|

|

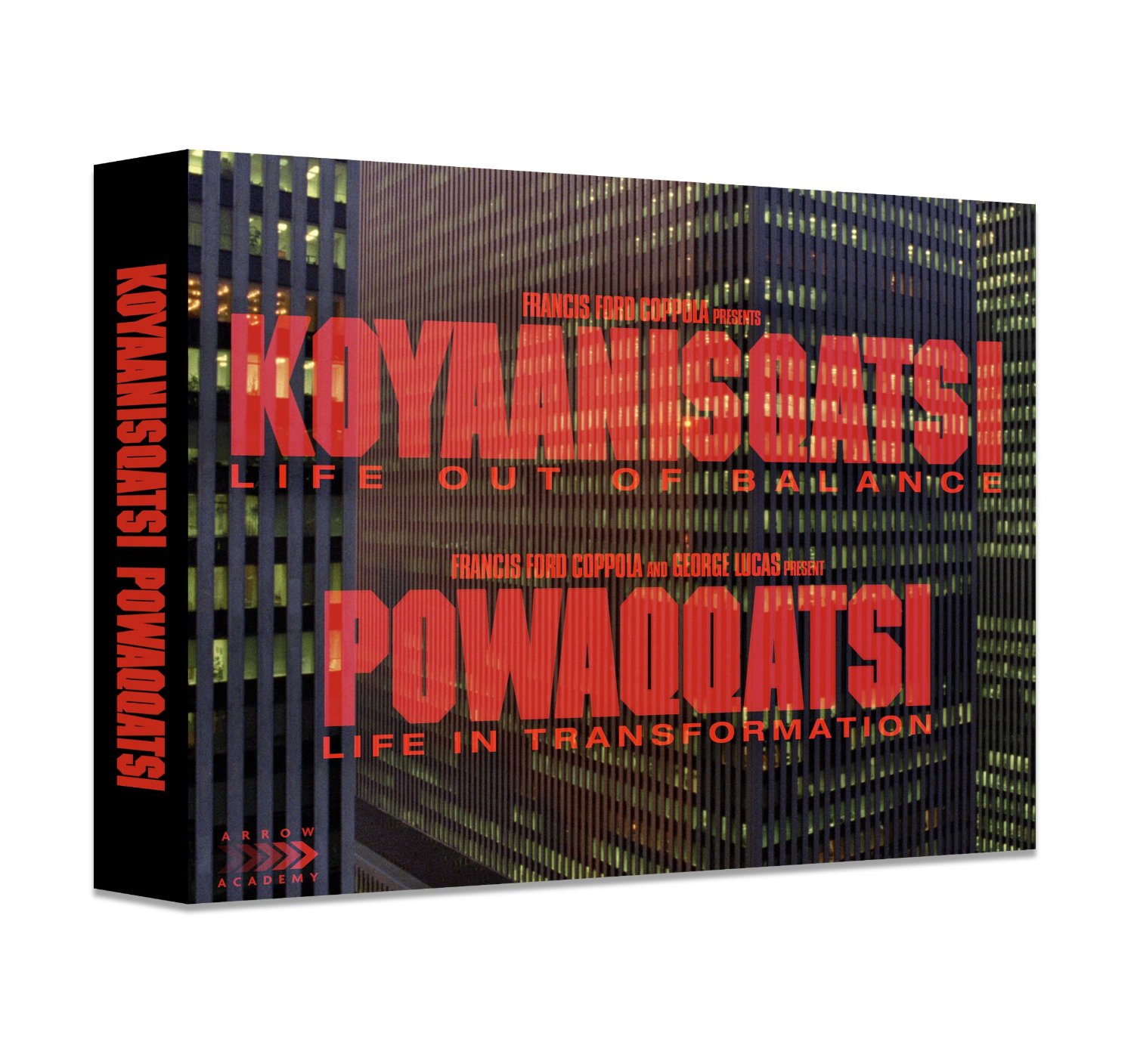

Koyaanisqatsi (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th May 2014). |

|

The Film

Koyaanisqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1982) Please note that this film is part of a boxed set that also includes Reggio’s Powaqqatsi, reviewed here.  ‘These films are meant to provoke […] to offer an experience, rather than an idea or information or a story about a knowable or a fictional subject’, Reggio says in the featurette included on this disc. The films are intended to offer their audience different ‘ways in’ and not to impose one single reading on their viewers: Reggio states (in the ‘Essence of Life’ featurette) that ‘For some people [Koyaanisqatsi is] an environmental film, for some people it’s an ode to technology, for some people it’s a piece of shit’. ‘These films are meant to provoke […] to offer an experience, rather than an idea or information or a story about a knowable or a fictional subject’, Reggio says in the featurette included on this disc. The films are intended to offer their audience different ‘ways in’ and not to impose one single reading on their viewers: Reggio states (in the ‘Essence of Life’ featurette) that ‘For some people [Koyaanisqatsi is] an environmental film, for some people it’s an ode to technology, for some people it’s a piece of shit’.

Koyaanisqatsi – the title of which, as any film fan knows, originates in the Hopi word for ‘life out of balance’ – offers a poetic series of images, accompanied by Phillip Glass’ haunting minimalist music, which juxtapose scenes of nature with montages depicting human society and technology: Reggio asserts that ‘the main event today is not seen by those who live in it [….] the transiting from old nature, or the natural environment […] into a technological milieu’. We don’t use technology, Reggio tells us: ‘We live technology’. By stripping away narrative and character, Reggio hoped to focus on this issue. Some elements of the film refer to recognisable genres: in some sequences set in Las Vegas and New York, Reggio offers what are essentially street portraits of Americans as they pass by the camera, presented in protracted slow-motion that emphasises their reactions to the camera. Some of them become aware of the camera; others appear to remain oblivious to it – or unaffected by it. Some of these people perform for the camera, happy for attention to be directed their way; others scowl questioningly. To some extent, these images recall the combative street portraiture of the New York-based Magnum photographer Bruce Gilden.  In many ways, Koyaanisqatsi resembles ‘city symphony’ films of the 1920s and 1930s such as Manhatta (Paul Strand & Charles Sheeler, 1921) and Walter Ruttman’s Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grossstadt (1927). These films offered poetic images of the urban environment, focusing on patterns of behaviour and the relationships between people and the environment in which they lived and worked. Reggio’s poetic approach is familiar from these early examples of ‘city symphony’ films, but his techniques are somewhat different: Reggio uses time-lapse photography to show groups of people en masse, machinery whirring away (for example, in sequences depicting the production of Twinkies) and vehicles throbbing through city streets; and he contrasts this time-lapse imagery with the slow-motion techniques that he uses for the ‘street portraits’ cited in the paragraph above. Masses of people in Grand Central Station are thus contrasted with individuals – but strangely, as with Gilden’s street portraiture, the subjects are dehumanised by this method, made to seem animalistic. The majority of the subjects appear dissatisfied, angry or sad. Many of them are elderly. In one of the film’s most haunting images, the hand of an elderly hospital patient reaches out desperately from a gurney (in close-up which, from the flattening of perspective, is apparently shot with a long telephoto lens); fortunately, after a protracted wait it is met with the feminine hand of a hospital worker. In many ways, Koyaanisqatsi resembles ‘city symphony’ films of the 1920s and 1930s such as Manhatta (Paul Strand & Charles Sheeler, 1921) and Walter Ruttman’s Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grossstadt (1927). These films offered poetic images of the urban environment, focusing on patterns of behaviour and the relationships between people and the environment in which they lived and worked. Reggio’s poetic approach is familiar from these early examples of ‘city symphony’ films, but his techniques are somewhat different: Reggio uses time-lapse photography to show groups of people en masse, machinery whirring away (for example, in sequences depicting the production of Twinkies) and vehicles throbbing through city streets; and he contrasts this time-lapse imagery with the slow-motion techniques that he uses for the ‘street portraits’ cited in the paragraph above. Masses of people in Grand Central Station are thus contrasted with individuals – but strangely, as with Gilden’s street portraiture, the subjects are dehumanised by this method, made to seem animalistic. The majority of the subjects appear dissatisfied, angry or sad. Many of them are elderly. In one of the film’s most haunting images, the hand of an elderly hospital patient reaches out desperately from a gurney (in close-up which, from the flattening of perspective, is apparently shot with a long telephoto lens); fortunately, after a protracted wait it is met with the feminine hand of a hospital worker.

The images and music are repetitious, as Gary Tarn notes in his introduction to the film, but this repetition is (to use the word Tarn uses to describe it) analogue in nature. Each bar in Glass’ music may repeat a motif heard before, but it is not identical to what has gone before it – unlike the use of sampling in dance music, for example. Likewise, the photography emphasises patterns: time lapse photography shows queues of people forming and swarming, like ants, at the bottom of an escalator in Grand Central Station; or vehicles moving through traffic, their headlights making visual patterns and emphasising the regularity and repetition within their movements. However, as with the music, this repetition of imagery is ‘analogue’: patterns emerge, but each action that is repeated is not identical to that which has gone before it – the time lapse sequences are not on a loop. Ultimately, for Reggio the urban sprawl is comparable with a circuit board: shots of freeways at night, lit up by the headlights of cars filmed in time lapse, and aerial shots of the city at night segue into shots of circuit boards. Life in these environments is a ‘grid’, Reggio seems to be saying, predicated on conformity and hive behaviours in which people seem to move as if in a trance, enthralled by and in service to ‘the machine’. The film runs for 86:08 mins.

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film was shot in a mixture of 16mm and 35mm film, with some sequences (notably the explosion of the Atlas-Centaur rocker over Cape Canaveral at the film's climax) also seemingly offering optical zooms into 35mm footage. The differences in texture between these types of footage is readily apparent in this HD presentation, which is testament to the natural-looking, organic transfer (there is no ugly, overzealous noise reduction here) and the strong encode. Colour consistency is remarkable, as evident from the vivid red of the main title. The image is rich in detail and texture.

Audio

Two audio options are present: a LPCM 2.0 stereo mix, and a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 channel. Both are perfectly acceptable. The 5.1 mix offers a strong, immersive soundscape – even for an audio purist, this offers an excellent remix. The stereo track is equally strong, though a little less immersive.

Extras

Introduction by Gary Tarn (3:39). Tarn notes that cinema is alchemical: ‘sometimes images and sound can come together to create something greater than the sum of its parts’. Koyaanisqatsi is, for him, ‘pure’ cinema, comprised of just images and music, ‘stripped of narrative and character and action, leaving each viewer to interpret the film in his own way’. Thus, Tarn argues, the film ‘feels different in each viewing’. ‘Essence of Life’ featurette (25:08). In this featurette, Reggio and Glass are interviewed about both films, and especially about Koyaanisqatsi. Reggio reflects on his experiences with the Christian Brothers and how this helped to shape his worldview as a filmmaker, and he talks about his work with the IRE. He also talks about Bunuel’s Los olvidados, which gave Reggio ‘a spiritual experience’ and helped to shape his own work. Glass notes that at the time Reggio approached him, he didn’t write ‘movie music’; though of course, Glass has since then become strongly associated with film scoring. Theatrical trailer (2:23)

Overall

Koyaanisqatsi is visually remarkable, and accompanied by some excellent music by Phillip Glass. However, even today it’s a hugely divisive film – which, if Reggio is to be believed, is part of the ‘point’ of the picture. The film emphasises the ‘hive’ dynamic of life in developed countries. The pleasures of the film are, to some extent, the pleasures of the flaneur, the ‘people watcher’. In the 1858 publication Ce qu’on voit dans les rues de Paris, the journalist Victor Fournel once noted that the flaneur, people watcher or ‘urban observer’ is like a ‘walking daguerreotype’ recording ‘the bustle of the city, the multifarious physiognomy of the public mind… the loves and hates of the crowd’ (quoted in Smith: 79). These are the impulses that drive, for example, much of street photography – and to some extent, the imagery in Koyaanisqatsi offers a kind of moving street photography: the (arguably invasive) street portraiture of Bruce Gilden, the depictions of urban labour in the work of Lewis Hine. This disc, part of a set which also includes the ‘sequel’, Powaqqatsi, contains an excellent presentation of the film and some good contextual material. It’s Marmite viewing, and has divided audiences since its first release, but this Blu-ray offers a superb way to watch the film (and learn a little more about it). References: Smith, Paul, 1998: ‘“La Peintre de la vie moderne” and “La Peinture de la vie ancienne”’. In: Hobbs, Richard (ed), 1998: Impressions of French Modernity: Art and Literature in France, 1850-1900. Manchester University Press: 76-98

|

|||||

|