|

The Film

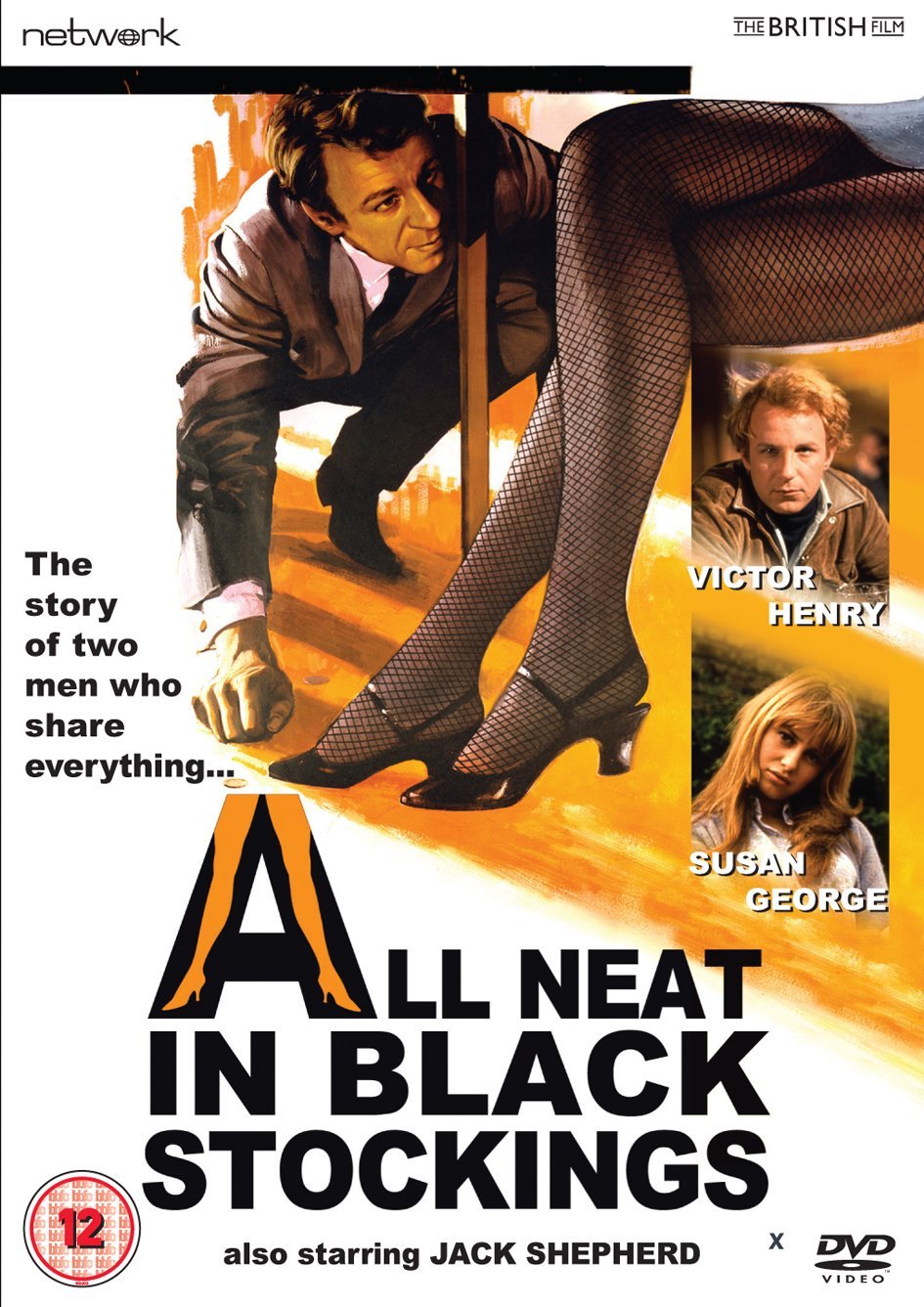

All Neat in Black Stockings (Christopher Morahan, 1969) All Neat in Black Stockings (Christopher Morahan, 1969)

The youth-oriented sex comedy proliferated during the late 1960s and early 1970s: it was a subgroup of films, usually focusing on sexually frustrated young men from the working classes (or sometimes lower middle classes) attempting to negotiate the changing attitudes that accompanied the sexual revolution and the era of Women’s Lib, that is perhaps best represented by Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush (Clive Donner, 1967), which focuses on sixth former Jamie McGregor’s (Barry Evans) quest to lost his virginity. These rather light ‘coming of age’ sex comedies, which were in essence comedies of manners, arguably ‘grew up’ into the more explicit and far less restrained Confessions of… films of the 1970s, beginning with Val Guest’s Confessions of a Window Cleaner (1974). This subgroup of pictures, arguably Britain’s slightly more repressed equivalent of the sexploitation films that began to be produced in Europe and American during the 1960s and 1970s, are usually said to have been kick-started by the success of Richard Lester’s The Knack… and How to Get It, which won the Palme d’Or in 1965 (see Spencer, 2008: 106). The Knack… was a youth-oriented film which focused on the sexual competition that arises between three young male friends (Michael Crawford, Ray Brooks and Donal Donnelly) when they encounter the attractive Nancy (Rita Tushingham).

Alfie (Lewis Gilbert, 1966) is sometimes lumped in with the sex comedies of this period, and on its release the film was marketed as such; but Alfie is a rather different film to the majority of its contemporaries. Although it features a sex-obsessed young man, the titular Alfie Elkins (Michael Caine), ‘[v]iewing the film thirty years after its release, it no longer seems a jaunty, innovative comedy celebrating an irresistible working class lad. Instead, it comes across as a sobering portrait of a sad irresponsible male’ whose ‘“adventures” include abandoning his girlfriend and their son, impregnating a friend’s wife, walking out on her suffering during a backyard abortion, and then provoking a young girl, Annie, into leaving his flat when she gets to be too much of a habit’ (Mayer, 2003: 5). As Mayer notes, film melodramas ‘traditionally demand the redemption of the rake, the realization that marriage or a monogamous relationship is genuinely more satisfying than casual sex’ (ibid.). However, Alfie refuses this: at the end of the film, Alfie has not changed his attitude towards sex and will most likely continue in his casual, offhand treatment of the women who have misfortune to become involved with him. The only change comes in Alfie’s realisation that his lifestyle is not offering him any sense of fulfilment whatsoever. It’s a bleak and cynical conclusion that undercuts any attempt to market the film as a comedy.

Ostensibly a ‘coming of age’ sex comedy, All Neat in Black Stockings has much more in common with Alfie than with The Knack… or the later Confessions of… films. Its resolution has some strong similarities with that of Alfie, and although the film, like Alfie, was sold as a comedy, it is actually quite a downbeat, cynical examination of the relationships between young men and women. As with Alfie, there are some humorous moments, but (like Alfie again) the bitter ending underscores the solemnity of the film’s approach to its subject. The film has acquired additional retroactive significance owing to the tragic events that befell its lead actor, Victor Henry (the stage/screen name of Alex Henry), for whom this was his last film. A rising young star who had appeared in Michael Reeves’ The Sorcerers (1967) and Peter Watkins’ Privilege (1967), Henry’s life and career were both tragically cut short when he was knocked down by a car. The accident left Henry in a coma which lasted over a decade, and sadly he passed away in 1985. Ostensibly a ‘coming of age’ sex comedy, All Neat in Black Stockings has much more in common with Alfie than with The Knack… or the later Confessions of… films. Its resolution has some strong similarities with that of Alfie, and although the film, like Alfie, was sold as a comedy, it is actually quite a downbeat, cynical examination of the relationships between young men and women. As with Alfie, there are some humorous moments, but (like Alfie again) the bitter ending underscores the solemnity of the film’s approach to its subject. The film has acquired additional retroactive significance owing to the tragic events that befell its lead actor, Victor Henry (the stage/screen name of Alex Henry), for whom this was his last film. A rising young star who had appeared in Michael Reeves’ The Sorcerers (1967) and Peter Watkins’ Privilege (1967), Henry’s life and career were both tragically cut short when he was knocked down by a car. The accident left Henry in a coma which lasted over a decade, and sadly he passed away in 1985.

In this film, adapted from the novel by Jane Gaskell (with a script by Gaskell herself), Henry plays 20 year old window cleaner Ginger. Ginger lives in a bedsit with his friend Dwyer (Jack Shepherd), and the two display a casual chauvinism, swapping girlfriends with one another, that goes unchallenged by most of the women that they encounter. In the opening sequence, whilst cleaning the windows of the local hospital, Ginger sneaks into the hospital to ask a pretty Italian nurse, Babette (Jasmina Harnzavi), for a date; in the hospital, he also visits an elderly man, Old Gunge (Terence De Marney), who gives Ginger the key to his home and asks him to take care of his pets. Ginger visits Old Gunge’s house, finding it to be a large, secluded and mildly derelict building that is filled with animals – birds, fish, reptiles. During his date with Babette, Ginger eyes pretty young primary school teacher Jill (Susan George) and her friend Carole (Vanessa Forsyth). The virginal Jill is unlike most of the young women that Ginger knows: she doesn’t throw herself at his feet and refuses to sleep with him, and gradually Ginger comes to realise that he is falling in love with her. However, he faces the disapproval of Jill’s mother (Clare Kelly), a devoutly middle class widow with whom Jill lives in her semi-detached house, and who looks down upon the lowly Ginger.

Visiting his sister Sicily (Anna Cropper) and her idle husband Issur (Harry Towb), who claims to be a painter but is nothing more than a sponger, Ginger discovers that he is to be an uncle again: Sicily already has one young child and another on the way. Issur is incapable of caring for Sicily and the children, forcing his family to live in a rundown rented accommodation, and so Ginger suggests that Sicily and her child take temporary residence in Old Gunge’s house – at least until Old Gunge is discharged from the hospital. However, shortly after handing the keys over to Sicily, Ginger discovers that Issur has exploited Ginger’s offer: Issur entertains his mistress in Old Gunge’s house, and after moving Sicily and the child into the house, he hosts a wild party which results in the house being wrecked. Ginger attempts to break up the party; whilst he does so, he asks Dwyer to take care of Jill. After the party has dispersed, Ginger discovers Jill in a tearful state: it seems that Dwyer has manipulated the situation so that Jill will sleep with him. As the weeks go by, Jill discovers that she is pregnant to Dwyer. However, Dwyer has no interest in Jill. Reasoning that ‘It’s not his [the baby’s] fault, the poor little sod’, Ginger asks Jill to marry him. Discovering Jill’s pregnancy, Jill’s mother reluctantly agrees to the marriage.

Ginger rents a terraced house, but Jill obstinately refuses to live in it, saying she wants the family to live in her mother’s semi. Ginger moves in with Jill and her mother. Whilst Jill is in the hospital giving birth, Ginger goes out and gets drunk. He returns home and is confronted by Jill’s mother. In his drunken state, Ginger sleeps with Jill’s mother who, lonely, doesn’t resist his advances. When Jill returns with the baby, Ginger and Jill’s relationship grows colder: the baby reminds Ginger of Dwyer, and he shows little interest in either the child or Jill. He leaves the house for work, leaving the lonely Jill to cuddle the poor child, and taking his lunch break in a local café, Ginger – clearly dissatisfied with his new, settled lifestyle – begins to flirt openly with a pretty young waitress. As the film closes, Ginger’s smile, directed at the pretty waitress, changes to a reflective look of dissatisfaction and tears well in his eyes. He is isolated within the frame, seated at the table in the café, more alone than he was at the start of the narrative. Ginger rents a terraced house, but Jill obstinately refuses to live in it, saying she wants the family to live in her mother’s semi. Ginger moves in with Jill and her mother. Whilst Jill is in the hospital giving birth, Ginger goes out and gets drunk. He returns home and is confronted by Jill’s mother. In his drunken state, Ginger sleeps with Jill’s mother who, lonely, doesn’t resist his advances. When Jill returns with the baby, Ginger and Jill’s relationship grows colder: the baby reminds Ginger of Dwyer, and he shows little interest in either the child or Jill. He leaves the house for work, leaving the lonely Jill to cuddle the poor child, and taking his lunch break in a local café, Ginger – clearly dissatisfied with his new, settled lifestyle – begins to flirt openly with a pretty young waitress. As the film closes, Ginger’s smile, directed at the pretty waitress, changes to a reflective look of dissatisfaction and tears well in his eyes. He is isolated within the frame, seated at the table in the café, more alone than he was at the start of the narrative.

The film’s resolution has more in common with Alfie than with most of the other ‘coming of age’ sex comedies of the era: it’s a devastating denouement in which the viewer is left with a sense of the dissatisfaction experienced by all of the major characters. Ginger and Jill are in an unhappy relationship, with Ginger resenting the baby; the issue of Ginger’s relationship with Jill’s mother is unresolved; Old Gunge has returned home to find his house ruined by Issur’s wild parties, but he takes pity on Sicily (who has been abandoned by Issur) and allows her to stay in the house as his live-in housekeeper. The final scene suggests that although he is alienated from his former friend Dwyer, Ginger will continue to lust after and pursue attractive young women – especially those wearing the black stockings alluded to in the film’s title (the waitress, like Babette and Jill in their respective introductory scenes, is wearing black stockings). However, the transformation of his smile into a blank, reflective stare suggests that his outwardly chipper personality hides an inner torment, and that his lust (and the pursuit of it) offers him little to no satisfaction. The moment is beautifully played by Henry and, without dialogue, arguably says as much as Michael Caine’s closing monologue in Alfie.

The film’s ironic perspective on the casual chauvinism of its young male protagonist’s world is perhaps the result of both novel and film having been written by a female author. Jane Gaskell, a great grandniece of North and South author Elizabeth Gaskell, was during the 1950s and 1960s known as a writer of horror and fantasy novels. In their crypto-feminist approach to the genre, Gaskell’s horror fiction has invited comparison with Angela Carter, whose works of fiction (such as The Bloody Chamber, 1979) reconfigured traditional folk/fairy tales and gave them a feminist ‘spin’. During the 1960s, Jane Gaskell focused on ‘counterculture contexts and values, refocusing them through a neo-Gothic prism that added a piquant frisson to otherwise mundane bohemian lifestyles’ (Latham, 2011: 123). In this novel, and in her similar novel Attic Summer (1969), ‘Gaskell showed the corrupt hedonism that marked much of the so-called sexual revolution whose promised liberations were often merely screens for cynical lusts and aimless sadism’ (ibid.). Latham’s distillation of the themes of Gaskell’s source novel works equally well for Morahan’s film adaptation, which although marketed as a sex comedy seems largely faithful to Gaskell’s critical perspective on the ‘sexual revolution’. (Gaskell’s novel, however, is probably mostly remembered for containing the first documented use of the word ‘plonker’ – and this film marks the first onscreen use of that word, which would become familiar throughout the 1980s thanks to Del Boy’s appropriation of in the long-running sitcom Only Fools and Horses; BBC, 1981-91.)

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1, with anamorphic enhancement. Shot in Eastmancolor, the film has a vibrant, colourful aesthetic, which is represented well on this transfer. There is some intermittent print damage: one scene in particular suffers from some noticeable vertical scratches on the print. The age of the emulsions is evident throughout the film: some scenes show a pronounced green/yellow shift that makes the actors look jaundiced. However, it’s perfectly watchable, and considering the rarity of the film, it’s a more than acceptable presentation of the picture.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track, which shows a little damage here and there but is audible throughout. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes a textless trailer (2:36) and stills gallery (1:37). Some DVD-Rom material is also included: a pressbook, and an exploitation campaign booklet. Both are presented as PDF files.

There is also a deleted scene (1:09): presented without any sound whatsoever, this scene is an extension of the one in which Dwyer scams people on the streets of London so as to acquire the money with which he intends to flee to Jersey. Dwyer’s plan involves stopping men who are passing by and promising them a ‘good time’ with a young women: Dwyer takes the men’s money and directs them to a building which is, of course, a dummy. In the main feature, we see Dwyer successfully con one young man; this silent deleted scene depicts Dwyer performing the same trick on a middle aged businessman.

The biggest extra on this disc is a fullframe presentation of the film (95:31). The difference in running time between this presentation of the film and the anamorphic main feature is down to the fact that this fullframe version bizarrely includes the deleted scene mentioned above (which is still presented without sound).

Overall

All Neat in Black Stockings was originally intended to be directed by Lindsay Anderson, who was offered the project in 1967. However, Anderson turned down the project after a bad experience working on a commercial for Kellog’s cereal with the crew with which the film was scheduled to go into production. Anderson cited the ‘laziness’ and ‘we’ll get away with it’ approach of his colleague Leon Clore as his decision to turn down All Neat in Black Stockings: ‘[t]he idea of making a film with him as producer – All Neat in Black Stockings – is really unreal’ (Anderson, quoted in Sutton, 2005:24-5). Given Anderson’s proclivity for experimental approaches, it would have been interesting to see what Anderson would have done with this film: he may very well have played up the Gothic aspects (for example, Old Gunge’s huge, largely decrepit house, into which Ginger moves his abused sister and her unruly husband). Nevertheless, Morahan – an experienced television director who had only directed one feature film, Diamonds for Breakfast (1968), prior to this – handles the film well, taking a naturalistic approach to the material and ensuring that the film is more bitter than sweet. There are some wonderfully subtle moments in the film, such as the closing sequence in the café which suggests that an unhappy Ginger will continue his philandering ways, destroying his new family but also finding no individual satisfaction. Such scenes are handled beautifully by both Morahan and Henry. All Neat in Black Stockings was originally intended to be directed by Lindsay Anderson, who was offered the project in 1967. However, Anderson turned down the project after a bad experience working on a commercial for Kellog’s cereal with the crew with which the film was scheduled to go into production. Anderson cited the ‘laziness’ and ‘we’ll get away with it’ approach of his colleague Leon Clore as his decision to turn down All Neat in Black Stockings: ‘[t]he idea of making a film with him as producer – All Neat in Black Stockings – is really unreal’ (Anderson, quoted in Sutton, 2005:24-5). Given Anderson’s proclivity for experimental approaches, it would have been interesting to see what Anderson would have done with this film: he may very well have played up the Gothic aspects (for example, Old Gunge’s huge, largely decrepit house, into which Ginger moves his abused sister and her unruly husband). Nevertheless, Morahan – an experienced television director who had only directed one feature film, Diamonds for Breakfast (1968), prior to this – handles the film well, taking a naturalistic approach to the material and ensuring that the film is more bitter than sweet. There are some wonderfully subtle moments in the film, such as the closing sequence in the café which suggests that an unhappy Ginger will continue his philandering ways, destroying his new family but also finding no individual satisfaction. Such scenes are handled beautifully by both Morahan and Henry.

For many years, the film has been difficult to see: this is its debut on digital home video, and television airings are quite rare. This disc contains a good presentation of the film and some interesting, though minor, contextual material. It’s a fascinating film overall, though it’s ultimately quite depressing; it’s certainly more interesting than its reputation as one of the era’s many youth-oriented sex comedies might suggest.

References:

Latham, Rob, 2011: ‘Gaskell, Jane’. In: Joshi, S T (ed), 2011: Encyclopedia of the Vampire: The Living Dead in Myth, Legend, and Popular Culture. London: Greenwood: 123-4

Mayer, Geoff, 2003: Guide to British Cinema. London: Greenwood Publishing

Spencer, Kristopher, 2008: Film and Television Scores, 1950-1979: A Critical Survey by Genre. London: McFarland

Sutton, Paul, 2005: Turner Classic Movies British Film Guide: ‘If….’. London: I B Tauris

This review has been kindly sponsored by Network Releasing. Please visit their homepage and online shop: www.networkonair.com

| The Film: |

Video: |

Audio: |

Extras: |

Overall: |

|