|

|

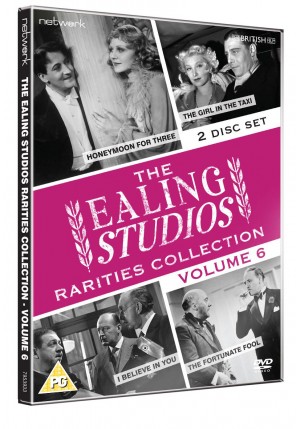

Ealing Studios Rarities Collection, Volume 6 (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th September 2013). |

|

The Film

Ealing Studios Rarities, Vol 6 Honeymoon for Three (Leo Mittler, 1935)  The first film in this sixth volume of Network’s Ealing Studios Rarities line is Leo Mittler’s light musical comedy Honeymoon for Three (1935), featuring a starring role for Stanley Lupino. By this stage of his career, Lupino was still a fairly major draw for audiences of British musical comedies, and this film provides a solid vehicle for his brand of lightweight comedy. As Harry Stone notes, Lupino ‘had a cockney perkiness which had a wide appeal and provided a common denominator between stalls and gallery’ (2009: 85). Lupino has a very likeable screen presence in all of his films, and this is fully evident here. The first film in this sixth volume of Network’s Ealing Studios Rarities line is Leo Mittler’s light musical comedy Honeymoon for Three (1935), featuring a starring role for Stanley Lupino. By this stage of his career, Lupino was still a fairly major draw for audiences of British musical comedies, and this film provides a solid vehicle for his brand of lightweight comedy. As Harry Stone notes, Lupino ‘had a cockney perkiness which had a wide appeal and provided a common denominator between stalls and gallery’ (2009: 85). Lupino has a very likeable screen presence in all of his films, and this is fully evident here.

Lupino plays Jack Denver. The film opens in a nightclub where Denver, introduced whilst miming a game of draughts played with champagne bottles, sings ‘Make Hay While the Moon Shines’. When the nightclub closes, a drunken Denver staggers through the streets. (He attempts to use a taxi. ‘Home’, he demands; ‘Where to?’, the driver asks; ‘That’s my business’, Denver responds before being dumped by the driver.) In the morning, Yvonne Daumery (Aileen Marson) awakens to find Denver sleeping on the floor of her flat: Yvonne lives directly above Denver, and in his drunken state he has mistaken her flat for his own. When Yvonne’s father (Dennis Hoey) arrives, Denver escapes from Yvonne’s flat but is stopped by a policeman. ‘Now look here: I’ve got an appointment’, Denver tells the policeman. ‘With me’, the policeman adds before escorting Denver to Yvonne’s flat where matters become even more complicated as the policeman reveals to a shocked Yvonne (and her even more shocked father) that, in order to escape charges, Denver has claimed to be Yvonne’s husband. Yvonne’s father insists that she and Denver get married, which angers Denver’s real fiancé Raymond Dirk (Jack Melford). After their wedding, Denver and Yvonne go on their honeymoon, where Denver shares a room with Raymond. After the honeymoon, Denver and Yvonne plan to arrange a divorce so that she may marry Raymond. The film is utterly predictable: as the viewer may suspect, Yvonne begins to recognise the flaws in Raymond’s character and gradually warms to the effervescent Denver, who has fallen in love with Yvonne. When she asks on what grounds they should divorce, Denver tells Yvonne, ‘Well say I snore [….] Tell them I bite my nails’. She tells him to be serious. Denver suggests negligence: ‘Tell them I’ve never kissed you, never held your hand, haven’t danced with you, we’ve occupied separate cabins’. ‘Wouldn’t that make you look a cad?’, she asks. ‘Oh, no. One look at you, and it’ll make me look an idiot’, Denver says. Ultimately, it’s a sentimental, predictable film, but through the dialogue and the warmth of Lupino’s screen presence, Honeymoon for Three has much to offer. The film is uncut and runs for 74:34 mins (PAL). I Believe in You (Michael Relph, Basil Dearden, 1952)  A film that underscores the social conscience and the focus on outsiders that were at the heart of much of Basil Dearden’s work, I Believe in You (1952) is a very good example of the post-war ‘social problem film’. Like many social problem films, including famous examples such as Dearden’s own The Blue Lamp (1950), I Believe in You revolves around issues of youth and criminality. A film that underscores the social conscience and the focus on outsiders that were at the heart of much of Basil Dearden’s work, I Believe in You (1952) is a very good example of the post-war ‘social problem film’. Like many social problem films, including famous examples such as Dearden’s own The Blue Lamp (1950), I Believe in You revolves around issues of youth and criminality.

Loosely based on Sewell Stokes’ memoir Court Circular: Experiences of a London Probation Officer (1950), the film has been said to have been one of Dearden’s favourite of his own films (see Burton & O’Sullivan, 2009: xv). Through the character of Norma (Joan Collins), the film tackles the growing awareness during the 1950s of female juvenile delinquency. It opens in a court where probation officer Henry Phipps (Cecil Parker) is called to speak on behalf of a young man, Johnson. In voiceover, Phipps tells us that ‘Only about a year ago I was what once was called “a man of leisure”’. He returned to England from the colonies, ‘but somehow I wasn’t enjoying the leisure to which I’d once looked forward’ and felt that he ‘must do… something’. Thus the bulk of the film takes place as an extended analepsis, beginning with Phipps’ first encounter with Norma. Looking out of the window of his flat, Phipps sees a motor accident in the street outside. A girl, Norma, flees from the scene and Phipps encounters her in the stairwell of the building in which he lives. Letting her into his flat, he listens to Norma’s story as she tells him that her tearaway boyfriend (who we later learn is Jordie Bennett, played by Laurence Harvey) stole the car that was involved in the accident. Learning that Norma has been ‘in trouble before’, Phipps calls her probation officer, Matty Mathieson (Celia Johnson). Mathieson arrives at Phipps’ flat and takes charge of Norma. During his encounter with Phipps, he asks her about her work as a probation officer. She tells him that although she is never quite sure whether or not she ‘likes’ her job, ‘it is quite worthwhile’. After attending Norma’s hearing, Phipps reflects in voiceover that, ‘I knew then that this was the kind of job I wanted, a worthwhile job, the kind of job I felt sure I could do’. Beginning work in the probation service, Phipps soon begins to realise the difficulty of the role. Phipps’ work is shown in detail. His wanderings through the streets of London, in the service of his clients, are depicted, cinema of process-like, through montage. In his narration, Phipps says his first weeks as a probation officer ‘took me to places I never knew existed’: parts of London drenched in poverty that he hadn’t seen before. Consequently, he developed ‘sore feet, seasoned feet’, and reflects that ‘It seemed that a lot of them didn’t want to be helped, no matter how hard one tried’. However, he finds his approach aided by Matty, who informs him it is important to remember that ‘You don’t plan for people; you plan with them’. ‘Why don’t you meet them on their own level, rather than gazing down at them?’, she tells him. Phipps also finds himself playing a pivotal role in the life of Norma, who becomes torn between her new boyfriend, Charlie Hooker (Harry Fowler), and Jordie Bennett (who has been released from prison). Hooker is a young man who, under Phipps’ guidance, has – like Norma – vowed to reform himself. However, Norma’s fascination with ‘bad boy’ Bennett threatens to undo Phipps’ good work and throw both Norma and Hooker back into a life of crime. I Believe in You is a fascinating film that highlights the work of the probation service. Sometimes the film, as with some of the other social problem pictures, can become a little didactic (as when Phipps asserts that ‘the probation service was very understaffed’) but for the most part the film highlights its social issues in a subtle, even-handed manner. A significant number of Phipps’ clients show the traits of, to use modern parlance, institutionalised personalities. One of Phipps’ first clients is a young sailor who, drunk, was found to be sleeping the door of the local Co-Op. Angered by the officer arresting him, the young man assaulted the officer. When Phipps asks the young man why he responded so aggressively, he is told, ‘I don’t know. When I’m at sea, I’m all right’. Very nicely shot, with some almost noir-ish high contrast chiaroscuro photography, I Believe in You has an episodic structure; like many of the social problem films, it takes a journalistic approach that, as noted above, can sometimes border on the didactic. It is arguably more complex than Rearden’s The Blue Lamp in its examination of the difficulties both Norma and Hooker face in their attempts to reform their behaviour, and the impact of Hooker’s poverty-stricken background in determining the actions that led to his arrest (Hooker’s father died during the war, and he has a turbulent relationship with his stepfather). On the other hand, in the character of Bennett the film resorts to stereotypes: Bennett is an irredeemable delinquent and a corruptor of comparatively ‘innocent’ youths such as Norma and Hooker; a biker, Bennett’s criminality seems tied up with his associations with popular music (he hangs out in clubs and listens to jukeboxes) and his easy sexuality (in one scene, it is suggested that he and Norma sleep together the day before her date with Hooker). Consequently, whilst I Believe in You offers a somewhat progressive view of both the probation service and juvenile delinquency (especially female delinquency), through the character of Bennett it also offers a slightly patronising and stereotypical view of youth culture. The film is uncut and runs for 94:53 mins (PAL) Disc Two The Fortunate Fool (Norman Walker, 1933)  Norman Walker’s The Fortunate Fool (1933) opens on a bench: a wealthy man, later revealed to be writer Jim Falconer (Hugh Wakefield), sits between two homeless people: Rose (Sara Allgood) and ex-boxer Batty (Arthur Chesney). Falconer offers the pair what he claims to be his last cigarette. ‘I won’t need it’, he reflects: ‘I have no home now’. He claims to have been thrown out of his club for cheating at cards; the damage to his reputation has led him to commit suicide (he is carrying a revolver with which he suggests he might shoot himself). ‘Lots of people talk like philosophers and live like fools’, he tells his new friends of a very different social class, before quoting Epicurus: ‘It is bad to live in necessity, but there is no necessity to live in necessity’. ‘You and me’s the same’, Batty observes: they are both losers in life, although Falconer has had different opportunities to Batty: ‘It’s in the blood’, Batty tells Falconer, persuading the wealthy man to put away his revolver. Norman Walker’s The Fortunate Fool (1933) opens on a bench: a wealthy man, later revealed to be writer Jim Falconer (Hugh Wakefield), sits between two homeless people: Rose (Sara Allgood) and ex-boxer Batty (Arthur Chesney). Falconer offers the pair what he claims to be his last cigarette. ‘I won’t need it’, he reflects: ‘I have no home now’. He claims to have been thrown out of his club for cheating at cards; the damage to his reputation has led him to commit suicide (he is carrying a revolver with which he suggests he might shoot himself). ‘Lots of people talk like philosophers and live like fools’, he tells his new friends of a very different social class, before quoting Epicurus: ‘It is bad to live in necessity, but there is no necessity to live in necessity’. ‘You and me’s the same’, Batty observes: they are both losers in life, although Falconer has had different opportunities to Batty: ‘It’s in the blood’, Batty tells Falconer, persuading the wealthy man to put away his revolver.

Later, introducing himself as ‘an author – a very bad one’, Falconer repeats his act, sitting next to a young woman (Helen, played by Joan Wyndham) who, instead of persuading him not to kill himself, instead encourages him to do so and suggests that she wishes to commit suicide too. To both Helen and Batty, Falconer offers the opportunity to meet him at his home, where he offers both somewhere to stay. (‘I’m not terribly sure about the cove who’s sleeping over there’, Falconer tells Helen, referring to Batty: ‘So lock your door, won’t you’.) However, it doesn’t take long for Helen to discover that Falconer – who has hired her as his secretary – has told a different story to both her and Batty. She confronts Falconer, who tells her that he simply wanted to win Batty’s confidence. Meanwhile, Batty becomes concerned because he feels as if he is losing his identity by living in the rich man’s house. ‘Well, that’s what comes of helping God’s creatures’, Falconer notes as Batty leaves the building. Shortly after, Helen, with whom Falconer has begun to fall in love, leaves his employ after becoming tired of his deceit. Falconer realises his feelings for Helen and seeks to win her back. The Fortunate Fool is held together by some good performances but ultimately it’s vision of the British class system is terribly dated and Falconer is quite an unlikeable character: his relationships with Batty and Helen are built on deceit, and there’s a sense that Falconer feels that it is acceptable to ‘toy’ with the lower classes. A flaneur of sorts, wandering the streets of London for inspiration for his writing, Falconer claims that he met Batty and Helen whilst ‘look[ing] for copy. I was hard-up for something to write about, so I decided to take a slice out of life. Then this girl came along’. The script seemingly unironically presents his patronising attitude towards those less fortunate than himself as acceptable. Despite this, however, there is some delicious dialogue: ‘Have you ever been in love?’, Falconer asks his manservant Marlowe (Bobbie Comber). ‘No, sir, but I hear it makes people act very peculiar’, is the response. Later, when Falconer charges Marlowe with the task of tracking down Batty, Marlowe finds Batty in a pub. ‘He’s a philanthropist’, Marlowe informs Batty, referring to Falconer. ‘There’s nothing wrong with my corns’, Batty asserts in response. Nevertheless, despite the nicely-observed dialogue and character detail, the film goes nowhere and the deeply reactionary ideas about social class may serve to alienate some viewers: ‘Have you noticed that when a man tries to live a life with people not of his own class, it always ends in trouble’, Mildred (Elizabeth Jenns), Falconer’s fiancée, notes. The film is uncut and runs for 73:06 mins (PAL). The Girl in the Taxi (André Berthomieu, 1937)  Film musicals were popular during the 1930s, but the genre wasn’t entirely respectable; on the other hand, light operetta had a credibility and kudos that the more popular musicals were seen to lack. This film, The Girl in the Taxi, was loosely based on an English-language adaptation of the stage operatta Die keusche Susanne (1910); by the time of Andre Berthomieu’s 1937 adaptation of the stage play, the story had been filmed a number of times – a short film adaptation in 1911 was followed by two silent feature film adaptations (one American, one French), as The Girl in the Taxi (Lloyd Ingraham) and as Chaste Susanne (Richard Eichberg, 1926). (Berthomieu appears to have shot a French-language version of the same film, under the title La chaste Suzanne, during the same year.) Film musicals were popular during the 1930s, but the genre wasn’t entirely respectable; on the other hand, light operetta had a credibility and kudos that the more popular musicals were seen to lack. This film, The Girl in the Taxi, was loosely based on an English-language adaptation of the stage operatta Die keusche Susanne (1910); by the time of Andre Berthomieu’s 1937 adaptation of the stage play, the story had been filmed a number of times – a short film adaptation in 1911 was followed by two silent feature film adaptations (one American, one French), as The Girl in the Taxi (Lloyd Ingraham) and as Chaste Susanne (Richard Eichberg, 1926). (Berthomieu appears to have shot a French-language version of the same film, under the title La chaste Suzanne, during the same year.)

The original English stage adaptation was in part the brainchild of impresario George Edwardes, a key figure in popularising light opera. Edwardes was, Peter Bailey has argued, ‘the man most responsible for the exaltation of the woman as girl’, leading to ‘an endless string of show titles’ with the word ‘girl’ in their title (The Girl in the Taxi, A Gaiety Girl, The Girl Behind the Counter) (1996: 38). The film opens with a meeting of a committee to decide who will be awarded the Prize of Virtue. The chairman, Baron des Aubrais (Lawrence Grossmith), the award – which the committee has agreed is to be given to Suzanne Pommarel (Frances Day) – confirms, the Baron claims, the thesis that virtue is the product ‘of hereditary influence’ and is ‘the reward of a pure and blameless life’. This provokes a disagreement with another member of the committee, who asserts, ‘Rubbish. Absolute rubbish. What has heredity got to do with nature?’ To this, the Baron invites the other man to the prison cells where, he claims, the men are not incarcerated due to ‘vice’ but rather due to ‘heredity’. Meanwhile, over dinner the Baron’s daughter Jacqueline (Jean Gillie) asks after a young man, Rene (Henri Garat); the Baron reminds her that matrimony is ‘a serious business’ and asks his son Hubert (Mackenzie Ward) to produce a report on the young man, ‘his family and his morals’, as a means of gauging his suitability as a mate for Jacqueline. Hubert invites the married Suzanne Pommarel to a dinner, away from the suspicious gaze of her jealous husband Emile (John Deverell). Meanwhile, the Baron is dining in the same restaurant: he is an adulterer, as immoral as those against whom he preaches. Of course, the immorality of Pommarel and the Baron are bound to be discovered by the other characters, and what follows is essentially a comedy of manners that the Irish Film Censor saw fit to ban on its original release, asserting that, ‘[t]his is the typical film farce dealing with the amorous adventures of a father and son and their relations with a deceiving wife who gets a prize for virtue. There are suggestive songs and rather indecent situations and double meaning jokes. A certificate cannot be granted’ (Irish Film Censors’ Records). (The film was eventually released in Ireland after an appeal.) The Girl in the Taxi is lightweight and mildly entertaining, but ultimately it is not particularly memorable. The film is uncut and runs for 66:03 mins (PAL). DISC ONE: ‘Honeymoon for Three’ (Leo Mittler, 1935) (74:34) ‘I Believe in You’ (Michael Relph, Basil Dearden, 1952) (94:53) Stills Gallery DISC TWO: The Fortunate Fool (Norman Walker, 1933) (73:06) The Girl in the Taxi (André Berthomieu, 1937) (66:03)

Video

All of the films are presented in their original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. Honeymoon for Three demonstrates some good contrast and detail, with natural wear and tear throughout the picture. I Believe in You has very strong contrast and a subtly noir-ish aesthetic, with some scenes dominated by high contrast photography: the faster film stocks of the 1950s also offer scope for a more naturalistic, less (obviously) studio-bound and studio-lit aesthetic, in keeping with the realism of Dearden’s filmmaking style during this period. The Fortunate Fool and The Girl in the Taxi have a more diffuse look, with weaker contrast levels – most likely a product of the original productions rather than a ‘flaw’ in this presentation.

Audio

All of the films are presented with a two-channel mono track. None of the films have any major issues in terms of their audio, although The Fortunate Fool evidences the most ‘worn’ audio track (with hissing and pops and crackles throughout). Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The first disc includes a stills gallery.

Overall

Network’s Ealing Studios Rarities collections are a delight, gathering together a diverse array of films that have proven quite difficult to see. This release is a little uneven: the films on disc one (Honeymoon for Three and I Believe in You) are very good; the films on disc two (The Fortunate Fool and The Girl in the Taxi) are less impressive. I Believe in You is the clear standout of this particular volume. All of the films get a good presentation here. Fans of the previous Ealing Studios Rarities volumes will find this set highly satisfying. This review has been kindly sponsored by:  References: Bailey, Peter, 1996: ‘“Naughty but nice”: musical comedy and the rhetoric of the girl, 1892-1914’. In: Booth, Michael R & Kaplan, Joel H (eds), 1996: The Edwardian Theatre: Essays on Performance and the Stage. Cambridge University Press: 36-60 Burton, Alan & O’Sullivan, Tim, 2009: The Cinema of Basil Dearden and Michael Relph. Edinburgh University Press Stone, Harry, 2009: The Century of Musical Comedy and Revue. AuthorHouse Irish Film Censors Records: http://www.tcd.ie/irishfilm/censor/show.php?fid=3457

|

|||||

|