|

|

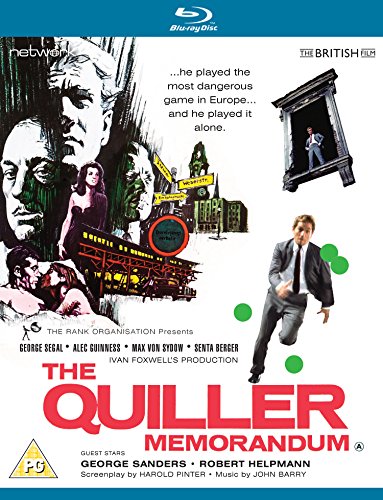

Quiller Memorandum (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (5th August 2014). |

|

The Film

The Quiller Memorandum (Michael Anderson, 1966) The Quiller Memorandum (Michael Anderson, 1966)

Adapted from the novel The Berlin Memorandum, by Elleston Trevor (writing under the pseudonym of Adam Hall), The Quiller Memorandum (Michael Anderson, 1966) focuses on the German experience after the Second World War. An American agent, Quiller (George Segal), is instructed by his British handler, Pol (Alec Guinness), to discover the location of the base of operations of a neo-Nazi group responsible for the murder of Quiller’s predecessor. During this adventure, he meets and falls in love with Inge (in the novel, Inga) Lindt (Senta Berger), a schoolteacher, and is captured by Oktober (Max von Sydow), seemingly a high-ranking member of the neo-Nazi organisation that Quiller is investigating. The film was scripted by Harold Pinter. The novel on which it is based, The Berlin Memorandum (first published in 1965), was the first in a long-running series by former RAF pilot Trevor that featured Quiller; Trevor wrote nineteen Quiller books in total, the last being Quiller Balalaika, published posthumously in 1996 (Trevor died in 1995). All of the Quiller novels are written in the first-person, and the lonely, isolated Quiller is described as a veteran of the Second World War who, during his operations, refuses to carry a firearm and insists on working alone. He also has a strong, proven resistance to methods of interrogation. By contrast with Ian Fleming’s Bond novels, the Quiller books largely take place in unfriendly and unromantic terrain. In The Special Branch: The British Spy Novel, 1890-1980 (1980), LeRoy Panek notes that Trevor ‘takes up the mantle of Ian Fleming’ but ‘far surpasses Fleming in craftsmanship and intelligence’; the Quiller books mimic ‘Len Deighton in up-dating the hard-boiled hero to fit the role of a British spy in the sixties’ and, ‘like other writers after mid-century, hurls a few brickbats at the concept of the institution, and, out of the best of motives, he gives his readers a surfeit of psychology’ (258). In adapting the novel to screen, the protagonist’s nationality was changed from British to American. In the novel, Quiller works for the Bureau, an enigmatic organisation that, officially, doesn’t exist and seems to be even more covert than MI5. The primary purpose of the Bureau (as stated in The Berlin Memorandum) was to investigate and hamper the rebirth of German fascism after the Second World War. (Operatives for the Bureau always have the option of refusing the missions with which they are presented.) The identity of the organisation that Quiller works for remains ambiguous in the film adaptation. Pinter’s script was praised by The Daily Telegraph for its ‘slightly surrealistic dialogue’ (quoted in Britton, 2005: 137). In Thrillers (1999), Martin Rubin suggests that the film is ‘notable’ for Pinter’s ‘barbed dialogue, which reflects the duplicity of espionage by charging the most banal utterances with layers of unspoken irony and menace’ (135). Rubin also allies The Quiller Memorandum with what he calls the ‘anti-Bond’ spy films such as The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (Martin Ritt, 1965) and The Ipcress File (Sidney J Furie, 1965). These films ‘sought to differentiate themselves from the Bonds by depicting espionage in a grimmer and more realistic light, although with a sense of irony and a lack of moral/patriotic certitude’ (ibid.: 133). In their preoccupation with deception and the work of double-agents (or at least, enemies who present themselves as allies), the films ‘reflected the treason scandals that had recently rocked the British spy establishment, culminating in’ Kim Philby’s defection in 1963 (ibid.). Ring of Spies (Robert Tronson, 1964), for example, recently released on DVD by Network (see our review here), offered an accurate account of the Portland affair of 1961, whilst at the climax of The Ipcress File intelligence agent Harry Palmer (Michael Caine) discovers that one of his superiors is a double-agent who is working for the enemy.  A recurring feature of the ‘anti-Bond’ spy film is ‘a sharper paranoid edge’ in which ‘[t]he field of anxiety is widened’ (Rubin, op cit.: 136). In these films, the ‘agent usually has to contend with dangers emanating not only from the other side but also from his own, which is riddled with traitors and/or is using him as an expendable pawn in a dirty game’ (ibid.). In these scenarios, the protagonist is depicted as ‘a man in the middle’ who is ‘caught between two or more sides’; his priority becomes ‘not finding the secret or winning the cold war but simply staying alive’ (ibid.). Rubin illustrates this concept by describing the sequence in The Quiller Memorandum in which Pol tries to explain the situation in West Germany to Quiller, using two ashtrays and a peanut. One ashtray is used to represent the neo-Nazi group; the other is used to represent the bureau. Quiller, of course, is the smaller peanut in between the two. ‘Let me put it this way’, Pol explains to Quiller: ‘There are two opposing armies drawn up on the field [he manoeuvres the ashtrays]. But there’s a heavy fog. They can’t see each other. Only the want to, of course, very much. You [the peanut] are in the gap between them. You can just see us. You can just see them. Your mission is to get near enough to see them to signal their position to us, so giving us the advantage. But if, in signalling their position to us, you inadvertently signal our position to them, it is they who will gain a very considerable advantage. That’s where you are, Quiller: in the gap’. At the end of the demonstration, Pol ‘impassively pops the peanut into his mouth and swallows it’ (ibid.). This focus on spycraft as a ‘game’ was something that, Steven H Gale suggests, was largely absent in the source novel and added by Pinter (Gale, 2003: 136). A recurring feature of the ‘anti-Bond’ spy film is ‘a sharper paranoid edge’ in which ‘[t]he field of anxiety is widened’ (Rubin, op cit.: 136). In these films, the ‘agent usually has to contend with dangers emanating not only from the other side but also from his own, which is riddled with traitors and/or is using him as an expendable pawn in a dirty game’ (ibid.). In these scenarios, the protagonist is depicted as ‘a man in the middle’ who is ‘caught between two or more sides’; his priority becomes ‘not finding the secret or winning the cold war but simply staying alive’ (ibid.). Rubin illustrates this concept by describing the sequence in The Quiller Memorandum in which Pol tries to explain the situation in West Germany to Quiller, using two ashtrays and a peanut. One ashtray is used to represent the neo-Nazi group; the other is used to represent the bureau. Quiller, of course, is the smaller peanut in between the two. ‘Let me put it this way’, Pol explains to Quiller: ‘There are two opposing armies drawn up on the field [he manoeuvres the ashtrays]. But there’s a heavy fog. They can’t see each other. Only the want to, of course, very much. You [the peanut] are in the gap between them. You can just see us. You can just see them. Your mission is to get near enough to see them to signal their position to us, so giving us the advantage. But if, in signalling their position to us, you inadvertently signal our position to them, it is they who will gain a very considerable advantage. That’s where you are, Quiller: in the gap’. At the end of the demonstration, Pol ‘impassively pops the peanut into his mouth and swallows it’ (ibid.). This focus on spycraft as a ‘game’ was something that, Steven H Gale suggests, was largely absent in the source novel and added by Pinter (Gale, 2003: 136).

In adapting the novel, Pinter also removed the importance of a character named Zossen, who is used as ‘bait’ to lure Quiller into the trap in which he finds himself, and another character, Dr Solomon Rothstein, whose murder plays an important role in the novel’s plot. In removing these elements, Pinter threw greater focus on the move/counter-move game of cat-and-mouse and the power plays between Quiller and Oktober: caught between the Bureau and Oktober’s group, Quiller (the peanut in the middle of two ashtrays) is captured and released, escapes and is captured again. Pinter’s reductive approach to the techniques of spycraft and the intricacies of the political situation delineated in the novel reputedly caused conflict between Pinter and Elleston Trevor (see Gale, 2003: 136). Trevor also disagreed with the casting of George Segal as Quiller, though Pinter felt Segal was absolutely right for the role (ibid.: 138). In 1994, after being approached for an interview by Christopher Hudgins, Trevor refused to discuss the film, claiming that Pinter had ‘destroyed the kernel of his book’ (ibid.). Pinter, in response, asserted that The Quiller Memorandum was the only adaptation on which he had worked that had not been supported by extensive discussions between Pinter and the author of the source material (ibid.).  Joanne Klein argued that Pinter’s script for The Quiller Memorandum was the worst kind of ‘hack writing for popular markets’ and negated much of the ‘problematic complexity and introversion’ of the source novel’s first-person narrative (quoted in ibid.). Pinter, for example, removed the suggestion that as a nine year old child, Inga/Inge Lindt had been in Hitler’s bunker when he committed suicide. In the novel, her worship of Hitler leads, after the war, to her becoming involved with the neo-Nazi group Phonix. When Quiller meets her, Inga/Inge is conflicted about her involvement with Phonix and wants to disassociate herself from them. Much of this is left ambiguous within Pinter’s script: the neo-Nazi group is never named, and the precise relationship between Inga/Inge and Oktober (and the other neo-Nazis) is never explained – nor are her reasons for allying herself with Oktober’s group. Quiller appears not to be aware of Inge’s collusion with the enemy he is hunting until the end of the film, when he says goodbye to her at the school at which she works (which in the novel is named as the Star of David School); unable (or unwilling) to do anything about Inge, who most certainly will continue spreading her ideology to the students in her care, Quiller walks away from her (and us), disappearing into the distance in a long take. Within this schema, Gale argues, Pinter retains very little of the source novel other than the ‘general idea of a resurgence of Nazism, the figure of Oktober and the grilling scene, the shadowing’ of Quiller after he ‘escapes’ from Oktober’s lair, ‘and the bomb under the car’ that Quiller uses as a distraction (2003: 136). Joanne Klein argued that Pinter’s script for The Quiller Memorandum was the worst kind of ‘hack writing for popular markets’ and negated much of the ‘problematic complexity and introversion’ of the source novel’s first-person narrative (quoted in ibid.). Pinter, for example, removed the suggestion that as a nine year old child, Inga/Inge Lindt had been in Hitler’s bunker when he committed suicide. In the novel, her worship of Hitler leads, after the war, to her becoming involved with the neo-Nazi group Phonix. When Quiller meets her, Inga/Inge is conflicted about her involvement with Phonix and wants to disassociate herself from them. Much of this is left ambiguous within Pinter’s script: the neo-Nazi group is never named, and the precise relationship between Inga/Inge and Oktober (and the other neo-Nazis) is never explained – nor are her reasons for allying herself with Oktober’s group. Quiller appears not to be aware of Inge’s collusion with the enemy he is hunting until the end of the film, when he says goodbye to her at the school at which she works (which in the novel is named as the Star of David School); unable (or unwilling) to do anything about Inge, who most certainly will continue spreading her ideology to the students in her care, Quiller walks away from her (and us), disappearing into the distance in a long take. Within this schema, Gale argues, Pinter retains very little of the source novel other than the ‘general idea of a resurgence of Nazism, the figure of Oktober and the grilling scene, the shadowing’ of Quiller after he ‘escapes’ from Oktober’s lair, ‘and the bomb under the car’ that Quiller uses as a distraction (2003: 136).

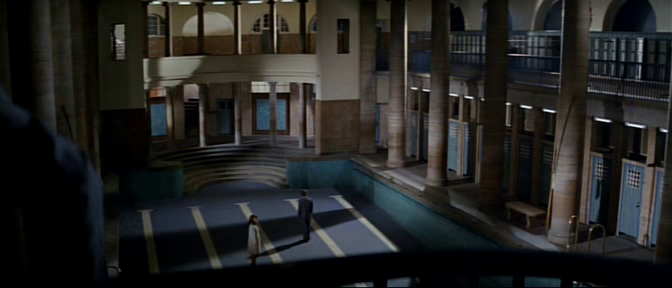

However, Pinter also added elements to the narrative, including the opening sequence depicting the murder of Quiller’s predecessor, Kenneth Lindsey Jones. Jones is shown walking along a deserted street towards a telephone box, which is positioned on the left hand side of the frame (Jones walks towards the camera on the right hand side of the frame). However, as he enters the telephone box, he is shot dead. The composition is repeated later in the film when Quiller, having been released by Oktober (in the hopes Quiller will lead Oktober’s group to the Bureau’s headquarters), walks slowly along the same street, towards the same telephone box (framed in exactly the same way). However, approaching the telephone box Quiller hesitates and, instead of entering it, walks away, followed by Oktober’s agents. Pinter also added a slightly surreal sequence in which Quiller and Inga meet with a former associated of Inga’s who, Inga claims, knows the location of Oktober’s base of operations. The meeting is surreal for its location: it takes place at the bottom of a huge indoor swimming pool that has been drained.    Other touches were added by Pinter, including the juxtaposition of the murder of Kenneth Lindsey Jones in West Berlin with the discussion, in a plush gentlemen’s club in London, between two of Pol’s superiors, Gibbs (George Sanders) and Rushington (Robert Flemyng). Gibbs and Rushington casually discuss the execution of Jones whilst eating, in the same tone of voice as they enquire about the quality of one another’s lunches. ‘Shame about KLJ’, Gibbs observes, before asking Rushington, ‘What’s your lunch’. ‘Pheasant’, Rushington replies. ‘That should be rather good. Is it?’ Gibbs asks. ‘It is, rather, yes’, Rushington asserts. Pinter’s script suggests veiled contempt for these figures of authority, for whom the agents on the ground are little more than pawns – and whose deaths merit little more than a passing notice during an expensive lunch. When Quiller’s body is dumped by the river (Quiller believes himself to have been the victim of a failed attempt on his life, but it seems that Oktober is keeping him alive so that Quiller might lead Oktober to the Bureau’s headquarters), Pinter once again cuts to Gibbs and Rushington making small talk at their club, discussing their invitations for the Lord Mayor’s Midsummer Banquet – again demonstrating the lack of concern these figures of authority have for the agents under their command. Like W H Auden, Steven H Gale notes, Pinter ‘recognizes the close proximity of the ordinary with violence’ (2003: 141). Other touches were added by Pinter, including the juxtaposition of the murder of Kenneth Lindsey Jones in West Berlin with the discussion, in a plush gentlemen’s club in London, between two of Pol’s superiors, Gibbs (George Sanders) and Rushington (Robert Flemyng). Gibbs and Rushington casually discuss the execution of Jones whilst eating, in the same tone of voice as they enquire about the quality of one another’s lunches. ‘Shame about KLJ’, Gibbs observes, before asking Rushington, ‘What’s your lunch’. ‘Pheasant’, Rushington replies. ‘That should be rather good. Is it?’ Gibbs asks. ‘It is, rather, yes’, Rushington asserts. Pinter’s script suggests veiled contempt for these figures of authority, for whom the agents on the ground are little more than pawns – and whose deaths merit little more than a passing notice during an expensive lunch. When Quiller’s body is dumped by the river (Quiller believes himself to have been the victim of a failed attempt on his life, but it seems that Oktober is keeping him alive so that Quiller might lead Oktober to the Bureau’s headquarters), Pinter once again cuts to Gibbs and Rushington making small talk at their club, discussing their invitations for the Lord Mayor’s Midsummer Banquet – again demonstrating the lack of concern these figures of authority have for the agents under their command. Like W H Auden, Steven H Gale notes, Pinter ‘recognizes the close proximity of the ordinary with violence’ (2003: 141).

As Gale notes, the film places in juxtaposition the Olympic Stadium built by the Nazis for the Olympic Games in 1936 (the site of the first meeting between Quiller and Pol; ‘Certain well-known personalities used to stand right up there’, Pol tells Quiller, pointing to the ‘Fuhrer’s box’), and the school in which Inga works (and secretly spreads her Nazi ideology). As Gale notes, the ‘link between these two worlds is the line “atrocity begins in the mind”’, which suggests a causative link ‘from the playground to the gas chamber’ (ibid.). Evil is depicted as profoundly insidious. During Quiller’s briefing, Pol tells Quiller, that things are ‘getting a bit out of hand in Berlin. Quite a tough bunch. Nazi from top to toe, in the classic tradition. But not just the remains of the old lot, oh no. There’s quite a bit of new blood. Youth. Firm believers. Very dangerous. It wouldn’t do to underestimate them [….] Difficult to pinpoint. Nobody wears a brown shirt now, you see. No banners. Consequently, they’re difficult to recognise. They look like anybody else’. Quiller learns this lesson when he gradually realises that the seemingly harmless, innocent schoolteacher Inga, who during her first meeting with Quiller denounced the neo-Nazis, is allied with Oktober. Inga, Quiller is told, has replaced another teacher, Steiner, who was recently revealed to be a Nazi war criminal in hiding. During her introduction to Quiller, Inga reminds him that the new Nazis ‘don’t call themselves that anymore’. Later, Quiller foregrounds the insidious approach of the new brand of Nazism that he is confronting, telling Inga, ‘They [the neo-Nazis] want to infiltrate themselves into the mind of the country, over a period of years; but they’re not in any kind of hurry this time’. Andrew Sarris suggested that the thirteen films Michael Anderson had made prior to The Quiller Memorandum were ‘so undistinguished’ in terms of his directorial signature ‘that two conclusions are unavoidable’: ‘Pinter was the true auteur of The Quiller Memorandum’; and ‘Pinter found Anderson an ideal metteur-en-scene for his (Pinter’s) very visual conceits’ (quoted in Gale, 2009: 103). In William Baker’s book about Harold Pinter (2008), Baker notes that The Quiller Memorandum displays many of the preoccupations of Pinter’s work generally, though some of these are present in the source novel anyway: ‘resistance to authority; suspense; power play and the strength of women; plus moral ambiguity’ (67). Steven H Gale has suggested that Pinter may have been attracted to the novel owing to ‘a number of elements’, including ‘the theme of domination and the Hitler/Jew background’ (Gale, 2003: 135-6).  In later work, Pinter would show a more overt interest in the Holocaust; in this sense, The Quiller Memorandum ‘anticipates Pinter’s subsequent 1987-1988 adaptation’ of the novella Reunion (Fred Uhlman, 1971), which focuses on the friendship between Jewish doctor’s son Hans Schwartz and the aristocratic Conrad von Hohenfels in Stuttgart in 1932, ‘[i]n its concern with guilt, revenge and the past set in Germany’ (Baker, op cit.: 68). However, Gale also notes that The Quiller Memorandum’s central sequence, depicting Oktober’s interrogation of Quiller in the cellar of the neo-Nazi group’s base of operations, looks backwards to the short story ‘Kullus’, written by Pinter in 1949 – as do many of Pinter’s other texts, such as his adaptation of The Servant, which feature territorial battles waged by small groups of individuals in confined spaces (see Gale, 2003: 136). In later work, Pinter would show a more overt interest in the Holocaust; in this sense, The Quiller Memorandum ‘anticipates Pinter’s subsequent 1987-1988 adaptation’ of the novella Reunion (Fred Uhlman, 1971), which focuses on the friendship between Jewish doctor’s son Hans Schwartz and the aristocratic Conrad von Hohenfels in Stuttgart in 1932, ‘[i]n its concern with guilt, revenge and the past set in Germany’ (Baker, op cit.: 68). However, Gale also notes that The Quiller Memorandum’s central sequence, depicting Oktober’s interrogation of Quiller in the cellar of the neo-Nazi group’s base of operations, looks backwards to the short story ‘Kullus’, written by Pinter in 1949 – as do many of Pinter’s other texts, such as his adaptation of The Servant, which feature territorial battles waged by small groups of individuals in confined spaces (see Gale, 2003: 136).

Eddi Fiegel’s book about John Barry suggests that like The Ipcress File, The Quiller Memorandum offered ‘a more thoughtful approach’ to spycraft than the Bond imitations that proliferated during the mid-1960s (2012: np). The film, for Fiegel, ‘picked up on Harry Palmer’s sense of isolation and continued the theme of misplaced loyalties’ (ibid.). However, in his score for the film John Barry didn’t return to the motifs he had developed for The Ipcress File, approaching The Quiller Memorandum as ‘a completely new project’: although the ‘feel [of the music] was still Eastern European, […] the sentiment behind it was different’ (ibid.). Pinter encouraged Barry, in developing his score, not to focus on the darkness of the theme of the neo-Nazi threat, but instead to imbue the music with an ‘innocent childlike thing which goes totally against the picture’, underscoring the theme of the indoctrination of young children with Nazi ideology (represented by Senta Berger’s schoolteacher in the fillm, who at the end of the picture goes unpunished and is allowed to continue teaching the children in her care). For Pinter, Barry claimed, The Quiller Memorandum ‘was all about the indoctrination of youth – how you created young Nazis. And there were all those sequences in the film of lines of kids coming out of the school. So I said, “Let’s play this innocence up against this possibly recurring nightmare,” and I wrote that melody that was based on an eighteenth-century lullaby’ (Barry, quoted in ibid.). Barry asserted that this counter-scoring ‘worked beautifully’ and ‘gave the film a haunting, dramatic quality which kept it together’ (quoted in ibid.). Interestingly, when The Quiller Memorandum was released in West Germany, the American distributors (at the behest of Dr Ernest Krueger, the head of the West German film industry’s Voluntary Self-Control Board) cut all references to the neo-Nazi ideology of Oktober’s group, leaving West German audiences with the impression that the villains were in fact Communists (Gale, 2003: 138). Krueger claimed that the suggestion that a neo-Nazi terror group may be operating within West Germany was both ‘unrealistic’ and ‘inopportune because of our image toward East Germany and the Communists, who are raising charges of neo-Nazism against us at the moment’ (quoted in ibid.). The Quiller Memorandum wasn’t the only screen adaptation of the Quiller novels: it was followed in 1975 by the BBC series Quiller, in which Quiller was played by Michael Jayston. Of the thirteen episodes of Quiller, only one (‘Tango Briefing’) was adapted from one of Trevor’s novels, and was scripted by Trevor himself. The film here is presented uncut, with a running time of 104:50.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1; the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The presentation of the film is unstable, demonstrating some problems that seem to have been caused in the telecine. There is a fairly consistent flicker/pulsing effect, with brightness levels seeming to fluctuate. This is particularly noticeable during the sequences set at night. Also noticeable throughout the film (but, again, especially during low light sequences) is something that appears to be scanner noise (rather than natural film grain). Set at night, the opening sequence, depicting the murder of KLJ, evidences both the scanner noise and the flicker. Detail is a step up from the DVD (for this reason, the obvious soft focus close-ups of Senta Berger now seem to stick out like a sore thumb against the rest of the photography), but only just, and contrast is weak throughout. It’s not a terrible presentation, but put alongside Network’s impressive Blu-ray release of The Ipcress File, one can’t help but feel a little disappointed by this Blu-ray. If this disc is an improvement on the DVDs that are available, it’s by default: the presentation of the film on the various DVDs that have been released was very poor. This Blu-ray contains the best presentation of The Quiller Memorandum on the market, but that’s far from saying it’s ideal, and the issues here could probably only be addressed by a new scan of the film materials. (NB. Current screen grabs are for illustration purposes only and are not intended to reflect the quality of Network’s Blu-ray releases. More representative screen grabs will be added in a few days.)

Audio

The disc contains a lossless LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is clear throughout and demonstrates good range. Optional English subtitles (for the Hard of Hearing) are included.

Extras

The disc includes a number of archival interviews, with Extras: - George Segal (4:18) - Alec Guinness (5:25) - Senta Berger (5:02) - Max Von Sydow (3:56) - Michael Anderson (4:53) - Ivan Foxwell (10:31) These are interesting and help to place the film in context, but as can be gauged by the running times, they’re very brief. The disc also includes the film’s original theatrical trailer (3:08), and some textless material (2:40), actually the film’s opening sequence sans titles and sound. Finally, the disc includes a number of image galleries: - Production image gallery (8:17) - Behind the scenes gallery (9:53) - Portrait image gallery (4:56) - Promotional image gallery (0:41)

Overall

In a 1973 diary entry, Alec Guinness referred to the film as ‘the unmemorable Quiller Memorandum’, later describing it (after revisiting it on television in 1980) as ‘a very cliché-ridden story’ with a weak script by Pinter (quoted in Read, 2005: 386). Guinness’ feelings towards the film seem to be echoed in the feelings of the author of the source novel, Elleston Trevor. However, these criticisms of The Quiller Memorandum are far from universal. Some critics feel that the film is underrated. In a 1973 diary entry, Alec Guinness referred to the film as ‘the unmemorable Quiller Memorandum’, later describing it (after revisiting it on television in 1980) as ‘a very cliché-ridden story’ with a weak script by Pinter (quoted in Read, 2005: 386). Guinness’ feelings towards the film seem to be echoed in the feelings of the author of the source novel, Elleston Trevor. However, these criticisms of The Quiller Memorandum are far from universal. Some critics feel that the film is underrated.

Although the film’s approach to spycraft is reductive, largely due to the changes Pinter made to the source novel, there is much else to admire here. Pinter’s dialogue sparkles, and for the most part it is delivered expertly. The film also makes interesting use of architecture, from Werner’s Olympic Stadium to the school in which Inga teaches (actually the Free University’s Henry Ford building); from the cramped cellar and underground tunnels that Oktober’s group use as their headquarters, to the Bureau’s base of operations in a partially-constructed floor of the Europa Center. The presentation of the film on this disc leaves much room for improvement, though by default it’s arguably the best presentation of the film currently available. The lossless audio is bonus, but this is mitigated by the problematic transfer – and the issues here (the near-constant flicker, and the apparent scanner noise) seem a product of the scan, probably present in other presentations of the film but arguably emphasised by the HD presentation on this Blu-ray, and could be corrected by going back to the original film elements. Nevertheless, in terms of visual detail this Blu-ray is a reasonable improvement over the various DVDs. There is also a good range of contextual material here (equal to Network’s previous DVD release). References: Baker, William, 2008: Harold Pinter. London: Continuum Britton, Wesley Alan, 2005: Beyond Bond: Spies in Fiction and Film. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers Fiegel, Eddi, 2012: John Barry: A Sixties Theme – From James Bond to ‘Midnight Cowboy’. London: Faber & Faber Gale, Steven H, 2003: Sharp Cut: Harold Pinter’s Screenplays and the Artistic Process. University Press of Kentucky Gale, Steven H, 2009: ‘Harold Pinter, screenwriter: an overview’. In: Raby, Peter (ed), 2009: The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter. Cambridge University Press: 88-104 Panek, LeRoy, 1980: The Special Branch: The British Spy Novel, 1890-1980. Bowling Green University Popular Press Read, Piers Paul, 2005: Alec Guinness. London: Simon & Schuster Rubin, Martin, 1999: Thrillers. Cambridge University Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:  >

|

|||||

|