|

|

Bullet Ballet

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Third Window Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th January 2014). |

|

The Film

Bullet Ballet (Shinya Tsukamoto, 1998)  Shinya Tsukamoto’s work is filled with wild imagery that fetishises technology (or rather, the relationships between technology and flesh), which have often led to parallels being drawn between Tsukamoto’s films and the work of the Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg. Tsukamoto’s first feature, Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) consolidated Tsukamoto’s themes and defined his work for years to come: a cyberpunk fantasy of flesh and machine that was both ‘ultra violent [and] ultra-erotic’, Tetsuo was edited like a fever dream, with Tsukamoto using ‘thousands of cuts flashing by like images out of a bad speed trip’ (Schilling, 2010: 53). The film’s narrative was structurally simple (after a traffic accident with a ‘metal fetishist’, a salaryman slowly transforms into a cyborg) but thematically complex. In its focus on scenes of flesh being penetrated by and melding with metal, Tetsuo drew parallels with the ‘body horror’ of David Cronenberg – especially the dark eroticism of Dead Ringers (1988) and the melding of man and machine within Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly (1986). Ultimately, Mark Schilling argues, until Tetsuo ‘[n]o one had distilled the extremes of violence and lust on the screen with such obsessive detail and unbridled directness’ (ibid.). Shinya Tsukamoto’s work is filled with wild imagery that fetishises technology (or rather, the relationships between technology and flesh), which have often led to parallels being drawn between Tsukamoto’s films and the work of the Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg. Tsukamoto’s first feature, Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) consolidated Tsukamoto’s themes and defined his work for years to come: a cyberpunk fantasy of flesh and machine that was both ‘ultra violent [and] ultra-erotic’, Tetsuo was edited like a fever dream, with Tsukamoto using ‘thousands of cuts flashing by like images out of a bad speed trip’ (Schilling, 2010: 53). The film’s narrative was structurally simple (after a traffic accident with a ‘metal fetishist’, a salaryman slowly transforms into a cyborg) but thematically complex. In its focus on scenes of flesh being penetrated by and melding with metal, Tetsuo drew parallels with the ‘body horror’ of David Cronenberg – especially the dark eroticism of Dead Ringers (1988) and the melding of man and machine within Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly (1986). Ultimately, Mark Schilling argues, until Tetsuo ‘[n]o one had distilled the extremes of violence and lust on the screen with such obsessive detail and unbridled directness’ (ibid.).

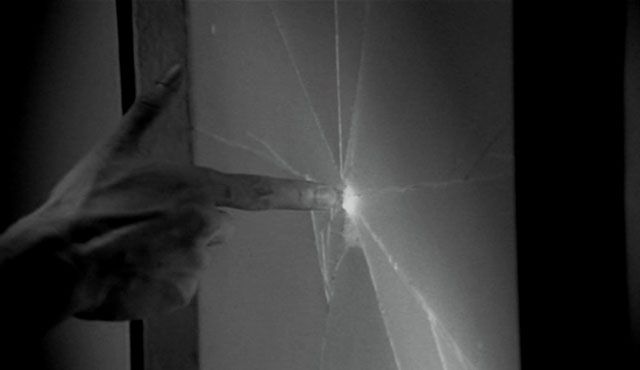

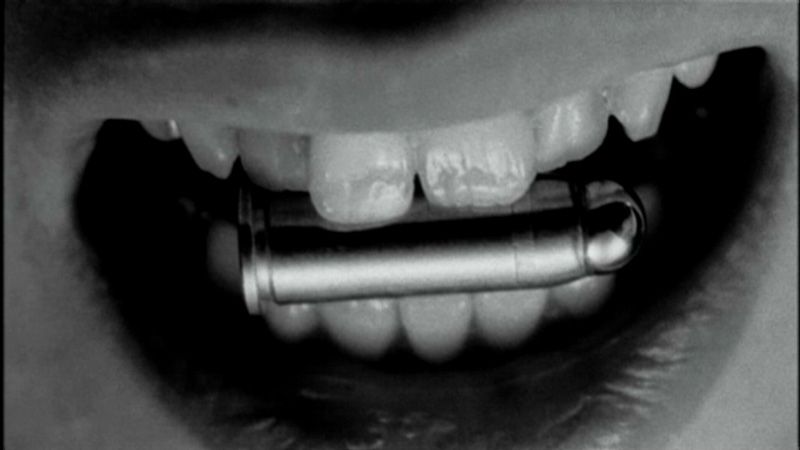

Lindsay Anne Hallam has discussed the similarities between Tsukamoto’s films and the films of David Cronenberg. Both directors, Hallam argues, explore a theme of ‘latent desires and feelings [that] are manifested physically on the bodies of the characters’ (2011: 104). Tetsuo and its sequel Tetsuo 2: Body Hammer (1992) feature characters whose ‘repressed sexual and violent desires are expressed through the fusion of flesh with metal and other technological materials’: their bodily metamorphoses are accompanied by liberation of their lustful and violent impulses (ibid.). Consequently, Hallam argues, ‘it is through the body that the cycle of transgression begins. Through the violation of the boundaries of the body, in the integration of flesh with metal, the characters are enabled to transgress against, and then destroy, all previous norms of body and society’ (ibid.). However, whereas Cronenberg’s characters in films like Shivers (1975) and Videodrome (1983) view their transformations with both ‘anxiety and disgust’, Tsukamoto’s characters experience ‘joy and delight’ (ibid.). Hallam argues that Tsukamoto’s characters can be compared with Sadean libertines: they ‘use their bodies to rebel against the prevailing culture, and rejoice in the resulting mayhem and the destruction of ordered society’ (ibid.: 105). In his 1998 film Bullet Ballet, Tsukamoto turned his attention to a subgenre that has been explored in numerous Hollywood films, especially of the 1970s: the urban vigilante drama. Like Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1974), Bullet Ballet features a protagonist who gradually becomes obsessed with the symbol of the handgun: think of Charles Bronson’s transformation from a conscientious objector to a man who, in the film’s closing sequence, uses his hands to represent a gun as he playfully mimes the act of shooting at the group of young people harassing a woman in Chicago Union Station. However, unlike most similar Hollywood films, as its narrative progresses Bullet Ballet becomes increasingly interior and abstract. The film features a protagonist who becomes increasingly obsessed with the iconography of guns. Where Tetsuo and Tetsuo 2: Body Hammer had fetishised the combination of man and machine, and Tokyo Fist (1996) fetishised body art and body piercing (through the character of Hizuru), Bullet Ballet fetishises handguns. As Hallam notes, in all of Tsukamoto’s films technology ‘becom[es] the means through which the characters’ sexuality is expressed’ (op cit.: 93).  Bullet Ballet focuses on a salaryman, Goda (played by Tsukamoto himself), who in the early scenes of the film returns home from his job to find that his unnamed girlfriend has committed suicide in their apartment. She has shot herself, the bullet leaving a crack in the glass in the bathroom window that will remain throughout the film, acting as a signifier of Goda’s girlfriend’s absence. Her suicide is completely unexpected by Goda, and he tries to understand the reasons for her suicide. During his struggle to comprehend what has happened to him, Goda encounters a young female street punk, Chisato (Kirina Mano), who he previously saved from being hit by a subway train. Chisato calls the gang that she is a member of, and tells them that Goda tried to have sex with her. The gang beat and rob Goda. Subsequently, Goda becomes obsessed with the idea of acquiring a compact handgun. During his work as an editor of television commercials, he spends his time editing together close-ups of handguns firing and shots of the destructive impact of tank shells and nuclear missiles. Bullet Ballet focuses on a salaryman, Goda (played by Tsukamoto himself), who in the early scenes of the film returns home from his job to find that his unnamed girlfriend has committed suicide in their apartment. She has shot herself, the bullet leaving a crack in the glass in the bathroom window that will remain throughout the film, acting as a signifier of Goda’s girlfriend’s absence. Her suicide is completely unexpected by Goda, and he tries to understand the reasons for her suicide. During his struggle to comprehend what has happened to him, Goda encounters a young female street punk, Chisato (Kirina Mano), who he previously saved from being hit by a subway train. Chisato calls the gang that she is a member of, and tells them that Goda tried to have sex with her. The gang beat and rob Goda. Subsequently, Goda becomes obsessed with the idea of acquiring a compact handgun. During his work as an editor of television commercials, he spends his time editing together close-ups of handguns firing and shots of the destructive impact of tank shells and nuclear missiles.

Failing to buy a gun on the streets, Goda resorts to making his own. He goes after the gang and shoots one of them, but the handmade weapon leaves nothing more than a minor burn. Again, Goda is beaten. Meanwhile, it is revealed that Chisato’s boyfriend, Goto (Takahiro Murase), who is a member of the same gang, is also a salaryman; he is criticised by the gang leader for his attempts to make a path for himself within ‘straight’ society. As Goda comes to know Chisato and Goto better, he sees similarities between his girlfriend and Chisato, who has a death wish: one of her favourite games is to stand on the edge of a subway platform, facing away from the track, and allow the train to pass by so closely that it grazes the heels of her shoes. When Goda interrupts a street fight between the gang and another street gang, he becomes increasingly enmeshed in the worlds of Chisato and Goto, whose relationship comes to parallels Goda’s own relationship with his girlfriend.  The film builds towards an inexorably bleak conclusion, with Goda’s fate becoming increasingly enmeshed with the destinies of Chisato and Goto. Goda’s failed attempts at becoming a vigilante are pitiful: his first attempt at buying a handgun results in him being conned by a low-ranking yakuza, who instead of supplying a ‘real’ gun wraps up a water pistol and leaves it at the drop off point, robbing Goda of two and a half million yen. Next, he attempts to make his own gun, but this only results in disaster as he confronts the gang and finds that the Frankenstein’s monster of a weapon he has constructed is only capable of inflicting nothing more than a minor flesh wound. Finally, he acquires a revolver, but it is only through a woman who approaches him and asks him to marry her so that she may acquire a visa to live in Japan; in return, she offers him her dead husband’s revolver. However, his first attempt to use this revolver, interrupting a fight between Chisato’s gang and a rival street gang, results in Goda being knocked unconscious, his gun being taken from him by the leader of the gang that Chisato belongs to, and Goda being held hostage in his own flat. The film builds towards an inexorably bleak conclusion, with Goda’s fate becoming increasingly enmeshed with the destinies of Chisato and Goto. Goda’s failed attempts at becoming a vigilante are pitiful: his first attempt at buying a handgun results in him being conned by a low-ranking yakuza, who instead of supplying a ‘real’ gun wraps up a water pistol and leaves it at the drop off point, robbing Goda of two and a half million yen. Next, he attempts to make his own gun, but this only results in disaster as he confronts the gang and finds that the Frankenstein’s monster of a weapon he has constructed is only capable of inflicting nothing more than a minor flesh wound. Finally, he acquires a revolver, but it is only through a woman who approaches him and asks him to marry her so that she may acquire a visa to live in Japan; in return, she offers him her dead husband’s revolver. However, his first attempt to use this revolver, interrupting a fight between Chisato’s gang and a rival street gang, results in Goda being knocked unconscious, his gun being taken from him by the leader of the gang that Chisato belongs to, and Goda being held hostage in his own flat.

It is ultimately a film about a deep alienation that affects all of the characters. In one scene, a gang member is shown having sex with a well-dressed woman behind a nightclub: the woman is clearly there to experience ‘a bit of rough’. As the gang member aggressively takes the woman from behind, he mutters in her ear, ‘You’re stuck with a real hard job here, honey. It ain’t a Utopia here. Forget about ideal [sic], then you start to feel happy’. The scene is arguably an apt distillation of the film’s themes. All of the characters seem to be adrift in the film, struggling to find their identity in a world in which there is no room for ideals: Goto is torn between his work as a salaryman and his membership of the street gang; Goda is a salaryman who perceives himself to be a Charles Bronson-type vigilante but is utterly incompetent in that role (‘I’m already in deep shit. Even a worm turns, so to speak’, he states stoically as the gang threaten him towards the start of the film, and he is subsequently robbed and humiliated by the group of adolescents). The film is uncut and has a running time of 86:37. (Early festival screenings were reputed to be around ten minutes longer, but this represents the version of the film that was released to cinemas and on various home video formats since.)

Video

The film was shot on high contrast monochrome 16mm film. Tsukamoto’s depiction of Tokyo recalls the work of Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama and Moriyama’s roots in the radical ‘are, bure, boke’ (‘grainy, blurry, out-of-focus’) aesthetic of the experimental Japanese photography magazine Purovōku: shisō no tame no chōhatsuteki shiryō/Provoke: Provocative Documents for the Sake of Social Thought (1968-70) - along with the work of Moriyama’s mentors/contemporaries Takuma Nakahira and Yutaka Takanashi. Working against the dominant practices within photography, largely inherited from European and American photographers, this group of Japanese photographers characteristically shot on Kodak Tri-X and ‘pushed’ the film two or three stops, resulting in a grainy, high contrast image characterised by a lack of detail in the highlights and lowlights. This style of photography, and especially the work of Moriyama, has come to represent the profound alienation within urban Japanese society after the Second World War, and Tsukamoto’s reference to this photographic aesthetic seems intentional within the context of his story about rootless adolescents and alienated, masochistic salarymen. The film was shot on high contrast monochrome 16mm film. Tsukamoto’s depiction of Tokyo recalls the work of Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama and Moriyama’s roots in the radical ‘are, bure, boke’ (‘grainy, blurry, out-of-focus’) aesthetic of the experimental Japanese photography magazine Purovōku: shisō no tame no chōhatsuteki shiryō/Provoke: Provocative Documents for the Sake of Social Thought (1968-70) - along with the work of Moriyama’s mentors/contemporaries Takuma Nakahira and Yutaka Takanashi. Working against the dominant practices within photography, largely inherited from European and American photographers, this group of Japanese photographers characteristically shot on Kodak Tri-X and ‘pushed’ the film two or three stops, resulting in a grainy, high contrast image characterised by a lack of detail in the highlights and lowlights. This style of photography, and especially the work of Moriyama, has come to represent the profound alienation within urban Japanese society after the Second World War, and Tsukamoto’s reference to this photographic aesthetic seems intentional within the context of his story about rootless adolescents and alienated, masochistic salarymen.

There’s a lot of low-light photography (especially on the city streets at night) in this film, enabled by the high-speed, high contrast film stock. Some of Tsukamoto’s images (for example, a cockroach caught under a dripping tap, or those following Goda through the city streets at night) could easily have come from the pages of Provoke. Shot on 16mm with fast stock, the film has a consistent, ‘angry’ grain structure which is well-represented on this disc. This ‘angriness’ is carried over into Tsukamoto’s use of rapid editing and handheld camerawork. There’s not a lot of tonality in the highlights and lowlights due to the high contrast photography, but this is true to the original film. Black levels are very good, and on the whole this is an excellent digital simulacrum of how I remember the film looking when I saw it on the big screen during the 1999 Dublin Film Festival. The film is presented in a 1080p presentation, in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio; the film is encoded with the AVC codec. NB. Images in this review are for illustration purposes only and do not reflect the quality of this Blu-ray release.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 stereo track. There are optional English subtitles. The audio track is, like the film’s visuals, raw and, again, is represented well here, with good dynamic range. The audio track is clear throughout.

Extras

Contextual material includes: - the film’s original Japanese trailer (SD, 0:55) - a music video (SD, 3:05) using footage from the film - a UK trailer (HD, 2:23) - a three-part interview with Tsukamoto: -- ‘About Bullet Ballet’ (HD, 14:37), in which Tsukamoto discusses the origins of the film and its focus on the battles between his generation and ‘teamers’ (adolescents). -- ‘About Tokyo Fist and Bullet Ballet’ (HD, 3:23). This is carried over from Third Window’s release of Tokyo Fist and features Tsukamoto discussing the similarities between these two films. -- ‘General Thoughts’ (HD, 4:18). Again, this is carried over from Third Window’s Tokyo Fist Blu-ray and focuses largely on Tsukamoto’s reflections on the differences between film and digital capture. ‘As a director, it’s more about what you do’, he says: ‘My films are based upon what I want to do. I love film’. However, ‘due to budget and convenience’ he’s ‘been shooting digitally’ in recent years. Digital technology allows him to shoot more takes, and lighting and postproduction are also cheaper and easier with digital shoots – ‘but I still love looking at and touching film’.

Overall

I remember watching Bullet Ballet at the Dublin Film Festival in 1999. The screening was held in the big Virgin multiplex on Parnell Street (now owned by UGC and known as Cineworld Dublin). The friends with whom I visited the festival all had other obligations that evening, so I attended the screening alone; the auditorium was almost empty, and the screening finished after midnight. The film, a close study of the spiral of alienation, was exhausting and depressing. I remember staggering out of the Virgin cinema into the streets of Dublin at night-time, finding my way back to the Dublin International Youth Hostel (where I was staying), feeling utterly isolated. It’s one of the strongest, most impactful cinema experiences of my life. The film is violent but not particularly graphic: its unsettling undertones are carried by the high contrast monochrome photography, which has parallels in the work of Japanese photographers such as Daido Moriyama (who, like Tsukamoto, has drawn focus on alienation within Japanese cities). Revisiting the film almost fifteen years later, via this Blu-ray release, I found that Tsukamoto’s picture had lost none of its impact: it’s as powerful as it was when I saw it back in 1999. This Blu-ray is an excellent presentation of the film and includes some very good contextual material, although it’s worth noting that two of the three segments of the Tsukamoto interview are duplicated across this disc and Third Window’s Blu-ray release of Tokyo Fist (which we also recently reviewed, here). I remember watching Bullet Ballet at the Dublin Film Festival in 1999. The screening was held in the big Virgin multiplex on Parnell Street (now owned by UGC and known as Cineworld Dublin). The friends with whom I visited the festival all had other obligations that evening, so I attended the screening alone; the auditorium was almost empty, and the screening finished after midnight. The film, a close study of the spiral of alienation, was exhausting and depressing. I remember staggering out of the Virgin cinema into the streets of Dublin at night-time, finding my way back to the Dublin International Youth Hostel (where I was staying), feeling utterly isolated. It’s one of the strongest, most impactful cinema experiences of my life. The film is violent but not particularly graphic: its unsettling undertones are carried by the high contrast monochrome photography, which has parallels in the work of Japanese photographers such as Daido Moriyama (who, like Tsukamoto, has drawn focus on alienation within Japanese cities). Revisiting the film almost fifteen years later, via this Blu-ray release, I found that Tsukamoto’s picture had lost none of its impact: it’s as powerful as it was when I saw it back in 1999. This Blu-ray is an excellent presentation of the film and includes some very good contextual material, although it’s worth noting that two of the three segments of the Tsukamoto interview are duplicated across this disc and Third Window’s Blu-ray release of Tokyo Fist (which we also recently reviewed, here).

References Hallam, Lindsay Anne, 2011: Screening the Marquis the Sade: Pleasure, Pain and the Transgressive Body in Film. London: McFarland Schilling, Mark, 2010: ‘Tokyo Fist (capsule review)’. In: Berra, John (ed), 2010: Directory of World Cinema: Japan. London: Intellect Books: 53-4 This review has been kindly sponsored by Third Window Films.

|

|||||

|