|

|

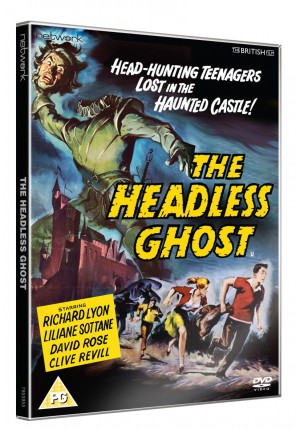

Headless Ghost (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st November 2013). |

|

The Film

The Headless Ghost (Peter Graham Scott, 1959)  In an interview with Tom Weaver, Herman Cohen once suggested, in response to Weaver’s statement that The Headless Ghost is ‘not a funny picture’, that ‘I never liked that picture’ but towards the end of production on The Horrors of the Black Museum, Jim Nicholson asked Cohen if he could ‘knock out a second feature in black and white, just to go with Black Museum, we’ll get the whole program from RKO, from Loew’s, from Texas’ (Cohen, quoted in Weaver, 2003: 68). Cohen responded by suggesting a horror-comedy, which eventually developed into The Headless Ghost, which Cohen co-wrote with Aben Kandel. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Herman Cohen once suggested, in response to Weaver’s statement that The Headless Ghost is ‘not a funny picture’, that ‘I never liked that picture’ but towards the end of production on The Horrors of the Black Museum, Jim Nicholson asked Cohen if he could ‘knock out a second feature in black and white, just to go with Black Museum, we’ll get the whole program from RKO, from Loew’s, from Texas’ (Cohen, quoted in Weaver, 2003: 68). Cohen responded by suggesting a horror-comedy, which eventually developed into The Headless Ghost, which Cohen co-wrote with Aben Kandel.

Kandel and Cohen came up with the film’s basic premise: three vacationing students are taken on a tour of a supposedly haunted castle and decide to hide within its walls in an attempt to get a first-hand experience of the haunting. Setting a comedy-horror picture within a supposedly haunted castle was not particularly original: the Will Hay comedy The Ghosts of St Michaels (Marcel Varnel, 1941) featured a similar castle setting, with Hay playing a teacher in a school whose students are, owing to the outbreak of war, relocated to a castle on the Isle of Skye which is said to be haunted by a phantom piper. In Old Mother Riley’s Ghosts (John Baxter, 1941), Arthur Lucan’s Old Mother Riley discovers that she has inherited a Scottish castle that is reputed to be haunted. Kandel and Cohen’s script contains a major difference from these earlier films: like the majority of Cohen’s other films, The Headless Ghost is a teen-oriented horror picture that features three youthful protagonists – in this case, three university students, two of whom are American (Bill and Ronnie, played be Richard Lyon and David Rose respectively), and one of whom is Danish (Ingrid, played by Liliane Sottane). The focus on university students who investigate a supposedly haunted castle also recalls Mario Bava’s later colour Gothic horror picture, Gli orrori del castello di Norimberga/Baron Blood (1972), in which student Peter Kleist (Antonio Cantafora) returns to his home in Austria and teams up with architecture student Eva Arnold (Elke Sommer) to investigate the malicious spectre of Baron Otto Von Kleist, who is said to haunt the castle that, centuries ago, belonged to Peter’s ancestors.  The film opens aboard a tourist bus where the conductor/tour guide announces, ‘And now, ladies and gentlemen, we’re approaching our destination: Ambrose Castle’. The castle, we are told, has been opened to the public by the sixteenth Earl of Ambrose, and ‘also, if you’re lucky, you may run into one of the ghosts who are supposed to haunt the castle’. The film opens aboard a tourist bus where the conductor/tour guide announces, ‘And now, ladies and gentlemen, we’re approaching our destination: Ambrose Castle’. The castle, we are told, has been opened to the public by the sixteenth Earl of Ambrose, and ‘also, if you’re lucky, you may run into one of the ghosts who are supposed to haunt the castle’.

The bus drives through the countryside, shrouded in mist, and approaches the castle. Ingrid, Bill and Ronnie are introduced. ‘What’s so impressive about a heap of old stones surrounded by a shallow ditch’, one of the Americans notes dryly. The sixteenth Earl of Ambrose shows the tourists around the castle. As he introduces the group to the portraits of his ancestors, including Malcolm, who ‘was beheaded for leading an insurrection against King Henry VII’, the sixteenth Earl of Ambrose asserts that ‘Sometimes I wonder if Malcolm was a true Ambrose. Looks quite wicked, doesn’t he?’ Leading the tourists into the castle’s dungeon, he notes, ‘If these walls could speak, they would perhaps tell you how many men, and how many women, died here’. ‘I do assure you absolutely: there are ghosts in Ambrose Castle’, the Earl assures the three students when they question him over the rumours about the castle. Ingrid reminds her male companions that Shakespeare located Hamlet, and its ghosts, in her home country of Denmark: ‘Here, I can almost feel their [the ghosts’] presence’, she says. This interest piqued, the three students decide to wander off on their own, to see if they can find any evidence of the ghosts. When the bell that indicates the closing of the castle rings, they hide away in the cemetery, avoiding the security guards, so as to spend the night in the supposedly haunted castle.  The students sneak into the main hall. ‘Well, don’t stand there like blithering idiots! Come forward’, a mysterious voice commands. They are afraid and try to flee but find the door locked. The ghost of one of the Earl of Ambrose’s ancestors steps out of his portrait. He sneezes: ‘I do wish they’d dust me. It serves one good to stretch one’s legs. I’ve been in that cramped position for some time’, he tells the bewildered youngsters. He warns them of Malcolm, whose beheading ‘was only the beginning for him [….] He was condemned to wander through Ambrose Castle until his head was reunited with his body’. The students ask why Malcolm’s head cannot be reunited with his body. The ghost says that a living person must recite an incantation whilst throwing a pouch at Malcolm’s portrait: this will release the ‘evil spirit’ that inhabits Malcolm and allow him and the other ghosts to find rest. (‘We can have no rest until he attains it and we return to the family burial ground’.) The students make it their task to quiet the ghost of Malcolm. The students sneak into the main hall. ‘Well, don’t stand there like blithering idiots! Come forward’, a mysterious voice commands. They are afraid and try to flee but find the door locked. The ghost of one of the Earl of Ambrose’s ancestors steps out of his portrait. He sneezes: ‘I do wish they’d dust me. It serves one good to stretch one’s legs. I’ve been in that cramped position for some time’, he tells the bewildered youngsters. He warns them of Malcolm, whose beheading ‘was only the beginning for him [….] He was condemned to wander through Ambrose Castle until his head was reunited with his body’. The students ask why Malcolm’s head cannot be reunited with his body. The ghost says that a living person must recite an incantation whilst throwing a pouch at Malcolm’s portrait: this will release the ‘evil spirit’ that inhabits Malcolm and allow him and the other ghosts to find rest. (‘We can have no rest until he attains it and we return to the family burial ground’.) The students make it their task to quiet the ghost of Malcolm.

The Headless Ghost was shot quickly and cheaply: the reason, Cohen notes, ‘why the running time is so short, like sixty-five minutes’ (Cohen, quoted in Weaver, op cit.: 68). Peter Graham Scott was chosen to direct the film: he was a film editor who aspired to become a director. Cohen ‘needed someone to do a fast job under my guidance’ and selected Scott as the best man for the job (Cohen, quoted in ibid.). The film was rushed into production as The Horrors of the Black Museum was still in post-production, shot in the same studio as Black Museum and reusing some of the same sets, with some location footage shot at a castle which Cohen does not name. However, whereas Black Museum was shot on colour stock, The Headless Ghost was monochrome. Both were shot with anamorphic lenses, although the use of widescreen photography arguably adds very little to The Headless Ghost and the more low-key narrative may have been better supported (visually, that is) through a narrower screen ratio. The original cinema release was cut by the BBFC, although the length and nature of these cuts are unclear. The pressbook, included on this disc as a PDF file, cites the film’s length as 5495 feet (61:03 mins, which in PAL terms is 58:37). This presentation of the film has a running time of 60:30 (including the modern Studiocanal logo which precedes the film and lasts for 20 seconds). This would seem to imply that all, or at least some, of the footage cut from the original UK cinema release has been restored to this presentation of the film.

Video

Shot in Dyaliscope, The Headless Ghost is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, with anamorphic enhancement. The monochrome photography is crisp and well-presented here, although the despite the use of the (French) anamorphic Dyaliscope process and the effective use of wide angle lenses in some sequences, the film’s cinematography is for the most part very ‘flat’ and uninspiring, possibly a product of the rushed production schedule.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track which is without issues. No subtitles are present.

Extras

Extras include an image gallery (0:37) and two pressbooks (stored on the disc as PDF files).

Overall

The Headless Ghost is a mildly entertaining film, although its nature as a low-budget, rushed production is evident throughout the picture. Herman Cohen was reputedly quite unhappy with the film, but it arguably isn’t as bad as it’s often claimed to be. The cast work well together, and the monochrome photography is, in some sequences, very atmospheric. This presentation of the film is good but contains minimal contextual material. Nevertheless, it’s a pretty good presentation of the film: unlike the US disc from VCI (on a double-bill with Horrors of the Black Museum), this release is anamorphic. The Headless Ghost is a mildly entertaining film, although its nature as a low-budget, rushed production is evident throughout the picture. Herman Cohen was reputedly quite unhappy with the film, but it arguably isn’t as bad as it’s often claimed to be. The cast work well together, and the monochrome photography is, in some sequences, very atmospheric. This presentation of the film is good but contains minimal contextual material. Nevertheless, it’s a pretty good presentation of the film: unlike the US disc from VCI (on a double-bill with Horrors of the Black Museum), this release is anamorphic.

References: Weaver, Tom, 2003: Double Feature Creature Attack: A Monster Merger of Two More Volumes of Classic Interviews. London: McFarland For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|