|

|

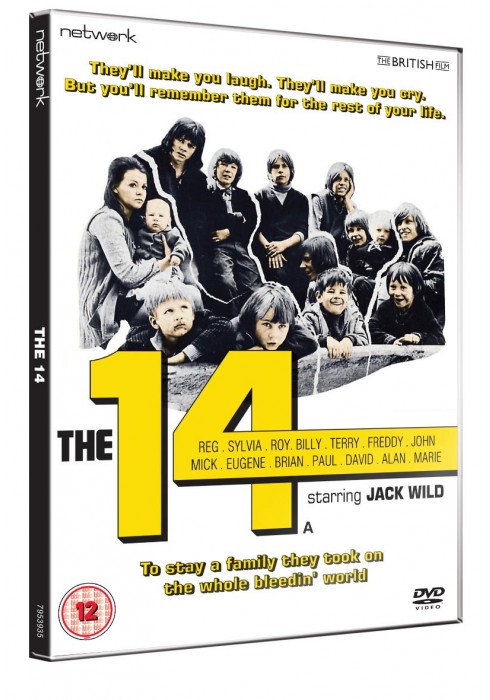

14 (The) AKA Existence AKA The Wild Little Bunch

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd November 2013). |

|

The Film

The 14 (David Hemmings, 1973) The 14 (David Hemmings, 1973)

AKA Existence and The Wild Little Bunch The second film directed by actor David Hemmings, following his 1972 picture Running Scared (sadly apparently MIA on any home video format), The 14 was the winner of the Silver Bear at the 23rd Berlin International Film Festival. Running Scared’s elliptical style seems to have been influenced by filmmakers like Antonioni (in whose Blow-Up Hemmings, of course, turned in one of his most famous performances), and the gritty street-level drama within The 14 seems to owe much to Italian neo-realism and films like De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves (1948) - and, of course, British New Wave films such as Tony Richardson’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1961). Taking place in London, The 14, also released under the titles Existence and The Wild Little Bunch, focuses on a family of youngsters living in a terraced house that is scheduled for demolition, who are forced to fend for themselves after their mother (June Brown) dies suddenly. Following the death of the children’s mother, they are informed by Sanders (John Bailey), a man from Social Services, that they are to be split up. Despite protests from the eldest brother Reg (Jack Wild), who is nearing the age of 18 and hopes to keep the family together with himself as its head, Sanders informs them that there is nothing that can be done, especially as their home is scheduled for demolition. Hemmings says that his ‘film  In his autobiography, Hemmings referred to the film, which was based on a true story, as ‘a wonderful, true and moving story’ that attempted to show what they [the children] went through and the reactions they met with in the adults and officials they encountered’ (Hemmings, 2004: 271). In real life, seven of the children had managed to stay together, being rehomed with a Cornish farmer. However, Hemmings notes that when the farmer’s wife died, the children were once again faced by an uncertain future. In adapting this story for the cinema, the producers committed themselves to establishing ‘a trust fund for the family that would benefit from a proportion of the profits of the film’ (ibid.: 272). Where the family had, in reality, lived in Birmingham, the filmmakers set the story in London, and most of the film was shot in a temporary studio in Willesden, although the picture also makes heavy use of footage shot on location. In his autobiography, Hemmings referred to the film, which was based on a true story, as ‘a wonderful, true and moving story’ that attempted to show what they [the children] went through and the reactions they met with in the adults and officials they encountered’ (Hemmings, 2004: 271). In real life, seven of the children had managed to stay together, being rehomed with a Cornish farmer. However, Hemmings notes that when the farmer’s wife died, the children were once again faced by an uncertain future. In adapting this story for the cinema, the producers committed themselves to establishing ‘a trust fund for the family that would benefit from a proportion of the profits of the film’ (ibid.: 272). Where the family had, in reality, lived in Birmingham, the filmmakers set the story in London, and most of the film was shot in a temporary studio in Willesden, although the picture also makes heavy use of footage shot on location.

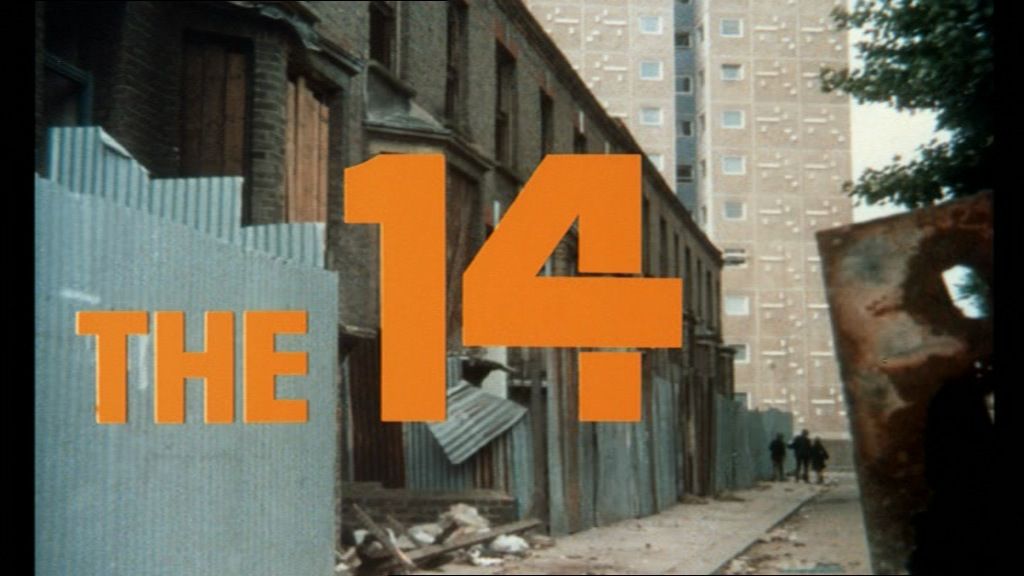

The children and young people are uniformly excellent in their roles, and Hemmings claims that he elicited such strong performances from his young cast by ‘arrang[ing] all sorts of treats and outings for them’, such as ‘boules tournaments on the stage, or I’d take them all go-karting or stock-car racing’ (ibid.). This is something Hemmings claims that he also did for his ‘adult cast and crew, because I found that it gave a greater sense of cohesion and teamwork to the company’ (ibid.). The opening sequence sets the context for the film. Whilst on the soundtrack jaunty music plays, children are shown wandering through the streets, playing on train lines (an index of youthful defiance) and watching as the old Victorian terraces are torn down. They play amongst the rubble and debris of the partially-demolished terraces and vandalized cars. A woman (the children’s mother, listed in the film’s credits simply as ‘The Mother’) enters a terraced house. Cut to inside: it’s dark and gloomy. A baby screams. Her boyfriend Tommy (Alun Armstrong) is asleep in the same room as the child: the baby’s cries do not disturb him. The Mother comforts her youngest child. Soon, the other children return home. The house is filled with commotion; The Mother dishes out the evening meal (soup), telling her eldest son Reg that, ‘I’ve got the pain again [….] Remember what I said’. He reassures her: ‘Don’t worry: nothing’s going to happen’. However, that night The Mother will be rushed to hospital, and the children will soon find themselves without their sole parent.  Over dinner, Reg discusses his ambition to become a lifeguard in Australia. Despite his sister’s assertion that ‘We aren’t going to Australia’, Reg clings to his dream throughout the film, although from time to time his belief in the possibility of his ambition coming true wavers. Immediately after the death of The Mother, Reg arranges the chores with the eldest daughter: ‘next month I’ll be 18, or near as dammit’, he says, and plans to get a job so as to support the other children. He talks about his previous plans to go to Australia, ‘but I think it’d be better if I get a job like me dad’ – a scrap metal man. The camera dollies away from the pair, isolating them as they stand on the landing: their dreams are receding into the distance. Over dinner, Reg discusses his ambition to become a lifeguard in Australia. Despite his sister’s assertion that ‘We aren’t going to Australia’, Reg clings to his dream throughout the film, although from time to time his belief in the possibility of his ambition coming true wavers. Immediately after the death of The Mother, Reg arranges the chores with the eldest daughter: ‘next month I’ll be 18, or near as dammit’, he says, and plans to get a job so as to support the other children. He talks about his previous plans to go to Australia, ‘but I think it’d be better if I get a job like me dad’ – a scrap metal man. The camera dollies away from the pair, isolating them as they stand on the landing: their dreams are receding into the distance.

The children display diversity in their approach to the death of their mother. ‘I reckon that when someone dies, they go where they were happy, only you can’t see ‘em. Mum was happy here, wasn’t she?’, Reg says optimistically. ‘They buried mum’, one of the other boys responds matter-of-factly. When Social Services send a woman to care for the children, she introduces herself to them: ‘You can call me Auntie Rose’. ‘We don’t have no Auntie Rose’, one of the boys says. ‘You do now, lovey’, she responds before setting about cleaning the house and bathing the children. However, it is not long before the children are running rings around her, and they stage a very direct rebellion against their new ‘Auntie Rose’ after they discover that she has moved her things into their mother’s bedroom. Following this, they throw food at her during dinner and chase her from the house. As the narrative progresses, we share the children’s frustration at the way they are treated by the local authority and Hemmings encourages us to empathise with their frustration and their need to antagonize the various figures of authority that are charged with their care: during one sequence, they reduce to tears a nun who has been given the task of caring for them during a group shower. In terms of its depiction of youth, the film is reminiscent of New Wave films such as Truffaut’s Les quatre cents coups/The 400 Blows (1959) and, to some extent, Bunuel’s film about child poverty in Mexico City, Los olvidados/The Young and the Damned (1950). The film is uncut and runs for 101:32 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in what appears to be its original screen ratio of 1.66:1, with anamorphic enhancement. The photography is gritty and grimy, taking place in and amongst the partially demolished Victorian terraces and urban spaces. Visually, the film is somewhat reminiscent of Shirley Baker’s photography of Salford and Manchester, but in colour and based in London. (John Bulmer’s colour documentary photography of the North of England in the 1960s and early 1970s is another strong point of comparison.)

Audio

Audio is presented via a stereo track. This is clean and clear throughout. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes a full-frame, open-matte presentation of the film (101:32) (grabs comparing the compositions in this full-frame version with the widescreen presentation are presented below), the film’s original trailer (3:17) and a stills gallery (0:49). Also included, as DVD-Rom content, is the film’s original pressbook (as a PDF file, 5 pages). The widescreen image is on the left; the grab from the full-frame presentation is on the right.

Overall

Hemmings’ film is a thoroughly engaging picture which doesn’t sop to conventions. In many ways, it’s as challenging as Hemmings’ first film as a director, although whereas that picture showed Hemmings being influenced by the non-linear, internal approach of filmmakers like Antonioni, this film has clear roots in the naturalistic ‘new wave’ cinemas of the 1950s and 1960s. There’s arguably a touch of Pasolini here too: June Brown’s character of the mother, who is not given a name within the film, is frequently framed in painterly compositions alone – either in mid-shot (in which she occupies the centre of the frame) or tight close-ups – and this, combined with the patience displayed by her character from her first appearance to her last, recalls the methods by which Pasolini gives his characters a ‘saintly’ appearance. Hemmings’ film is a thoroughly engaging picture which doesn’t sop to conventions. In many ways, it’s as challenging as Hemmings’ first film as a director, although whereas that picture showed Hemmings being influenced by the non-linear, internal approach of filmmakers like Antonioni, this film has clear roots in the naturalistic ‘new wave’ cinemas of the 1950s and 1960s. There’s arguably a touch of Pasolini here too: June Brown’s character of the mother, who is not given a name within the film, is frequently framed in painterly compositions alone – either in mid-shot (in which she occupies the centre of the frame) or tight close-ups – and this, combined with the patience displayed by her character from her first appearance to her last, recalls the methods by which Pasolini gives his characters a ‘saintly’ appearance.

The film ends with a quote from John Masefield’s poem ‘The Everlasting Mercy’ (‘And he who gives a child a treat, makes joy bells ring in Heaven’s street;/ And he who gives a child a home, build palaces in Kingdom come’), and Hemmings’ approach to his material shows a comprehension of the sights, sounds and emotional texture of the environment of poverty in which the children live. The children are challenging in their behaviour but they are depicted sympathetically; and on the whole, Hemmings does not resort to stereotypes. What results is a complex, challenging film which, thankfully, has been rescued from relative obscurity by Network. This release is highly recommended. References: Hemmings, David, 2004: Blow-Up and Other Exaggerations. London: Robson For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|