|

|

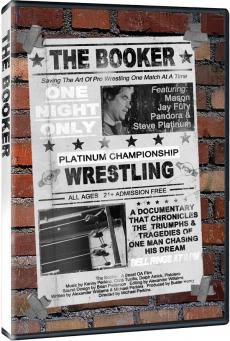

The Booker

R1 - America - IndiePix Films Review written by and copyright: Ethan Stevenson (2nd May 2014). |

|

The Film

I don't particularly care about professional wrestling (or MMA, for that matter, either). It’s not that I explicitly don’t like it. I suppose, push come to shove—or, body slam come to a chair to the back of the head—I'd say I just don’t think about it. Like, at all. I haven't actually seen a match or whatever you call them in a long enough time that it’s almost like I've never seen one at all. Of course, I know who some of the more famous wrestlers of the 80's and 90's are (or were)—because I was that age then, had a television set and a VCR. That kind of pop culture stuff just sort of seeps in, through osmosis; by merely, purely, being. I have vague recollections of something related to the WWF/WWE in the back of my brain, although, if I think about it hard enough, that something was probably only a stupid Hulk Hogan movie. Still—spoiler alert—I can say, unflinchingly, wrestling’s hilariously fake and it always has been. I also seriously doubt anyone, even diehard fans, didn't already know that, deep down, too. Maybe the falseness is the fun? I don't know. And in falseness, as in all things, there are degrees; acceptable hyperboles, within limits. When I read an article on some gossip entertainment website the other day about Hugh Jackman battling a villainous wrestler dressed in a Magneto costume… I was sort of tickled by the total absurdity of what that looked like in pictures (and also, the cringeworthy youtube video). At the same time, even for professional wresting—where characters become villains or victors at a whim, and they have elaborate backstories as dense as any other form of fiction—what’s essentially a really strange promotion for the upcoming “X-Men: Days of Future Past” (2014) seems a bit too showy, doesn’t it? There’s theatricality, yes; and then there’s… whatever Wolverine knocking down a guy in baggy maroon and mauve pyjamas and poorly done up Magneto helmet is. Now I'm not really bothered by a spectator “sport” losing its essence, but in a way I do kind of admire Steve Scarborough, who most certainly didn’t like the smell of what “The Rock” was cookin’, and in his late 30's founded Platinum Championship Wrestling, a “school” located in the American South, centered around teaching techniques that attempt to bring wrestling back to basics. Director Michael Perkins’ “The Booker” is a documentary about Scarborough, his life-long relationship with the sport, and his journey to take a rag tag group of four students meeting in the storage room of a rundown theater to a full-fledged show in front of an audience in a 2,500 seat arena. The documentary’s low budget production values, and stark, low-fi black-and-white visuals are easily forgiven because the rich character arc Perkins chronicles—that is, Scarborough’s identify-defining journey four decades in the making—is kind of fascinating. And his passion, as misplaced as I personally think it may be, is palpable. What makes the film interesting is the borderline deluded but genuine sincerity and conviction with which the man at the center of the picture assures students (and anyone watching voyeuristically through the film) and maybe even himself, that his day will come. With the noblest of intentions, Scarborough argues that—from its origins as a sort of carnival sideshow attraction in the early 20th century—wrestling has always been theater for the masses. He sees each match as a classic, melodramatic morality tale, where characters are “good" or "bad”, not somewhere in the middle; there are clear definitions of what’s “right” and “wrong”; and it always, always, always ends in a cathartic climax with a clear resolution. Of most pertinent interest to Scarborough is what he considers a lack of honor among wrestlers today; that the pros treat everything as too much like a big joke. Scarborough insists that the sport wasn't always quite so absurd. In his mind, modern wrestling has lost what it once was—and it’s audience as well—because the inherent showmanship, the theatricality has increasingly relied on shock, trumped up drama, and gimmicks. It's not at all in the spirit of the pseudo-bloodsport where, yes, there used to be actual blood. Of course, Scarborough has an unique perspective, and a complicated personal history, which is why he thinks the way he does. The long and short of it is, in his youth, Scarborough was surrounded by honorable fighters—he grew up in Hawaii, and in his twenties travelled to Japan to train as a wrestler. Wrestlers are revered in Japan. Their training is brutal, designed to weed out the weak, and those who manage to make it become celebrated professional athletes; they become heroes even. After he returned to the United States, a chance meeting with “Rowdy” Roddy Piper changed Scarborough’s life forever. “Da’Maniac” himself encouraged the wrestler to go into teaching. And so he did, as “Steve Platinum”, a veritable character fit for inside the ring but now resides outside of it, teaching others. Perkins’ documentary—shot over a period of four years—is a portrait of a man with incredible energy, and undeniable enthusiasm. Yet it also depicts a man with a big but easily bruised ego. His self-esteem balloons and deflates with each stressful trial and triumph along the way. Perkins' camera tracks candidly, right along Scarborough through financial troubles, personal foibles, and erratic fits where sometimes he appears impervious to criticism and at other times seems overwhelmed by it. Scarborough’s students also play a large role, each one with an interesting story of their own. (My favorite: a mother who throws into the ring to burn off pent-up rage). The film builds upon the “good” and “bad”, “right” and “wrong” motifs to the sort of suitable climax Scarborough likens to classic theatre. He’s the good, the right, the hero, at least in his head; and wrestling—or, more accurately, what it has become—is the thing that needs to be defeated, to be saved from itself. Curious then that what the documentary doesn’t deliver is a clear, cathartic resolution. It ends, but ambiguously, as though Scarborough’s journey is still far from over, because only he can say when it is.

Video

Shot in black-and-white, on videotape, “The Booker” isn’t quite a looker. Although encoded inside a 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen frame, a majority of the film is presented in 1.33:1 with pillar boxing on the left and right; some of it is postage stamped, both letterboxed and pillar-boxed . There’s nothing specifically problematic with the disc, beyond the usual limitations of the DVD format. The presentation's just not particularly pleasing in the conventional sense. The transfer reflects a low-def source delivered on a low-def format.

Audio

There isn’t much to the film’s English Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo soundtrack either. “The Booker” is a low-fi documentary, both in terms of visuals and sound design. Still, the track does a decent job delivering dialogue, and offers support to the voiceover and Scarborough’s manic monologuing without any serious issue. No subtitles are included.

Extras

Pre-menu bonus trailers for two other documentaries are the only extras: - “Hori Smoku Sailor Jerry” (1.78:1, anamorphic widescreen; 1 minute 19 seconds). - “The Nine Lives of Marion Barry” (1.33:1; 2 minutes 22 seconds).

Overall

The low budget production values and stark, low-fi black-and-white visuals of “The Booker” are easily forgiven because the rich character at the center of the picture, "Platinum” Steve Scarborough, is such an enthusiastic, egotistical enigma. The merits of professional wrestling and it’s history are secondary to me, although they might prove more interesting for actual fans of the “sport”. Certainly worth a look.

|

|||||

|