|

|

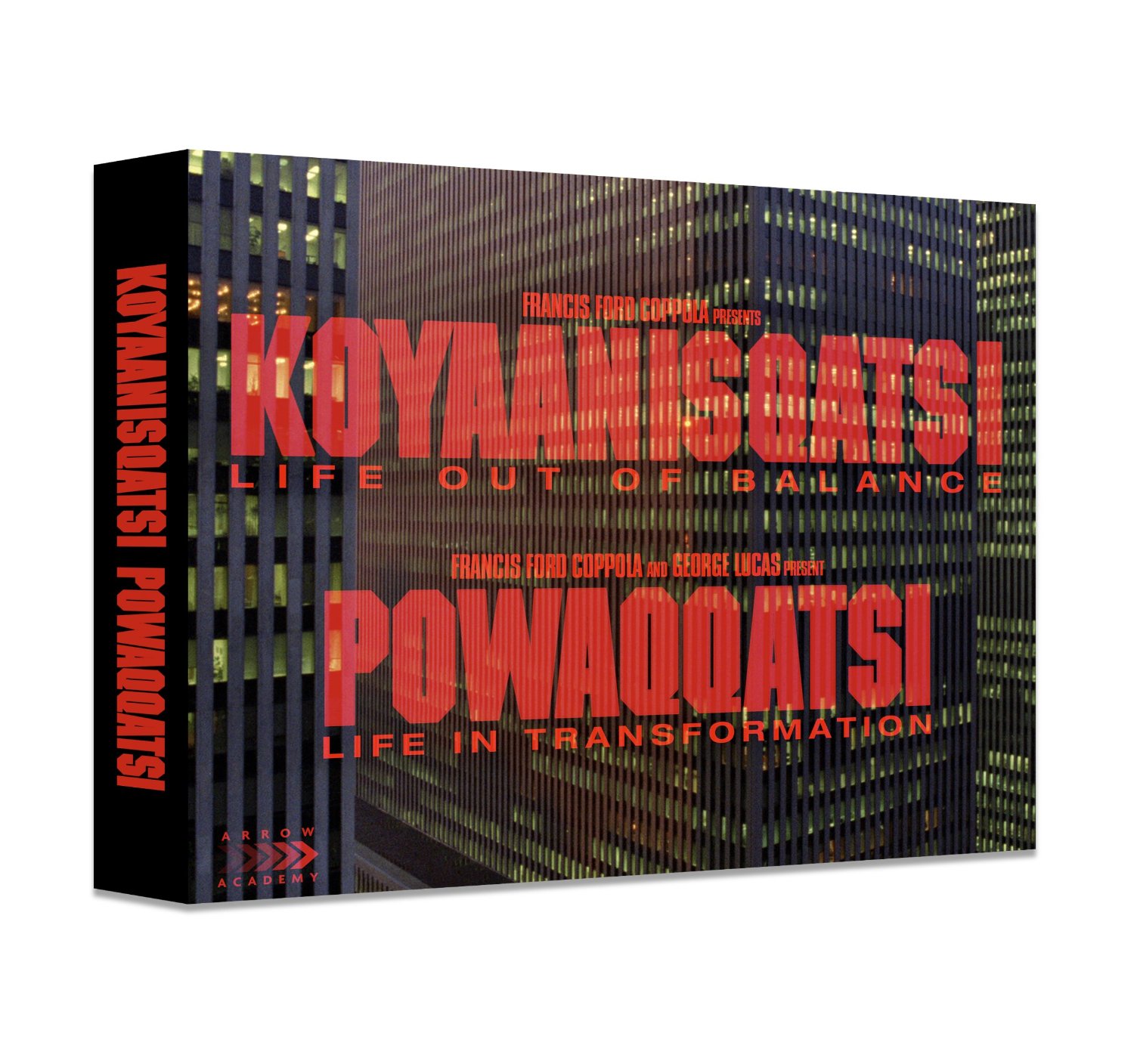

Powaqqatsi (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th May 2014). |

|

The Film

Powaqqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1988) Please note that this film is part of a boxed set that also includes Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi, reviewed here. A sequel of sorts to Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Godfrey Reggio’s non-narrative examination of the impact of technology, Powaqqatsi sees Reggio shifting focus onto life in least developed countries (Peru, Kenya, Nepal, India Brazil, Egypt). The film shares some similarities with its predecessor, but also contains some notable differences. ‘In this film, the aural presence is co-equal with the image’, Reggio asserts in ‘Impact of Progress’, the featurette included on this Blu-ray release. Composer Phillip Glass was involved throughout the film, rather than (as with Koyaanisqatsi) developing his score for the picture in post-production. With Powaqqatsi, Glass recorded his music before some scenes were even shot: the music was provided to the film’s cinematographer (Leonidas Zourdoumis), who would listen to the music on a Walkman whilst shooting the picture. ‘It’s like a hand-in-glove operation, it’s one medium motivating the other’, Reggio claims in relation to this methodology. Reggio’s approach has always been somewhat contradictory, inasmuch as he asserts that the films mean different things to different people, and the audience may interpret them in any way they like, but he also imposes a reading onto the film: Powaqqatsi, he tells us in ‘Impact of Progress’, is predicated on the notion that life in the Southern Hemisphere is being eroded by a form of cultural and technological homogenisation, which offers a threat to these more ‘natural’ ways of life (to use Reggio’s phraseology). Reggio likens the film to an ‘attempt at the hour of death’ to rise above yourself ‘and to see yourself in context. And this context is the technological order’. For Reggio, Koyaanisqatsi was about the Northern Hemisphere, whereas Powaqqatsi focuses on the Southern Hemisphere, which ‘is being consumed by the norms of progress and development’.  Powaqqatsi certainly foregrounds the human subject in a more direct way than Koyaanisqatsi: the images in Powaqqatsi nearly all contain human figures. The opening sequence focuses on the workers in the Brazilian gold mine at Serra Pelada, as they carry bags filled with dirt three hundred feet up a hillside. Glass’ music here is urgent; the images are presented in slow-motion. One of the miners, who was apparently struck on the head by an object falling from the top of the mine, is carried, unconscious, by his colleagues to safety. His body, as he is carried, is in a cruciform pose, recalling the Pietà of Christian iconography. Zourdoumis’ camera picks out the bodies covered in mud, the telephoto lens flattening perspective and making the workers appear as if they are the parts of a jigsaw puzzle, an undulating mass of mud-soaked bodies as they climb the wet, slippery hillside. The imagery can’t help to recall in the viewer’s mind the myth of Sisyphus and his endless task. Throughout the film, people are shown working together, toiling and aiding one another. Powaqqatsi certainly foregrounds the human subject in a more direct way than Koyaanisqatsi: the images in Powaqqatsi nearly all contain human figures. The opening sequence focuses on the workers in the Brazilian gold mine at Serra Pelada, as they carry bags filled with dirt three hundred feet up a hillside. Glass’ music here is urgent; the images are presented in slow-motion. One of the miners, who was apparently struck on the head by an object falling from the top of the mine, is carried, unconscious, by his colleagues to safety. His body, as he is carried, is in a cruciform pose, recalling the Pietà of Christian iconography. Zourdoumis’ camera picks out the bodies covered in mud, the telephoto lens flattening perspective and making the workers appear as if they are the parts of a jigsaw puzzle, an undulating mass of mud-soaked bodies as they climb the wet, slippery hillside. The imagery can’t help to recall in the viewer’s mind the myth of Sisyphus and his endless task. Throughout the film, people are shown working together, toiling and aiding one another.

In his review of the film for New York Magazine, David Denby notes that Reggio ‘disdains narration and explanatory titles’, also noting that Reggo does not ‘allow any of the workers to say what it feels like to stand in muck day after day. Instead, he presses the workers into a languorous tableau. The Ecstasy of Physical Labor, it might be called’ (1988: 110). In contrast with the city workers in Koyaanisqatsi, whose actions were made faster by the use of time lapse photography (thus emphasising their hive-like behaviours), the workers in the least developed countries depicted within Powaqqatsi are shown toiling in slow motion, giving them a dignity and grace lacked by their First World counterparts. Furthermore, some commentators have highlighted Reggio’s supposed fetishisation of the bodies of these workers in least developed countries with the ‘original cinematic fascination with studying the motions of the exotic that motivated Luca Comerio and, before him, the photographer Eadweard Muybridge (MacDonald, 1993: 137). For this reason (and others), Reggio was accused of ‘making a virtue of poverty, of romanticising poverty and oppression’ – a criticism he rejects vehemently (see the comments by Reggio in ‘Impact of Progress’). The film runs for 99:41 mins.

Video

Shot entirely on 35mm, Powaqqatsi has a more consistent aesthetic than Koyaanisqatsi, which was assembled from 35mm and 16mm footage. The 1080p presentation of Powaqqatsi on this disc, in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio and using the AVC code, is superb. The rich images are presented here with clarity and a strong level of detail. Colour consistency and contrast are excellent. The film also has an unfiltered and organic appearance, with a natural grain structure as befits a film shot on 35mm.

Audio

There are two audio options: a 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio track; and a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Both of these are problem-free. The 5.1 remix offers a deeply immersive experience, Glass’ music filling the soundscape. The LPCM 2.0 stereo track is equally good.

Extras

‘Impact of Progress’ featurette (19:56) This featurette features Reggio and Glass discussing the film. They talk about Reggio’s approach and the necessity to use ‘high technology’ to get his message across: ‘I don’t think it’s […] contradictory to use the very medium you are questioning’, he says, ‘because it is the medium that can reveal the subject the most clearly. In a way, if you want to use a metaphor, it’s like using fire on fire. It’s like walking a razor’s edge; it’s this and that, rather than joining the purity league – “Oh, it must be this way, and if it’s not, you’re the Devil” [….] Life is not that way; life is more complex; it’s a mixture of all of this, and that’. Reggio talks about the impact of technology: ‘The computer, not being a sign, is the most powerful instrument in the world, in that it produces what it signifies, it produces this globalization. In that sense it is the highest magic in the world, and something that we are all in adoration of. And that’s what these films are about’. He talks about the title of the film, alluding to a ‘black magician’ that devours another’s life force through seduction. Reggio also talks at some length about Naqoyqatsi, the third film in the series. Short film: ‘Anima Mundi’ (29:05). This 1992 collaboration between Reggio and Glass was made to accompany the World Wildlife Fund’s inception of the Convention for Biological Diversity (created at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro). Unlike Koyaanisqatsi and Powaqqatsi, this film focuses on the animal kingdom. It’s an excellent little film. Theatrical Trailer (2:05)

Overall

Rituals are central to Powaqqatsi, both the rituals of labour and the rituals of faith: early in the film, we are shown a montage of images from within a Buddhist temple, and Powaqqatsi ends with an arrangement of a portion of the Muslim call to prayer. Powaqqatsi certainly has its share of striking imagery: an enormous freight train that tears past the camera seemingly endlessly; a shot of a burnt-out car by the roadside, placed in the centre of the composition, as ghost-like cars drift past it. Reggio rejects claims that Powaqqatsi romanticises life in least developed countries, but those criticisms of the film certainly hold water. Denby (op cit.) compares the film to Edward Steichen’s famous 1955 photography exhibition ‘The Family of Man’, suggesting that Reggio ‘has become a Third World chauvinist’ (110). Reggio’s use of slow-motion photography in this film offers the workers in these less industrialised nations a sense of dignity that isn’t afforded their First World counterparts in Koyaanisqatsi: although Reggio’s intent may be to offer a film that is open to interpretation, there is clear evidence of a (subconscious?) editorial instinct at play in these films. (Reggio ‘confesses’ in the ‘Impact of Progress’ that he restaged one of the film’s most famous images, that of a young boy walking by a roadside becoming enveloped in a cloud of dust thrown up by a passing lorry, an image which speaks of the resilience of individuals in these less industrialised societies.) Rituals are central to Powaqqatsi, both the rituals of labour and the rituals of faith: early in the film, we are shown a montage of images from within a Buddhist temple, and Powaqqatsi ends with an arrangement of a portion of the Muslim call to prayer. Powaqqatsi certainly has its share of striking imagery: an enormous freight train that tears past the camera seemingly endlessly; a shot of a burnt-out car by the roadside, placed in the centre of the composition, as ghost-like cars drift past it. Reggio rejects claims that Powaqqatsi romanticises life in least developed countries, but those criticisms of the film certainly hold water. Denby (op cit.) compares the film to Edward Steichen’s famous 1955 photography exhibition ‘The Family of Man’, suggesting that Reggio ‘has become a Third World chauvinist’ (110). Reggio’s use of slow-motion photography in this film offers the workers in these less industrialised nations a sense of dignity that isn’t afforded their First World counterparts in Koyaanisqatsi: although Reggio’s intent may be to offer a film that is open to interpretation, there is clear evidence of a (subconscious?) editorial instinct at play in these films. (Reggio ‘confesses’ in the ‘Impact of Progress’ that he restaged one of the film’s most famous images, that of a young boy walking by a roadside becoming enveloped in a cloud of dust thrown up by a passing lorry, an image which speaks of the resilience of individuals in these less industrialised societies.)

As noted above, the fact that this film was wholly shot on 35mm (whereas, by comparison, Koyaanisqatsi was shot on a mixture of 16mm and 35mm) means that Powaqqatsi has a more cohesive aesthetic than its predecessor. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is very good, and there is also some strong contextual material. This boxed set is a very pleasing release and comes with a strong recommendation. References: Denby, David, 1988: ‘We Are the Third World’. New York Magazine (16 May, 1988): 110-1 MacDonald, Scott, 1993: Avant-Garde Film: Motion Studies. Cambridge University Press

|

|||||

|