|

|

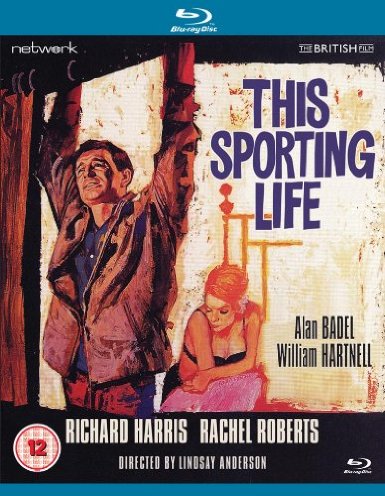

This Sporting Life (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (6th June 2014). |

|

The Film

This Sporting Life (Lindsay Anderson, 1963)  Produced by Karel Reisz and directed by Lindsay Anderson, This Sporting Life (1963) appeared at the tail end of the British ‘new wave’ and its exploration of social realism (or ‘kitchen sink realism’). Anderson began his career as a film critic, writing for the magazines Sequence and Sight & Sound. He also co-founded (with Karel Reisz, Lorenza Mazzetti and Tony Richardson) the Free Cinema movement, which aimed to stimulate the ‘free’ production of films outside the conventional film industry, offering both narrative and technical innovation, and focusing on a humanistic view of life in Britain away from London. However, Anderson resisted the application of the label ‘movement’ to Free Cinema, as ‘it [Free Cinema] had little or no theoretical base’ (Aitken, 2001: 151). Susan Hayward notes that Free Cinema ‘was not a case of a movement but a sharing of common ideals where cinema was concerned’ (2013: 164). Produced by Karel Reisz and directed by Lindsay Anderson, This Sporting Life (1963) appeared at the tail end of the British ‘new wave’ and its exploration of social realism (or ‘kitchen sink realism’). Anderson began his career as a film critic, writing for the magazines Sequence and Sight & Sound. He also co-founded (with Karel Reisz, Lorenza Mazzetti and Tony Richardson) the Free Cinema movement, which aimed to stimulate the ‘free’ production of films outside the conventional film industry, offering both narrative and technical innovation, and focusing on a humanistic view of life in Britain away from London. However, Anderson resisted the application of the label ‘movement’ to Free Cinema, as ‘it [Free Cinema] had little or no theoretical base’ (Aitken, 2001: 151). Susan Hayward notes that Free Cinema ‘was not a case of a movement but a sharing of common ideals where cinema was concerned’ (2013: 164).

Under the Free Cinema banner, Anderson directed a number of short documentary features, including the acclaimed ‘Thursday’s Children’ (1953), which focused on the work of the Royal School for the Deaf in Margate. In 1954, ‘Thursday’s Children’ won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Subject, and Anderson continued to make short documentaries until 1959 when he retreated into the world of theatre, directing performances of such plays as Willis Hall’s The Long and the Short and the Tall. Anderson’s retrenchment into theatre occurred just as his fellow Free Cinema filmmakers Tony Richardson and Karel Reisz began to define British ‘new wave’ cinema (and its focus on disaffected and anti-establishment ‘angry young man’ protagonists, and its emphasis on social realism) with their adaptations of, respectively, John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger (Tony Richardson, 1959) and Alan Sillitoe’s novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Karel Reisz, 1960). Although through his association with the Free Cinema movement, Anderson had done much to consolidate the conventions of the later British ‘new wave’ cinema, This Sporting Life was the first feature film that Anderson directed. The film was adapted from the novel by David Storey and was set in Wakefield in West Yorkshire, where Anderson’s last four documentaries had been made. Like many of the British ‘new wave’ films, This Sporting Life focuses on an archetypal ‘angry young man’, Frank Machin (Richard Harris). The narrative is presented through a non-linear structure, beginning with a rugby match in which Machin, the star player of the Wakefield Trinity Rugby League team, is badly injured. The accident requires six of Machin’s front teeth to be removed; as he drifts in and out of consciousness following the blow to the head, and as the dentist places him under anaesthetic during an emergency procedure to remove his teeth, Machin experiences flashbacks to his life prior to becoming a local celebrity.  Before being taken on by the Rugby League club, Machin worked as a miner and lodged with Margaret Hammond (Rachel Roberts) and her two young children. Mrs Hammond is a repressed, life-rejecting widow whose husband Eric died in an industrial accident with a lathe, which Machin is later told was really an act of suicide. Thrown together, these two lonely people develop an ambiguous relationship. Machin is besotted with Mrs Hammond, but although she seems to be attracted to him, she refuses to acknowledge her feelings for him and is often repelled by his brutish, animalistic nature. When Frank is offered the chance at being recruited into Wakefield’s Rugby League team, by a scout (‘Dad’ Johnson, played by William Hartnell) with a curious interest in Machin, Machin sees this as an opportunity to escape his dreary and insular life. He’s an aggressive player, which at least initially is felt to be a strength by one of the club’s managers, Mr Weaver (Alan Badel). However, Mr Slomer (Arthur Lowe), the club’s chairman who has a more ‘old school’ approach to the sport, has doubts about Machin. Before being taken on by the Rugby League club, Machin worked as a miner and lodged with Margaret Hammond (Rachel Roberts) and her two young children. Mrs Hammond is a repressed, life-rejecting widow whose husband Eric died in an industrial accident with a lathe, which Machin is later told was really an act of suicide. Thrown together, these two lonely people develop an ambiguous relationship. Machin is besotted with Mrs Hammond, but although she seems to be attracted to him, she refuses to acknowledge her feelings for him and is often repelled by his brutish, animalistic nature. When Frank is offered the chance at being recruited into Wakefield’s Rugby League team, by a scout (‘Dad’ Johnson, played by William Hartnell) with a curious interest in Machin, Machin sees this as an opportunity to escape his dreary and insular life. He’s an aggressive player, which at least initially is felt to be a strength by one of the club’s managers, Mr Weaver (Alan Badel). However, Mr Slomer (Arthur Lowe), the club’s chairman who has a more ‘old school’ approach to the sport, has doubts about Machin.

Machin discovers that the dream of sport as means of escaping from the exploitation inherent within working-class life is a myth: within the rugby team, he finds that he is once again exploited by the club’s middle-class owners and also by their wives. Mrs Weaver (Vanda Goodsell) calls Machin to her home with the intention of seducing him, and after the conflicted Machin storms out of the Weaver’s house, he discovers that Weaver’s attitude towards him has changed: Weaver now wants Machin out of the team. Slomer, on the other hand, senses that Machin has been manipulated by Weaver’s wife and her tendency to ‘indulg[e] in what I call Mrs Weaver’s weakness for social informalities’ and offers himself as a new ally to Machin. However, Machin comes to realise that regardless of his newfound celebrity, his position will always be at the bottom of the scrum. Frank also begins a relationship of sorts with Margaret, but this rapidly deteriorates and leads the film towards an unavoidably tragic conclusion. Anderson imposes a non-linear structure on the film which, at the time of its initial release, drew comparisons with the French New Wave filmmakers; Anderson’s film was compared specifically to Alain Resnais’ disorienting L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad, 1961). This Sporting Life begins on the rugby field, where Frank is injured; his front teeth broken, Frank is taken to an out-of-hours dentist and put under anaesthetic, and for much of the film Anderson uses parallel editing as Frank remembers how he became involved in rugby and his combative relationship with Margaret. However, although the flashback structure led critics to assert that Anderson’s film had been heavily shaped by Resnais, in actuality This Sporting Life’s non-linear structure was already present in Storey’s novel (see Walker, 1974: 173).  At the centre of the narrative is Frank’s aggressive nature, and from the outset this aggression is signalled both visually and aurally. The film begins with an abstract, discordant main title theme (composed by Roberto Gerhard) that is interrupted by sounds of a crowd of spectators cheering encouragement as the opening titles play out – plain white text on a black screen. The chanting is threatening and primal, and these crowd noises appear at various points throughout the film, underpinning scenes of Frank’s rage and aggression. Following the main titles, the film opens with a rugby game which sets the tone for the scenes of the sport that we see throughout the film: a player lands near the ball and a boot enters the frame, kicking the ball away. The sound of the boot hitting the ball booms on the soundtrack like a gunshot; the boot barely misses the other player’s face. The game is presented in a montage of violent close-ups of collisions, and the scrum is represented through a series of very tight shots of the participants struggling against one another. When Frank is injured by one of the members of the opposing team, he is carried off the field and the crowd’s chants segue into the sound of a heavy industrial drill; as Frank walks towards the camera Anderson dissolves to a close-up of a large mining drill (wielded by Frank) biting into the earth, an echo of his past as a miner, the life from which he escaped into rugby. This is the beginning of Frank’s memories about his association with the sport of rugby, and in the sequences which deploy parallel editing, cutting between the past and the present, Anderson frequently uses overlapping sounds as a bridge between one scene and the next, as if Frank’s memories are triggered by the association of certain sounds with memories of the past. This expressionistic use of sound as a means of carrying the audience in to the internal state of the protagonist works in a similar way to the use of sound in Martin Scorsese’s boxing movie Raging Bull (1980) - notably during the sequence depicting the final fight between Sugar Ray Robinson (Johnny Barnes) and Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro). At the centre of the narrative is Frank’s aggressive nature, and from the outset this aggression is signalled both visually and aurally. The film begins with an abstract, discordant main title theme (composed by Roberto Gerhard) that is interrupted by sounds of a crowd of spectators cheering encouragement as the opening titles play out – plain white text on a black screen. The chanting is threatening and primal, and these crowd noises appear at various points throughout the film, underpinning scenes of Frank’s rage and aggression. Following the main titles, the film opens with a rugby game which sets the tone for the scenes of the sport that we see throughout the film: a player lands near the ball and a boot enters the frame, kicking the ball away. The sound of the boot hitting the ball booms on the soundtrack like a gunshot; the boot barely misses the other player’s face. The game is presented in a montage of violent close-ups of collisions, and the scrum is represented through a series of very tight shots of the participants struggling against one another. When Frank is injured by one of the members of the opposing team, he is carried off the field and the crowd’s chants segue into the sound of a heavy industrial drill; as Frank walks towards the camera Anderson dissolves to a close-up of a large mining drill (wielded by Frank) biting into the earth, an echo of his past as a miner, the life from which he escaped into rugby. This is the beginning of Frank’s memories about his association with the sport of rugby, and in the sequences which deploy parallel editing, cutting between the past and the present, Anderson frequently uses overlapping sounds as a bridge between one scene and the next, as if Frank’s memories are triggered by the association of certain sounds with memories of the past. This expressionistic use of sound as a means of carrying the audience in to the internal state of the protagonist works in a similar way to the use of sound in Martin Scorsese’s boxing movie Raging Bull (1980) - notably during the sequence depicting the final fight between Sugar Ray Robinson (Johnny Barnes) and Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro).

Throughout This Sporting Life, Frank’s rage is emphasised, and Harris plays this aspect of the character splendidly. Frank’s tendency to act like a predator in prowling through scenes is underscored by the other characters within the film: at one point, Mrs Weaver declares that Frank is ‘like a big cat’ who ‘never stop[s] moving’. In an early sequence, Frank prowls around a night club before starting a fight with the captain of the team for no apparent reason other than to assert his ‘alpha male’ status, and later in the film he brutally twists the arm of the elderly ‘Dad’ Johnson in order to get information out of him. (Johnson responds by saying ‘You get far too excited, lad’.) Many of Harris’ lines are spat through clenched teeth, and the character of Frank lives by a solipsistic philosophy of self-reliance: when Margaret tells him ‘Some people have life made for them’, Frank responds by angrily declaring that ‘That’s right, Mrs Hammond, and some people make it for themselves’. Later, he tells Mrs Weaver that ‘It’s like this, Mrs Weaver: you see something, and you go out and you get it. It’s as simple as that’. The only outlet for Frank’s rage and aggression is on the rugby field and, more subtly, through his combative interactions with Margaret. However, Frank’s aggression is tempered by scenes which show his tenderness in dealing with children, whether those children are Mrs Hammond’s or simply a group of youngsters who crowd around Frank in order to get his autograph after a match. According to Anderson, Frank has ‘an ambiguity of nature, half overbearing, half acutely sensitive, that fascinated me without my being fully aware that I understood him. The same was true of his tortured, impossible relationship with the woman in the story, a bleak northern affair of powerful, inarticulate emotions frustrated or deformed by Puritanism or inhibition. Their background was rough and hard, no room here for charm or sentimental proletarianism’ (Anderson, quoted in Walker, 1974: 174).  The relationship between Frank and Margaret is fraught with violence and verbal sparring, owing to Frank’s inability to express his love in a tender way and Margaret’s repressed sexuality: in his 1974 book Hollywood England, Alexander Walker suggests that the story is ‘one of self-punishment, of masochistically “missed connections” in which the male partner can’t embody his love in tenderness, and the female one won’t accept the pleasure of her own repressed sexuality’ (Walker, 1974: 174). It is this troubled relationship between Frank and Margaret that is at the centre of the film: for Alexander Walker, the film’s ‘subject was working-class: but what it illuminated was the emotional space inside its characters, not the industrial landscape around them’ (ibid.: 169). In this way, the film differs from many of the other films within the British ‘new wave’, and one of the ways in which This Sporting Life pulls its focus in to the ‘emotional space’ inside Frank is through its use of parallel editing and its expressionistic use of sound, as outlined above. The relationship between Frank and Margaret is fraught with violence and verbal sparring, owing to Frank’s inability to express his love in a tender way and Margaret’s repressed sexuality: in his 1974 book Hollywood England, Alexander Walker suggests that the story is ‘one of self-punishment, of masochistically “missed connections” in which the male partner can’t embody his love in tenderness, and the female one won’t accept the pleasure of her own repressed sexuality’ (Walker, 1974: 174). It is this troubled relationship between Frank and Margaret that is at the centre of the film: for Alexander Walker, the film’s ‘subject was working-class: but what it illuminated was the emotional space inside its characters, not the industrial landscape around them’ (ibid.: 169). In this way, the film differs from many of the other films within the British ‘new wave’, and one of the ways in which This Sporting Life pulls its focus in to the ‘emotional space’ inside Frank is through its use of parallel editing and its expressionistic use of sound, as outlined above.

Both fiercely independent (at one point, Margaret tells Frank, ‘If I’m left alone, I’m happy’), Frank and Margaret orbit one another throughout the film, and their interactions occasionally explode into conflict. When Frank reveals to Margaret that he has been given a thousand pounds to play for the rugby club, Margaret reminds him that the money he has been given is more than the money she received when her husband died. Later, Frank takes Margaret to dinner in an upmarket restaurant, where Frank demonstrates a lack of proper etiquette: when the waiter asks Frank if he wants anything to drink and Frank replies that he does, the waiter offers to send the wine waiter over, and Frank asks him ‘Well, what the bloody hell did you ask me for?’ At the end of the meal, Margaret asserts that Frank is ‘act[ing] like a pig’, and Frank responds by gesturing to the other customers in the restaurant, stating that ‘Well, if I’m a pig, what’s this load of fat bastards, then?’ Margaret is depicted as a self-denying widow, and in one scene Frank forces himself onto her in a moment that would later cause problems for the British censors. (As Frank holds Margaret down on the bed in his room, she protests and tries to break free, muttering ambiguously, ‘You’re a man. You’re a bleedin’ man’.) The director of the BBFC, John Trevelyan, found this specific scene, which he interpreted as a depiction of a rape, to be problematic, and in the censor’s list of ‘cautions’ prepared before the film went into production Trevelyan claimed that the script was characterised by ‘a “feel” of violence’ (Trevelyan, quoted in Walker, 1974: 176). Trevelyan also expressed disapproval at the ‘bad’ language within the film, claiming that even ‘for an X. film there are limits to what we would accept and we think that this script goes beyond them’ (ibid.). The censor also objected to the suggestion of male nudity in the scenes set in the changing rooms.  The changing room scenes highlight an ambiguity within the film surrounding Frank’s sexuality. The club’s scout ‘Dad’ Johnson is subtly coded as gay; his interest in Machin is suggested by Margaret to be an erotic fascination. One evening, Margaret notes to Frank that ‘The old man [Johnson] treats you like a son’. Frank resists this interpretation of his relationship with the club’s scout, telling her, ‘I call him “Dad” because he’s old’. ‘I don’t mean that’, Margaret responds: ‘He looks at you like a girl’. ‘Now, don’t come at that’, Frank answers her angrily, clearly comprehending that she is insinuating that Johnson is gay: ‘He’s interested, that’s all’. To this, Margaret notes dryly, ‘I’d say excited’. ‘What do you mean, excited?’, Frank asks, ‘He hasn’t got much to get excited about at his age’. Margaret notes the softness of Johnson’s hands, taking this as an index of the feminine aspects of his character: ‘He’s never had a job of work in his life’, she tells Frank, ‘Just look at his hands. He’s got awful hands: they’re all soft’. After Machin has been signed by the club for a thousand pounds, Weaver drives Frank home in Weaver’s Bentley. On the way there, Weaver jokes with Frank, describing him as ‘property of the city’. Laughing at this, Weaver places a hand on Frank’s knee. Anderson cuts to the gesture in close-up, allowing it to linger in the audience’s mind, and then cuts to Frank reacting to it, a quizzical expression playing over his face. The viewer is left to ask whether Weaver’s gesture is an act that symbolises his ownership of Frank, or if it is a sexual advance. (The involvement of Weaver in his wife’s later attempt to seduce Frank is left ambiguous: when Weaver punishes Frank after he turns down Mrs Weaver’s proposal, it’s unclear whether this is because Weaver is angry over his wife’s sexual interest in Frank, or if Weaver takes joy in being cuckolded and his anger has therefore been piqued by Frank’s rejection of Mrs Weaver.) The various scenes in the team’s locker room feature an abundance of male nudity. The men are shown cavorting with one another, naked, in their communal bath. Machin is shown in the bath with another player, both of them naked, Frank forcing the neck of his teammates’ bottle of beer into his mouth. Another man, Ken Wade (Harry Markham), tells them, ‘Come on, you two fairies. Let’s have you out of here’. In response, Frank jokes, ‘Why don’t you come in, Ken? Let’s have a look and see what you’ve got’. In the context of the film’s fairly open (given the era) depiction of Johnson’s homosexuality, the phallic symbolism within the bathing scene is difficult to ignore. The changing room scenes highlight an ambiguity within the film surrounding Frank’s sexuality. The club’s scout ‘Dad’ Johnson is subtly coded as gay; his interest in Machin is suggested by Margaret to be an erotic fascination. One evening, Margaret notes to Frank that ‘The old man [Johnson] treats you like a son’. Frank resists this interpretation of his relationship with the club’s scout, telling her, ‘I call him “Dad” because he’s old’. ‘I don’t mean that’, Margaret responds: ‘He looks at you like a girl’. ‘Now, don’t come at that’, Frank answers her angrily, clearly comprehending that she is insinuating that Johnson is gay: ‘He’s interested, that’s all’. To this, Margaret notes dryly, ‘I’d say excited’. ‘What do you mean, excited?’, Frank asks, ‘He hasn’t got much to get excited about at his age’. Margaret notes the softness of Johnson’s hands, taking this as an index of the feminine aspects of his character: ‘He’s never had a job of work in his life’, she tells Frank, ‘Just look at his hands. He’s got awful hands: they’re all soft’. After Machin has been signed by the club for a thousand pounds, Weaver drives Frank home in Weaver’s Bentley. On the way there, Weaver jokes with Frank, describing him as ‘property of the city’. Laughing at this, Weaver places a hand on Frank’s knee. Anderson cuts to the gesture in close-up, allowing it to linger in the audience’s mind, and then cuts to Frank reacting to it, a quizzical expression playing over his face. The viewer is left to ask whether Weaver’s gesture is an act that symbolises his ownership of Frank, or if it is a sexual advance. (The involvement of Weaver in his wife’s later attempt to seduce Frank is left ambiguous: when Weaver punishes Frank after he turns down Mrs Weaver’s proposal, it’s unclear whether this is because Weaver is angry over his wife’s sexual interest in Frank, or if Weaver takes joy in being cuckolded and his anger has therefore been piqued by Frank’s rejection of Mrs Weaver.) The various scenes in the team’s locker room feature an abundance of male nudity. The men are shown cavorting with one another, naked, in their communal bath. Machin is shown in the bath with another player, both of them naked, Frank forcing the neck of his teammates’ bottle of beer into his mouth. Another man, Ken Wade (Harry Markham), tells them, ‘Come on, you two fairies. Let’s have you out of here’. In response, Frank jokes, ‘Why don’t you come in, Ken? Let’s have a look and see what you’ve got’. In the context of the film’s fairly open (given the era) depiction of Johnson’s homosexuality, the phallic symbolism within the bathing scene is difficult to ignore.

Frank asserts his contempt for the people who allow themselves to be exploited and repressed, but ironically he allows himself to be exploited by the bourgeois Weaver and Slomer. After his teeth have been broken, he is taken to the dentist. Weaver waits outside. Frank sits in the chair whilst the dentist argues over the payment for his services (ten guineas). ‘It’s no party here. Let’s get on with it’, Frank complains helplessly: ‘Come on, whatever the bloody price’. When Margaret declares to Frank that ‘They all laugh at you and point you out. Didn’t you know that? Trying to be different’, Frank responds by angrily stating that ‘You want me to be like them. You want me to crawl about just like the rest. Well, just have a look at the rest [….] Take a good look at the bloody people around you. There isn’t a bleedin’ man amongst them: you’re flat on your back from the go, crawling about you. Because they haven’t got the guts. Do you understand that? They haven’t got the guts to stand up and walk about like me’. However, Frank eventually comes to realise that he is no better off within the rugby team than he was when he was working as a miner: the sport offers a sense of freedom that is illusory and is as much based on inequality, class prejudice and exploitation as Frank’s previous job as a miner. Frank asserts his contempt for the people who allow themselves to be exploited and repressed, but ironically he allows himself to be exploited by the bourgeois Weaver and Slomer. After his teeth have been broken, he is taken to the dentist. Weaver waits outside. Frank sits in the chair whilst the dentist argues over the payment for his services (ten guineas). ‘It’s no party here. Let’s get on with it’, Frank complains helplessly: ‘Come on, whatever the bloody price’. When Margaret declares to Frank that ‘They all laugh at you and point you out. Didn’t you know that? Trying to be different’, Frank responds by angrily stating that ‘You want me to be like them. You want me to crawl about just like the rest. Well, just have a look at the rest [….] Take a good look at the bloody people around you. There isn’t a bleedin’ man amongst them: you’re flat on your back from the go, crawling about you. Because they haven’t got the guts. Do you understand that? They haven’t got the guts to stand up and walk about like me’. However, Frank eventually comes to realise that he is no better off within the rugby team than he was when he was working as a miner: the sport offers a sense of freedom that is illusory and is as much based on inequality, class prejudice and exploitation as Frank’s previous job as a miner.

This Sporting Life was one of the last of the British ‘new wave’ films; the distributors, the Rank Organisation, struggled to determine how to market the film, especially due to its bleak and oppressive tone. As Walker asserts, the film is ‘puritan in the self-denying English tradition, yet romantic in the self-destructive Byronic one’ (ibid.: 169) and this proved a hard formula for the distributors to market. Although the film is one of the most fondly-remembered (and atypical) of the British ‘new wave’ pictures of the early 1960s, at the time of its release it was not a commercial success. However, for a fan of British cinema it is a must-watch, thanks to Anderson's almost abstract approach to the subject matter and a dynamite performance by Richard Harris. The film runs for 134:09 minutes.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. This is a superb presentation. The monochrome image is excellent, filled with detail. Contrast is good: the mid-tones are rich, and there is plenty of visual information present in the shadows and highlights. The print is clean: there are some vertical lines (notoriously difficult to remove) that are present here and there. The film shows a natural grain structure: there is no overt evidence of overzealous noise reduction or sharpening. Please note that the images used in this review are for illustration purposes only and do not reflect the quality of the transfer on Network’s Blu-ray disc.

Audio

Audio is a little disappointing. The only audio option is a lossy Dolby Digital two-channel mono track. This is clear and audible but, because it’s lossy, lacks range – although the opening sound of the boot hitting the ball has some ‘bite’, it would have been nice to see a lossless audio option on this disc. Optional English subtitles are provided.

Extras

Trailer (2:20, HD) Galleries: - Production Image Gallery (10:40, SD) - Behind the Scenes Image Gallery (2:29, SD) - Portrait Image Gallery (2:06, SD) - Promotional Image Gallery (0:47, SD)

Overall

This Sporting Life was a difficult film to sell on its initial release: much longer than most of the other films from the British new wave, its bleak worldview must have alienated many viewers on its initial release. However, the years have been kind to the film, and repeated viewings give it added complexity, especially within the context of some of the films that Anderson directed after this one: there are faces familiar from later Anderson films (Arthur Lowe, Leonard Rossiter), and the film’s subtle exploration of homosexuality as a non-issue is ahead of its time. In retrospect, the film seems to owe a great deal to Elia Kazan’s adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), especially in terms of Harris’ Brando-esque portrayal of Frank Machin. This Sporting Life is a complex, gripping example of the ‘kitchen sink’ drama. This Sporting Life was a difficult film to sell on its initial release: much longer than most of the other films from the British new wave, its bleak worldview must have alienated many viewers on its initial release. However, the years have been kind to the film, and repeated viewings give it added complexity, especially within the context of some of the films that Anderson directed after this one: there are faces familiar from later Anderson films (Arthur Lowe, Leonard Rossiter), and the film’s subtle exploration of homosexuality as a non-issue is ahead of its time. In retrospect, the film seems to owe a great deal to Elia Kazan’s adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), especially in terms of Harris’ Brando-esque portrayal of Frank Machin. This Sporting Life is a complex, gripping example of the ‘kitchen sink’ drama.

This Blu-ray contains a superb presentation of the film, although it’s a shame the disc only contains a lossy audio option. Nevertheless, visually the upgrade to HD is impressive and more than enough to justify upgrading to this Blu-ray release. References: Aitken, Ian, 2001: European Film Theory and Cinema: An Introduction. Indiana University Press Hayward, Susan, 2013: Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge (Fourth Edition) Walker, Alexander, 1974: Hollywood England: The British Film Industry in the Sixties. London: Orion This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|