|

The Film

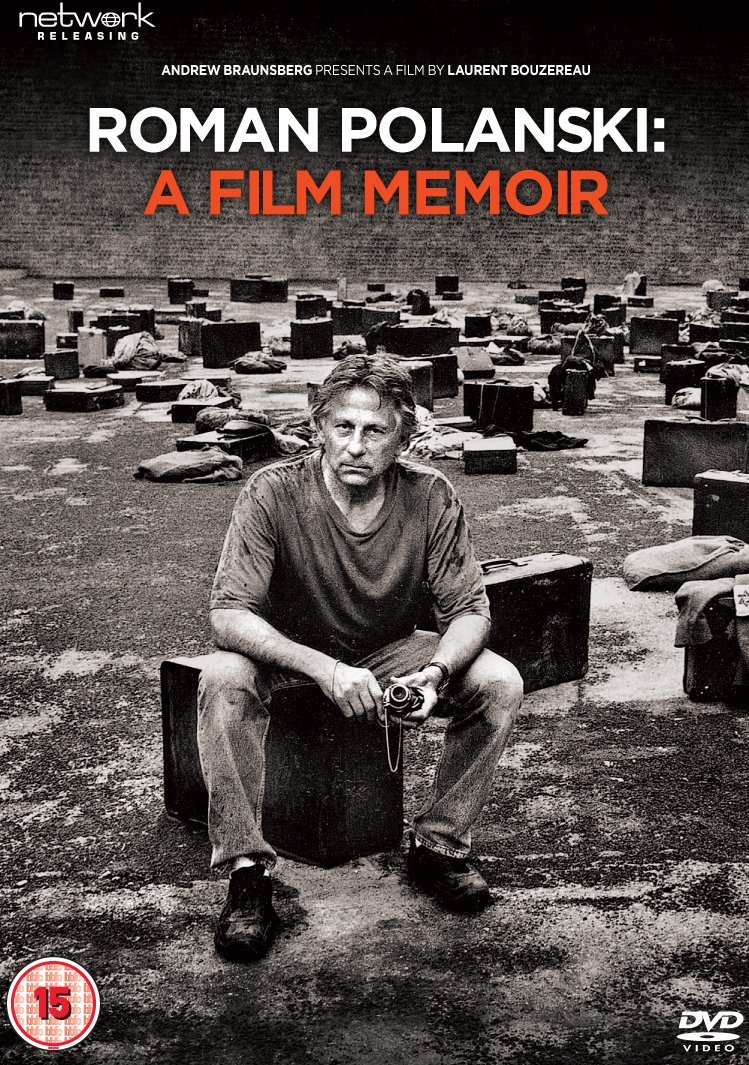

Roman Polanski: A Film Memoir (Laurent Bouzereau, 2011)

Unarguably a great director, Roman Polanski has had a turbulent life and, thanks to the fallout from his arrest for statutory rape in 1977 (after which he fled America), a controversial one. In this documentary, directed by Laurent Bouzereau – who during the LaserDisc era made a name for himself as the director of some superb retrospective documentaries about the production of landmark films such as Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) – Polanski’s friend and colleague Andrew Braunsberg sits down with Polanski and interviews the director about his life. Unarguably a great director, Roman Polanski has had a turbulent life and, thanks to the fallout from his arrest for statutory rape in 1977 (after which he fled America), a controversial one. In this documentary, directed by Laurent Bouzereau – who during the LaserDisc era made a name for himself as the director of some superb retrospective documentaries about the production of landmark films such as Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) – Polanski’s friend and colleague Andrew Braunsberg sits down with Polanski and interviews the director about his life.

The documentary begins with an account of Polanski being detained in Zurich in 2009, on charges relating to the outstanding warrant for his arrest in America. Then the interview tracks back through Polanski’s childhood in Krakow during the Nazi occupation of Poland, where he witnessed the liquidation of the ghettos, during which his mother and sister were taken to Auschwitz and his father was transported to Mauthausen. Braunsberg and Polanski discuss the filmmakers’ reunification with his father after the war and his studies which led to his career as a director. His relationship with Sharon Tate, and her murder by Charles Manson’s ‘family’, is covered in detail before moving on to Polanski’s rape of then-13 year old Samantha Gailey in 1977, his arrest for that crime, the subsequent trial and his flight from the US (first to London, then to Paris).

As the setup might suggest, there’s little objectivity here: Braunsberg is Polanski’s friend and supporter, and we are offered Polanski’s point of view only – which is frustrating, as so much of the film focuses on Polanski’s arrest. Marina Zenovich’s Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired (2008), and its follow-up Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out (2013), are possibly ‘better’ documentaries if you want an impartial account of the statutory rape case that has followed Polanski for the last thirty-five years.

Nevertheless, Polanski is remarkably candid here. The focus on Polanski’s life thankfully sidesteps the oft-repeated reductive assertion that Polanski’s art is simply an outgrowth of his personal experiences (most commonly embodied in the cliché that his adaptation of Macbeth was a response to the murder of Tate), which Polanski notoriously prickled against when interviewed by Mark Cousins for the documentary Scene by Scene with Roman Polanski in 2000. Given the drama in Polanski’s life, it’s tempting to interpret his films in this way – and it has certainly become a cliché in writings about Polanski – but this type of biographical criticism tends to deny the complexities of many of Polanski’s films in favour of a singular focus on the corollaries between Polanski’s work and events in his life. Nevertheless, Polanski is remarkably candid here. The focus on Polanski’s life thankfully sidesteps the oft-repeated reductive assertion that Polanski’s art is simply an outgrowth of his personal experiences (most commonly embodied in the cliché that his adaptation of Macbeth was a response to the murder of Tate), which Polanski notoriously prickled against when interviewed by Mark Cousins for the documentary Scene by Scene with Roman Polanski in 2000. Given the drama in Polanski’s life, it’s tempting to interpret his films in this way – and it has certainly become a cliché in writings about Polanski – but this type of biographical criticism tends to deny the complexities of many of Polanski’s films in favour of a singular focus on the corollaries between Polanski’s work and events in his life.

Here, there is no doubt that the interview focuses on Polanski’s life rather than his cinema: his work as a filmmaker isn’t mentioned directly until over forty minutes into the documentary (almost halfway through its running time). Even then, only passing mention is made of his films – when they led to Polanski meeting significant people in his life (Braunsberg, during the production of Repulsion; Tate, during the filming of The Fearless Vampire Killers), or as markers to denote the passage of time. Polanski briefly mentions his feelings towards his own films, suggesting (interestingly) that Repulsion ‘was a bit of a prostitution’ and that Cul-de-sac was the ‘first film of which I was truly proud’.

Polanski shows a sense of humour about his detainment in 2009: he had arrived in Zurich to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Zurich Film Festival. ‘We hope your stay with us will be both exciting and inspiring’, the letter inviting Polanski to the festival asserted. ‘It certainly was’, Polanski quips. On the other hand, he is reduced to tears when Braunsberg asks him to reflect on the liquidation of the ghetto in which, as a child, he lived, and the moments his mother, sister and father were transported to the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Mauthausen respectively (with Polanski’s father, who had been rounded up with other Jews from the ghetto, shooing him away and telling him to ‘Piss off’). Polanski shows a sense of humour about his detainment in 2009: he had arrived in Zurich to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Zurich Film Festival. ‘We hope your stay with us will be both exciting and inspiring’, the letter inviting Polanski to the festival asserted. ‘It certainly was’, Polanski quips. On the other hand, he is reduced to tears when Braunsberg asks him to reflect on the liquidation of the ghetto in which, as a child, he lived, and the moments his mother, sister and father were transported to the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Mauthausen respectively (with Polanski’s father, who had been rounded up with other Jews from the ghetto, shooing him away and telling him to ‘Piss off’).

Tate’s pregnancy, Polanski says here, reminded him of his own mother, who was pregnant at the time she was taken to Auschwitz. The prospect of the birth of his first child was part of an ‘extremely happy period of my life, which lasted, unfortunately, not very long’, and offered Polanski ‘a normal life’ – something which, by implication, he had been denied by his childhood experiences. However, this was snatched away when Tate was brutally murdered. Polanski talks about the visit he made to the scene of his wife’s murder, as a way of coming to terms with what had happened (and we are shown some of the photographs of him there). Polanski was initially convinced that the murderers must be someone within his social circle: until the arrest of Manson and his followers, it was inconceivable to him that the crime was committed by ‘a bunch of people who came to kill for killing only’.

Polanski is deeply candid when talking about the events in Zurich in 2009: he talks in detail about the moment of his arrest, and when Braunsberg asks him when Polanski realised he was in ‘deep shit’, Polanski notes that such situations are not as simple as that: they are comparable with being diagnosed with a disease, he says, in which you continually hope that someone will find a cure; but as the days wear on, your body begins to succumb to the disease until, one day, you begin to comprehend just how grave the situation really is.

The film runs for 90:16 mins (PAL).

Video

The documentary is shot (on digital video) in a matter-of-fact manner, using a two camera setup, in Polanski’s home in Switzerland. Interspersed throughout the documentary are still photographs, newsreel footage, and clips from Polanski’s films.

The documentary is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1 (although some archive news footage is presented in 1.33:1, and a few film clips are presented in 2.35:1), with anamorphic enhancement.

Audio

The documentary has a two-channel stereo track, which is clean and clear throughout.

Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole extra is a trailer for the documentary (1:18).

Overall

Have no doubt about it: this is a documentary about Polanski and his turbulent life, rather than his films. Polanski’s arrest in 2009 hangs over this documentary portrait, which is a shame as it seems that this event has come to define Polanski in popular media, and in fact has arguably come to overshadow his work – here, it certainly overshadows Braunsberg’s interview with Polanski, framing the filmmaker’s reflections on his experiences in Krakow during the Holocaust and the tragic murder of his pregnant wife. The focus on Polanski’s life, and the lack of balance (the documentary only features Polanski’s perspective on events) may irk some viewers: those critical of Polanski may interpret this documentary as little more than a hagiography. (Marina Zenovich’s documentaries about Polanski offer a more objective examination of the events surrounding the rape case that has dogged his life since the late 1970s.) The film wisely seems to make an effort not to confuse the artist with his art, but this has the concomitant effect of offering little insight into Polanski’s films – so don’t approach this documentary expecting insight into Polanski’s work. More than anything else, it’s a fascinating portrait of a man who has lived through (and, through his assault of Gailey, inflicted) so much trauma.

The presentation of the documentary on this disc is very good, though sadly there’s little contextual material. The documentary is being released concurrently by Network on DVD, via iTunes and in selected cinemas.

|