|

|

It Happened in Paris

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (29th May 2014). |

|

The Film

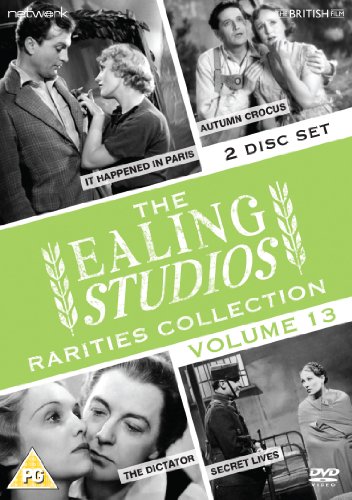

This film has been released as part of Network’s Ealing Studios Rarities Collection, Vol 13. It Happened in Paris (Robert Wyler, 1935)  After directing some scenes for Autumn Crocus (1934), also included in this DVD set, Carol Reed was allowed to share directing duties with Robert Wyler on It Happened in Paris. Based on his work on this picture, Reed was then offered his first solo directing credit, the adaptation of Frederick Marryat’s 1836 novel Midshipman Easy (1935). After directing some scenes for Autumn Crocus (1934), also included in this DVD set, Carol Reed was allowed to share directing duties with Robert Wyler on It Happened in Paris. Based on his work on this picture, Reed was then offered his first solo directing credit, the adaptation of Frederick Marryat’s 1836 novel Midshipman Easy (1935).

It Happened in Paris is based on Yves Mirande’s French play L’Arpete, and this adaptation was written by John Huston. A romantic comedy, the film focuses on Jacqueline (Nancy Burne), a young woman who aspires to be ‘the most famous [fashion] designer in Paris’, and American artist Paul Jones (John Loder), who arrives in Paris seeking ‘inspiration’. Jones rents a studio flat, in a building inhabited completely by starving artists, opposite Jacqueline’s flat. After a mix-up involving a pair of Jacqueline’s bloomers (strangely enough, misunderstandings about ‘knickerbockers’ also crop up in Autumn Crocus), Paul and Jacqueline meet. After an initially spiky introduction, they begin to fall in love; Jacqueline becomes Paul’s muse. However, Paul struggles to sell his artwork, and Jacqueline bribes an art dealer into buying one of Paul’s paintings, in order to boost his confidence in his creative talents. The art dealer selects a painting of Jacqueline that Paul has produced for himself. Paul is initially reluctant to sell the painting, but Jacqueline persuades him to. Things become more complicated when, during a party that Paul throws to celebrate the fact that he has sold one of his paintings, an older man turns up at the flat. The man is the American millionaire John V R Knight; Paul is in fact his son, who made the decision to ‘slum it’ as a struggling artist in Paris under an assumed name. Jacqueline is distinctly unimpressed, especially when it is revealed that Paul’s father intends him to marry a wealthy woman from his own society. (‘I don’t approve of international marriages anyways’, John Knight tells Jacqueline.) Paul leaves Paris and preparations are made for him to marry; in the meantime, Jacqueline finds work as a fashion designer and becomes increasingly important in that role, to the extent that she is (unknowingly) hired to provide the outfits for Paul’s impending wedding. For me at least, it’s hard to watch films that feature a wandering ‘artist’ who attaches himself to the continental Bohemian lifestyle (or a ‘slumming’ artist who is attracted to poverty) without thinking of Tony Hancock’s satirical depiction of such types in The Rebel (Robert Day, 1961) or perhaps even the lyrics to Pulp’s ‘Common People’. The trope has been satirised and deconstructed so much since the 1930s that it is difficult to take seriously. Thankfully, this film has a light touch and a strong sense of humour – although there are some fairly dark scenes (in one sequence, Jacqueline’s employer essentially tries to prostitute her to a wealthy client; Jacqueline, of course, refuses). The film is uncut and runs for 66:21 mins (PAL). Unlike the other films in this set, which open with the StudioCanal logo, It Happened in Paris opens with the BFI logo. Autumn Crocus (Basil Dean, 1934)  Based on a play by Dodie Smith, Autumn Crocus was directed by Basil Dean, with some scenes handled by Carol Reed – in his first taste of film directing. The film is notable as one of the final screen roles of Ivor Novello, who struggled to adapt his screen persona to the age of talking pictures. Lawrence Napper and Michael Williams argue that by this stage in his career, Novello was arguably ‘a pastiche of himself […] endowed with a wonderful pan-European accent and clad in lederhosen’ (Napper & Williams, 2001: 53-4). However, in this film, Napper & Williams argue, Novello is stripped of the ‘kind of sexual frisson’ with which he had been associated in some of his silent films (ibid.: 54). The film has been dismissed as ‘embarrassing’, with one vintage review stating that ‘Novello’s schoolboy knees under his Tyrolean shorts make the audience, if not the players, feel bashful’ (quoted in Macnab, 2000: 50). Shortly after this film, Novello would retire from screen acting completely. Based on a play by Dodie Smith, Autumn Crocus was directed by Basil Dean, with some scenes handled by Carol Reed – in his first taste of film directing. The film is notable as one of the final screen roles of Ivor Novello, who struggled to adapt his screen persona to the age of talking pictures. Lawrence Napper and Michael Williams argue that by this stage in his career, Novello was arguably ‘a pastiche of himself […] endowed with a wonderful pan-European accent and clad in lederhosen’ (Napper & Williams, 2001: 53-4). However, in this film, Napper & Williams argue, Novello is stripped of the ‘kind of sexual frisson’ with which he had been associated in some of his silent films (ibid.: 54). The film has been dismissed as ‘embarrassing’, with one vintage review stating that ‘Novello’s schoolboy knees under his Tyrolean shorts make the audience, if not the players, feel bashful’ (quoted in Macnab, 2000: 50). Shortly after this film, Novello would retire from screen acting completely.

Autumn Crocus opens in a schoolroom in which a class full of young girls are singing. It’s raining outside. Above the desk of the teacher, Jenny Grey (Fay Compton), is a landscape painting of the Tyrolean mountains. It’s the end of term, and Jenny and her friend and colleague Edith (Esme Church) are planning on spending their holiday in Venice. However, on the way to Venice, Jenny wishes to visit the Austrian Tyrol. Edith resists at first, but Jenny soon persuades her that it is a good idea. When they arrive at their hotel, presided over by the charismatic and joyful Andreas Steiner (Ivor Novello), Edith is put off by the fact that all of the hotel’s guests must eat at the same table (‘Oh, I hate eating in herds’, she complains). However, Steiner persuades her that her stay at his hotel will be a happy one. Also at the hotel are a young couple, Alaric (a very young Jack Hawkins) and Audrey (Diana Beaumont), who live together without being married: ‘We are two conscientious young people living together for scientific reasons’, Alaric announces. Jenny and Edith have arrived in the little Tyrolean village in time for the national festival, a time of singing and joy. Against this romantic backdrop, Jenny begins to fall in love with their host, Steiner; she is 34 and considers herself to be an aging spinster, so she tells him that she is 29. However, they are fully aware of their different backgrounds. Jenny tells Steiner that she was born in Manchester. Steiner, who has visited England before, tells her, ‘I did not see it [the city] when I was there’. Jenny informs him, ‘You wouldn’t like it. It’s where all the factories are’. However, Jenny is sensitive to her age. When Steiner tells her, ‘You are like something in a fairy tale’, she responds: ‘I’m too old to be in a fairy tale’. On her last morning in the village, Jenny sneaks out early to climb one of the mountains. She is met by Steiner. However, Jenny’s romantic illusions are shattered when she discovers that Steiner is married, and his wife is the cook at the hotel. Steiner also has a young daughter, the little girl Jenny has seen around the hotel. Steiner declares his love for Jenny, and she asks if he will divorce his wife. ‘There is no divorce in our church’, he tells her, before attempting to persuade Jenny to be his mistress: ‘My wife, need she ever know? [….] What I ask of you is perhaps wrong but it is life. And I do not think it is wrong: it’s too beautiful. What does it matter if we love each other?’ Steiner tells Jenny that she should return to the village once a year, so that they may conduct their affair that way. Autumn Crocus is clearly intended to be a romantic drama, but, perhaps owing to changing cultural attitudes since the film’s release, Steiner’s attempts to woo Jenny (despite the fact that he is married) come across as more than a little creepy. He reminds her of her age (continually telling her that one day, she will be old, and towards the end of the film referring to her as ‘the flower of spring that blooms in autumn’), essentially preying on her negative self-esteem, before attempting to persuade her to become his mistress once a year. The film focuses largely on the etiquette of sexuality, with the sexual habits of Europeans depicted as exotic and alien: not only does Steiner offer his bizarre proposition to Jenny, but Alaric and Audrey astonish the other guests with the confession that they are ‘living in sin’ – but ‘for scientific reasons’. Thankfully, Edith is there to provide the voice of reason, reminding Jenny that the affair that Steiner proposes is morally wrong. ‘You make it [sound] all ugly and sordid’, Jenny tells her friend. ‘It is sordid’, Edith reminds her: ‘Have you thought about what it is, stealing another woman’s husband?’ Jenny relents, agreeing to return home, never to return to the Austrian Tyrol after her brief encounter there. ‘Oh, my dear, will you never grow up?’, Edith asks Jenny. ‘No. Only old’, Jenny laments. The film ends as it began, in Jenny’s classroom in Manchester, rain pouring outside the window and the painting of the Tyrolean mountains on the classroom wall above Jenny’s desk. The film is uncut and runs for 80:40 mins (PAL). The Dictator (Loves of a Dictator, For the Love of a Queen, The Love Affair of the Dictator) (Victor Saville, 1935)  Beginning in Copenhagen in 1766, with the marriage of Christian VII (Emlyn Williams) of Denmark and Caroline Matilda (Madeleine Carroll) – the sister of the King of England, George II – The Dictator tells the story of the relationship between the unhappy Queen Caroline Matilda and the royal physician, Johann Friedrich Struensee (Clive Brook). The film focuses on the period of Struensee’s rise to power as royal adviser (a title he was awarded in 1770), during which time Struensee, acting with the presumed authority of the mentally unstable Christian VII, initiated a series of reforms including the abolition of torture, restructuring of the military, the abolition of censorship, taxation of gambling and several attempts to quell political corruption. After reputedly fathering the second child of Queen Caroline Matilda in 1794, Princess Louise Auguste (who was often referred to as ‘la petite Struensee’), Struensee was eventually arrested and executed for usurpation of royal authority: he was executed (beheaded, then drawn and quartered) on the 28th of April, 1772. Beginning in Copenhagen in 1766, with the marriage of Christian VII (Emlyn Williams) of Denmark and Caroline Matilda (Madeleine Carroll) – the sister of the King of England, George II – The Dictator tells the story of the relationship between the unhappy Queen Caroline Matilda and the royal physician, Johann Friedrich Struensee (Clive Brook). The film focuses on the period of Struensee’s rise to power as royal adviser (a title he was awarded in 1770), during which time Struensee, acting with the presumed authority of the mentally unstable Christian VII, initiated a series of reforms including the abolition of torture, restructuring of the military, the abolition of censorship, taxation of gambling and several attempts to quell political corruption. After reputedly fathering the second child of Queen Caroline Matilda in 1794, Princess Louise Auguste (who was often referred to as ‘la petite Struensee’), Struensee was eventually arrested and executed for usurpation of royal authority: he was executed (beheaded, then drawn and quartered) on the 28th of April, 1772.

The story has formed the basis of a number of films: firstly, Ludwig Wolff’s 1923 picture Die Liebe einer Konigin (‘The Loves of a King’); then The Dictator; the 1957 German film Herrscher ohne Krone, (‘Ruler Without Crown’) directed by Harald Braun; Henrik Kolind’s 2010 Danish film Caroline: Den Sidste Rejse (‘Caroline: The Last Trip’); and, most recently, Nikolaj Arcel’s En kongelig affaere, which achieved notable success outside Denmark (including a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at the 85th Academy Awards) when it was released under the title A Royal Affair. This version of the story begins with the immediate build-up to the royal wedding, to which Caroline Matilda is clearly resistant (‘Why did they send me here?’, she asks). The marriage is being conducted to enable a greater alliance between Denmark and England. However, Caroline Matilda establishes, in a perhaps surprisingly frank manner, her distaste at the idea of sleeping with Christian VII: ‘I’ll share his throne at twenty four hours notice, if he likes’, she says; ‘but I’m only human, and I refuse to share… anything else’. (The pregnant pause before the phrase ‘anything else’ is all-telling.) Meanwhile, Christian VII, who in this film is depicted as a petulant child (it wouldn’t be surprising if Emlyn Williams’ performance in this role has had some influence on the character of King Joffrey in HBO’s current series Game of Thrones, 2011- ), complains that he really wanted to marry Caroline Matilda’s sister, moaning that Caroline Matilda ‘called me a spoilt young puppy who wants a good smacking’. Often known as the ‘mad king of Denmark’, Christian VII was a known alcoholic who had little to no self-restraint. The film depicts Christian VII as a less-than-fully-functioning adult: at the start of the film, the state is in effect run by his stepmother, the former Queen of Denmark Juliana Maria (Helen Haye). During a night of debauchery in a brothel, where he naively believes his identity to be disguised, Christian VII collapses. Dr Struensee is called to attend to him: although Struensee is not told that it his patient is the king, Struensee clearly surmises this. Struensee takes advantage of the fact that he has not been told that the drunken lecher who he must revive is Christian VII, and wakens the lecherous lout by throwing him in a tub of cool water before referring addressing him as a ‘young ruffian’. However, rather than take offense at this, Christian VII praises Struensee’s actions: the physician is the only person who does not patronise the king. ‘You’ll run your own life instead of letting others run it for you’, Struensee advises Christian VII: ‘Wine is the water of Beelzebub, and women can drag a man from the gates of Heaven itself and drive him to the everlasting depths of Purgatory’. Taking note of Struensee’s advice, Christian VII comments, ‘You know, he’s [Struensee is] the first man who ever told me the truth’, and he offers Struensee a place in his court. At the king’s court, Struensee meets Queen Caroline Matilda. Initially, he tells her that she should try to put her ‘petty quarrels’ with the king aside, for the benefit of Danish society (‘wearing a crown no longer turns a woman into a great queen’, he reminds her). However, over time their relationship becomes increasingly romantic. Meanwhile, Struensee demonstrates his skills at diplomacy by quelling a rebellion, vowing that as ‘the world can only find its salvation in self-respect’, he must attempt to ‘change the face of Denmark’. Made the Count of Artenberg, Struensee becomes increasingly influential in both Danish political life and the bedroom of Queen Caroline Matilda. Victor Saville took over the directing of The Dictator one week into production, after the original director, Alfred Santel, had been removed from the film once the producers decided Santel was ‘a good director, but historical drama was not his line of country’ (2000: 84). In fact, Saville began working on The Dictator on Wednesday, 10 October, 1934, less than a day after completing work on The Iron Duke (Victor Saville, 1934); James Chapman asserts that this highlights Saville’s role as a ‘hired hand’ (2005: 334). Saville was hired at the request of the film’s stars, Clive Brook and Madeline Carroll; for both of these actors, The Dictator was the first film they made upon their return to England after becoming Hollywood stars (Saville, op cit.: 84). The producer of The Dictator was Ludovic Toplitz, an Italian banker. Toplitz had entered filmmaking by helping to finance The Private Life of Henry VIII (Alexander Korda, 1933). The Dictator was attractive to Toplitz because it offered another the chance to make another historical drama which may potentially have the same level of success as The Private Life of Henry VIII. However, Saville notes in his autobiography that ‘I have to confess that the subject had little interest for me but the high quality of production that Toplitz aimed for compensated for my lack of enthusiasm for the story’ (ibid.). Saville’s claimed lack of interest in the story is underscored by an amusing anecdote which he relates in his autobiography: Saville claims that forty years after making The Dictator, he ‘read a biography on Caroline, Queen of Denmark, and I thought what an interesting film this would have made in the days when the cinema bought historical drama. It was only after I finished the book that I realized I had made the subject in 1934’ (ibid.). In America, the film was given the more salacious title The Loves of a Dictator, and cuts were made, at the request of Joseph Breen, to ‘the entire close shot of the Queen on her bed; the dialogue at the council table in regard to the heir to the throne; the scene in the tavern with a woman on the King’s lap; the doctor kissing the girl; the Queen Mother’s dialogue in the council chamber; over-exposure of the Queen’s breasts; the Queen’s visit to Struensee’s room; the King’s discussion of his wife’s adultery; and [the use of the word] “damn” throughout’ (Slide, 1998: 57). The film runs for 82:22 mins (PAL). The film was cut by the BBFC when it was released in 1935, but details of the cuts made to the film are unavailable. It’s unclear whether this release contains the version of the film as cut by the BBFC in 1935, or if it is uncut. Secret Lives (I Married a Spy) (Edmond Greville, 1937)  Based on a novel by Paul De Sainte Colombe, this film begins with the outbreak of the First World War: the opening title card announces that ‘This story opens in Paris on the first day of August 1914, and is based on the actual life of a young woman during the Great War’. Based on a novel by Paul De Sainte Colombe, this film begins with the outbreak of the First World War: the opening title card announces that ‘This story opens in Paris on the first day of August 1914, and is based on the actual life of a young woman during the Great War’.

The young woman in question is 22 year old Lena Schmidt (Brigitte Horney), the daughter of German-born baker Ben Schmidt (Ben Field). With the announcement of the war with Germany, Lena and Ben find their bakery assailed by ‘panic buyers’ who, in a fit of pique, accuse Ben and Lena of being German spies. Ben’s German heritage casts suspicion upon both him and his daughter, and the pair are held in a concentration camp for German immigrants and suspected collaborators. ‘How long do we have to stay here?’, Lena asks one of the guards. ‘Oh, not very long. Only until the war is over’, is the response she receives. Lena manages to escape from the concentration camp after arranging a liaison with a lecherous guard, during which she manages to wrest control of his gun. Outside the camp, Lena is approached by a man she had seen during her incarceration, the French secret service chief (Frederick Lloyd), who tells her, ‘I like your determination. You could be very useful to France [….] You have two assets: perfect German, and no relations’: her father, Ben, has died whilst detained in the camp. Lena is then enlisted as a spy against the Germans. A ‘marriage of convenience’ is arranged, to make her a French citizen (and prevent her from being deported to Germany). However, even after working as a spy for France, Lena finds that she struggles to escape from the stigma that has been attached to her. The Variety review stated that the film ‘tries to go arty in a continental way, but doesn’t make the grade, either in acting, direction or photography’ (quoted in Mavis, 2011: np). Certainly, there is some interesting expressionistic photography by the Czech cinematographer Otto Heller, who would later shoot films such as The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955), Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960) and The IPCRESS File (Sidney J Furie, 1966). The opening sequence of Secret Lives begins with a pan down from the crucifix on the wall of Lena’s bedroom (symbolic of the ‘old’ way of morality that is abandoned with the outbreak of war) to Lena, asleep on her bed. It’s not a stretch to suggest that this foreshadows the way in which, later in the film, Lena will be required to sleep with various men in order to, firstly, escape from the concentration camp and, later, perform her work as a spy. In the early scene in which the Schmidt’s bakery is invaded by angry Parisian women, the faces of the women who begin to smash glass and steal loaves of bread are shown in an expressionistic montage of tight close-ups which make them appear as if they were pecking hens. In another sequence, Lena is shown laying in bed after being detained in the concentration camp, a thunderstorm raging outside. Lena’s head is framed by darkness, the reflections of rain on the windowpane above her bed reflected onto her face. Later sequences make strong use of chiaroscuro lighting and canted angles. In fact, the visual style of this film is very reminiscent of some of the more expressively photographed films noirs that would be produced in the next decade (for example, Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity, 1944). More of a study of the plight of Lena Schmidt than a film about spycraft, Secret Lives found some controversy in the US when it was released there. Several sequences were cut for the American release, including some of the footage detailing Lena’s life in the concentration camp (depictions of her with ‘inadequate clothing’) and the ‘implication that she had slept with a German spy’ (Slide, 1998: 176-7). Furthermore, the Production Code Authority received a letter of complaint about the film from the French Embassy: it’s fair to say that, given the bind in which Lena finds herself in this film, and the downbeat way in which it resolves itself, the film is less than flattering in its depiction of French society. The film was cut by the BBFC on its original release, but details of the cuts are not available. This version of the film runs for 78:30 mins (PAL); it’s unclear whether this DVD is uncut or contains the original version of the film as cut by the BBFC in 1937.

Video

All of the films are presented in their original Academy aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The films are all monochrome. The Dictator has a clear presentation; the image is slightly soft, but this is most likely owing to the lenses used to photograph the picture. On all four films, contrast levels are good, with strong tonality. Secret Lives, the most recent of the films, has very strong mid-tones and some deep, rich shadows. Most of the films are pretty clear of debris, although It Happened in Paris and Autumn Crocus exhibit the most wear and tear – admittedly, very minor, but noticeable throughout.

Audio

All of the films are presented with dual mono tracks. These are audible throughout. The audio track on Autumn Crocus has some background hiss that becomes more noticeable towards the end of the film, and occasionally buries the dialogue. The track on It Happened in Paris is hollow and tinny, although no better or worse than the majority of films of a similar vintage. Secret Lives and The Dictator have the most ‘clean’ audio track. Sadly, none of the films contain subtitles.

Extras

The disc contents are as follows: DISC ONE: It Happened in Paris (Robert Wyler, 1935) (66:21) Autumn Crocus (Basil Dean, 1934) (80:40) Gallery (1:55) DISC TWO: The Dictator (Victor Saville, 1935) (82:22) Secret Lives (Edmond T Greville, 1937) (78:30) DVD-ROM content (all as ‘PDF’ files): ‘Autumn Crocus’ Lyric Theatre programme ‘Secret Lives’ pressbook ‘Secret Lives’ shooting script (under the title ‘No Escape’) The gallery on disc one contains promotional images and press cuttings from all four of the films.

Overall

Yet another interesting package from Network’s Ealing Studios Rarities series, Volume 13 contains some a diverse group of films. Secret Lives is arguable the best out of the four, though it wasn’t well-received on its initial release: there is some great expressionistic photography, and the narrative is strong too. Autumn Crocus is perhaps the odd one out: its exploration of the ‘exotic’ sexuality of continentals and Steiner’s attempts to seduce Jenny are dated and slightly unsettling. Yet another interesting package from Network’s Ealing Studios Rarities series, Volume 13 contains some a diverse group of films. Secret Lives is arguable the best out of the four, though it wasn’t well-received on its initial release: there is some great expressionistic photography, and the narrative is strong too. Autumn Crocus is perhaps the odd one out: its exploration of the ‘exotic’ sexuality of continentals and Steiner’s attempts to seduce Jenny are dated and slightly unsettling.

References: Chapman, James, 2005: Past & Present: National Identity in British Film. London: I B Tauris Macnab, Geoffrey, 2000: Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screen Acting in British Cinema. London: Bloomsbury Mavis, Paul, 2011: The Espionage Filmography. London: McFarland Napper, Lawrence & Williams, Michael, 2001: ‘The curious appeal of Ivor Novello’. In: Babington, Bruce (ed), 2001: British Stars and Stardom: From Alma Taylor to Sean Conner. Manchester University Press: 42-55 Saville, Victor, 2000: Evergreen: Victor Saville in His Own Words. Southern Illinois University Press Slide, Anthony, 1998: Banned in the USA: British Films in the United States and Their Censorship, 1933-1966. London: I B Tauris This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|