|

|

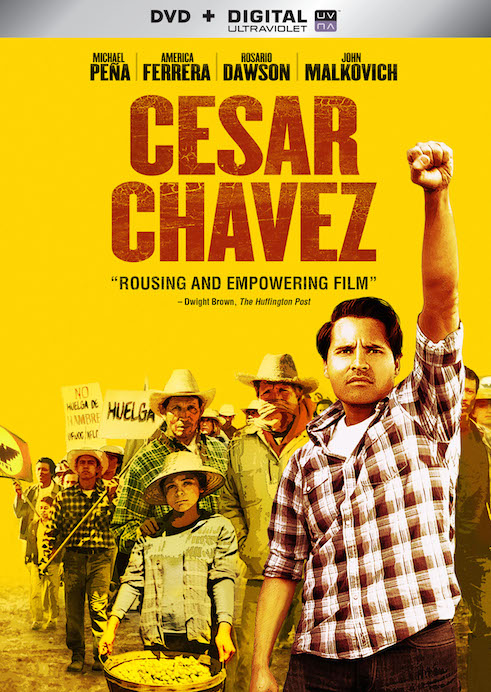

Cesar Chavez

R1 - America - Lions Gate Home Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Ethan Stevenson (2nd August 2014). |

|

The Film

“It depends on the man. Everything depends on the man.” The rallying cry of the United Farm Workers Association, “Sí, se puede,” has a number of meanings that are all basically the same. The slogan was thought up by union co-founders Dolores Huerta and César Chávez, during a hunger strike by the latter, the defacto leader of the UFW, in the 1970's, as a general call for perseverance through adversity. In the specific case, a conflict over collective bargaining between the farm workers and the California millionaires in charge of the agriculture industry at the time. Over the years, “Sí, se puede” has become a phrase popularized within the Chicano, or Latino Civil Rights movement, as a call for community pride. In the original Spanish, “Sí, se puede” conjugates literally as “Yes, it is possible,” although colloquially the more apt, “Yes, it can be done” is generally accepted, as it makes more sense, especially in the intended context of its initial conception. The rough English translation—by far the most widely accepted interpretation of the saying in recent times—is “Yes, one can” or, on an even finer turn of phrase, “Yes, you can.” During President Barack Obama’s initial campaign for office in 2008, his PR team reconfigured the idiom in English as “Yes, we can”, which in a sense is the most universally applicable translation for more than one reason, not first of which is its repatriation outside of the original community. I imagine many involved in bringing César Chávez’ life story to screen, which was no doubt a daunting task—and one, partially, finally realized in Diego Luna’s bluntly-titled biopic, “Cesar Chavez”, which has been wholly homogenized, replete without the accent marks—took to saying “Sí, se puede”, in any one of its many similar meanings, at some point during production. At least I hope so. But forget "can" or, confirming if something is "possible" anymore. It’s been done. Although, I do wonder if those closest to the man and his story ever bothered to ask themselves whether they should do something just because they could? If, in their haste to present a positive depiction of César Chávez, a figure who did more good than he ever did bad, but was far from perfect, that in cleaning off even minor blemishes or actually any context outside of the major reason he’s famous, they forgot someone’s legacy is more than the parts we like to talk about after they're dead. It's the part we don't like to talk about, but perhaps should, that could make biographies far more colorful; less prone to predictability. Contradictions are sometimes far more fascinating than the conventional, but sadly, convention is mostly what's in store when biopics are born. A sanitized, even blandly whitewashed picture with a curiously stunted and unsubtle focus, “Cesar Chavez” makes minimum impact with maximum affection—to the point of twisting a true story into almost pure fiction at times. Honing in on a span of ten years, from 1965 to 1975, when Chávez (played with perfect humility by Michael Peña) organized several strikes, peaceful protests, and marches to raise the awareness of the manipulation of the migrant farmer workers in California. His actions brought about change in an industry overrun by corruption and gave aid to an oppressed workforce. Before Chávez and the UFW began their work, pickers were paid below minimum wage to work long, hard hours of manual labor, and woefully misrepresented. Most workers existed in a legal grey area not especially well regulated in the 1960's—many were not citizens, but rather the second-wave “Braceros”; each one entered into the country through proper means and had papers to live and work in the United States, but few rights beyond that. And so the morally corrupt land owners and employers were free to mistreat how they saw fit. Some even made their pickers pay for drinking water, on hot days and not, out of their meagre earnings. Ultimately, with class-acton litigation from lawyer Jerry Cohen (played by Wes Bentley), eventual legislation, and several other pieces of a much larger and complex puzzle, this all changed. The change came out in large part as a result of a series of non-violent acts, which often found Chávez himself emaciated to the point of near starvation from hunger strikes. His strife soon gained media attention, and with it, he and the others of the UFW, and their supporters in Washington, changed an entire industry, and gave a voice to a disenfranchised minority. Even just in terms of its central figures historical importance, a film about César Chávez most definitely should have been made; now one has been. It’s just such a shame that it’s so dramatically inert and bland; that it isn’t better, although it’s hardly bad. I’m sure the producers involved in bringing “Cesar Chavez” from page to screen had entirely honorable intentions when they first set about telling this tale of labor disputes and a fabled figure in the latino community—especially the immigrant farmers of Salinas and the surrounding areas in California’s Central Valley. But whatever its origins, the film is close enough to pure fiction at times as is dangerous, without being entirely disingenuous, for something ostensibly pretending to be near-documentary. The problem with “Chavez” is two-fold. The smaller issue, only tangentially off-putting and emblematic of an entire genre of filmmaking, is that Diego Luna—best known as an actor in the United States and making his English-language directorial debut with this film, after years of working as a director in his native Mexico, where he has a few television credits and even a previous feature-film to his name—and screenwriters Keir Pearson and Timothy J. Sexton follow the basic biopic formula to a fault. Thankfully, not the full-scale birth-to-death formula, but a smaller one set around the biographic figure’s most significant moments. There’s little, if any, innovation in the screenplay, nor ultimately as put on screen by the director; no attempt to articulate Chávez’ life beyond a series of big moments—including the Delano grape strike, the Salad Bowl strike, and the Modesto march, which all directly or indirectly led to the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act that granted migrant farmers basic rights. The end result of these good intentions get mixed up in modern pop-politics, and amount to a modest and often muddled overview of Chávez’ life and his work as a civil rights leader, which gets the minutiae of the period and the place right—with excellent production design and a lived-in, grittiness courtesy of the effective documentary-like camerawork by Enrique Chediak—and yet so many of the big things not quite, if rarely wrong. The screenplay offers little insight into the complexly of the man, and the film is overly simplified into near nothingness then. Chávez’ collective cohort, Huerta (played by Rosario Dawson), is relegated to a few scenes without any context as to who she really is, because it’s far easier to not explain anything than it is to even pretend men and women can work together as equals, without romantic involvement. At the same time, in terms of regular romance, the film pushes Chávez’ wife, Helen (America Ferrera), to the sidelines as well, making her little more than a homemaker who gave Chávez permission to do what needed to be done, despite her involvement beyond the occasional encouragement. And Chávez’ children are seemingly only kept around for a perfunctory parallel between leadership and fatherhood that’s poorly handled, like a similar born-from-immigrant parallel between Chávez and main antagonist Bogdanovich Senior, played with giddy malevolent glee by the great John Malkovich, and little else. “Chavez” uses cliches as a sort of lazy-man shorthand. Malkovich's character is an amalgamation of several land owners of the day, no one specific real person, vilified to an almost mustache-twirling degree of evil. The backwoods sheriff (Michael Cudlitz) is cast as a simple-minded racist and exists in the story for no other reason than that. Even if essentially the truth, these elements, when stripped of the complexities of reality, remind it's a melodramatic movie, serve barely a purpose beyond plot progression. I suppose exploring either character would take time that the film would otherwise devote to, as it turns out, really not much. Not even Chávez. Cohen’s court case is brushed aside as quickly as it’s introduced; the aid of senator Robert Kennedy (Jack Holmes) is forgotten soon after that; even Chavez’ own literacy initiatives take a back seat to grand moments of speeches and marches and conflict and clashes, where he's amidst a sea of people. These milestone moments in a movement are vignettes mounted on a small scale, but lacking the intimacy and subtlety that would make “Chavez” a far more intestine film. As it stands, the odd middle ground of an epic on a medium budget stretches scope just enough to make it seem that Chávez is lost at times in his own film. The by the numbers plotting, painfully blunt speech-ifying, and generally unsubtle way Luna depicts clashes between the peacefully-protesting workers and the violent, well, racists all but push Chávez, often calling for reason in these moments of conflict, to the canonized level of sainthood. No doubt, he was a good man, but the entire enterprise seems completely unbecoming of a great legacy, yet not for the reasons one might think: in striving for simplicity, reality seems a fiction. Ironically, as familiar as the frame in which Luna and the screenwriters place their story is to the average moviegoer, Chávez himself most likely isn’t. As a native Californian, Chávez’ story was not unknown to me—it’s in our school books, albeit in a sanitized form. But in most other States, especially those without large migrant farming populations, I know his story is considerably less known; a footnote, if even that. And outside of the States, who knows? That’s a much bigger issue for “Cesar Chavez” than any one involved in the production—from Luna, to Peña or the writers, multitude of producers, and even Chávez’ own family, who approved the film and served as consultants—seemed to realize. Events are presented without proper background, as though the information is as well-known Americana as the Star Spangled Banner, which just isn’t the case. And the assumption of knowledge is a huge reason the film stumbles where it should, and could, soar. By ignoring many of the complexities that make men, even someone as goodly as Chávez—who served in the military during WWII but became a pacifist, albeit the incredibly rare one who supported the Vietnam War; who fought for migrant farm workers, but was adamantly opposed to illegal immigration as he believed it weakened the unions, and even gave interviews during the time this film takes place referring to border-crossing undocumented workers using derogatory language—entirely human, and in sidestepping the stuff that turns good biopics into great ones, “Chavez” is lesser than the legacy at its core, because it ignores all but the brightest spots. If it's seen at all, this film will be an introduction to a fascinatingly complex part of not just recent California history but a cultural icon, a civil rights leader not known as well as he probably should be. That the introduction is often only surface-level, without an ounce of subtlety, in the service of a slightly sanitized story over actual history is disappointing.

Video

“Cesar Chavez” has the sort of dirty, downtrodden, sweaty and almost soggy visuals one would expect from a film about the hard life of disenfranchised farmer workers in California’s often sweltering, and stinky, Central Valley. Shot on 35mm film, with predominately hand-held camerawork, a mix of excessively grainy film stocks—including high contrast black and white—and a dingy, downturned color palette of desaturated earth tones and the occasion bit of muted green, the 2.35:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer is not an especially pretty sight. Nor should it be. However, Lionsgate’s presentation, at least on an encoding and mastering level, is quite solid, without egregious post-process manipulation like edge enhancement or overzealous noise reduction, and detail quite fine—for standard definition, of course.

Audio

The bilingual menu lists the audio as English Dolby Digital 5.1, and includes options for subtitles in English or Spanish. Like the menu system of its DVD release, “Cesar Chavez” is actually a bilingual film. There may not be a 50-50 split between English and Spanish dialogue, but there’s enough that player-generated, subtitles appear at the bottom of the frame, above the lower letterbox bar, with regularity—obviously, whenever Spanish is spoken—by default. The mix itself is unexceptional, reserved by the nature of the rather talky subject matter. The sporadic speeches, in front of frenzied crowds, or clashes with protesters and picketers offer a greater sense of immersion and an energetic atmosphere, but are few and far between. Dialogue is cleanly delivered and the spare score by Michael Brook has reasonable clarity within the confines of lossy audio.

Extras

Nada. Although a bonus UltraViolet digital copy of the film is also included in the package. The disc offers the following pre-menu bonus trailers for: - “The Legend of Hercules” (1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen; 1 minute 38 seconds). - “Gimme Shelter” (2.35:1 anamorphic widescreen; 1 minute 33 seconds). - “Instructions Not Included” (1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen; 1 minute 35 seconds). - “Pulling Strings” (2.35:1 anamorphic widescreen; 1 minute 10 seconds). - “Spare Parts” (1.85:1 anamorphic widescreen; 1 minute 20 seconds). - “EPIX” promo (2.40:1 anamorphic widescreen; 1 minute 35 seconds). - “Take Part” promo (1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen; 1 minute 38 seconds).

Overall

I don’t doubt the intentions of those responsible for bringing the life of César Chávez to screen; surely they were noble—perhaps to a fault. The problem with this by-the-numbers biopic is two-fold. The rote, rigid structure has the plot often beats behind the audience, who’ve likely seen the same type of underdog story before—albeit, of course, with major and minor details changed for different historical figures and time periods. The result is a bland and predictable film that’s rarely more than a surface level examination. Almost like a highlight reel, if you will. On a larger level though, my issue with “Cesar Chavez” stems from its pick-and-choose approach of a man's personality and history, and general whitewashing of a vastly more complex figure. Chavez was a noble man, who said and did what he through was right, in the service of others, often sacrificing his own self and health. But he was hardly a saint, and this film comes close to canonizing him for a cause. “Cesar Chavez” offers a questionable overview of a figure little known, even less respected, outside of a California. I’m not sure a film like “Chavez” assists in bringing the man’s legacy into the mainstream; the blandness makes it less interesting, and the half truths sprinkled throughout make it bad history. On the other hand, it's at least watchable for the performances, which are good to great almost all around, and the production design and cinematography, which lend a punchy period look. Lionsgate’s DVD offers solid video and agreeable audio, within the realm of standard definition, but no extras.

|

|||||

|