|

The Film

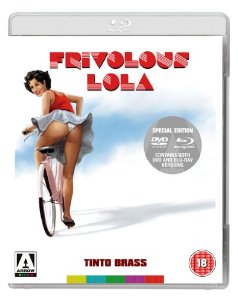

Frivolous Lola AKA Monella (Tinto Brass, 1998) Frivolous Lola AKA Monella (Tinto Brass, 1998)

Once declared by Roberto Rossellini as one of the most gifted filmmakers in modern Italy, during the mid-1970s Giovanni Tinto (under his pseudonym Tinto Brass) seemed to break with the more experimental narrative films that he had, till that time, been associated with. During the 1960s, Brass made a group of pictures with a curious Pop Art-type aesthetic: these experimental narrative films, often with strong political content, included the Italo-Western Yankee (1966), the thrilling all’italiana Col cuore in goia (Deadly Sweet, 1967), Nerosubianco (Attraction, 1969), L’urlo (The Howl, 1968), and the two films Brass made with the husband-and-wife acting team of Franco Nero and Vanessa Redgrave, Dropout (1971) and La vacanza (The Vacation, 1971). The turning point in Brass’ career came with Salon Kitty (1975): the first feature Brass directed after a five year break following La vacanza, which had been a commercial flop, Salon Kitty was still heavily political but featured increasing erotic content. Subsequently, Brass would direct (and remove his name from) the infamous Caligula (1979), a less successful mix of sex and politics; and throughout the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s Brass carved his niche within the realm of erotic cinema, delivering films that mixed reflection on cultural and political issues within the zeitgeist with Brass’ own fetishistic interest in the voluptuous derrieres of his curvy actresses and a recurring theme of voyeurism.

Brass’ films became increasingly concerned with earthy excesses and began to include near-hardcore material: both male and female nudity in his films was graphic almost to the point of being confrontational. Because of this mixture of satire and eroticism, Brass’ films continue to divide viewers: fans of Brass’ pictures are drawn to his combination of satire and sleaze, seeing the sexual excesses and open vulgarity of his films as a key element of their subversive worldview. On the other hand, critics of Brass often denounce him as a director of tacky sex pictures that aspire to arthouse status. However, these are not mutually exclusive perspectives: arguably, Brass’ work is interesting precisely because of its curious mixture of the sensual and the political, exploring the relationships between desire, politics, sexuality and power.

Frivolous Lola opens and closes with shots of Brass, in a cameo appearance, that reinforce his control over the narrative. It’s a highly reflexive film in many ways, with Patrick Mower’s character Andre, and his obsession with photographing the female rump, arguably standing in for Brass himself. The narrative takes place sometime during the 1950s (the costumes, vehicles, and Andre’s twin-lens reflex camera are all indexical of the film’s temporal setting). Brass has often compared himself with the American sexploitation film director Russ Meyer, and in some ways Frivolous Lola is the most Russ Meyer-like of Brass’ pictures: Lola (Anna Ammirati) herself drives the narrative and is larger than life, often filmed from a low angle to emphasise her stature and in partial silhouette to reinforce the dimensions of her physique.

The film’s plot is simple. Engaged to Masetto (Max Parodi), the diligent and conformist son of a baker, Lola is a freewheeling spirit who is frustrated by Masetto’s belief that both of them should remain virgins until their wedding night. She makes numerous attempts to seduce Masetto, including visiting him at his family’s bakehouse and (unhygenically) persuading him to caress her intimately amidst the flour sacks in the storage room. However, Masetto’s mother disapproves of her son’s relationship with Lola: Lola’s mother Zaira (Serena Grandi) is known in the vicinity as a woman of loose morals owing to the fact that she had Lola out of wedlock. Compounding the issue, Zaira has taken up with Andre (Patrick Mower), a wealthy man who may or may not be Lola’s biological father. Andre and his associate Pepe (Antonio Salines) are amateur pornographers who show a preference for photographing the derrieres of their female subjects. (Their work, shot on a medium format twin-lens reflex camera, shows a striking similarity to that of Helmut Newton.) In a flashback, we are shown that Lola’s sexual awakening came when she saw Andre photographing, and then fucking, one of his models; she seems to have inherited Andre’s voracious sexual appetite. She is also mercurial, confusing Andre: pursuing him one instant, and then abandoning him the next. The film’s plot is simple. Engaged to Masetto (Max Parodi), the diligent and conformist son of a baker, Lola is a freewheeling spirit who is frustrated by Masetto’s belief that both of them should remain virgins until their wedding night. She makes numerous attempts to seduce Masetto, including visiting him at his family’s bakehouse and (unhygenically) persuading him to caress her intimately amidst the flour sacks in the storage room. However, Masetto’s mother disapproves of her son’s relationship with Lola: Lola’s mother Zaira (Serena Grandi) is known in the vicinity as a woman of loose morals owing to the fact that she had Lola out of wedlock. Compounding the issue, Zaira has taken up with Andre (Patrick Mower), a wealthy man who may or may not be Lola’s biological father. Andre and his associate Pepe (Antonio Salines) are amateur pornographers who show a preference for photographing the derrieres of their female subjects. (Their work, shot on a medium format twin-lens reflex camera, shows a striking similarity to that of Helmut Newton.) In a flashback, we are shown that Lola’s sexual awakening came when she saw Andre photographing, and then fucking, one of his models; she seems to have inherited Andre’s voracious sexual appetite. She is also mercurial, confusing Andre: pursuing him one instant, and then abandoning him the next.

Masetto’s breaking point comes when, one evening at the local café, Lola flirts openly with three soldiers who are stationed in the area. The soldiers mock Masetto, suggesting that women in northern Italy are known for their sluttish tendencies. The scene ends in a fight during which Lola flees the scene in the car of a passing furrier. The furrier attempts to seduce Lola, who poses as an ‘easy lay’; but she changes her mind, or perhaps realises the game has been taken too far, and manages to escape from the car, walking home in the pouring rain. At home, she offers herself to Andre, stripping off her wet clothes in front of him and asking him to dry her. Unsure as to whether Lola is his biological daughter, Andre resists; they are interrupted by Zaira, who during a blazing row with Andre reveals that he is not Lola’s ‘true’ father. Andre insists that he has no sexual interest in Lola. Meanwhile, angry with Lola, Masetto visits prostitute Wilma (Francesca Nunzi), to whom he loses his virginity. The next day, Lola visits Masetto at work and tells him she was raped by the furrier. Enraged by jealousy and offered legitimation by his belief that Lola is no longer a virgin, Masetto has sex with her amongst the sacks of flour in the storage room. He is angry when he realises that she lied to him about the furrier, but realising his love for Lola, Masetto has a change of heart and submits himself to her mercurial temperament. In a wonderful ceremony, the pair marry, with Andre and Zaira gazing on as loving parents.

The film’s Italian title, Monella, which is also used as a recurring refrain within the song that opens and closes the picture, is a slang term for a tomboy or rascal, and may sometimes be used to describe a young woman who is something of a cocktease (what may be described as a hussy). It suggests a certain sense of (perhaps erotic) playfulness, and Lola’s freewheeling nature is established immediately through the titles sequence, in which she rides through the village, her rump deliberately on display. Her display provokes responding displays of desire amongst the men she passes (‘Life is so short, but an ass gives it meaning’, one elderly man observes), including two priests who follow her bicycle and, when she leaves it parked outside Masetto’s family’s bakery, sniff its seat which still glistens with the sweat from her rump. The incident with the priests is one index of Brass’ playfully satirical approach to erotic cinema. Later in the film, Zaira is shown in the kitchen of the home she shares with Andre, an elderly priest seated in the corner of the room. Zaira offers the priest the ‘rump’ of the salami she has prepared for Andre. The priest caresses an ear of sweetcorn, and Brass pans away from him to show the priest’s shadow; the priest’s action with the ear of sweetcorn thus appears, like a perverse piece of shadow theatre, as if the priest is stroking a huge phallus. In such a way, Brass lightly pokes fun at the church.

Brass is more sympathetic towards Andre, despite the character’s apparent sexual attraction to Lola (which he resists – a fact that in Brass’ unrepentantly chauvinistic worldview suggests he is somehow heroic). Andre is an interesting character, played with masculine authority by Patrick Mower. He has turned his back on his past, and his wealth, by taking up with Zaira, driven by his desire for her buxom charms – which is represented in his fetishistic photography of her backside. Andre is content with his parochial lifestyle, despite his prior experiences of the world and all it has to offer: ‘Here, at least, I laugh at the trouble the world’s getting itself into’, he tells Pepe, ‘It’s enough for me to have what I want on my plate and in my bed. And that’s the joie de vivre, Pepe’. Brass is more sympathetic towards Andre, despite the character’s apparent sexual attraction to Lola (which he resists – a fact that in Brass’ unrepentantly chauvinistic worldview suggests he is somehow heroic). Andre is an interesting character, played with masculine authority by Patrick Mower. He has turned his back on his past, and his wealth, by taking up with Zaira, driven by his desire for her buxom charms – which is represented in his fetishistic photography of her backside. Andre is content with his parochial lifestyle, despite his prior experiences of the world and all it has to offer: ‘Here, at least, I laugh at the trouble the world’s getting itself into’, he tells Pepe, ‘It’s enough for me to have what I want on my plate and in my bed. And that’s the joie de vivre, Pepe’.

For Andre, sexuality and other earthly pleasures are the key to happiness. In this sense, the character is the expression of the worldview that runs throughout many of Brass’ films. When Lola pries in his study, Andre stops her from opening a drawer: ‘I’m like Bluebeard’, he tells her, ‘Every door except one’. Andre is introduced in his study, as he and Pepe look at slides of the models for Andre’s photography. ‘Without heads, they’re more beautiful’, Andre observes in relation to the women – who, as in much erotic photography, are predominantly framed within the photographs in compositions that eliminate their heads, thus reducing them to signifiers of their sex (pronounced breasts, equally pronounced buttocks). The monochrome, square compositions immediately call to mind the photographs of Helmut Newton – such as Newton’s ‘Self Portrait with Wife and Models’ (1980), in which Newton focuses on the behind of his model, whilst a mirror positioned in front of her reflects her nude form and Newton himself, gazing into the waist-level viewfinder of his Rolleiflex camera. IN response to Andre’s claim, Pepe announces that ‘The body is more expressive than the face. And above all, it doesn’t lie [….] En effet, the rest is little more than a distraction’. To this, Andre responds, ‘Oh, you can say it’s a lie, a mischief, or even worse, a curse. Work, success, progress, all bullshit. Only there, I am’ – and Brass cuts to a slide depicting a close-up of a woman’s buttocks.

Likewise, when Masetto visits her, Wilma offers a monologue on modern culture. She is introduced reading a book about economics, and it appears she is an autodidact, fully cognisant of the economy that drives (and is driven by) human sexuality. She deduces that Masetto is there ‘to treat someone badly. That’s the trouble with private enterprise. Everyone’s in such a hurry, there’s no time for intimacy. In the old days, in the brothels, you joked around with clients, you had conversations’. When Masetto explains his situation to Wilma and asks her, ‘Why does Lola spite me?’, she reminds him, ‘My dear boy. Don’t you know that love is all spite’.

Lola’s sexual appetite is immense, driven by her sexual frustration, and apparently inherited from Andre – even though he is not her biological father. She displays the classic Electra complex: when she is frustrated in her pursuit of Masetto’s full sexual attention, she turns to the man she believes to be her father, and her sexual awakening, a flashback suggests, came when she saw her father photographing Zaira before taking her from behind – in full view of both Pepe and Lola. However, this flashback is framed as part of a sequence in which Lola masturbates after having been rejected by Masetto, and it’s not one hundred per cent clear whether it is to be interpreted as an accurate depiction of Lola’s past or nothing more than a masturbatory fantasy involving the father figure in her life. Her attitude towards sex is underscored by a conversation with Masetto in which he reinforces his desire to remain a virgin until his wedding night: she tells him, ‘Listen, Masetto: virginity is like a crumb of bread: the first bird that comes along takes it away’.

Of course, Masetto loses his virginity not to Lola but to the prostitute Wilma; and whilst he is angered by the suggestion that Lola has had a sexual encounter with the furrier (he seems more enraged by the fact that she is no longer a virgin than by the fact that she claims she has been raped), his hypocrisy is never given consequence within the narrative. Lola never finds out about Masetto’s indiscretion, and the only reference that is made to it later in the narrative is during the wedding sequence, in which we see Wilma gazing on contentedly as Lola and Masetto declare their love for one another.

Video

The 1080p presentation is in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1, although the film’s intended aspect ratio is 1.66:1. The compositions sometimes seem very tight along the vertical axis: there’s a sequence in which Masetto’s head is cropped by the framing, which seems somewhat unnatural (and ironically connects with Andre and Pepe’s conversation about their female models).

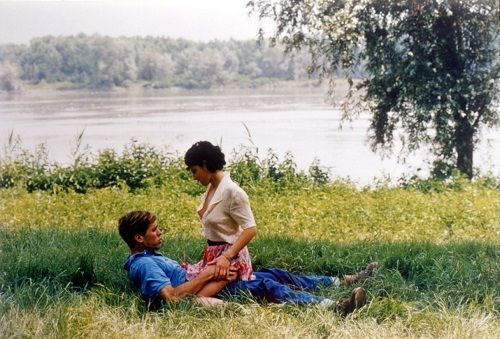

As with most of Brass’ films, Frivolous Lola has an interesting aesthetic: the compositions are dominated by symmetry. The whole film is shot with a hazy, soft-focus approach to photography. There’s a lot of diffuse light, with Brass often framing his characters against light backdrops and exposing for the midtones. In light of this, this HD presentation is satisfying but hardly ‘showy’.

Audio

Audio is presented via an option of an English LPCM 2.0 stereo track, with optional English HoH subtitles, and the original Italian audio, presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track with newly-translated English subtitles. Audio/subtitle options can’t be changed ‘on the fly’ and must be adjusted by accessing the main menu.

Both audio tracks are perfectly fine, although there seems to be a slight variation in pitch between the two (perhaps one is sourced from a PAL transfer?)

Extras

Extras include the film’s trailer (2:21) and Italian-language opening and closing credits

Overall

Frivolous Lola is an interesting picture from Brass. It doesn’t deviate from the Brass formula, and fans of Brass’ mixture of eroticism and satire, sex and philosophy, will find much to enjoy here. The presentation on this Blu-ray is very good, despite the too-tight framing (1.66:1 seems to be the preferred aspect ratio with this one, as with many of Brass’ pictures). However, given the use of soft-focus photography which contains much diffuse light, it’s hardly ‘showy’. Nevertheless, it’s a vast improvement over the various DVD presentations. The only disappointing aspect about Arrow’s recent releases of Brass’ films is the relative paucity of contextual material on the discs themselves. Given the revitalised interest in Brass’ work that followed the 2013 Venice Film Festival (and the documentary IsTintoBrAss – which would be an interesting addition to a future release of any Brass picture), some retrospective interviews or even a documentary about Brass would make a welcome addition. (Retail versions of these Brass releases nevertheless contain very good printed material, in the form of extensive booklets.) Regardless, this is a release with which fans of Brass’ pictures will no doubt be very happy.

References:

Calabrese, Carlo, 2004: La chiave di lettura di Tinto Brass. Rome: Edizioni Interculturali

Lori, Stefano, 2000: Tinto Brass. Rome: Gremese Editore

Sanchez-Moraleda, Martina & Castoldi, Gian Luca, 2003: ‘Tinto Brass Interviewed’. In: Fenton, Harvey (ed), 2003: Flesh & Blood Compendium. London: FAB Press

NB. Please note that the images used in this review are for the purposes of illustration only and in no way reflect the transfer included in Arrow’s Blu-ray release.

|