|

|

Heaven's Gate AKA Johnson County Wars (Blu-ray)

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Second Sight Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th December 2013). |

|

The Film

Heaven’s Gate (Michael Cimino, 1980)  A huge, sprawling film, Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) is usually cited as the film that almost sank Hollywood: along with another big commercial ‘flop’, Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart (1982), it signalled the end of the Hollywood Renaissance/Hollywood New Wave era in which directors had earned increased autonomy and respect. In subsequent years, control would be wrestled from ‘star’ directors like Cimino and Coppola (and contemporaries such as William Friedkin), and the ‘blockbuster’ ethos, gradually ushered in after the twin successes of Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) and Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977), would come to dominate the Hollywood landscape: throughout the 1980s Hollywood films would increasingly become focused on escapist plots, and would be created to maximise profits. A huge, sprawling film, Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) is usually cited as the film that almost sank Hollywood: along with another big commercial ‘flop’, Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart (1982), it signalled the end of the Hollywood Renaissance/Hollywood New Wave era in which directors had earned increased autonomy and respect. In subsequent years, control would be wrestled from ‘star’ directors like Cimino and Coppola (and contemporaries such as William Friedkin), and the ‘blockbuster’ ethos, gradually ushered in after the twin successes of Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) and Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977), would come to dominate the Hollywood landscape: throughout the 1980s Hollywood films would increasingly become focused on escapist plots, and would be created to maximise profits.

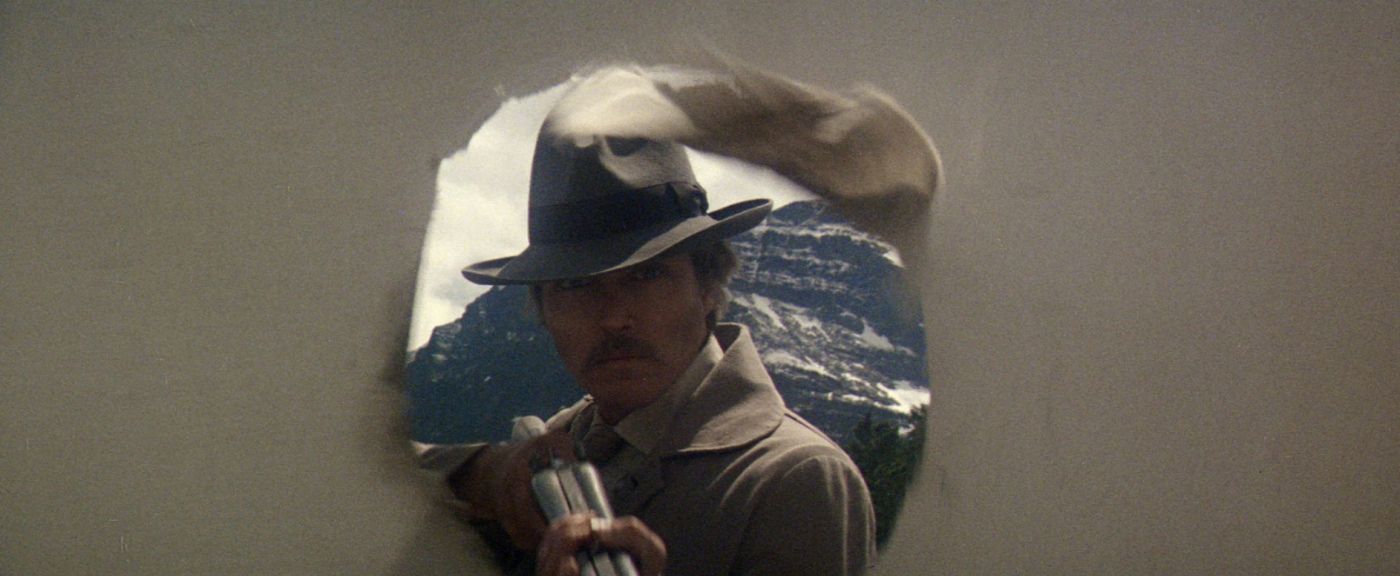

Where Coppola’s One From the Heart was financed by Coppola himself (through American Zoetrope), Heaven’s Gate effectively destroyed United Artists, the studio which had been established in 1919 by Charlie Chaplin, D W Griffith, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks: originally budgeted at $7.5 million, during production the budget spiralled and the film ultimately cost $44 million. In the US, it earned back less than $4 million. Subsequently, United Artists was sold (by its then-owner Transamerica Corporation) to MGM, where it would become little more than a subsidiary. United Artists had begun its life as a distribution company for pictures that had been produced independently by ‘actors, directors and producers who were constitutionally opposed to the studio system and who risked their own money on custom-made pictures that reflected their special talents’ (Balio, 1975: xi). The demise of United Artists, or rather its absorption into MGM, seemed to signal an end to the freedom that had been enjoyed by some filmmakers working on the fringes of Hollywood and heralded the consolidation of the corporate mentality within Hollywood. Prior to Heaven’s Gate, Cimino had been a rising star in the film industry: his earlier films Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974) and The Deer Hunter (1978) had earned critical acclaim, with the latter film winning five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. There was a gradual progression in scope: where Thunderbolt and Lightfoot had been a fairly intimate crime picture, The Deer Hunter was a bold examination of the impact of the Vietnam war. Heaven’s Gate was an even more ambitious picture which revolved around the Johnson County range war of 1892. This progression in terms of scope and scale was matched by the length of the films: where Thunderbolt and Lightfoot was under two hours in length, The Deer Hunter was three hours long. Cimino’s cut of Heaven’s Gate ran to 219 minutes – with a workprint that reputedly ran for five and a half hours. After the film had been shown to the press, to a largely negative response, in mid-November of 1980 United Artists cancelled the general release of the picture, which had been scheduled for the 21st of November. At the behest of Cimino, the film was drastically re-edited and United Artists released a 149 minute version in 1981 (see Balio, 2009: 341). In his second book about United Artists (United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, 2009), Tino Balio suggests that ‘Heaven’s Gate was booby-trapped from the start’ (340). As Steven Bach notes in his book Final Cut: Art, Money and Ego in the Making of ‘Heaven’s Gate’, the Film That Sank United Artists (1999), in the first six days of shooting the production had used 60,000 feet of film, at a cost of approximately $90,000, with the result of only a minute and a half of usable footage. Within two weeks of production starting, the film had incredibly already fallen two weeks behind schedule, and after twenty weeks in production Cimino ‘held a champagne party to celebrate the shooting of the millionth foot of film’ (ibid.). At this stage, United Artists took the drastic action of wrestling away the financial control of the film’s production but stopped short of firing Cimino: Balio quotes an unnamed executive, who noted that had UA taken the decision to remove Cimino from the picture, ‘It would have created a crisis of confidence in a company which had built its reputation on giving directors the right to work without intervention’ (ibid.). As Balio notes, even after its completion UA showed little faith in the film, and this contributed to the film’s lack of success: Pauline Kael noted that ‘if the company thought that the critics were wrong, they would have put millions in advertising and they might have recouped on the picture. A lot of terrible movies get by if the companies believe in them. Bit [UA] didn’t believe in [Heaven’s Gate] and that is why they listened to the press’ (Kael, quoted in ibid.: 341). After Heaven’s Gate, Cimino would struggle to find work. The four feature films he directed after Heaven’s Gate (The Year of the Dragon in 1985; The Sicilian in 1987; a remake of The Desperate Hours in 1990; and finally, The Sunchaser in 1996) were all crime pictures that showed a diminishing sense of scope and impact. The Year of the Dragon, scripted by Oliver Stone, was a fairly ambitious picture that attracted controversy for its supposedly sympathetic depiction of its protagonist’s (Mickey Rourke) racist attitudes, directed towards Chinese Americans and framed as a consequence of his experiences during the Vietnam war. The Sicilian, an adaptation of Mario Puzo’s novel, was equally poorly-received, with the American release cut by around thirty minutes. The Desperate Hours and The Sunchaser, both relatively constrained and conservative films, which Neil Jackson (2002) has commented ‘demonstrate a marked loss of confidence’ when compared with the ‘flamboyance of [Cimino’s] earlier work’ (84). As the title card declares, the film opens in ‘Harvard College, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1870’. An elaborate graduation ceremony is taking place, presided over by the Reverend Doctor (Joseph Cotten). The sequence introduces the friendship between the fiery James Averill (Kris Kristofferson) and the students’ orator William C Irvine (John Hurt). Irvine’s speech subtly mocks the pomposity of the ceremony; he does this by turning the tools of the ceremony (oratory, rhetoric) against itself. The undercurrents within this ostensibly civilised ceremony gradually reveal themselves as, when day begins to turn to night, the men become increasingly drunk, ogle the women and, ultimately, violence breaks out. Cimino cuts from here to ‘Wyoming, Twenty Years Later’ (as another title card asserts). Averill arrives, via a train packed with immigrant farmers, in the town of Sweetwater. On his arrival, he sees the violence meted out against the immigrants, interrupting one particularly brutal beating of an immigrant in front of his family. After learning from Cully (Richard Masur), an acquaintance who is an employee of the railroad company, that the Wyoming Stock Growers Association has hired thugs to intimidate the immigrant farmers, who the Association claims have been stealing cattle, Averill leaves for the home of Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert), with whom Averill appears to be in love. Watson is the madame of a brothel outside Sweetwater, and she is also pursued by one of her ‘regulars’, Nathaniel ‘Nate’ Champion (Christopher Walken) – one of the hands that have been hired by the Association to deal with the immigrant farmers. Frank Canton (Sam Waterson), the head of the Association, reveals that the Association has hired fifty men to hunt down 125 immigrant farmers whose names have been placed on a ‘death list’. The Association will pay these hired guns five dollars a day, with a fifty dollar bonus ‘for every cattle thief shot or hung’. Canton claims that the men and women on the list have in some way been involved in the theft of cattle. Irvine, who is also part of the Association, protests this, arguing that the immigrants’ ‘only stock-in-trade is having large numbers of ragged kids’. However, it seems that the Associations planned genocide of the immigrant settlers has been sanctioned by both the government and the President himself. Averill discovers the existence of this ‘death list’, and it is also revealed that Ella is one of the people who have been marked for execution by the Association’s hired guns. The reveal of this leads to Champion, who is in love with Ella, to question the organisation that has employed him. Disappointed with Ella’s refusal to leave Sweetwater, which is her home, Averill struggles to relay this information to the immigrants, using the communal hall (named ‘Heaven’s Gate’) that is owned by his friend, the entrepreneur John Bridges (Jeff Bridges). The stage is set for a highly unequal confrontation between the immigrants and the Association. Cimino and Francis Ford Coppola are often discussed together: both filmmakers have become associated with the form of historical melodrama. Naomi Greene has compared the work of both filmmakers with Verdi’s operas Rigoletto, I Lombardi and Don Carlos, where ‘history sets the scene for the portrayal of Romantic passions and conventions: heroes are torn by conflicting loyalties, crushed by Destiny, tangled in tragic conflicts which can end only in murder or self-destruction (Greene, 1991: 389). Greene also suggests a more immediate point of reference for both filmmakers may be ‘Italian directors such as Visconti, or the Bertolucci of 1900’ (ibid.: 390). For Greene, both Coppola and Cimino explore historical events as a means of ‘transmuting’ history into myth, taking real historical circumstances and using them to explore ‘general comments involving human destiny, good and evil, the tragedy of power’ (ibid.).  As Greene reminds us, Cimino’s films – and in particular Heaven’s Gate – are highly theatrical. The first killing in Heaven’s Gate, committed by Christopher Walken’s character Nate against an immigrant farmer who we may assume has stolen the cow he is shown butchering, has a highly theatrical dimension. The scene marks the introduction of Nate. The setup to the scene begins with a dolly in to the makeshift home of the immigrant family as the father butchers a carcass. The family slip in the blood of the beast as they drag the carcass away. The father is shown behind a sheet which is hanging on a line. A figure approaches, silhouetted against the other side of the hanging sheet; a shotgun blast rings out, and the father falls dead. Cimino cuts to a medium shot of Walken, still holding the shotgun, framed through the hole his weapon has blown in the sheet. He turns and walks away, leaving the scene of the murder/execution. As Greene notes, this ‘first murder […] is seen through a carefully composed hole in the tent [sic] which both frames it and suggests many of the other frames (archways, doorways) used within the film’ (ibid.). As Greene reminds us, Cimino’s films – and in particular Heaven’s Gate – are highly theatrical. The first killing in Heaven’s Gate, committed by Christopher Walken’s character Nate against an immigrant farmer who we may assume has stolen the cow he is shown butchering, has a highly theatrical dimension. The scene marks the introduction of Nate. The setup to the scene begins with a dolly in to the makeshift home of the immigrant family as the father butchers a carcass. The family slip in the blood of the beast as they drag the carcass away. The father is shown behind a sheet which is hanging on a line. A figure approaches, silhouetted against the other side of the hanging sheet; a shotgun blast rings out, and the father falls dead. Cimino cuts to a medium shot of Walken, still holding the shotgun, framed through the hole his weapon has blown in the sheet. He turns and walks away, leaving the scene of the murder/execution. As Greene notes, this ‘first murder […] is seen through a carefully composed hole in the tent [sic] which both frames it and suggests many of the other frames (archways, doorways) used within the film’ (ibid.).

As Greene also notes, the film’s exploration of the Johnson County range wars reverberates with ‘references to the war in Southeast Asia’, offering an ‘indictment of United States policy [that is] perhaps the strongest ever seen in mainstream film’ (ibid.: 394). The film has a dominant theme of ‘class exploitation’, focusing as it does on ‘the massacre of homesteading immigrants, who embody a peaceful force in most Westerns, at the hands of rich cattle barons and their mercenary killers who are aided not only by the US Army […] but by the President himself’ (ibid.). Where Bertolucci’s 1900 offered a representation of ‘solidarity and hope for the future’ through a similar narrative, Heaven’s Gate depicts the ultimate dominance of the values that the Association stand for: by the end of the film, the immigrants have been massacred and, in the film’s coda, Kristofferson’s James is depicted as having ‘sold out’ to the very system against which he fought, returning to his sweetheart from his university days and spending his final days aboard a luxurious yacht. Yet regret is etched across his aged face (ibid.). Consequently, Greene argues Heaven’s Gate’s ‘pessimism becomes almost unbearable’: the film’s ‘beaten and lonely hero […] is thrice destroyed’: the immigrants he has been helping are massacred; Ella is killed by the Association; ‘and even the personal integrity granted the Western hero is denied him for, at the end, he is a drained shell of a man, drifting aimlessly aboard his yacht off Newport Beach’ (ibid.). Additionally, ‘the ties of friendship’ which were a central element in both Thunderbolt and Lightfoot and The Deerhunter are, in Heaven’s Gate, destroyed: James is alienated from both his friends and his true love by ‘political differences and sexual rivalry’ (ibid.). The film is ultimately about isolation and the failure of resistance; as Greene argues, the ‘film’s rhythm is one of inevitable decline’ (ibid.). The prologue, which takes place at Harvard, 1870, outlines the relationship between Averill and Irvine, and also introduces the sweetheart that Averill will return to in the film’s epilogue, after the death of his true love Ella. Both the prologue and epilogue were added by Cimino, who rewrote his script at the behest of United Artists: Stephen Prince has argued that these two extended sequences ‘made the film seem less like a Western (to the delight of UA executives) and more like the ambitious, arty picture they wanted’ (2002: 34-5). The prologue is interesting inasmuch as it subtly hints at the undercurrents of violence within the wealthy, educated and ‘civilised’ graduates. The speech by Joseph Cotten’s Reverend Doctor quotes an actual speech delivered at a graduation ceremony at Harvard in 1874. Cotten reminds the graduating students that ‘if it be not a mere farce that you are enacting in these sacred valedictory rites; if you mean them and feel them, as I know you do, — they have for you a mandate of imperative duty’. He tells the young men that ‘It’s not great wealth alone that builds the library, found the college, that is to diffuse a higher learning and culture among a people. It is the contact of the cultivated mind with the uncultivated. If it be true that the constitution of American society is peculiarly hostile now to all habits of thought and meditation, it double behoves us […] to look well to the influence we may exert: a high ideal, the education of a nation’. Cotten’s well-meaning sermon is mocked by the students for its po-faced delivery. The young men heckle him, and when Irvine is introduced to deliver his speech to his contemporaries, he subtly mocks the pomp of the ceremony by using the same rhetoric as Cotten, winning the approval of his peers and earning sour glances from the staff.  Shortly after, the ‘high ideals’ of these powerful men are revealed: Averill has returned to Sweetwater transporting a woman who is to be hanged for the murder of her husband. ‘So they’re hanging women now, are they?’, Cully asks him dryly before telling Averill that when a ‘citizen’ buys land in Sweetwater, ‘the rich fellas blackball him […] run him off or kill him [….] I tell you something, if the rich could hire others to do their dying for them, the poor could make a wonderful living’. Shortly after, the ‘high ideals’ of these powerful men are revealed: Averill has returned to Sweetwater transporting a woman who is to be hanged for the murder of her husband. ‘So they’re hanging women now, are they?’, Cully asks him dryly before telling Averill that when a ‘citizen’ buys land in Sweetwater, ‘the rich fellas blackball him […] run him off or kill him [….] I tell you something, if the rich could hire others to do their dying for them, the poor could make a wonderful living’.

Meanwhile, Canton uses rhetoric to justify the Association’s genocide of the immigrant farmers, framing the immigrants as ‘thieves and anarchists’: addressing the other members of the Association, including a disbelieving Irvine, Canton asserts that ‘These immigrants only pretend to be farmers, but we know man of them personally to be thieves and anarchists, openly preying on our ranges’. Leaving Canton’s speech in disgust, Irvine wanders upstairs, where he finds Averill alone, playing pool. Averill, it seems, is able to wander between these very different worlds (the wealthy members of the Association; the poor group of immigrant farmers) at will, although he does not seem fully at home with either group. When Averill moves downstairs to confront Canton, Canton tells Averill that ‘You offset every effort we make to protect our own property and that of members of your own class’. In response, Averill asserts that ‘You’re not my class, Canton, and you never will be. You’d have to die first and be reborn again’. This marks the end of Averill’s association with his former contemporaries, as he allies himself completely with the immigrant farmers. However, in the coda, his presence aboard the yacht and his company with his sweetheart from his days at Harvard suggest that Averill has ‘sold out’ and sacrificed his values and beliefs for security; but his face betrays his ennui and sense of loss. This development is foreshadowed in some of the dialogue. At one point, Irvine asks Averill, ‘James, do you remember the good, gone days’; Averill responds, ‘Clearer and better, every day I get older’. Interestingly, the coda aboard the yacht was added at the behest of United Artists: Cimino’s original script ended with the death of Averill in defense of Ella and Bridges. Averill’s survival of the range war arguably paves the way for a more bitter, defeatist resolution. This presentation of Heaven’s Gate is based on Cimino’s ‘Director’s Cut’, constructed in 2012 and previously released on Blu-ray by Criterion in the States and Carlotta Films in France. This is based on the 219 minute cut shown at those early screenings of the film and released on home video and DVD (the 149 minute cut has never appeared on home video), but with some subtle changes: Cimino has shortened some shots and cut one line of dialogue, as well as eliminating the intermission. It is also worth noting that this UK release has been cut by 59 seconds by the BBFC. The mistreatment of animals during the production of the film has been well-documented (cattle, chickens and horses were reputedly maltreated quite severely on set, with one pony being accidentally killed when a stunt involving an explosion went wrong). The BBFC have demanded cuts ‘to remove scenes of unsimulated animal cruelty orchestrated by the film makers’: a cockfight, orchestrated by Bridges, has been trimmed, as have several scenes depicting the use of tripwires to trip horses (during the during the climax). This presentation of the film thus runs for 216:18 minutes.

Video

This is the same presentation of the film that was released by Criterion in America, and by Carlotta Films in France. The film is presented in its theatrical aspect ratio of 2.40:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. For this new ‘Director’s Cut’, Cimino revised the aesthetic of the film: where earlier releases of the picture had been dominated by browns and yellows (giving the subtle impression of a vintage sepia-toned photograph), Cimino chose to present this version of the film through a more natural colour scheme. See below for comparative screen grabs: images from an earlier DVD release are on the left hand side; images from this new presentation are on the right.

This is a very pleasing presentation of the film. It’s natural and filmlike, with plenty of detail present, and dominated by earthy hues (browns and greens). The original photography (like a good number of other films shot by Vilmos Zsigmond) was dominated by a hazy, soft-focus approach, and this is represented very well on this Blu-ray: aside from Cimino's decision to revised areas of bias within the palette, the presentation - in terms of texture, contrast and density - is true to the film’s original photography, although it’s arguably antithetical to hegemonic ideas about what makes a ‘good’ HD presentation (sharp focus, vibrant colours, etc) owing to decisions made during the production of the film.

Audio

There are two audio options: a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track and a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. The stereo track is the more natural sounding of the two, although the new 5.1 mix works very nicely and is true to the original sound design, only with more immersive surround sound effects. Both tracks feature a naturalistic sound mix, with lines of dialogue often buried in ambient sounds – much like the sound design on some of Robert Altman’s films (M*A*S*H, 1968; McCabe and Mrs Miller, 1971). I’m an audio purist, but must admit that the 5.1 mix offers a rich, deep and immersive experience. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Included on a separate DVD from the main feature, this release contains some excellent contextual material: - ‘True Gate: An Interview with Jeff Bridges’ (19:32), a 20 minute interview with Bridges about his involvement in the film. - ‘Painting Jackson County: An Interview with Vilmos Zsigmond’ (17:59), an illuminating interview with Zsigmond about the shooting of the picture. - the superb 2004 documentary ‘Final Cut: The Making and Unmaking of Heaven's Gate’ (55:09), which covers all aspects of the production and reception of the film. However, labeled as a ‘DVD Release Version’, this is sadly an edited presentation of this documentary, presumably cut down to avoid issues with copyright.

Overall

Heaven’s Gate is a fascinating film. The unusual circumstances of its production and the lack of faith showed in it by United Artists served to hamstring its reputation for many years. However, as Neil Jackson argues ‘[h]indsight and retrospect reveal the film as one of the best of its kind’: a film that ‘infuses the Western with layers of political and social detail’ (op cit.: 84). However, as Jackson admits, the major objection to the film is the lack of a ‘clearly defined narrative’; nevertheless, the various strands of the film are linked by Cimino’s focus on ‘the ceremonial and ritualised aspects of his story’ - the Harvard graduation ceremony that opens the film, the various dancing sequences, and finally the Association’s massacre of the immigrants (ibid.). Likewise, Austin Fisher compares the film with the westerns all’italiana/Italian Westerns produced in the 1960s and 1970s, noting that Heaven’s Gate ‘was […] the culmination of a significant countercultural trend within the Hollywood Western’ of the 1970s, in its depiction of the ‘mechanisms of government and corporate power as murderous, corrupt cabals’ (2011: 182). In many ways the film is a superb, deeply subversive, film that has resonance for today. As Bridges notes at one point in the picture, ‘Goddamin, it’s getting dangerous to be poor in this country, isn’t it?’, to which Averill replies, ‘It always was’. References: Balio, Tino, 1975: ‘Preface’. Balio, Tino, 2009: United Artists: The Company Built By the Stars. University of Wisconsin Press Balio, Tino, 2009: United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press Fisher, Austin, 2011: Radical Frontiers in the Spaghetti Western: Politics, Violence and Popular Italian Cinema. London: I B Tauris Greene, Naomi, 1991: ‘Coppola, Cimino: The Operatics of History’. In: Landy, Marcia (ed), 1991: Imitations of Life: A Reader on Film and Television Melodrama. Wayne State University Press: 388-97 Jackson, Neil, 2002: ‘Michael Cimino’. In: Allon, Yoram et al (eds), 2002: Contemporary North American Film Directors. London: Wallflower Press (Third Edition): 83-4 Prince, Stephen, 2002: A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electric Rainbow, 1980-1989. University of California Press

|

|||||

|