|

|

Capricorn One (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (15th August 2014). |

|

The Film

Capricorn One (Peter Hyams, 1977)  One of the wave of paranoid conspiracy thrillers that proliferated after the breaking of the Watergate scandal (along with films such as Alan J Pajula’s The Parallax View, 1974, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, also 1974, and Three Days of the Condor, 1975), Peter Hyams’ Capricorn One (Peter Hyams, 1977) tapped into the zeitgeist of government conspiracy and the waning interest in the lunar landings (the last of which took place in 1972). These films, Stephen Prince has suggested, offered a turning away from ‘the celebration of outlaw heroes in late-sixties’ pictures such as Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), and were ‘[m]ore despairing about the prospects for democratic society’, marking them as ‘films in the shadow of Watergate’ (2000: 64). The films foregrounded ‘governmental corruption and conspiracy’, and the stories they told offered ‘parables of defeated heroes in which shadowy cartels and power brokers maintained pervasive social control’ (ibid.). In examining these issues, the paranoid conspiracy thrillers also marked themselves as different from the ‘Spielberg-Lucas feel-good science fiction and fantasy’ pictures that were becoming dominant during the late-1970s (ibid.). One of the wave of paranoid conspiracy thrillers that proliferated after the breaking of the Watergate scandal (along with films such as Alan J Pajula’s The Parallax View, 1974, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, also 1974, and Three Days of the Condor, 1975), Peter Hyams’ Capricorn One (Peter Hyams, 1977) tapped into the zeitgeist of government conspiracy and the waning interest in the lunar landings (the last of which took place in 1972). These films, Stephen Prince has suggested, offered a turning away from ‘the celebration of outlaw heroes in late-sixties’ pictures such as Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), and were ‘[m]ore despairing about the prospects for democratic society’, marking them as ‘films in the shadow of Watergate’ (2000: 64). The films foregrounded ‘governmental corruption and conspiracy’, and the stories they told offered ‘parables of defeated heroes in which shadowy cartels and power brokers maintained pervasive social control’ (ibid.). In examining these issues, the paranoid conspiracy thrillers also marked themselves as different from the ‘Spielberg-Lucas feel-good science fiction and fantasy’ pictures that were becoming dominant during the late-1970s (ibid.).

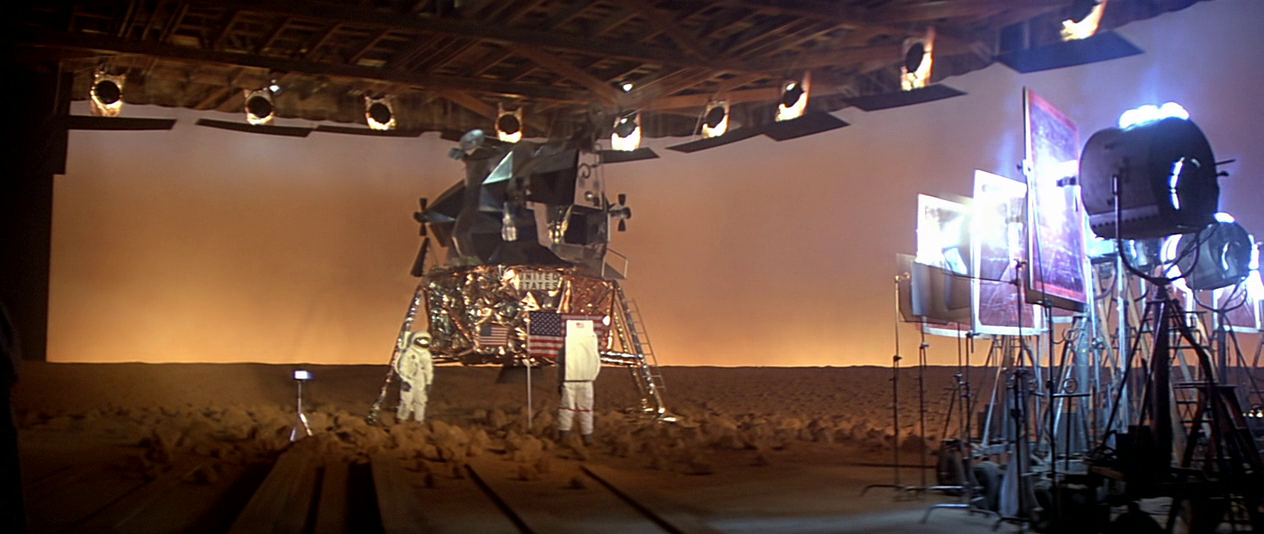

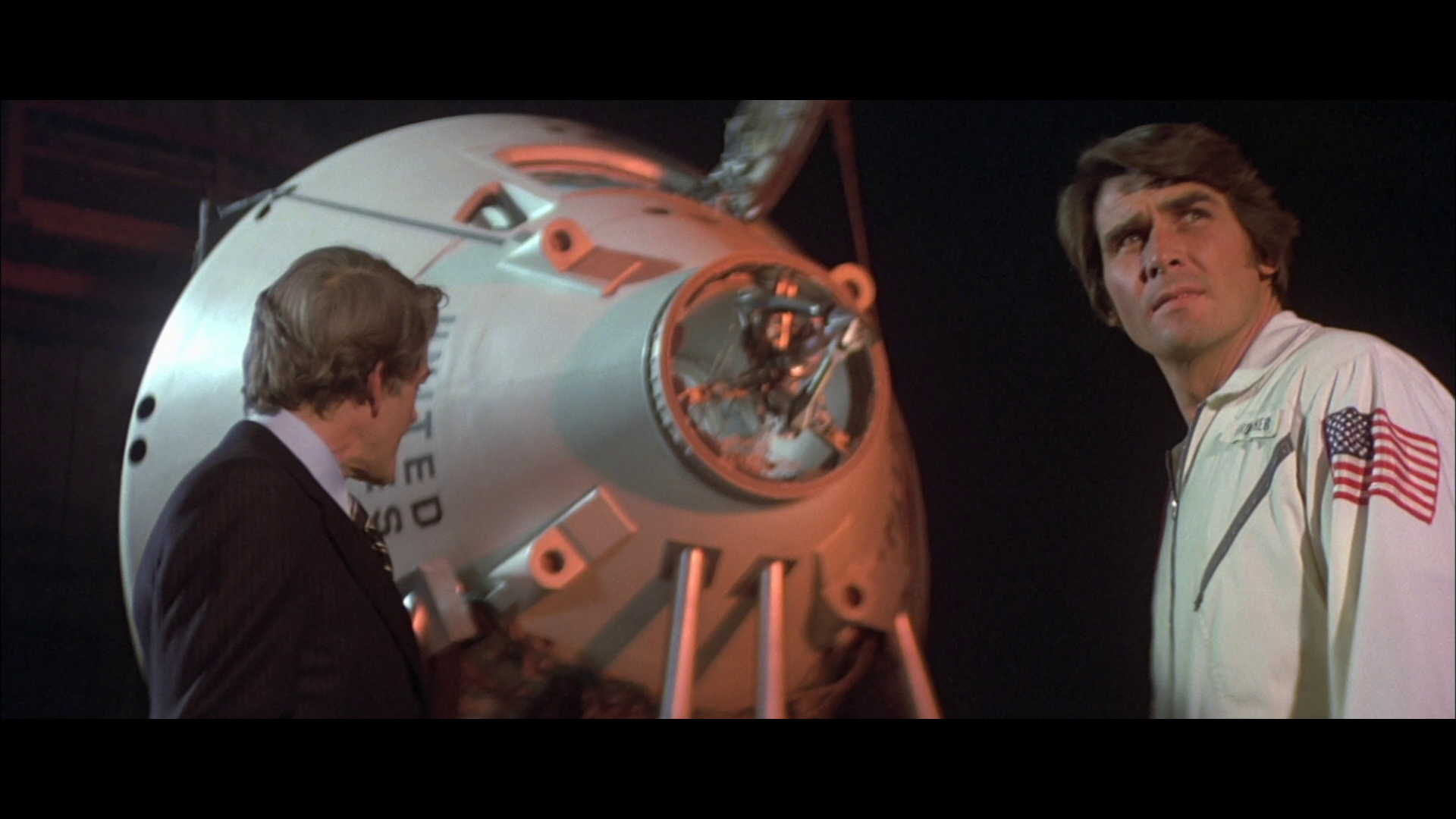

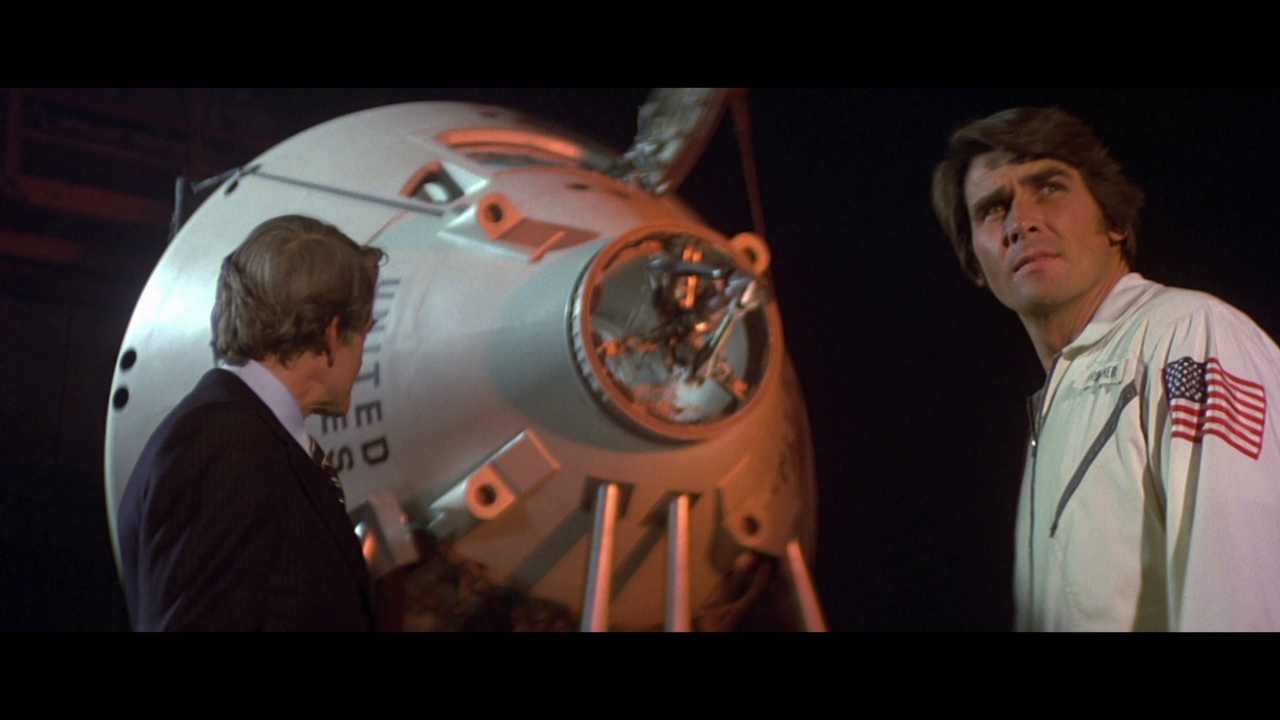

Capricorn One’s narrative focuses on a manned landing on Mars which is revealed to be a hoax, with the landing simulated on a sound stage in a television studio, and the crew of the craft coaxed into taking part in the conspiracy after threats are made towards the lives of their families. In his discussion of American cinema ‘in the shadow of Watergate and Vietnam’, David A Cook suggests that in its exploration of a plot to deceive the public using the medium of television, Capricorn One was also one of a spate of films that evidenced the fact that ‘the public was becoming as cynical about the media as it was of other national institutions’; other films which focus on this theme include Sidney Lumet’s Network (1976) and The China Syndrome (James Bridges, 1979) (Cook, 2000: 201). The film opens at the launch of Capricorn One, which is attended by Governor Hollis Peaker (David Huddleston), a supporter of the space mission, and Vice President Price (James Karen). At the last minute, the crew of the spacecraft – Charles Brubaker (James Brolin), John Walker (O J Simpson) and Peter Willis (Sam Waterston) – are ushered out of the craft and removed from the site. They are told by Dr Kelloway (Hal Holbrook), the scientific overseer of the Capricorn One mission, that owing to a faulty life support system, the mission was doomed to failure. Kelloway instead intends to fabricate the landing on Mars, using a carefully-built set on a sound stage; the astronauts will film their scenes on this set, and these will then be broadcast to an unknowing public. The conspiracy is limited in scope: only a handful of people seem to know about Kelloway’s plan. (The President and Vice President are unaware of Kelloway’s scheme, and it is ambiguous as to whether Governor Peaker, an ardent proponent of the space programme, is involved in the conspiracy.)  When Elliot Whitter (Robert Walder), a NASA technician, notices that the transmissions from the astronauts seem to be coming from somewhere in the United States, he is told by Kelloway and another senior staff member that his monitor is malfunctioning. However, Whitter conducts some experiments in his own time, which verify his findings, and relays this information to a friend, journalist Robert Caulfield (Elliott Gould). Caulfield attempts to investigate, but his friend Whitter soon disappears, and the woman who now inhabits Whitter’s apartment claims to have lived there for a number of years – something which Caulfield knows to be false. A comment by Brubaker, who struggles with his involvement in the conspiracy, to his wife (Brenda Vaccaro) during one of the astronauts’ transmissions, makes Caulfield even more suspicious, and he decides to investigate. Meanwhile, the re-entry shields on the real spacecraft malfunction, causing the capsule to vaporise. NASA declare the astronauts dead, and fearing for their lives Brubaker, Walker and Willis stage an escape from the facility in which they are being held, fleeing across the Nevada desert. They are chased by faceless agents of the conspiracy, in black helicopters, but Caulfield deduces what has happened and hires eccentric crop duster Albain (Telly Savalas) to help him scour the desert for signs of the astronauts. When Elliot Whitter (Robert Walder), a NASA technician, notices that the transmissions from the astronauts seem to be coming from somewhere in the United States, he is told by Kelloway and another senior staff member that his monitor is malfunctioning. However, Whitter conducts some experiments in his own time, which verify his findings, and relays this information to a friend, journalist Robert Caulfield (Elliott Gould). Caulfield attempts to investigate, but his friend Whitter soon disappears, and the woman who now inhabits Whitter’s apartment claims to have lived there for a number of years – something which Caulfield knows to be false. A comment by Brubaker, who struggles with his involvement in the conspiracy, to his wife (Brenda Vaccaro) during one of the astronauts’ transmissions, makes Caulfield even more suspicious, and he decides to investigate. Meanwhile, the re-entry shields on the real spacecraft malfunction, causing the capsule to vaporise. NASA declare the astronauts dead, and fearing for their lives Brubaker, Walker and Willis stage an escape from the facility in which they are being held, fleeing across the Nevada desert. They are chased by faceless agents of the conspiracy, in black helicopters, but Caulfield deduces what has happened and hires eccentric crop duster Albain (Telly Savalas) to help him scour the desert for signs of the astronauts.

The film makes an attempt to engage with the politics of investing in a space programme. (The launch of Capricorn One, we are told, has cost four billion dollars.) Peaker’s anger is piqued at the absence of the President. In his place, Vice President Price displays a nonchalance towards the proceedings: at one point, Peaker catches Price looking at the derriere of a female employee, rather than the launch, through the commemorative binoculars with which he has been presented. ‘It’s that big, tall, white thing over there’, Peaker tells Price, ‘Can’t miss it’. When Peaker questions Price over the absence of the President, Price assures Peaker that the President is ‘interested’ in the programme. ‘I am interested in a lot of things, including my wife’s bridge game. That’s not the same as supporting something’, Peaker reminds Price. ‘Hollis, there are a number of people who feel that we have problems right here on Earth that merit our attention before we spend billions of dollars on outer space’, Price responds. ‘There are a number of people who feel that there are no more pressing problems than our declining position in world leadership’, Peaker hits back.  During his conversation with the astronauts, Kelloway highlights the public’s growing apathy towards space exploration: when John Glenn landed on the moon, Kelloway reminds the others, television audiences grumbled because repeats of I Love Lucy were cancelled. Then people complained about the cost of the space programme. ‘How much does any dream cost, for Christ’s sake?’, Kelloway asks, ‘Since when is there an accountant for ideas?’ Who was at the launch of Capricorn One, Kelloway asks Brubaker and his colleagues, ‘The Vice President and his plump wife’ – not the President himself, as Peaker has already made clear. During his conversation with the astronauts, Kelloway highlights the public’s growing apathy towards space exploration: when John Glenn landed on the moon, Kelloway reminds the others, television audiences grumbled because repeats of I Love Lucy were cancelled. Then people complained about the cost of the space programme. ‘How much does any dream cost, for Christ’s sake?’, Kelloway asks, ‘Since when is there an accountant for ideas?’ Who was at the launch of Capricorn One, Kelloway asks Brubaker and his colleagues, ‘The Vice President and his plump wife’ – not the President himself, as Peaker has already made clear.

Kelloway is an interesting character, played with depth by Holbrook. His desire to fabricate the landing on Mars, so as to guarantee continued funding for space exploration, seems to be predicated on a profound idealism. The mission is under financial and political pressure to succeed, something which Kelloway suggests legitimates the conspiracy. Before the mission, he was told by the President to ‘make it good’, because the country ‘can’t afford a screw-up. And guess what, we had a screw-up: a first class, bona fide, made-in-America screw-up’. ‘What’s this all gonna solve?’, Brubaker asks. ‘It’ll keep something alive that shouldn’t die’, Kelloway says, ‘Before you all begin to moralise, you take a look around. You look at what we’ve done and how much we can do. You look at what we’ve meant to this country. Nobody gives a crap about anything anymore [….] There’s nothing more to believe in. Do you want to blow this whole thing open? God knows what it might do to everybody [….] Do you want to be the ones who give everyone another reason to give up?’ Brubaker’s response to this is to tell Kelloway, ‘If the only way to keep something alive is to become something I hate, I don’t know if it’s worth keeping alive’.  When Kelloway first reveals what has happened to the astronauts of the Capricorn One mission, he attempts to persuade them to side with him by using careful rhetoric, informing them that ‘we all want the same thing. We are not your enemy’, before reminding them of the times they (Kelloway and the astronauts, especially Brubaker) have shared together. The failure of the life support systems will give the President the excuse he needs to scrap the programme. (Willis interrupts Kelloway’s monologue with humour, declaring, ‘Hello, Dr Kelloway. Nice to see you. A funny thing happened on the way to Mars’.) ‘What if we say no?’, Brubaker asks. ‘I don’t know. Don’t say no’, Kelloway tells him. When this fails, Kelloway threatens the lives of the astronauts’ families, though given the limited scope of the conspiracy it is unclear whether this is a legitimate threat or simply a ploy to persuade the astronauts to co-operate. ‘Shit, this thing is out of my hands’, Kelloway says, deploying the classic salesman’s tactic of deflection and avoidance of responsibility, ‘You think it’s all a couple of looney scientists? It’s not. It’s bigger. There are people out there, forces out there, who have a lot to lose. They’re grown-ups. It’s gotten too big: it’s in the hands of grown-ups’. When Kelloway threatens the lives of the astronauts’ families, he couches it in vague, nebulous terms: ‘They’re on the plane together, God damn it. You want it in writing? There’s a device. It’s on the plane too’. When Kelloway first reveals what has happened to the astronauts of the Capricorn One mission, he attempts to persuade them to side with him by using careful rhetoric, informing them that ‘we all want the same thing. We are not your enemy’, before reminding them of the times they (Kelloway and the astronauts, especially Brubaker) have shared together. The failure of the life support systems will give the President the excuse he needs to scrap the programme. (Willis interrupts Kelloway’s monologue with humour, declaring, ‘Hello, Dr Kelloway. Nice to see you. A funny thing happened on the way to Mars’.) ‘What if we say no?’, Brubaker asks. ‘I don’t know. Don’t say no’, Kelloway tells him. When this fails, Kelloway threatens the lives of the astronauts’ families, though given the limited scope of the conspiracy it is unclear whether this is a legitimate threat or simply a ploy to persuade the astronauts to co-operate. ‘Shit, this thing is out of my hands’, Kelloway says, deploying the classic salesman’s tactic of deflection and avoidance of responsibility, ‘You think it’s all a couple of looney scientists? It’s not. It’s bigger. There are people out there, forces out there, who have a lot to lose. They’re grown-ups. It’s gotten too big: it’s in the hands of grown-ups’. When Kelloway threatens the lives of the astronauts’ families, he couches it in vague, nebulous terms: ‘They’re on the plane together, God damn it. You want it in writing? There’s a device. It’s on the plane too’.

Peter Hyams became interested in making the film owing to his work as a reporter for CBS, which led him to reflect on the lunar landings, stating that these momentous events ‘had almost no witnesses. And the only verification’ that they had taken place ‘came from a TV camera’ (quoted in De Monchaux, 2011: 257). The suggestion that the lunar landings had been faked, a conspiracy theory popularised in William Charles Kaysing’s 1974 book We Never Went to the Moon: America’s Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle, was given added credence by the Watergate scandal, which acted to undermine the credibility of the American government (see ibid.). Hyams wrote the screenplay that would evolve into Capricorn One in 1972. The script was originally given the greenlight by Warner Brothers in 1973, after the House Watergate hearings, though it was a long journey until the film was actually produced (by Lew Grade) (ibid.: 259). The New York Times commented that the scandal surrounding ‘Watergate may not have inspired “Capricorn One,” but it made its thesis more acceptable, its plot more credible and some of its content strangely prophetic’ (quoted in ibid.). Famously, Jean Baudrillard cited Capricorn One, in his 1991 essay ‘The Gulf War Did Not Take Place’, as an example of a film that foregrounds the kind of hyperreal simulation that Baudrillard argues has come to dominate the political landscape (Baudrillard, 1995: 61). Within the film, the simulation of the Mars landings, and the conspiracy which is built up around it, represents ‘a betrayal’ of the idealism associated with the Space Age (Benjamin, 2003: 104). Marina Benjamin suggests that in its cynical examination of the ways in which a media-generated spectacle may be used to deceive the population, Capricorn One offers an antidote to the ‘theme park culture’ that was beginning to dominate Hollywood and other aspects of popular culture (ibid.). The film also sets itself apart from many of the paranoid conspiracy thrillers of the 1970s; where many of these films, such as Alan J Pakula’s The Parallax View, focused on ‘political assassins or […] grand scheme[s] to seize the reins of government’, the conspiracy in Capricorn One is created by ‘a seemingly dedicated government scientist’, Kelloway, whose aim is to counteract the public’s waning interest in the space race so as to ensure continued government funding (Arnold, 2008: 105).  In Kelloway’s eyes, the conspiracy is necessitated by the unsuccessful collusion of government and business: corners cut by the private company contracted to provide the life support system for the spacecraft result in a life support system that, on closer inspection, is scheduled to fail two weeks into the flight. If this happens, and the astronauts die during the journey to Mars, or alternatively if the mission is cancelled in the wake of this news, the mission will be a disaster, and the US government will cut its funding towards future missions. Kelloway believes that the only way to ensure future government funding, and to maintain the general public’s interest in the space programme (thus also ensuring further funding), is to fake the landing on Mars. The spread of the conspiracy is apparently limited: only Kelloway and a small group of other NASA employees are aware of it. In light of this, it is unclear whether Kelloway’s threats towards the families of the astronauts, which he uses to cajole the astronauts into collaborating with him, are genuine or simply a form of bluster. Additionally, when the ship supposedly carrying the astronauts burns up on re-entry owing to faulty re-entry shields (another fault most likely caused by private contractors cutting corners) – an event which causes the astronauts to fear for their lives (will they be murdered to silence them?), thus provoking their escape attempt from the facility in which they are held – the film renders ambiguous the question as to whether or not Kelloway foresaw this, and whether or not the conspiracy from the beginning involved the murder of the astronauts. In Kelloway’s eyes, the conspiracy is necessitated by the unsuccessful collusion of government and business: corners cut by the private company contracted to provide the life support system for the spacecraft result in a life support system that, on closer inspection, is scheduled to fail two weeks into the flight. If this happens, and the astronauts die during the journey to Mars, or alternatively if the mission is cancelled in the wake of this news, the mission will be a disaster, and the US government will cut its funding towards future missions. Kelloway believes that the only way to ensure future government funding, and to maintain the general public’s interest in the space programme (thus also ensuring further funding), is to fake the landing on Mars. The spread of the conspiracy is apparently limited: only Kelloway and a small group of other NASA employees are aware of it. In light of this, it is unclear whether Kelloway’s threats towards the families of the astronauts, which he uses to cajole the astronauts into collaborating with him, are genuine or simply a form of bluster. Additionally, when the ship supposedly carrying the astronauts burns up on re-entry owing to faulty re-entry shields (another fault most likely caused by private contractors cutting corners) – an event which causes the astronauts to fear for their lives (will they be murdered to silence them?), thus provoking their escape attempt from the facility in which they are held – the film renders ambiguous the question as to whether or not Kelloway foresaw this, and whether or not the conspiracy from the beginning involved the murder of the astronauts.

As Gordon B Arnold notes, the film’s premise requires its audience to ‘easily accept the idea that vaguely defined interests within the American establishment would resort to conspiracy in order to maintain the status quo’ (op cit.: 107). Although only a handful of individuals are shown participating in the conspiracy, ‘the logic of the story’ demands the audience assume that ‘business, government, and military figures are implicated’ (ibid.). One of the film’s major contributions to the subgenre of conspiracy thrillers is the involvement of the media in maintaining the conspiracy that is at the heart of the film’s narrative: the picture’s ‘most significant idea […] is that nothing reported is necessarily the truth’ (ibid.). The Mars landing itself is a fiction; the news media outlets are not necessarily a direct part of the conspiracy, but they ‘are easily duped and are manipulated by the conspirators to further their special agenda’ (ibid.). Thus, the film suggests the ways in which ‘sinister forces can shape society’s beliefs, contorting reality for their own purposes’ (ibid.).

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The presentation of the film uses the AVC codec and consumes approximately 20Gb of a single-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The presentation of the film uses the AVC codec and consumes approximately 20Gb of a single-layered Blu-ray disc.

The presentation appears to be based on the same source as the ITV Blu-ray that was released in 2007, although the gamma levels seem to be slightly different: the presentation of the film on the Network Blu-ray is slightly brighter, with softer reds (resulting in more natural skin tones). The ITV Blu-ray has a more ‘contrasty’ appearance, and skin tones veer towards the red. Shadow detail seems to fare better on the new Network disc. However, the difference between the two releases is marginal, in terms of visible detail and the presence of organic film grain. The shots in the Nevada desert, presumably shot with the aperture fully stopped down, display a considerable amount of depth, but the sequences shot in interiors are less impressive – most likely a characteristic of the original photography. For example, some shots in low-light situations (and presumably with the aperture wide open) seem to exhibit a softness that would appear to be a characteristic of the lenses used during the shoot. It’s not a great presentation, but in the world’s of Old Sykes, ‘it’ll do’. A visual comparison of Network’s new Blu-ray with ITV’s older disc is at the bottom of this review.

Audio

One area where this disc is a noticeable improvement over the ITV disc is the audio, presented here via a lossless LPCM 2.0 stereo track (whereas the ITV disc contains a lossy Dolby Digital stereo track). The lossless track here is far more ‘punchy’ than the lossy track on the ITV disc, showing off Goldsmith’s score and the thunder of the helicopters during the climactic chase across the Nevada desert. However, given that the majority of the scenes are dialogue-based, there’s little room for this track to shine. Additionally, in a couple of sequences the dialogue seems to be mixed low, and there also seems to be some ‘clipping’ here and there. This may or may not be a product of the original sound recording. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes several featurettes. - ‘What If ? The Making of Capricorn One' (6:49, SD). This vintage production featurette is short and full of promotional fluff, but it’s interesting nonetheless. - 'On Set with Capricorn One' contains two entries: -- Desert Filming (38:21, SD). This is raw footage from the shoot in the desert. -- Studio Filming (4:07, SD). Raw footage from the shoot in the studio. Both of these are interesting but arguably non-essential, and could have benefited from some commentary over them or more judicious editing. Finally, the disc includes a gallery (4:05) of posters and on-set stills.

Overall

Capricorn One is an interesting conspiracy thriller: whilst paying some regard to the rollercoaster thrills of the blockbusters that were coming to dominate Hollywood in the mid-1970s, the film demonstrates a far more cynical worldview than most of those pictures. Kelloway is an idealist, and the film subtly depicts the corruption of the idealism of the Space Age. Where the film falls down, predominantly, is in its sop to the conventions of the action-based rollercoaster pictures: the extended chase scene that marks its climax, and the attempt on Caulfield’s life (his car is tampered with, resulting in a time-lapse rampage through the city streets which wouldn’t look out of place in a panoramic cinema theme park exhibit). Though the climax introduces Telly Savalas’ wonderful turn as crop duster Albain, in many ways it feels like too much of a step away from the interior nature of the conspiracy as outlined in the first half of the film: the sterile corridors and offices of the facility in which the astronauts are held, all in white and shot with wide-angle lenses to emphasise their emptiness. The scenes in which Kelloway outlines his plan to the astronauts work very well, largely thanks to Holbrook’s performance, but also owing to the prickly David Mamet-esque dialogue, which is laced with periphrasis, elision and repetition.   The sequence in which the landing on Mars is faked works very well, and includes a very impressive shot: a slow dolly away from the reflective visor of one of the astronauts to reveal the sound stage on which the ‘landing’ is taking place. Sadly, the photography elsewhere is often flat and unimpressive. This disc contains a good presentation of the film, on par with the previous Blu-ray release from ITV. There are some soft-looking shots which seem to be a product of the lenses used during the shooting of the film (these mostly appear in low-light scenes, which were most likely shot with the lens wide open). Sequences shot in daylight (with the lens fully stopped down) look much more impressive. In comparison with the ITV Blu-ray, this disc seems to show slightly different gamma levels: it looks slightly brighter, with softer contrast, and more natural skin tones. However, it’s almost certainly from the same sources as the ITV disc. Nevertheless, the lossless audio included here makes a difference: it’s a big improvement over the lossy track included on the ITV Blu-ray. Also, the behind-the-scenes footage and vintage featurette are interesting for fans of the film. NB. The original pressing of this disc included an encoding error which Network have apparently now corrected. References: Arnold, Gordon B, 2008: Conspiracy Theory in Film, Television, and Politics. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers Baudrillard, Jean, 1995: The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Indiana University Press Benjamin, Marina, 2003: Rocket Dreams: How the Space Age Shaped Our Vision of a World Beyond. London: Simon & Schuster Cobley, Paul, 2002: ‘Justifiable Paranoia: The Politics of Conspiracy in 1970s American Film’. In: Mendik, Xavier (ed), 2002: Shocking Cinema of the 1970s. London: Noir Publishing: 74-87 Cook, David A, 2000: Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970-1979. University of California Press De Monchaux, Nicholas, 2011: Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo. Massachussetts Institute of Technology Prince, Stephen, 2000: ‘Political Film in the Nineties’. In: Dixon, Wheeler Winston (ed), 2000: Film Genre 2000: Critical Essays. State University of New York: 63-76 Visual Comparison with the ITV Blu-ray For the sake of comparison, screengrabs from the new Network Blu-ray are on top; grabs of the older ITV Blu-ray are on bottom.

|

|||||

|