|

|

Tokyo Fist AKA Tokyo-ken (Blu-ray)

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Third Window Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd December 2013). |

|

The Film

Tokyo Fist aka Tokyo-ken (Tsukamoto Shinya, 1995)  In his capsule review of Tokyo Fist, Mark Schilling refers to Shinya Tsukamoto as a ‘born film-maker’: when Tsukamoto was no more than nineteen, his short films had been screened at festivals and shown on Japanese television (2010: 53). His first feature, Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) consolidated Tsukamoto’s themes and defined his work for years to come: a cyberpunk fantasy of flesh and machine that was both ‘ultra violent [and] ultra-erotic’, Tetsuo was edited like a fever dream, with Tsukamoto using ‘thousands of cuts flashing by like images out of a bad speed trip’ (ibid.). The film’s narrative was structurally simple (after a traffic accident with a ‘metal fetishist’, a salaryman slowly transforms into a cyborg) but thematically complex. In its focus on scenes of flesh being penetrated by and melding with metal, Tetsuo drew parallels with the ‘body horror’ of David Cronenberg – especially the dark eroticism of Dead Ringers (1988) and the melding of man and machine within Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly (1986). Ultimately, Schilling argues, until Tetsuo ‘[n]o one had distilled the extremes of violence and lust on the screen with such obsessive detail and unbridled directness’ (ibid.). In his capsule review of Tokyo Fist, Mark Schilling refers to Shinya Tsukamoto as a ‘born film-maker’: when Tsukamoto was no more than nineteen, his short films had been screened at festivals and shown on Japanese television (2010: 53). His first feature, Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) consolidated Tsukamoto’s themes and defined his work for years to come: a cyberpunk fantasy of flesh and machine that was both ‘ultra violent [and] ultra-erotic’, Tetsuo was edited like a fever dream, with Tsukamoto using ‘thousands of cuts flashing by like images out of a bad speed trip’ (ibid.). The film’s narrative was structurally simple (after a traffic accident with a ‘metal fetishist’, a salaryman slowly transforms into a cyborg) but thematically complex. In its focus on scenes of flesh being penetrated by and melding with metal, Tetsuo drew parallels with the ‘body horror’ of David Cronenberg – especially the dark eroticism of Dead Ringers (1988) and the melding of man and machine within Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly (1986). Ultimately, Schilling argues, until Tetsuo ‘[n]o one had distilled the extremes of violence and lust on the screen with such obsessive detail and unbridled directness’ (ibid.).

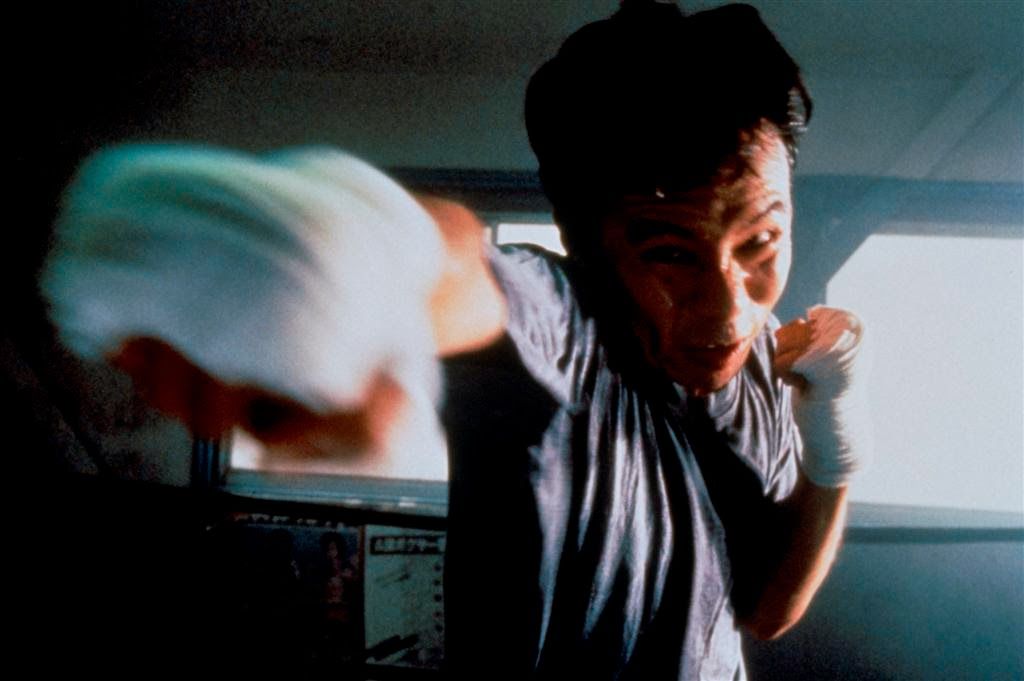

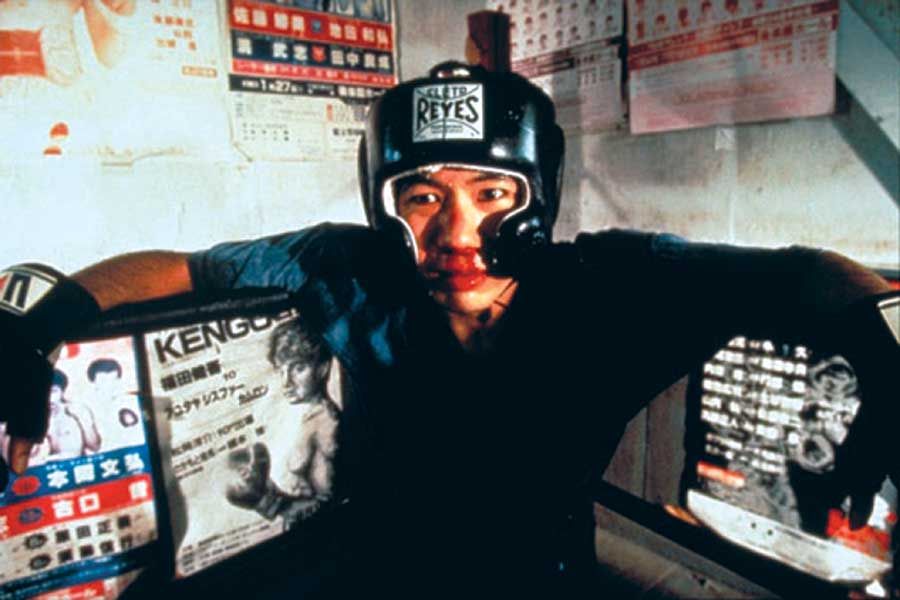

Like Tetsuo, Tokyo Fist has a relatively simple, direct narrative: salaryman Tsuda Yoshiharu (played by Tsukamoto himself) lives a frustrating life. He is bored with his job, and his relationship with his live-in girlfriend Hizuru (Kaori Fujii) is static and uneventful. He also suffers from constant fatigue, for which he seeks medical help. A chance meeting with former schoolmate Kojima Takuji (Kôji Tsukamoto), a semi-professional boxer, throws Tsuda’s life into a state of flux. Kojima invites himself into Tsuda’s home and seduces Hizuru. In retaliation, Tsuda becomes obsessed with boxing, whilst Hizuru moves in with Kojima and begins to practice body piercing on herself. Eventually, Kojima is commissioned to take part in a boxing match with a deadly opponent, and he reveals to Hizuru that as youths, he and Tsuda witnessed the murder of a young girl – a memory that Tsuda seems to have repressed but which may be resurfacing in Tsuda’s fascination with, and capacity for, brutal violence. Lindsay Anne Hallam has discussed the similarities between Tsukamoto’s films and the films of David Cronenberg. Both directors, Hallam argues, explore a theme of ‘latent desires and feelings [that] are manifested physically on the bodies of the characters’ (2011: 104). Tetsuo and its sequel Tetsuo 2: Body Hammer (1992) feature characters whose ‘repressed sexual and violent desires are expressed through the fusion of flesh with metal and other technological materials’: their bodily metamorphoses are accompanied by liberation of their lustful and violent impulses (ibid.). Consequently, Hallam argues, ‘it is through the body that the cycle of transgression begins. Through the violation of the boundaries of the body, in the integration of flesh with metal, the characters are enabled to transgress against, and then destroy, all previous norms of body and society’ (ibid.). However, whereas Cronenberg’s characters in films like Shivers (1975) and Videodrome (1983) view their transformations with both ‘anxiety and disgust’, Tsukamoto’s characters experience ‘joy and delight’ (ibid.). Hallam argues that Tsukamoto’s characters can be compared with Sadean libertines: they ‘use their bodies to rebel against the prevailing culture, and rejoice in the resulting mayhem and the destruction of ordered society’ (op cit.: 105).  Tokyo Fist is filled with images of decay, masochism, body modification, self-mutilation and the restructuring/reworking of the body. In the opening sequence, Tsukamoto shows a mass of men shadow boxing in a gym, underscored with harsh, abrasive industrial music. The editing is frenetic; the tone is combative. In medium shot, Kojima holds our gaze as he directs his blows towards us, and Tsukamoto cuts to a series of stop-motion animation shots of entrails exploding. Shortly afterwards, whilst walking to work Tsuda spots a dead cat in an alleyway, maggots feasting on its insides. He is fascinated by the sight and returns to the scene later, only to discover that the cat has vanished and the only sign of its presence is a stain on the concrete pavement. After discovering Hizuru’s infidelity, Tsuda mutilates himself by repeatedly headbutting a mirror; this is a gesture he repeats towards the end of the film, this time headbutting a concrete post when he is confronted with the memory of the girl whose murder he witnessed as a youth. Tokyo Fist is filled with images of decay, masochism, body modification, self-mutilation and the restructuring/reworking of the body. In the opening sequence, Tsukamoto shows a mass of men shadow boxing in a gym, underscored with harsh, abrasive industrial music. The editing is frenetic; the tone is combative. In medium shot, Kojima holds our gaze as he directs his blows towards us, and Tsukamoto cuts to a series of stop-motion animation shots of entrails exploding. Shortly afterwards, whilst walking to work Tsuda spots a dead cat in an alleyway, maggots feasting on its insides. He is fascinated by the sight and returns to the scene later, only to discover that the cat has vanished and the only sign of its presence is a stain on the concrete pavement. After discovering Hizuru’s infidelity, Tsuda mutilates himself by repeatedly headbutting a mirror; this is a gesture he repeats towards the end of the film, this time headbutting a concrete post when he is confronted with the memory of the girl whose murder he witnessed as a youth.

Tsukamoto seems to suggest that Tsuda’s decision to take up boxing is driven by his desire to model himself after Kojima – who has dealt with his memory of the girl’s death in a different way, by channelling his aggression rather than (like Tsuda) repressing his knowledge of the incident. However, both Tsuda and Kojima seem to take a masochistic delight in their boxing matches. Kojima is reminded by his trainer that he can never be an ‘in fighter’: ‘The only way a coward like him [Kojima] can win is if he mastered mind control’, the trainer says. However, he nevertheless accepts the fight with Kumagaki, who has already killed one opponent, Aoki. Prior to the match, Kojima and Tsuda spar until their faces are swollen and bloody, and during the match Kojima faces Kumagaki in an aggressive bout that will leave Kojima’s face unrecognisable, a swollen mass of sores, blood bursting geyser-like from his cuts. Hizuru is just as complicit in this theme of self-mutilation. After Hizuru has been seduced by Kojima, she gradually becomes fascinated with body art and body piercing. Attempting to alienate herself from her former life, she acquires a tattoo on her upper arm as a means of marking herself as undesirable to Tsuda and his apparently conservative family; later, in sympathy, Tsuda will acquire a similar tattoo. More vividly, in a sequence that is lit red, like a scene from a Mario Bava film, she pierces her own ears; the ritual is shown in full, in unflinching close-up. Later, after she has abandoned Tsuda and moved in with Kojima, she pierces her other ear. ‘What’s it with you?’, Kojima asks, clearly disturbed by her act of body modification. Shortly after, the ritualistic aspect of these scenes is consolidated when Tsukamoto shows Hizuru piercing her nose, with Kojima responding by calling her ‘a freak’; and much later in the film, as Kojima is preparing for his fight with Kumagaki, he has aggressive sex with Hizuru, stripping her and revealing both to him and the audience that Hizuru has pierced her nipples. (‘I’m so scared. Everybody’s gone crazy’, he tells her during this scene.) Kojima pulls at one of the nipple rings with his teeth; Hizuru squirms with a mixture of pain and delight.  The changes to Hizuru’s body (and identity) are a source of anxiety for Tsuda. In one scene, he pleads with Kojima to free Hizuru, as if she were a hostage: ‘Let Hizuru go’, he tells Kojima, ‘I’m scared to see her change’. However, when Tsuda finally manages to confront Hizuru and pleads with her to leave Kojima, she tells him masochistically, ‘I wouldn’t mind even if he beats me to death’. In response, Tsuda – equally masochistically – allows Hizuru to beat him viciously. We see from Tsuda’s point of view as Hizuru pounds his face with her fists. He is left with a swollen, bruised face. The changes to Hizuru’s body (and identity) are a source of anxiety for Tsuda. In one scene, he pleads with Kojima to free Hizuru, as if she were a hostage: ‘Let Hizuru go’, he tells Kojima, ‘I’m scared to see her change’. However, when Tsuda finally manages to confront Hizuru and pleads with her to leave Kojima, she tells him masochistically, ‘I wouldn’t mind even if he beats me to death’. In response, Tsuda – equally masochistically – allows Hizuru to beat him viciously. We see from Tsuda’s point of view as Hizuru pounds his face with her fists. He is left with a swollen, bruised face.

The changes undergone by the characters’ bodies also reflect changes in their identities: after they have been introduced to Kojima’s world, Tsuda and Hizuru take on different identities, both of which are defined by both emotional and physical masochism. At one point, Hizuru asserts that Kojima is turning Tsuda into ‘a monster’ and Kojima will ‘be his [Tsuda’s] first victim’. The theme is introduced early, during one of Kojima’s visits to Tsuda and Hizuru’s flat: Hizuru notes that a boxer’s features can be changed by being struck in the face, effectively changing their identity. Schilling argues that although, in Tokyo Fist, ‘the forces driving the characters [are] elemental’, the characters are more developed than those in Tetsuo (op cit.: 53). For example, Hizuru, who for Schilling is ‘the film’s most intriguing character’, ‘is not a passive pawn in a macho sexual game, but a strong-willed type who, through the tattoo artist’s needle and her own experiments in body piercing, explores the erotic ecstasy of pain’ (ibid.). Additionally, as Tsung-Yi Michelle Huang notes, where the protagonists of the Tetsuo films feature salaryman protagonists who transform themselves through self-mutilation and by penetrating their flesh with metal, Tokyo Fist’s protagonist ‘endeavors to transform himself with blood, perspiration, and pain in the boxing gym’ (2004: 86). However, despite similarly heavy themes Tetsuo was also a blackly comic study in urban alienation: its protagonist wanders through an urban environment from which he is utterly disconnected. A telephone call between the protagonist and his girlfriend consists solely of the pair muttering ‘Hello’ to one another. Tsukamoto himself has commented that his films are dominated by a ‘theme of human body and the city’ (Tsukamoto, quoted in Hallam, op cit.: 105). Tsukamoto’s subsequent films would foreground this disjuncture between the individual and their environment. Like Tetsuo, Tokyo Fist features ‘shots of Tokyo office buildings, high-rises and freeways in all their totalitarian splendour, juxtaposed with shots of factory furnaces, industrial scrap-heaps and dark forests of freeway pylons in all their hellish glory’ (Schilling, op cit.: 53). Tsukamoto’s films feature low-ranking salarymen and women who are confined within cramped living and working spaces. Even outside on the streets, they are overwhelmed by huge, angular buildings which dominate the skyline. Tsung-Yu Michelle Huang suggests that Tsukamoto diminishes his protagonists within his mise-en-scene by juxtaposing them visually with the huge buildings that dominate Tokyo’s skyline: ‘[t]hese shots of the buildings, as a perfectly designed geometrical space, and the stunted human body contained in their fragmentary box within boxes, are some of the most expressive images throughout the film, suggesting the subjugation of the body by the repressive abstract space of Tokyo’ (op cit.: 89). After the opening sequence depicting the boxing gym, Tsuda is introduced as he walks through a sterile office environment, neatly divided up into cubicles that are separated from one another by flimsy walls. Outside the building, in a composition that will be repeated throughout the film, Tsuda walks past huge ultramodern office buildings, all glass and steel; the image is given a cold blue tint that is suggestive of sterility, depersonalisation and stagnation.  Huang suggests that this theme developed within Tsukamoto’s work owing to the fact that Tsukamoto grew up ‘witnessing the urbanization of Tokyo from the 1960s to the construction boom of the 1980s’ (op cit.: 86). Tsukamoto has asserted that ‘I grew up with those buildings. I was small, and the buildings were small at first. Then the buildings became bigger and bigger as I grew up. That strange intimacy with the buildings and the city is analogous to the mixed feelings for the parents: affections and fears are two sides of the same coin’ (Tsukamoto, quoted in ibid.). In the Tetsuo films and Tokyo Fist, Huang argues, the protagonists learn to ‘mimic’ their environment, ‘turn[ing] into killing machine[s] so as to blend in’ (ibid.). Their violence may be interpreted ‘as a reaction to the global city formation’ (ibid.). Tsuda begins the film as an insurance salesman who has a clinical understanding of the concept of ‘risk’ (‘There are so many risks in the business world, and we offer consulting services for all kinds of risks’, he tells a prospective client) but, as the narrative progresses, he develops an increasing awareness of, and fascination towards, real-world risks. Huang suggests that this theme developed within Tsukamoto’s work owing to the fact that Tsukamoto grew up ‘witnessing the urbanization of Tokyo from the 1960s to the construction boom of the 1980s’ (op cit.: 86). Tsukamoto has asserted that ‘I grew up with those buildings. I was small, and the buildings were small at first. Then the buildings became bigger and bigger as I grew up. That strange intimacy with the buildings and the city is analogous to the mixed feelings for the parents: affections and fears are two sides of the same coin’ (Tsukamoto, quoted in ibid.). In the Tetsuo films and Tokyo Fist, Huang argues, the protagonists learn to ‘mimic’ their environment, ‘turn[ing] into killing machine[s] so as to blend in’ (ibid.). Their violence may be interpreted ‘as a reaction to the global city formation’ (ibid.). Tsuda begins the film as an insurance salesman who has a clinical understanding of the concept of ‘risk’ (‘There are so many risks in the business world, and we offer consulting services for all kinds of risks’, he tells a prospective client) but, as the narrative progresses, he develops an increasing awareness of, and fascination towards, real-world risks.

As the film begins, Tsuda is beset with constant fatigue: he seeks medical treatment for this but discovers that the medical professionals are unable to identify the source of this fatigue. Huang suggests that Tsuda’s fatigue is ‘a symptom of a body drained by the duties of a model citizen’ (op cit.: 89). As he becomes increasingly enmeshed in a world of violence, Tsuda becomes more energised: his fatigue slips away, and both his actions and his language become more aggressive (‘I’ll even beat the shit out of the people you know until you die’, Tsuda threatens Kojima at one point). The film constantly returns to the primal scene, the murder of the young girl, that links Tsuda and Kojima: it is a moment of trauma that is central to the identities of the two men, and which links them intimately. Tsukamoto foregrounds this potentially homoerotic aspect of Tsuda and Kojima’s relationship: at one point, Hizuru asks Kojima, ‘What’s on your mind, your fight or Tsuda? Are you gay?’ (‘I just wanted to see his face crushed like…’ Kojima responds before trailing off and telling Hizuru of the murder he and Tsuda witnessed as youths, concluding that after he took up boxing to channel his feelings of frustration, ‘Tsuda became a nobody [….] But his face now reminds me of the face then, looking like a monster’.) With hindsight, it is easy to see that there are some strong links between Tokyo Fist and Chuck Palahniuk’s era-defining novel of masculine angst (and repressed homosexuality) Fight Club. In both Tokyo Fist and Fight Club, controlled aggression is used both as a metaphor for urban/capitalist alienation, and as a means of combating that alienation. Both texts focus heavily on themes of identity: in Palahniuk’s novel, the relationship between the unnamed narrator (known only as ‘Narrator’) and Tyler Durden is revealed to be searingly intimate (Durden is exposed to be a repressed aspect of the Narrator’s personality), and in Tokyo Fist Tsuda and Kojima’s identities become increasingly intertwined. (This is an aspect of the film emphasised by Tsukamoto’s casting of himself as Tsuda, and his brother Kôji Tsukamoto as Kojima.) Additionally, both the Narrator in Palahniuk’s novel and Tsuda in Tokyo Fist are salaryman characters who suffer from sleep-related disorders that seem to be a symptom of their alienation and frustration with their roles in society: where Tsuda in Tokyo Fist suffers from constant fatigue, the Narrator in Fight Club experiences a perpetual state of insomnia. Finally, both Palahniuk’s novel and Tsukamoto’s film suggest the impossibility of conceptualising ‘risk’ or generating a true sense of self-awareness without experiencing violence and aggression: at one point in Fight Club, Durden asks the Narrator, ‘How much can you know about yourself if you've never been in a fight?’ This line, like several others in Palahniuk’s novel, would be right at home in Tsukamoto’s Tokyo Fist. The film is uncut and runs for 87:35 mins.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is natural and filmlike. The vivid palette (with strong use of green, red and blue light) is represented very well on this Blu-ray. In all, this is a very pleasing presentation of the film.

NB Images in this review are for illustration purposes only and have no bearing on the presentation of the film contained on Third Window’s Blu-ray release..

Audio

The disc contains a DTS-HD Master Audio two-channel stereo track (in Japanese, naturally) with optional English subtitles. The stereo track is rich and clear throughout, with some punchy (pardon the pun) effects.

Extras

Extras include: - the film’s original Japanese trailer (SD) - the film’s UK trailer (HD, 2:30) - a music video (HD, 4:12) - a three-part interview with Shinya Tsukamoto: -- ‘About Tokyo Fist’ (HD, 18:09). Tsukamoto discusses his inspirations in making the film. He says that on his visits to various festivals after making Tetsuo, he was told by critics that his films were about the relationships between people and the city of Tokyo; he decided to make a film focusing in detail on this relationship. The film was also informed by his brother’s experiences of the boxing world. He also discusses his decision to cast his brother as Kojima: he considered giving the roles to professional actors but decided that in order to be convincing as boxers, he would need to find an actor who could also box – and hence settled on his brother, who had ‘the real skills and body structure’. Shinya also trained as a boxer for a year so had some understanding of boxing. Tsukamoto claims that he wrote the film ‘instinctively’ rather than logically and wanted the audience to react to the film ‘on a gut level’. He discusses the film’s representation of women, and Hizuru’s decision to go to Kojima so she may experience ‘pleasures and pain’. He also talks about Hizuru’s increasing fascination with body art and body modification. He claims Hizuru ‘is the first strong woman’ he created for a film. He says that Tsuda chooses a job as an insurance salesman as it promotes ‘safety and life rather than death’, as a response to the murder he witnessed as a youth. -- ‘About Tokyo Fist and Bullet Ballet’ (HD, 3:22). Tsukamoto talks about the similarities between these two films. -- ‘General Thoughts’ (HD, 4:18). Tsukamoto talks about the differences between film and digital. ‘As a director, it’s more about what you do’, he says: ‘My films are based upon what I want to do. I love film’. However, ‘due to budget and convenience’ he’s ‘been shooting digitally’ in recent years. Digital technology allows him to shoot more takes, and lighting and postproduction are also cheaper and easier with digital shoots – ‘but I still love looking at and touching film’.

Overall

Tokyo Fist is a superb, visceral and thought-provoking film from Shinya Tsukamoto. Third Window’s presentation of the film is excellent and contains some superb contextual material. This release is highly recommended. References: Hallam, Lindsay Anne, 2011: Screening the Marquis the Sade: Pleasure, Pain and the Transgressive Body in Film. London: McFarland Huang, Tsung-Yi Michelle, 2004: Walking Between Slums and Skyscrapers: Illusions of Open Space in Hong Kong, Tokyo and Shanghai. Hong Kong University Press Schilling, Mark, 2010: ‘Tokyo Fist (capsule review)’. In: Berra, John (ed), 2010: Directory of World Cinema: Japan. London: Intellect Books: 53-4 This review has been kindly sponsored by Third Window Films.

|

|||||

|