|

|

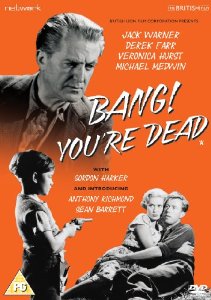

Bang! You're Dead AKA Game of Danger

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th February 2014). |

|

The Film

Bang! You’re Dead AKA Game of Danger (Lance Comfort, 1954) Bang! You’re Dead AKA Game of Danger (Lance Comfort, 1954)

Lance Comfort directed some of the most interesting British crime films of the 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s, although at the time his work was largely ignored by critics. In 1954, he made two films about murders in which the wrong suspect is pursued by the police: Eight O’Clock Walk, in which Richard Attenborough is falsely accused of murdering a young girl; and Bang! You’re Dead, in which a young boy accidentally shoots an unpopular local man with a loaded revolver that he finds in an abandoned US Army building, only for another local man to be blamed for the crime. Both of these ‘wrong man’ narratives may suggest some similarities with the work of Alfred Hitchcock, although Comfort’s films were in many ways more allied with contemporaneous ‘social problem’ pictures such as Basil Dearden’s The Blue Lamp (1950) than with the paranoid thrillers Hitchcock was making in America at the time. However, in 1961, Hitchcock directed an episode in the seventh season of his television anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents (Universal, 1955-62) that also carried the title ‘Bang! You’re Dead’. The episode had a similar focus to Comfort’s film, revolving around a six year old boy named Jackie Chester (Billy Mumy): Jackie discovers his uncle’s loaded revolver and, unable to differentiate it from a toy gun, plays ‘cowboys’ with it. Unlike Comfort’s film, Hitchcock’s episode shies away from implicating Jackie in the death of another human being: in the climax of the episode, Jackie almost kills the family’s maid, but she is saved by the boy’s parents. Comfort’s film focuses on Cliff (Anthony Richmond), the young son of a lonely widower (Jack Warner). Cliff and his father live amongst a community of squatters, who in the aftermath of the war have taken to living in the remains of an old US army base in the English countryside. The families who live within this community are poor, and amongst their number is Ben Jones (Philip Saville), a slightly smarmy young man who is one of the few people within the community to have a steady job. Jones is disliked because ‘He ain’t one of us’, Cliff’s father tells landlord of the local pub: ‘That job he [Jones] got during the war should have been given to one of us when we came back’. Jones is also disliked by Bob Carter (Michael Medwin), another young man who competes with Jones for the affections of Hilda (Veronica Hurst), the landlord’s daughter. Encouraged by his father, Cliff likes to play cowboys amongst the corrugated huts that make up the US army base, and one day the young boy finds a loaded revolver in one of the buildings. Believing the gun to be a toy, he ‘holds up’ Jones who, traveling through the woods after an argument with Carter over Hilda, plays along and gives Cliff his pocket watch. The gun discharges accidentally, leaving Jones dead. Unaware of what he’s done, Cliff runs away from the scene. Carter becomes the main suspect in the death of Jones. Meanwhile, Cliff gradually comes to a realisation of what he has done.  The title of Bang! You’re Dead is taken from the lyrics of the song that the young boy Willy (Sean Barrett) plays obsessively on the phonograph that he salvages from the ruins of the same US army base in which his friend Cliff finds the loaded revolver. The cold and inhuman corrugated steel huts left behind by the US army after the Second World War have become the homes for a squatter community torn asunder and displaced by that conflict, the impact of which reverberates throughout this film. It is an utterly bleak depiction of postwar life, characterised by poverty. Brian McFarlane notes that ‘[t]he film gives the impression of looking at the underside of English society, not criminal but just bleak’: McFarlane suggests that Comfort ‘uses the pastoral beauty of trees and sky to comment on the drabness of the human lives involved’ (1999: 133). McFarlane contrasts the film with Asquith’s The Way to the Stars (1945), arguing that Comfort’s picture ‘takes a clear-eyed look at the detritus left in [the] wake’ of the US presence in England during the war (ibid.). The film, McFarlane suggests, intentionally ‘looks genuinely strange, the works of nature and those of man in uneasy contrast’ (ibid., emphasis in original). The title of Bang! You’re Dead is taken from the lyrics of the song that the young boy Willy (Sean Barrett) plays obsessively on the phonograph that he salvages from the ruins of the same US army base in which his friend Cliff finds the loaded revolver. The cold and inhuman corrugated steel huts left behind by the US army after the Second World War have become the homes for a squatter community torn asunder and displaced by that conflict, the impact of which reverberates throughout this film. It is an utterly bleak depiction of postwar life, characterised by poverty. Brian McFarlane notes that ‘[t]he film gives the impression of looking at the underside of English society, not criminal but just bleak’: McFarlane suggests that Comfort ‘uses the pastoral beauty of trees and sky to comment on the drabness of the human lives involved’ (1999: 133). McFarlane contrasts the film with Asquith’s The Way to the Stars (1945), arguing that Comfort’s picture ‘takes a clear-eyed look at the detritus left in [the] wake’ of the US presence in England during the war (ibid.). The film, McFarlane suggests, intentionally ‘looks genuinely strange, the works of nature and those of man in uneasy contrast’ (ibid., emphasis in original).

The film is in many ways utterly bleak: the death of Jones is shown in the opening sequence, with much of the rest of the film taking place as an extended analepsis/flashback. From the outset, the audience is made aware of the fact that Cliff has, albeit accidentally, caused the death of Jones, and although at the end of the film the detective in charge of the case does not take him into custody, we are left with the awareness that Cliff and his father will most likely never come to terms with what has happened. Earlier in the film, Cliff’s father has threatened to throw the kittens Cliff is keeping as pets into the river, as they cannot afford to keep them: ‘When a thing ain’t wanted, it’s better off dead’, Cliff’s father tells the boy. (Cliff manages to rescue the kittens and leaves them at the gate to the local prison, where one of the wardens appears to take them in.) When Cliff and his father are finally approached by Detective Superintendent Grey (Derek Farr), who has been charged with investigating the case, a traumatised Cliff is huddled in the corner of the makeshift hut that he and his father call home, and he rationalises his actions by quoting his father’s comment about the kittens. Realising that the incident was an accident, and acknowledging the traumatic effect it will have upon Cliff (and his father), Grey notes that ‘If we’re going to start talking about blame, we might as well start with that GI who left that loaded gun about, or the foolish girl who couldn’t make up her mind, or perhaps with the bombs that smashed up so many homes that people like you and Carter have to live in places like this’. ‘What can I do?’ Cliff’s father asks hopelessly, sweeping his small son up in his arms as if he were a rag doll. ‘You can do as all parents ought to do: look after him until he’s old enough to take care of himself’, Grey suggests, unable to help these people any more than he already has. Like many of Comfort’s films, Bang! You’re Dead was originally distributed as the second half of a double-bill. In this instance, the film supported Guy Hamilton’s screen adaptation of J B Priestley’s play An Inspector Calls, starring Alastair Sim. Bang! You’re Dead was cut by the BBFC for its original cinema release in 1954. On this disc, the film runs for 85:01 mins (PAL), plus 30 seconds of footage including the film’s original BBFC certificate and the new Studiocanal logo. The 1954 press release included on this disc as a PDF document cites the film’s running time as 89 minutes – which is most likely the running time of the film after the BBFC cuts. The BFI cites the film as having a length of 7990 feet (88:47 mins), but again this it’s unclear as to whether this is the running time of the film prior to the cuts that were made for its UK release. Nevertheless, accounting for PAL speedup, this is commensurate with the running time of the version of the film contained on this disc

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The print is in good shape, and the monochrome image displays good contrast.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track, which is clean and problem-free. No subtitles are provided.

Extras

The disc includes a stills gallery and the original press release (in PDF format).

Overall

Bang! You’re Dead is a fascinating, haunting little film about the social aftermath of the war. Cliff’s involvement in the death of Jones is upsetting, and the predicament in which he and his lonely father find themselves will haunt the viewer – together with the poverty of the makeshift community in which they live. This disc contains a very good presentation of a film that is little-seen. Some additional contextual material would be more than welcome, but regardless of this, this release comes with a strong recommendation for those interested in British cinema. Bang! You’re Dead is a fascinating, haunting little film about the social aftermath of the war. Cliff’s involvement in the death of Jones is upsetting, and the predicament in which he and his lonely father find themselves will haunt the viewer – together with the poverty of the makeshift community in which they live. This disc contains a very good presentation of a film that is little-seen. Some additional contextual material would be more than welcome, but regardless of this, this release comes with a strong recommendation for those interested in British cinema.

References: McFarlane, Brian, 1999: British Film Makers: Lance Comfort. Manchester University Press For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|