects of the shooting of the film are very interesting. Several sequences which are shot from the apes’ perspective, including the murder of Phillip by Link, seem to feature dropped frames, resulting in curiously jerky onscreen movement. Frankin also uses some archaic editing techniques – including wipes – that add a sense of reflexivity to the film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital two-channel track with some subtle surround encoding which comes alive when it’s needed to, mostly showing off Goldsmith’s superb score.

Extras

Extras include a trailer (1:26), a teaser trailer (43s) and a stills gallery (2:43).

Overall

Link was apparently a difficult shoot for Franklin, not due to the apes but rather due to the English crew, who Franklin said were ‘very slow and difficult’ (quoted in Muir, op cit.: 523). It is an interesting film which explores the relationships between humans and the animal world. Sadly, the film was poorly distributed on its original release and never achieved the success it arguably deserved: in distribution, ‘EMI went belly up’ and ‘Cannon inherited the film and those guys were absolute bozos’ (Franklin, quoted in ibid.: 523). This DVD contains a very handsome presentation of the film, but unfortunately it is the shorter US version of the picture. The longer European cut has been released on DVD by StudioCanal in France, but sadly that release is not English-friendly. Link was apparently a difficult shoot for Franklin, not due to the apes but rather due to the English crew, who Franklin said were ‘very slow and difficult’ (quoted in Muir, op cit.: 523). It is an interesting film which explores the relationships between humans and the animal world. Sadly, the film was poorly distributed on its original release and never achieved the success it arguably deserved: in distribution, ‘EMI went belly up’ and ‘Cannon inherited the film and those guys were absolute bozos’ (Franklin, quoted in ibid.: 523). This DVD contains a very handsome presentation of the film, but unfortunately it is the shorter US version of the picture. The longer European cut has been released on DVD by StudioCanal in France, but sadly that release is not English-friendly.

References: Hutchings, Peter, 2009: The A to Z of Horror Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Muir, John Kenneth, 2013: Horror Films of the 1980s. London: McFarland This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|