|

|

Ipcress File (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st August 2014). |

|

The Film

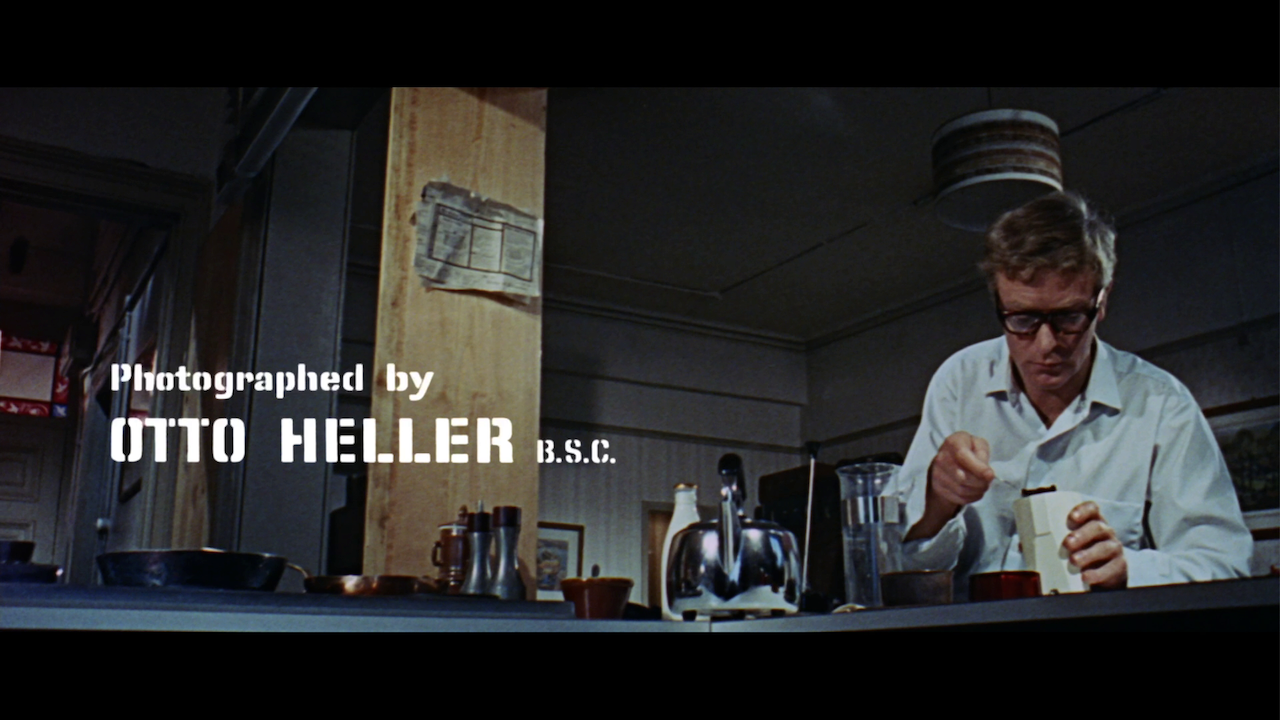

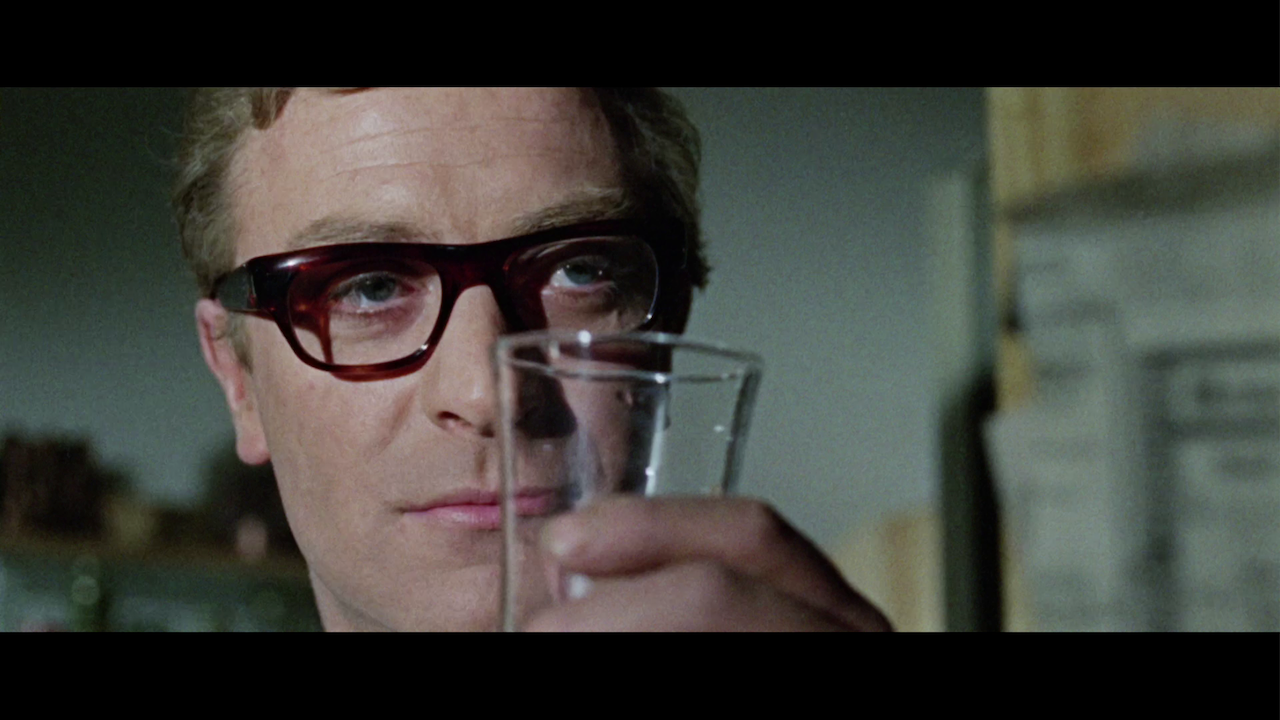

The IPCRESS File (Sidney J Furie, 1965)  Opening with the abduction of a scientist, Radcliffe (Aubrey Richards), aboard a train, during which his guard Taylor (Charles Rea) is killed, The Ipcress File (Sidney J Furie, 1965) soon introduces its protagonist, military intelligence agent Harry Palmer (Michael Caine) as the antithesis of the James Bond of both Ian Fleming’s novels and the various film adaptations (Terence Young’s Thunderball was the gadget-obsessed Bond picture that was released in the same year as The Ipcress File). In contrast with the sensual and glamorous titles sequences of the Bond films (for example, the shimmering words appearing over the equally shimmering body of the dancer in Robert Brownjohn’s titles sequence for From Russia With Love, 1962), the titles sequence for The Ipcress File, which emphasises the banality of Palmer’s existence, wouldn’t look out of place in a kitchen sink drama. Palmer is introduced being woken by his alarm clock. A point of view shot from Palmer’s perspective follows: a profoundly blurred image of Palmer’s bedroom. Palmer puts on his horn-rimmed spectacles and everything comes into focus. As the film’s titles play out, accompanied by John Barry’s cimbalon-based score, we see Palmer making his breakfast and drinking coffee before leaving for work. His task is a mundane surveillance duty. He is soon pulled off this and ordered to see his commanding officer, Colonel Ross (Guy Doleman). Opening with the abduction of a scientist, Radcliffe (Aubrey Richards), aboard a train, during which his guard Taylor (Charles Rea) is killed, The Ipcress File (Sidney J Furie, 1965) soon introduces its protagonist, military intelligence agent Harry Palmer (Michael Caine) as the antithesis of the James Bond of both Ian Fleming’s novels and the various film adaptations (Terence Young’s Thunderball was the gadget-obsessed Bond picture that was released in the same year as The Ipcress File). In contrast with the sensual and glamorous titles sequences of the Bond films (for example, the shimmering words appearing over the equally shimmering body of the dancer in Robert Brownjohn’s titles sequence for From Russia With Love, 1962), the titles sequence for The Ipcress File, which emphasises the banality of Palmer’s existence, wouldn’t look out of place in a kitchen sink drama. Palmer is introduced being woken by his alarm clock. A point of view shot from Palmer’s perspective follows: a profoundly blurred image of Palmer’s bedroom. Palmer puts on his horn-rimmed spectacles and everything comes into focus. As the film’s titles play out, accompanied by John Barry’s cimbalon-based score, we see Palmer making his breakfast and drinking coffee before leaving for work. His task is a mundane surveillance duty. He is soon pulled off this and ordered to see his commanding officer, Colonel Ross (Guy Doleman).

Ross tells Palmer that he is to be transferred to another unit, headed by Major Dalby (Nigel Green). (In the novel, this is identified as a civilian intelligence unit, WOOC(P).) Dalby’s unit is investigating a ‘brain drain’: scientists such as Radcliffe have been going missing at a rate of 126 over the past two years. Eric Ashby Grantby (Frank Gatliff) is suspected of having abducted Radcliffe with the hope of selling the scientist to the enemy. Dalby commands his unit, including Palmer, Courtney (Sue Lloyd) and Jock (Gordon Jackson), to make contact with Grantby and retrieve Radcliffe. Using a connection within Scotland Yard, Palmer makes contact with Grantby in the Science Museum Library in the Royal College of Science. Palmer stages a raid on an old warehouse but comes up empty – except for a strip of magnetic tape which is marked ‘IPCRESS’.  Palmer is approached by Ross, who asks Palmer to pass on to him information about Dalby’s investigation. Palmer refuses. An exchange is arranged: Grantby will return Radcliffe in exchange for twenty-five thousand pounds. The exchange doesn’t go completely to plan: Radcliffe is returned, but seeing a figure skulking in the corner of the underground garage where the meeting has taken place, Palmer opens fire, killing a CIA agent. Radcliffe is alive and well, but he seems to be suffering from a form of amnesia, which renders him useless as a scientist. Palmer is approached by Ross, who asks Palmer to pass on to him information about Dalby’s investigation. Palmer refuses. An exchange is arranged: Grantby will return Radcliffe in exchange for twenty-five thousand pounds. The exchange doesn’t go completely to plan: Radcliffe is returned, but seeing a figure skulking in the corner of the underground garage where the meeting has taken place, Palmer opens fire, killing a CIA agent. Radcliffe is alive and well, but he seems to be suffering from a form of amnesia, which renders him useless as a scientist.

Jock shows Palmer a book he has discovered, ‘Induction of Psychoneuroses by Conditioned Reflex Under Stress’, which Jock suggests is what IPCRESS stands for. However, Jock is soon murdered whilst driving Palmer’s car. Shortly after, Palmer finds another CIA agent, who has been tailing Palmer, dead in Palmer’s home. Realising that he has been framed for the death of the American agent and fearing for his life, Palmer disappears underground and takes a train to Paris. However, he is abducted by Grantby’s men. Told that he is in Albania, Palmer is held in a cell, tortured and exposed to the IPCRESS conditioning process: once a day, he is placed in a metal, windowless cell, the IPCRESS audio tape playing white noise and a cacophony of lights projected onto the metal walls of the container in which he is held. During this process, Grantby conditions Palmer to respond to a trigger phrase. However, Palmer manages to escape, soon realising that he is not in fact in Albania: he has been held in a warehouse in London. He contacts Dalby and Ross, and realises that one of these two men is a traitor who is in league with Grantby. Not only must Palmer fight to make sure that the traitor is exposed, but he must also combat the conditioning to which he has been subjected.  The story goes that after the premiere of Zulu (Cy Endfield, 1964), Caine visited the London Pickwick Club with his friend Terence Stamp, where Caine met Harry Saltzman. Impressed with Caine’s work in Zulu, Saltzman offered Caine the role of Harry Palmer, who Saltzman envisioned as ‘a thinking man’s spy, a character who doesn’t always get the girls, a secret agent nervous around guns. A spy who doesn’t want to be a spy at all’ (Britton, 2006: 126). In Typical Men: The Representation of Masculinity in Popular British Cinema (2003), Andrew Spicer labels Harry Palmer as ‘Bond’s only important rival as an action hero’ (76). Producer Harry Saltzman referred to Palmer as an ‘anti-hero, someone people would identify with just as they fantasised with Bond’ (quoted in ibid.). Caine himself would later describe Palmer as ‘a winner who comes on like a loser’ (quoted in Chibnall, 2003: 27). The story goes that after the premiere of Zulu (Cy Endfield, 1964), Caine visited the London Pickwick Club with his friend Terence Stamp, where Caine met Harry Saltzman. Impressed with Caine’s work in Zulu, Saltzman offered Caine the role of Harry Palmer, who Saltzman envisioned as ‘a thinking man’s spy, a character who doesn’t always get the girls, a secret agent nervous around guns. A spy who doesn’t want to be a spy at all’ (Britton, 2006: 126). In Typical Men: The Representation of Masculinity in Popular British Cinema (2003), Andrew Spicer labels Harry Palmer as ‘Bond’s only important rival as an action hero’ (76). Producer Harry Saltzman referred to Palmer as an ‘anti-hero, someone people would identify with just as they fantasised with Bond’ (quoted in ibid.). Caine himself would later describe Palmer as ‘a winner who comes on like a loser’ (quoted in Chibnall, 2003: 27).

Len Deighton’s 1962 source novel (The IPCRESS File – note the difference in presentation) had been conceived as a ‘reaction against the glossy, unrealistic depiction of espionage in the novels of Ian Fleming (a certain Puritanism was a factor at the time, something that is less apropos these days now that Fleming’s considerable virtues have been recognised’ (Forshaw, 2012: np). Deighton’s novel drew focus on the banality of the work of an intelligence agent, marrying this with a first-person narration that was reminiscent of the kind associated with American hardboiled fiction (for example, Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe novels, or Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer books). The anonymous protagonist of Deighton’s novel was given the name ‘Harry Palmer’ after Saltzman and Caine collaborated in an attempt to find a suitable moniker for their spy who was ‘an ordinary man able to disappear in crowds’ (Britton, op cit.: 126). The decision to make Palmer a keen cook was inspired by Len Deighton’s alternate career as a cookery writer for The Observer. In fact, Deighton’s hands stood in for Caine’s during one sequence in the film, in which, whilst preparing a meal, Palmer is required to crack two eggs in one hand – something Caine was unable to do. Palmer’s interest in cooking reputedly offered a challenge to the Hollywood producers’ concept of masculinity and how men should be represented in films: in his autobiography The Elephant to Hollywood (2010), Caine notes that The Ipcress File ‘still ran into the old movie executive problem […] After the first rushes we got a cable from Hollywood. “Dump Caine’s spectacles and make the girl cook the meal – he is coming across as a homosexual”’ (np; emphasis in original).  The contrast with the Bond films is not only in the characterisation of Palmer, but also in the environments in which Palmer finds himself. Ken Adam worked as the film’s production designer, and in stark comparison with Adam’s work on the Bond films, the world of The Ipcress File comprises dank, overcast London streets and dreary nondescript offices decorated in drab greens and browns. The home of Dalby’s unit is disguised as the offices of ‘Astra Fireworks’. The team share cramped desks in a dreary office, where they must complete endless reams of paperwork. Jock tells Palmer that a field report must be completed after every lead into the whereabouts of Grantby has been investigated. ‘You mean, I’ve got to ask about Grantby in nineteen different places, and make up nineteen lots of silly answers?’, Palmer grumbles. However, despite their antiquated methods, Palmer and his colleagues are faced with a new threat, represented by the IPCRESS technique. Whilst Palmer is subjected to the IPCRESS method, one of the scientists working for Grantby notes that, ‘The Gestapo and MVD used to bear a man for months to get him to this state’. Grantby observes that those methods are ‘old fashioned and crude’, and they also work much more slowly than the IPCRESS method. The contrast with the Bond films is not only in the characterisation of Palmer, but also in the environments in which Palmer finds himself. Ken Adam worked as the film’s production designer, and in stark comparison with Adam’s work on the Bond films, the world of The Ipcress File comprises dank, overcast London streets and dreary nondescript offices decorated in drab greens and browns. The home of Dalby’s unit is disguised as the offices of ‘Astra Fireworks’. The team share cramped desks in a dreary office, where they must complete endless reams of paperwork. Jock tells Palmer that a field report must be completed after every lead into the whereabouts of Grantby has been investigated. ‘You mean, I’ve got to ask about Grantby in nineteen different places, and make up nineteen lots of silly answers?’, Palmer grumbles. However, despite their antiquated methods, Palmer and his colleagues are faced with a new threat, represented by the IPCRESS technique. Whilst Palmer is subjected to the IPCRESS method, one of the scientists working for Grantby notes that, ‘The Gestapo and MVD used to bear a man for months to get him to this state’. Grantby observes that those methods are ‘old fashioned and crude’, and they also work much more slowly than the IPCRESS method.

The role of Palmer came immediately after Caine’s atypical performance as the upper class gentleman officer Lieutenant Bromhead in Zulu, who during the film comes into conflict with Stanley Baker’s more proletarian Lieutenant Chard. In contrast with Bromhead, Harry Palmer is resolutely working class; this is the type of character that Caine would become associated with throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Caine’s shabby appearance and his horn-rimmed spectacles exaggerated his ordinariness. However, like Bond Palmer is ‘concern[ed] with lifestyle’ (Spicer, op cit.: 77). Despite his working class origins, Palmer, through his fascination with Mozart and his interest in fine cuisine, is depicted as ‘more sophisticated, discriminating and knowledgeable than his upper-class superiors’ (ibid.: 77-8). During one sequence, Dalby and Palmer meet with Grantby at a performance of the Band of the Irish Guards. Palmer and Dalby sit together, Dalby swinging his umbrella (badly) in time with the music. ‘What’s this called?’, Palmer asks. ‘The Thin Red Line’, Dalby informs him: ‘Good, patriotic stuff. Got a proper rhythm to it’. Palmer looks unimpressed. ‘Not quite your line, eh’, Dalby observes. ‘I prefer Bach or Mozart’, Palmer says. ‘You’re lucky. Mozart next’, Dalby tells him. ‘Oh, really’, Palmer says, clearly not pleased at the idea of a military brass band playing Mozart. As the band breaks into ‘The Marriage of Figaro’, Grantby, who has seated himself next to Dalby, notes that ‘There’s a delicacy and precision to Mozart’s work. Transcribes remarkably well from the orchestra to the military band, don’t you agree’. ‘Oh yes, of course’, Dalby notes, rolling his eyes in the direction of Palmer.  Shortly before this sequence, Palmer meets with Ross in an American-style supermarket. Ross looks at Palmer’s purchases, as chirpy muzak plays in the background. ‘Champignon. You’re paying ten pence more for a fancy French label’, Ross tells Palmer, ‘If you want button mushrooms, you’d get better value on the next shelf’. ‘It’s not just the label. These do have a better flavour’, Palmer informs his superior. ‘Of course, you’re quite a gourmet, aren’t you, Palmer’, Ross comments dryly. ‘I haven’t seen you here before, sir’, Palmer observes. ‘Yes, well I don’t really care for these American shopping methods. One has to move with the times, I suppose, hmm’, Ross says. ‘Yes, that’s very nice’, Palmer responds. ‘Is it really?’, Ross asks. In the supermarket sequence, Ross is the character with authority, but he is shown to be out of place within this environment: Ross is ‘a product of the old British class system, university educated, an officer and middle class. Yet here, in this emergent Britain, he [Ross] is the one who is socially adrift; confused and outsmarted in every department by his one-time inferior’ (Morgan-Tamosunas, 2004: 70). Shortly before this sequence, Palmer meets with Ross in an American-style supermarket. Ross looks at Palmer’s purchases, as chirpy muzak plays in the background. ‘Champignon. You’re paying ten pence more for a fancy French label’, Ross tells Palmer, ‘If you want button mushrooms, you’d get better value on the next shelf’. ‘It’s not just the label. These do have a better flavour’, Palmer informs his superior. ‘Of course, you’re quite a gourmet, aren’t you, Palmer’, Ross comments dryly. ‘I haven’t seen you here before, sir’, Palmer observes. ‘Yes, well I don’t really care for these American shopping methods. One has to move with the times, I suppose, hmm’, Ross says. ‘Yes, that’s very nice’, Palmer responds. ‘Is it really?’, Ross asks. In the supermarket sequence, Ross is the character with authority, but he is shown to be out of place within this environment: Ross is ‘a product of the old British class system, university educated, an officer and middle class. Yet here, in this emergent Britain, he [Ross] is the one who is socially adrift; confused and outsmarted in every department by his one-time inferior’ (Morgan-Tamosunas, 2004: 70).

Palmer is also rebellious. His anti-authoritarian streak exhibits itself through his biting sarcasm. When Ross tells Palmer that he is to be transferred to Dalby’s unit, Ross notes dryly, ‘You just love the army, don’t you’. ‘Oh, yes’, Palmer replies sarcastically, ‘I just love the army, sir’. Ross informs Palmer that Dalby ‘doesn’t even have my sense of humour’, and Palmer responds, again sarcastically, ‘Yes, I shall miss that, sir’. In Deighton’s novels, the character is openly resentful of the establishment and its focus on having the ‘right’ background and attending the ‘right’ school. Spicer notes that this film adaptation ‘pinpoints these attitudes in the tradition of the “bolshie” Cockney working-class Other Ranker’, a character type familiar from war films (Spicer, op cit.: 77). Palmer, Spicer argues, ‘is imbued with traditional working-class certainties: bosses are vile, work awful and the only response is to look after Number One’ (ibid.). Palmer has been drafted into intelligence work by Ross, who took him out of a military prison where he was being held for his involvement in black market activities in Berlin. Palmer is offered the choice of working for Ross or returning to prison, and at one point Ross tries to blackmail Palmer into microfilming the all-important IPCRESS file by telling Palmer that he will be sent back to jail if he fails to do so.  Palmer’s insolence is signaled from the outset. In the post-titles sequence, when he arrives at the location (a derelict building) in which he has been ordered to carry out his surveillance task, he relieves a colleague who reminds Palmer that he is twenty minutes late. ‘You ought to remember you’re still in the army, boyo’, his colleague says. ‘Tell you what’, Palmer responds dryly, ‘you remember for me’. Shortly after, Palmer is shown demonstrating his contempt for the paperwork he must complete on the surveillance duty that he has been assigned. We are shown Palmer writing, and narrating, ‘They had an extra pint of milk today, which either means that there are more people over there, or they’re drinking more tea’. Finding this little joke highly amusing, Palmer sniggers. In his review of the film, Alexander Walker noted that Palmer ‘cultivates those tiny acts of insolence – like leaving doors open behind him – that annoy his chiefs’ (quoted in Morgan-Tamosunas, op cit.: 71). Owing to this, Palmer’s record, passed on from Ross to Dalby, declares that Palmer is ‘Insubordinate; insolent; a trickster, perhaps with criminal tendencies’. However, as Ross reassures Dalby, ‘He’s [Palmer is] a little subordinate, but a good man’. Palmer’s insolence is signaled from the outset. In the post-titles sequence, when he arrives at the location (a derelict building) in which he has been ordered to carry out his surveillance task, he relieves a colleague who reminds Palmer that he is twenty minutes late. ‘You ought to remember you’re still in the army, boyo’, his colleague says. ‘Tell you what’, Palmer responds dryly, ‘you remember for me’. Shortly after, Palmer is shown demonstrating his contempt for the paperwork he must complete on the surveillance duty that he has been assigned. We are shown Palmer writing, and narrating, ‘They had an extra pint of milk today, which either means that there are more people over there, or they’re drinking more tea’. Finding this little joke highly amusing, Palmer sniggers. In his review of the film, Alexander Walker noted that Palmer ‘cultivates those tiny acts of insolence – like leaving doors open behind him – that annoy his chiefs’ (quoted in Morgan-Tamosunas, op cit.: 71). Owing to this, Palmer’s record, passed on from Ross to Dalby, declares that Palmer is ‘Insubordinate; insolent; a trickster, perhaps with criminal tendencies’. However, as Ross reassures Dalby, ‘He’s [Palmer is] a little subordinate, but a good man’.

During the exchange between Dalby’s unit and Grantby’s men, during which Radcliffe is returned, Palmer shoots at a figure in the shadows of the underground parking garage. It’s a CIA agent. ‘Congratulations, Palmer. You’ve just killed an American agent’, Dalby observes, before later noting to Ross, ‘That’ll teach them not to poach on our preserve’. The man Palmer shoots was also at the first meeting between Palmer and Grantby, in the library of the Science Museum. The killing of the CIA agent, accidental though it may be, threatens to undermine the audience’s sympathy for Palmer. Morgano-Tomosunas notes that Palmer ‘is far from the infallible, jet-setting figure audiences were beginning to associate with British spy films of the period’ (op cit.: 71). Where the Bond films may be considered ‘a projection of classless, consumerist fantasies’, by contrast Palmer was ‘definitely “one of us”; a working spy, doing his rather unpleasant job for Queen and country, but using his naïve, working-class guile to get the best out of that deal that he can’ (ibid.). Palmer’s first thought when he is told that he will be transferred to Dalby’s unit, is to ask Ross, ‘Is this a promotion, sir?’ ‘Sort of’, Ross replies. ‘Any more money?’, Palmer asks. He is told that his salary may be upped from £1300 to £1400, plus expenses. ‘Oh, thank you, sir’, Palmer responds, ‘Now I can get that new infrared grill’. Commenting on the Palmer ‘type’ in British film, Penelope Gilliatt noted that ‘[i]ntransigence and opportunism are as central now to sex-appeal in English male acting as charm and height used to be. Make a crack, cheat the boss, expect nothing, go for the lot, and never commit a murder except on expenses. The girls fall like skittles’ (quoted in Spicer, op cit.: 78).

Video

The Ipcress File was shot in Techniscope, the economical 2-perf widescreen format introduced in Italy in 1963. Techniscope achieved a widescreen ratio of approximately 2.35:1 without the use of anamorphic lenses. This decreased production costs (halving the amount of film stock used and reducing the need to hire expensive anamorphic lenses), though it is said that the lab costs of films shot in Techniscope were higher than those of films shot using more conventional anamorphic widescreen processes – one of the reasons why Techniscope became increasingly less popular during the late-1970s. The Ipcress File was shot in Techniscope, the economical 2-perf widescreen format introduced in Italy in 1963. Techniscope achieved a widescreen ratio of approximately 2.35:1 without the use of anamorphic lenses. This decreased production costs (halving the amount of film stock used and reducing the need to hire expensive anamorphic lenses), though it is said that the lab costs of films shot in Techniscope were higher than those of films shot using more conventional anamorphic widescreen processes – one of the reasons why Techniscope became increasingly less popular during the late-1970s.

Release prints were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. However, during the 1960s, when Techniscope films were blown-up using dye transfer processes in use by Technicolor Italia, it was possible to skip the dupe negative step and ‘save’ a generation, thus resulting in an image with a finer grain structure and deeper blacks (characteristics of films produced using dye transfer processes generally, not just those shot in Techniscope). In the 1970s, for economic reasons dye transfer printing for films shot in Techniscope was replaced with the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative (and an additional ‘generation’ for the material). This resulted in a more coarse grain structure to Techniscope films released in the 1970s and beyond. Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to use lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)  This presentation of The Ipcress File is very pleasing. I’m unsure whether it is taken from a 4-perf blow-up or the original 2-perf negative, but either way the film as presented here has quite a coarse (but entirely organic) grain structure, more comparable to that of Techniscope films shot in the late-1970s (printed using Kodak’s usual colour printing process) than contemporaneous films shot in Techniscope (and printed using the dye transfer process) such as A Fistful of Dollars – so perhaps The Ipcress File was printed using the more prevalent Kodak colour printing process. Alternatively, much of the film is shot in fairly low-light scenarios, so the film stock may have been ‘pushed’ slightly, resulting in a more coarse grain structure. Certainly, the characteristics of Techniscope films are on display here, exploited by cinematographer Otto Heller: there’s an abundance of short focal lengths, accompanied by a great depth of field (even in low-light sequences). Interiors (the offices of Dalby’s unit and the library at the Science Museum) are shown in deep focus, despite being shot in low light. The camera is often placed behind objects such as telephones, at a canted angle, with the object in the foreground and the action in the background both presented in focus: the obtuse angles and shots framed through objects ‘conveyed the clandestine, eavesdropping nature of the spy business’ (Britton, 2005: 132). This presentation of The Ipcress File is very pleasing. I’m unsure whether it is taken from a 4-perf blow-up or the original 2-perf negative, but either way the film as presented here has quite a coarse (but entirely organic) grain structure, more comparable to that of Techniscope films shot in the late-1970s (printed using Kodak’s usual colour printing process) than contemporaneous films shot in Techniscope (and printed using the dye transfer process) such as A Fistful of Dollars – so perhaps The Ipcress File was printed using the more prevalent Kodak colour printing process. Alternatively, much of the film is shot in fairly low-light scenarios, so the film stock may have been ‘pushed’ slightly, resulting in a more coarse grain structure. Certainly, the characteristics of Techniscope films are on display here, exploited by cinematographer Otto Heller: there’s an abundance of short focal lengths, accompanied by a great depth of field (even in low-light sequences). Interiors (the offices of Dalby’s unit and the library at the Science Museum) are shown in deep focus, despite being shot in low light. The camera is often placed behind objects such as telephones, at a canted angle, with the object in the foreground and the action in the background both presented in focus: the obtuse angles and shots framed through objects ‘conveyed the clandestine, eavesdropping nature of the spy business’ (Britton, 2005: 132).

Network’s 2006 special edition DVD suffered from cropping on all four sides of the frame and some noticeable contrast boosting. Thankfully, none of that is present here. The presentation on this new Blu-ray from Network isn’t remarkably different from that of ITV’s Blu-ray release of this film, which was issued in 2008: the compositions are the same, and the contrast levels are similar, if not identical. However, the encode on Network’s new Blu-ray release is noticeably stronger (the ITV Blu-ray used MPEG-2 compression, whereas Network’s new Blu-ray uses the more advanced AVC compression). In sum, this is a very pleasing presentation of the film, better than any of the film’s previous home video releases. A direct visual comparison of the Network and ITV Blu-rays is below. The images from the Network disc are above; the images from the ITV disc are below.

Audio

There are two audio options: a LPCM two-channel mono track and a newer DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix. The mono track is rich and dynamic, showcasing Barry’s score superbly and evidencing a strong dynamic range. It’s head and shoulders above the lossy Dolby Digital track on the ITV Blu-ray. The newer 5.1 mix is less impressive. There’s good dynamic range, but the track sounds artificial, and the dialogue often seems mixed low. Optional English subtitles are provided.

Extras

The release contains an excellent range of contextual material, much of it ported over from Network’s 2006 SE DVD release. Commentary with director Sidney J Furie and editor Peter Hunt. This is the same commentary that first appeared on the Roan Group LaserDisc release of the film in 1998, and has appeared on the Anchor Bay DVD released in 1999 and the Network SE DVD release that appeared in 2006. It’s an excellent track, filled with information. Video extras include: Interview with Sir Michael Caine (19:15, SD). Caine discusses how he became involved in the making of the film and his experiences during production. Interview with Production Designer Sir Ken Adam (10:30, SD) 'The IPCRESS File: Michael Caine Goes Stella' comedy sketch (5:01, SD). Phil Cornwell revives his impersonation of Caine, familiar from the BBC’s funny little series Stella Street (1997-2000) and Peter Richardson’s less amusing 2004 film of the same title. 'Candid Caine' 1969 documentary (44:19, SD). This thorough account of Caine’s career, till the production of this documentary in 1969, is a superb inclusion. Original theatrical trailer (1:04, SD) Original US radio commercials (2:44, SD) Galleries: - Production image gallery (2:24) - Behind the scenes image gallery (2:57) - Portrait image gallery (1:17) - Promotional image gallery (2:56) Textless material (4:13, SD). This is the opening titles sequence, sans the titles and music.

Overall

The Ipcress File is a superb film that still feels fresh. Caine’s performance as Palmer has become iconic; Palmer’s approach to authority and the bind in which he finds himself still feel very contemporary. The presentation of the film on this disc is very good, eclipsing previous releases – especially in terms of the lossless audio options available here (the mono track is stronger than the newer 5.1 mix, however). The excellent range of contextual material fleshes out this new Blu-ray release. This is an extremely pleasing release and it comes with a very strong recommendation. The Ipcress File is a superb film that still feels fresh. Caine’s performance as Palmer has become iconic; Palmer’s approach to authority and the bind in which he finds himself still feel very contemporary. The presentation of the film on this disc is very good, eclipsing previous releases – especially in terms of the lossless audio options available here (the mono track is stronger than the newer 5.1 mix, however). The excellent range of contextual material fleshes out this new Blu-ray release. This is an extremely pleasing release and it comes with a very strong recommendation.

References Britton, Wesley Alan, 2006: Onscreen and Undercover: The Ultimate Book of Movie Espionage. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers Britton, Wesley Alan, 2005: Beyond Bond: Spies in Fiction and Film. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers Caine, Michael, 2010: The Elephant to Hollywood. London: Hodder & Stoughton Chibnall, Steve, 2003: British Film Guides: Get Carter. London: I B Tauris Forshaw, Barry, 2012: British Crime Film: Subverting the Social Order. London: Palgrave-Macmillan Morgan-Tamosunas, Rikki, 2004: ‘Deconstructing Paco Rabal: Masculinity, Myth and Meaning’. In: Powrie, Phil et al (eds), 2004: The Trouble with Men: Masculinities in European and Hollywood Cinema. London: Wallflower Press: 54-76 Spicer, Andrew, 2003: Typical Men: The Representation of Masculinity in Popular British Cinema. London: I. B. Tauris This review has been kindly sponsored by:  >

|

|||||

|