|

|

Bound (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th August 2014). |

|

The Film

Bound (Andy and Larry Wachowski, 1996)  Made after the Wachowskis’ bad experience with Assassins (Richard Donner, 1995) – their script was heavily reworked during production, much to their chagrin – and prior to the phenomenal success of their cyberpunk fantasy The Matrix (1999), Bound (1996) saw the Wachowskis working within the confines of the neo-noir (or ‘noir lite’, as it is sometimes called) subgenre. Neo-noir pictures, films which revisited the concerns of classic films noir of the 1940s and 1950s, had been popular since the 1980s and had often held a strong erotic charge (Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat, 1981, being a notable example). However, in the 1990s neo-noir films increasingly came to overlap with the erotic thriller (for example, John Dahl’s The Last Seduction, 1994, and William Friedkin’s Jade, 1995). However, the resurgence in noir motifs wasn’t limited to cinema. Showtime’s excellent neo-noir series Fallen Angels (1993-5), for example, offered adaptations of the work of authors associated with the era of classic films noir such as Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson, alongside adaptations of the noir-tinged work of more contemporary writers (Walter Mosley, James Ellroy). Photographed in a way that offered a pastiche of the visual conventions of classic films noir (chiaroscuro lighting, obtuse compositions), Fallen Angels upped the ante in terms of sexual content, once again underscoring the association between neo-noir and the erotic thriller. Made after the Wachowskis’ bad experience with Assassins (Richard Donner, 1995) – their script was heavily reworked during production, much to their chagrin – and prior to the phenomenal success of their cyberpunk fantasy The Matrix (1999), Bound (1996) saw the Wachowskis working within the confines of the neo-noir (or ‘noir lite’, as it is sometimes called) subgenre. Neo-noir pictures, films which revisited the concerns of classic films noir of the 1940s and 1950s, had been popular since the 1980s and had often held a strong erotic charge (Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat, 1981, being a notable example). However, in the 1990s neo-noir films increasingly came to overlap with the erotic thriller (for example, John Dahl’s The Last Seduction, 1994, and William Friedkin’s Jade, 1995). However, the resurgence in noir motifs wasn’t limited to cinema. Showtime’s excellent neo-noir series Fallen Angels (1993-5), for example, offered adaptations of the work of authors associated with the era of classic films noir such as Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson, alongside adaptations of the noir-tinged work of more contemporary writers (Walter Mosley, James Ellroy). Photographed in a way that offered a pastiche of the visual conventions of classic films noir (chiaroscuro lighting, obtuse compositions), Fallen Angels upped the ante in terms of sexual content, once again underscoring the association between neo-noir and the erotic thriller.

Jans B Wager notes that neo-noir pictures often revised and reworked ‘sex or gender representations and, like classic noir, focuses on class’ (2009: 10). This is true of Bound, which takes a conventional noir plot (a character, usually defined as working class, is seduced by a femme fatale into collaborating in a robbery or murder) but subverts it by making both lead characters female. The plot recalls James M Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934), itself the subject of several film adaptations, in which a young drifter, Frank Chambers, is seduced by the beautiful Cora into killing Cora’s husband Nick Papadakis. In Bound, ex-con Corky (Gina Gershon), who has just been released from prison having served five years for robbery (‘the redistribution of wealth’, as Corky calls it), is seduced by gangster’s moll Violet (Jennifer Tilly) into stealing a suitcase full of money from Violet’s low-ranking mobster boyfriend/pimp Caesar (Joe Pantoliano). As with many neo-noir pictures produced during the mid-1990s, Bound foregrounded explicit sexuality: the extended, and moderately explicit, sex scene between Gershon and Tilly’s characters, described in an article in gay and lesbian magazine The Advocate as ‘the most extensive lesbian lovemaking ever portrayed in a mainstream film’ (Frutkin, 1995: 56), was trimmed for the film’s original release in the US, and it also formed a key part of the film’s original marketing.  Predicated on the promise of explicit sex between Gershon and Tilly, the film ‘was heavily promoted to both lesbians and straight men’ (Benshoff & Griffin, 2005: 258, emphasis in original). Bound ‘was hyped to the queer community with lesbian bar parties and assorted tie-in gimmicks, but those same steamy promotional girl-on-girl shots were also used in straight men’s magazines’ (ibid.). The film’s use of strong lesbian characters, especially compared with the bumbling male characters in the narrative, may be interpreted as positive, but it has also been seen as exploitative, especially in the ways in which it positions both Corky and Violet ‘on the wrong side of the law’ (for example, see Darren, 2000: 32). The violence directed against the female characters has also been criticised, as has the film’s focus on the ‘killer dyke’ stereotype (Benshoff & Griffin, op cit.: 258; Gemunden et al, 1997: 2). Ultimately, the best way to describe the film is perhaps to use the word ‘divisive’, although over time it has acquired a strong cult following. Predicated on the promise of explicit sex between Gershon and Tilly, the film ‘was heavily promoted to both lesbians and straight men’ (Benshoff & Griffin, 2005: 258, emphasis in original). Bound ‘was hyped to the queer community with lesbian bar parties and assorted tie-in gimmicks, but those same steamy promotional girl-on-girl shots were also used in straight men’s magazines’ (ibid.). The film’s use of strong lesbian characters, especially compared with the bumbling male characters in the narrative, may be interpreted as positive, but it has also been seen as exploitative, especially in the ways in which it positions both Corky and Violet ‘on the wrong side of the law’ (for example, see Darren, 2000: 32). The violence directed against the female characters has also been criticised, as has the film’s focus on the ‘killer dyke’ stereotype (Benshoff & Griffin, op cit.: 258; Gemunden et al, 1997: 2). Ultimately, the best way to describe the film is perhaps to use the word ‘divisive’, although over time it has acquired a strong cult following.

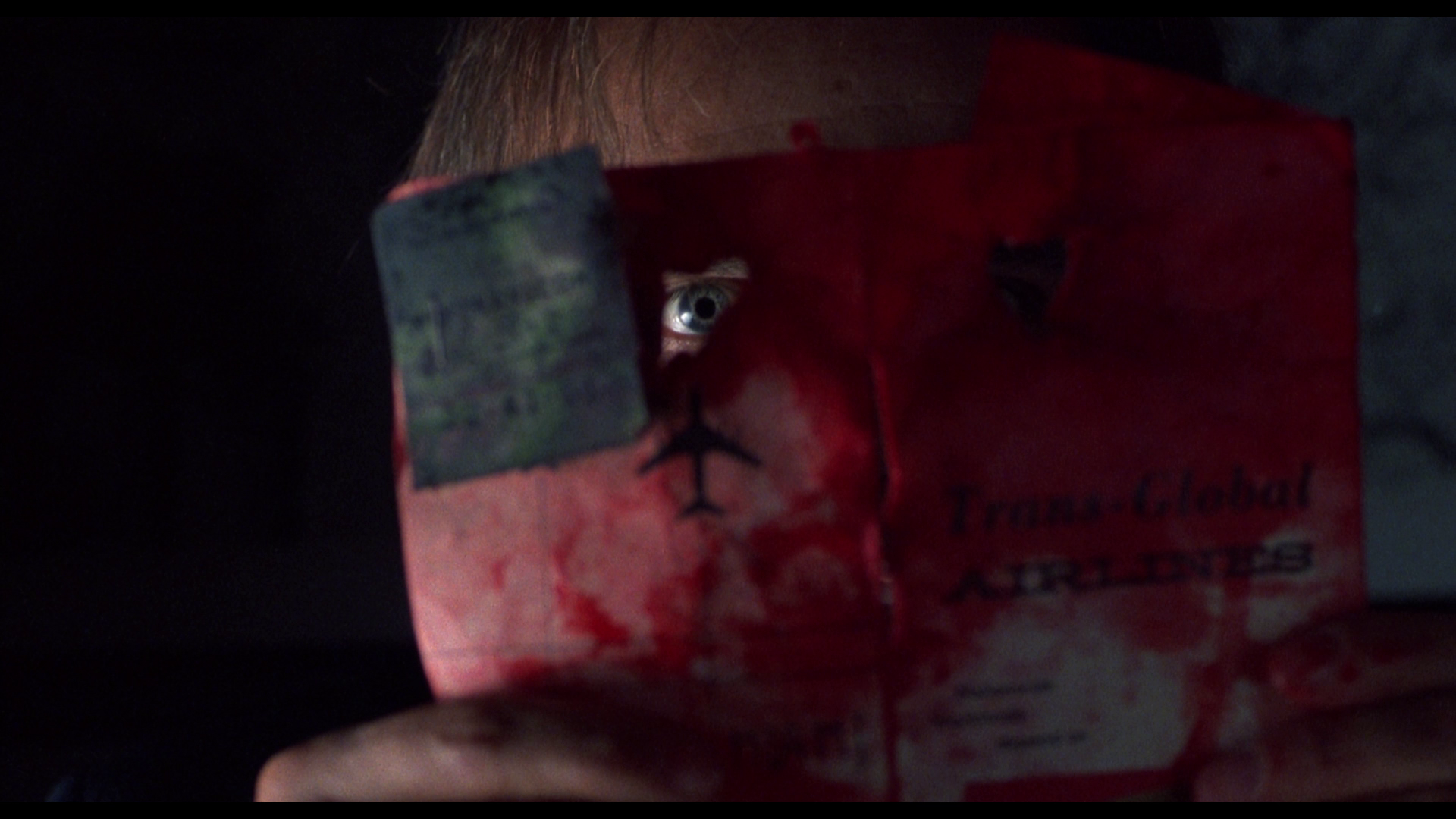

The narrative unfolds in a non-linear manner. The film opens with Corky tied up and dumped in a wardrobe. On the soundtrack, we are presented with fragments of conversations from sequences that appear later in the film, as Corky reflects on the events that led to her current predicament. On taking a job as the handyman in the apartment building in which Violet and Caesar live, Corky soon finds herself seduced by Violet. Renovating and redecorating the apartment next door to the one shared by Violet and Caesar, Corky overhears another man, Shelly (Barry Kivel), being interrogated violently by Johnnie Marzzone (Christopher Meloni). Marzzone bashes Shelly’s head against the toilet basin in Caesar’s bathroom, hoping that Shelly will lead him to the money that Shelly stole from ‘the Business’ (when Corky asks Violet if Caesar is involved with the Mafia, Violet tells her, ‘Honey, nobody really calls it that. Caesar calls it “the Business”’). Caesar resents Johnnie’s sadistic streak, but Caesar is employed by Johnnie’s father Gino Marzzone (Richard C Sarafian). Shortly after, Violet tells Corky that ‘I want out. I want a new life. I see what I’ve been wanting for but I can’t do it alone. I need your help, Corky’. Violet elicits Corky’s help in a plan to steal the money that Johnnie and Caesar have retrieved from Shelly (to ‘fuck over the mob’, as Corky expresses it). Corky and Violet hide the money in the empty apartment next to Caesar’s. However, when Johnnie and his father Gino arrive, instead of running (as Violet predicted he would) Caesar does something unexpected: he kills Johnnie, Gino and Johnnie’s henchmen. Things become even more complicated when a senior member of ‘the Business’, Micky Malnato (John Ryan), arrives and demands to know where the money is. Desperate to cover his own back, Caesar becomes enmeshed in a web of lies. Meanwhile, he becomes increasingly suspicious of both Violet and Corky.  Chris Straayer has highlighted the lean efficiency of Bound’s opening sequence. The titles sequence, with its ‘stark lights and deep shadows’, as the roving camera rotates around the film’s title, moving from a position of ‘extreme close-up obscurity to distanced readability (of the film’s title)’ hints at the noir-ish concerns of the film’s narrative (2012: 219). This is followed by a prowling camera that roves through the contents of a wardrobe, outlining them in extreme close-up, in the process ‘enlarging and distorting’ a light fitting ‘to vulgar proportions and thus creating […] a bulbous projection that suggests a sex toy as much as a ceiling light’ (ibid.). As the camera wanders through the wardrobe, making it seem much larger than it is, it reveals feminine objects that are fetishised in lovingly-shot close-up (‘hat boxes, evening dresses, and high heels’) (ibid.). Finally, the camera dollies alongside the body of Corky, bound with rope and left on the floor of the wardrobe, glimpsing first her heavy masculine work boots, ‘past work pants, ribbed undershirt, and biceps displaying’ her labrys tattoo (ibid.). On the soundtrack, we hear snatches of conversations that take place later in the film’s narrative. A cut to an elevator follows, as Corky enters it alongside Violet and Caesar. An overhead shot of the trio offers foreshadowing of the love triangle that will develop as the narrative progresses, ‘graphically articulat[ing] sexual triangulation’ (ibid.). Both Corky and Violet ‘wear black leather jackets despite the butch-femme contrast’ between them (ibid.). Caesar and Violet leave the elevator, Caesar in front and Violet following him; as they walk away from the camera, it gazes at Violet from Corky’s point-of-view, focusing on Tilly’s shapely legs. Caesar unlocks the door to their rooms, ‘never acknowledging the femme [Violet] who accompanies him’ and thus ‘implications of prostitution arise’ (ibid.). Meanwhile, Corky enters the apartment next door, and it is made clear to us that she is the building’s janitor/handyman. Chris Straayer has highlighted the lean efficiency of Bound’s opening sequence. The titles sequence, with its ‘stark lights and deep shadows’, as the roving camera rotates around the film’s title, moving from a position of ‘extreme close-up obscurity to distanced readability (of the film’s title)’ hints at the noir-ish concerns of the film’s narrative (2012: 219). This is followed by a prowling camera that roves through the contents of a wardrobe, outlining them in extreme close-up, in the process ‘enlarging and distorting’ a light fitting ‘to vulgar proportions and thus creating […] a bulbous projection that suggests a sex toy as much as a ceiling light’ (ibid.). As the camera wanders through the wardrobe, making it seem much larger than it is, it reveals feminine objects that are fetishised in lovingly-shot close-up (‘hat boxes, evening dresses, and high heels’) (ibid.). Finally, the camera dollies alongside the body of Corky, bound with rope and left on the floor of the wardrobe, glimpsing first her heavy masculine work boots, ‘past work pants, ribbed undershirt, and biceps displaying’ her labrys tattoo (ibid.). On the soundtrack, we hear snatches of conversations that take place later in the film’s narrative. A cut to an elevator follows, as Corky enters it alongside Violet and Caesar. An overhead shot of the trio offers foreshadowing of the love triangle that will develop as the narrative progresses, ‘graphically articulat[ing] sexual triangulation’ (ibid.). Both Corky and Violet ‘wear black leather jackets despite the butch-femme contrast’ between them (ibid.). Caesar and Violet leave the elevator, Caesar in front and Violet following him; as they walk away from the camera, it gazes at Violet from Corky’s point-of-view, focusing on Tilly’s shapely legs. Caesar unlocks the door to their rooms, ‘never acknowledging the femme [Violet] who accompanies him’ and thus ‘implications of prostitution arise’ (ibid.). Meanwhile, Corky enters the apartment next door, and it is made clear to us that she is the building’s janitor/handyman.

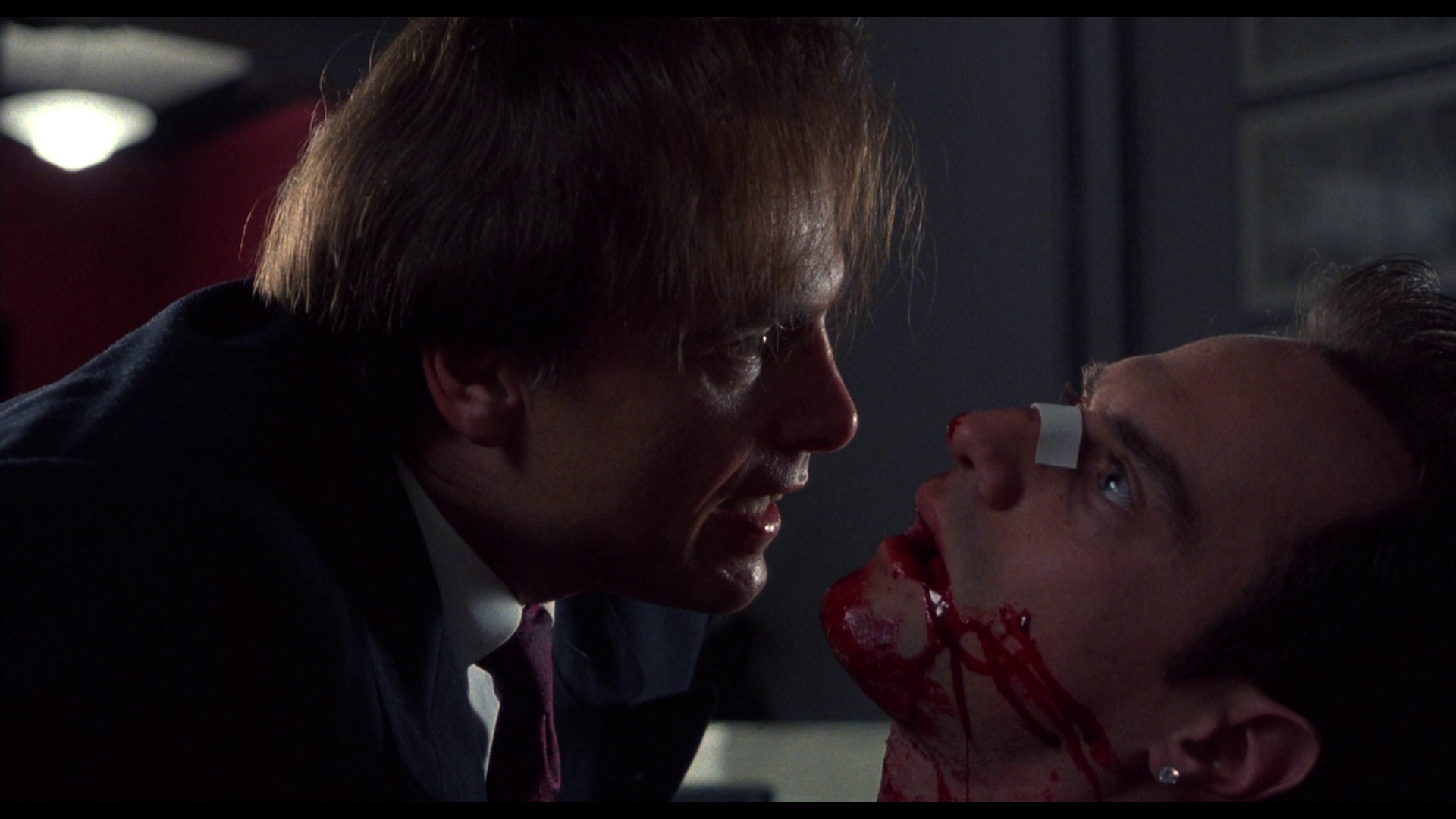

Linda Ruth Williams suggests that many erotic thrillers and neo-noir pictures of the 1990s are as much about ‘desire-fuelled male failure’ as they are about femmes fatales (2005: 109). In the films, ‘feminisation [of the male lead] is an effect of both the sexual glamourisation the fall-guy undergoes and his systematic disempowerment’ (ibid.: 110). Williams quotes Larry Wachowski, who asserted that the ‘fall guy’ in a neo-noir picture is usually ‘the most hysterical character – the most “feminine”’ (quoted in ibid.). Whilst Caesar isn’t depicted as sexually glamourous (although he displays a similar amount of skin to Gershon and Tilly, appearing nude – his modesty covered by a towel – after a shower), he is clearly seen (by Micky, for example) as henpecked. When Micky arrives in Caesar’s apartment, he notices that Caesar has moved the furniture around. Although he has done this to hide the bloodstains from where the bodies of Johnnie, Gino and the other goons fell, Caesar tells Micky he has done this because Violet told him to. ‘You know women, Mick’, Ceasar says. ‘Sure, Caes. They make you do stupid things, don’t they’, Micky comments knowingly. Caesar’s behaviour also becomes increasingly hysterical (and therefore more stereotypically ‘feminine’) as the narrative progresses. From the outset, he is presented as something of a buffoon. When he interrupts Violet’s attempt to seduce Corky, at first he is angry when he sees his wife sitting alone in the dark with a mannish figure wearing work boots and workmen’s clothing. However, when he realises that Corky is a woman, he reinterprets the situation as completely innocent (‘I thought…’, he begins, embarrassed, before quipping, ‘Fucking dark in here!’), refusing to consider the possibility that Violet is having a sexual liaison with another woman. Later, when he becomes aware that Violet has betrayed him, he shouts at her, and reinforces the extent to which his worldview associates a person’s worth with their wealth: ‘Ungrateful fucking bitch. Vi, you were nothing before you met me. Don’t you remember, you had nothing? Who gave you this place, eh? Who gave it to you? I did, Vi. I did’. The rant is topped off by the materialistic parallelism, ‘You were nothing; you had nothing’.  The men within the film are also deeply sadistic. Johnnie is the most outwardly brutal: in the scene in which he is introduced, he is pounding Shelly’s head against the toilet basin in Caesar’s apartment. Caesar disapproves of Johnnie’s violent streak. However, when Caesar is provoked, he too becomes increasingly sadistic, both towards his associated in ‘the Business’ and towards Corky and Violet. When he realises that Corky is a lesbian and has been conspiring with Violet against him, Caesar lashes out: ‘I shoulda seen this coming the minute I met you’, he rants, ‘Everyone knows your kind can’t be trusted. Fucking queers, you make me sick’. As Corky notes at one point, ‘These people are worse than the cops because they have lots of money and no rules. You fuck them, you’d better do it right’. The men within the film are also deeply sadistic. Johnnie is the most outwardly brutal: in the scene in which he is introduced, he is pounding Shelly’s head against the toilet basin in Caesar’s apartment. Caesar disapproves of Johnnie’s violent streak. However, when Caesar is provoked, he too becomes increasingly sadistic, both towards his associated in ‘the Business’ and towards Corky and Violet. When he realises that Corky is a lesbian and has been conspiring with Violet against him, Caesar lashes out: ‘I shoulda seen this coming the minute I met you’, he rants, ‘Everyone knows your kind can’t be trusted. Fucking queers, you make me sick’. As Corky notes at one point, ‘These people are worse than the cops because they have lots of money and no rules. You fuck them, you’d better do it right’.

The film arguably ‘works’ because of its subversive switching of genders. A traditional noir picture would give the role that Corky plays in the narrative to a male character, who would be duped into taking part in the plot against Caesar by the femme fatale, Violet. Invariably, as the narrative progresses this male character would come to realise that he himself has been trapped by the femme fatale character. However, at the end of Bound, Corky and Violet drive off together, apparently very much in love. As Chris Straayer has argued, ‘[t]hrough its narrative, Bound suggests that in contrast to the heterosexual failings of classic film noir, women can trust one another’ (quoted in Williams, 2005: 368). In the interview with Gershon included on this Blu-ray, the actress notes that for her, the relationship between Corky and Violet ‘was all about trust’, rather than the fact that these two characters were lesbians. At one point, Corky explains the important of trust amongst thieves to Corky: ‘For me, stealing has always been a lot like sex. Two people want the same thing, they get in a room, they talk about it. They start to plan. It’s kind of like flirting; it’s kind of like foreplay. Of course, the more they talk about it, the wetter they get. The only difference is, I can fuck someone I’ve just met; but to steal, I need to know someone like I know myself’.  Gershon appeared in the film having already played a bisexual character in Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls (1995), and in her interview on this disc she states that her agent tried to persuade her not to take the role of Corky for fear of Gershon being locking into playing lesbians. Subsequently, Gershon would appear in the Jim Thompson adaptation This World, Then the Fireworks (Michael Oblowitz, 1997) as a woman involved in an incestuous relationship with her brother, played by Billy Zane. Speaking at the time of the release of This World, Then the Fireworks, Gershon would refer to these three films as her ‘trilogy of perversion’ (quoted in Williams, op cit.: 196). In the sweaty, claustrophobic setting (the film rarely ventures out of the two apartments: Violet and Caesar’s apartment; and the apartment next door to it, which Corky is decorating) and its focus on a sexuality that has become weaponised, and relationships that are a veiled form of exploitation, Bound has much in common with the work of Jim Thompson. Gershon appeared in the film having already played a bisexual character in Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls (1995), and in her interview on this disc she states that her agent tried to persuade her not to take the role of Corky for fear of Gershon being locking into playing lesbians. Subsequently, Gershon would appear in the Jim Thompson adaptation This World, Then the Fireworks (Michael Oblowitz, 1997) as a woman involved in an incestuous relationship with her brother, played by Billy Zane. Speaking at the time of the release of This World, Then the Fireworks, Gershon would refer to these three films as her ‘trilogy of perversion’ (quoted in Williams, op cit.: 196). In the sweaty, claustrophobic setting (the film rarely ventures out of the two apartments: Violet and Caesar’s apartment; and the apartment next door to it, which Corky is decorating) and its focus on a sexuality that has become weaponised, and relationships that are a veiled form of exploitation, Bound has much in common with the work of Jim Thompson.

Partly thanks to these roles, Gershon became something of an icon amongst the lesbian community, her screen persona ‘defined through her negotiation […] of a sexual/subjective ambivalence which has maximized her appeal to both genders’ (Williams, op cit.: 197). In between the more famous ‘trilogy of perversion’, Gershon took smaller, less high profile roles in a number of other thrillers: the oddball straight-to-video thiller Flinch (1994), about two ‘living mannequins’ who witness a murder; Volker Schlondorff’s neo-noir adaptation of James Hadley Chase’s novel Palmetto (1998); and the cop-based thriller Black and White (Marcell Ivanyi, 1994). Gershon’s bravery in ‘bucking good box office sense in embracing gay roles’ ensured her popularity amongst lesbian audiences, although in reality this is based solely on a small handful of performances: as the bisexual Cristal Connors in Showgirls, her role as Corky in Bound and her casting as Jacki in Prey for Rock & Roll (Alex Steyermark, 2003), together with her appearance in the famous ‘coming out’ episode of the sitcom Ellen (ABC, 1994-8), broadcast in April 1997 under the title ‘The Puppy Episode’, in which Ellen (Ellen Degeneres) invites her friends to her apartment, so that she may ‘come out’ to them. Gershon, along with k.d. lang, played one of the objects of Ellen’s repressed desire in a fantasy sequence within the episode. Gershon was attracted to playing Corky because she considered the part ‘like those Marlon Brando roles’ (quoted in Frutkin, op cit.: 56). Sex-positive feminist Susie Bright, attached to the film as a technical consultant, claimed during the production that Gershon’s attempt to play the role of Corky as if she were ‘Jimmy Dean and Brando’ was ‘the kind of juice you want—the romantic dream of lesbian masculinity is based on movie-star feelings like that’ (quoted in ibid.). Despite being present during production (and appearing on screen as an extra) to offer ‘a Good Housekeeping seal of approval—as if I’m vouching for really good lesbian sex’, Bright was not allowed on the closed set during the shooting of the sex scene between Corky and Violet (quoted in ibid.: 57). However, Bright advised the Wachowskis to avoid the usual depiction of lesbian cunnilingus, telling the directors that the ‘butch-femme couple’ with the ‘stormy, suspenseful relationship’ needed to be depicted in a sex scene that involved ‘penetration. You want to imply that they’re fucking, and that’s crucial to understanding their relationship’ (quoted in ibid.). Bright informed the Wachowskis that their original script, which shied away from a clear depiction of Violet and Corky’s lesbian sexuality, was too tame, and ‘on behalf of all the lesbians who have been disappointed by one shitty sex scene after another, could I please be their lesbian sex consultant’ (Bright, quoted in Bono, 1996: 65).  Barbara Mennel has claimed that Bound elevated ‘signifiers of lesbian identity into the mainstream’ (Mennel, 2013: 97). Both women are clad throughout the film in black leather (the creaking of leather is a key part of the sound design during the sequence in which Violet seduces Corky), and Corky is associated with the men’s underwear which she wears and her red, beaten-up ’63 Chevy pick-up truck (at the end of the film, having stolen Caesar’s money, Corky replaces this with a shiny new, equally red, pick-up). The double-headed axe tattoo, the labrys, on Corky’s right shoulder is a signifier of her lesbian identity: Violet recognises it immediately, the icon having been appropriated since the 1970s as a symbol of female strength. Within the film, this iconography, Mellen argues, ‘move[s] from subcultural signs to becoming fashion statements’ (ibid.). Barbara Mennel has claimed that Bound elevated ‘signifiers of lesbian identity into the mainstream’ (Mennel, 2013: 97). Both women are clad throughout the film in black leather (the creaking of leather is a key part of the sound design during the sequence in which Violet seduces Corky), and Corky is associated with the men’s underwear which she wears and her red, beaten-up ’63 Chevy pick-up truck (at the end of the film, having stolen Caesar’s money, Corky replaces this with a shiny new, equally red, pick-up). The double-headed axe tattoo, the labrys, on Corky’s right shoulder is a signifier of her lesbian identity: Violet recognises it immediately, the icon having been appropriated since the 1970s as a symbol of female strength. Within the film, this iconography, Mellen argues, ‘move[s] from subcultural signs to becoming fashion statements’ (ibid.).

To some extent, the film is about the performative aspects of sexuality: Gershon’s butch demeanour as Corky is placed in juxtaposition with Tilly’s performance as the ‘sexpot’ Violet. Violet, of course, poses as a straight woman: she is Caesar’s moll, and she also masquerades as a call girl. When Corky overhears Violet having sex with another man in Caesar’s apartment, Corky confronts Violet. ‘What you heard wasn’t sex’, Violet asserts. ‘What was it then?’, Corky asks. ‘Work’, Violet tells her. For Violet, her heterosexual identity is her ‘work’; her lesbian identity is her core self. There is no question of her being bisexual (San Fillippo, 2013: 36). In one scene, Violet tells Corky, ‘I know what I am. I don’t have to have it tattooed on my shoulder’. Violet is able to walk in both straight and gay society: Corky and Violet’s ‘sleight-of-hand [in terms of their plot to steal the money] is predicated on Violet slipping from the appearance of heterosexuality into the practice of lesbianism, and forging criminal alliances in the process, without her man suspecting’ (Williams, op cit.: 199). Caesar’s failure to recognise or acknowledge Violet’s lesbianism (and her deception of him, both sexually and in terms of her plot to steal the money) allows Violet and Corky’s plot to succeed. The film places Corky and Violet in juxtaposition, with Corky as the ‘butch’ lesbian and Violet as the ‘femme’. Violet is ‘behaviorally bisexual’ but she considers her heterosexual activities to be ‘work’ – a product of ‘financial incentive and, given Caesar’s mob ties, self-preservation’ – and tells Corky ‘I know what I am’ (San Fillippo, 2013: 36). However, Violet is seduced by Corky’s physicality. ‘I am so in awe of people who can fix things’, Violet tells Corky early in the film, ‘My dad was like that. We never had anything new. Whenever anything was broken, he would just open it up, tinker with it a little bit, fix it’. Tilly’s line delivery invests this ostensibly innocent line of dialogue with remarkable sensuality; Violet’s mentioning of her father during her celebration of Corky’s physicality offers a suggestion of sexual abuse in Violet’s past.  Corky is outwardly lesbian (‘I’m just here to get laid’, she asserts during her visit to a lesbian bar). Her mannish clothing and tattoos are contrasted with Violet’s figure-hugging dresses, omnipresent make-up and Tilly’s breathy line delivery. She expresses a masculine worldview too: when Violet pisses her off during one scene, Corky asserts, ‘If there’s one thing I can’t stand about sleeping with women, it’s all the fucking mind reading’. When Corky is called to Violet’s apartment to retrieve Violet’s earring, which she has dropped down the sink, Corky’s mastery of plumbing is watched closely by Violet, who stands behind her, her crotch at the height of Corky’s head. Slow-motion close-ups of Corky’s hands as she disengages the pipework under the sink, water spilling over them, offer an obvious metaphor for sex. However, it is Violet who seduces Corky. ‘What are you doing?’, Corky asks during the seduction scene, bemused. ‘Isn’t it obvious? I’m trying to seduce you’, Violet offers, spelling it out. ‘Why?’, Corky asks. ‘Because I want to’, Violet tells her. In the extended sex scene that is integral to the film’s depiction of their relationship, Violet takes the active role, penetrating Corky with her fingers whilst cradling her in her arms. The plan to steal the money is also Violet’s. Where Corky displays her sexuality via her ‘louche swagger’ (Darren, op cit.: 32), her tattoos and her masculine dress code, Violet’s lesbian identity is concealed but no less secure, hidden but not passive or submissive. Corky is outwardly lesbian (‘I’m just here to get laid’, she asserts during her visit to a lesbian bar). Her mannish clothing and tattoos are contrasted with Violet’s figure-hugging dresses, omnipresent make-up and Tilly’s breathy line delivery. She expresses a masculine worldview too: when Violet pisses her off during one scene, Corky asserts, ‘If there’s one thing I can’t stand about sleeping with women, it’s all the fucking mind reading’. When Corky is called to Violet’s apartment to retrieve Violet’s earring, which she has dropped down the sink, Corky’s mastery of plumbing is watched closely by Violet, who stands behind her, her crotch at the height of Corky’s head. Slow-motion close-ups of Corky’s hands as she disengages the pipework under the sink, water spilling over them, offer an obvious metaphor for sex. However, it is Violet who seduces Corky. ‘What are you doing?’, Corky asks during the seduction scene, bemused. ‘Isn’t it obvious? I’m trying to seduce you’, Violet offers, spelling it out. ‘Why?’, Corky asks. ‘Because I want to’, Violet tells her. In the extended sex scene that is integral to the film’s depiction of their relationship, Violet takes the active role, penetrating Corky with her fingers whilst cradling her in her arms. The plan to steal the money is also Violet’s. Where Corky displays her sexuality via her ‘louche swagger’ (Darren, op cit.: 32), her tattoos and her masculine dress code, Violet’s lesbian identity is concealed but no less secure, hidden but not passive or submissive.

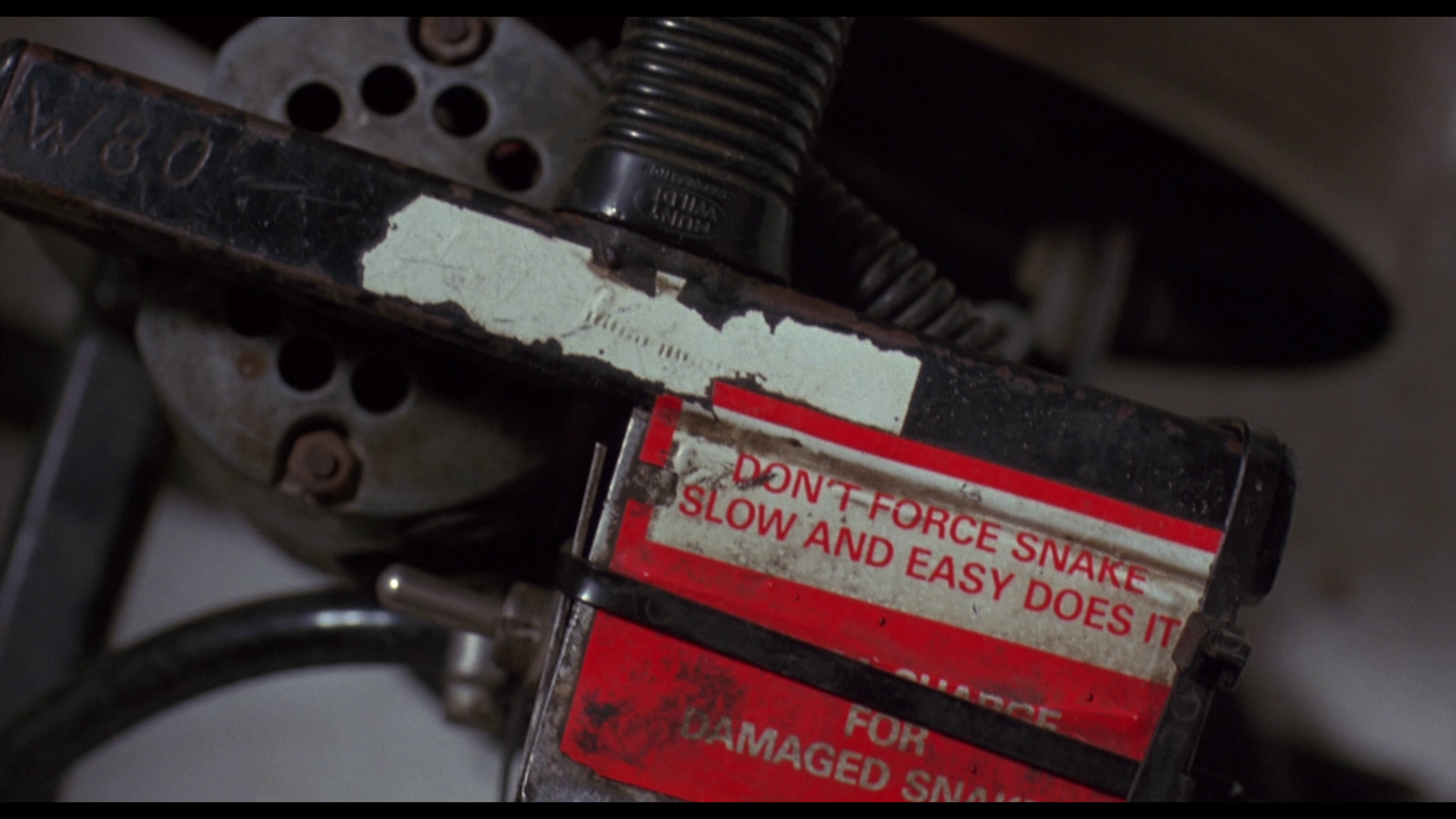

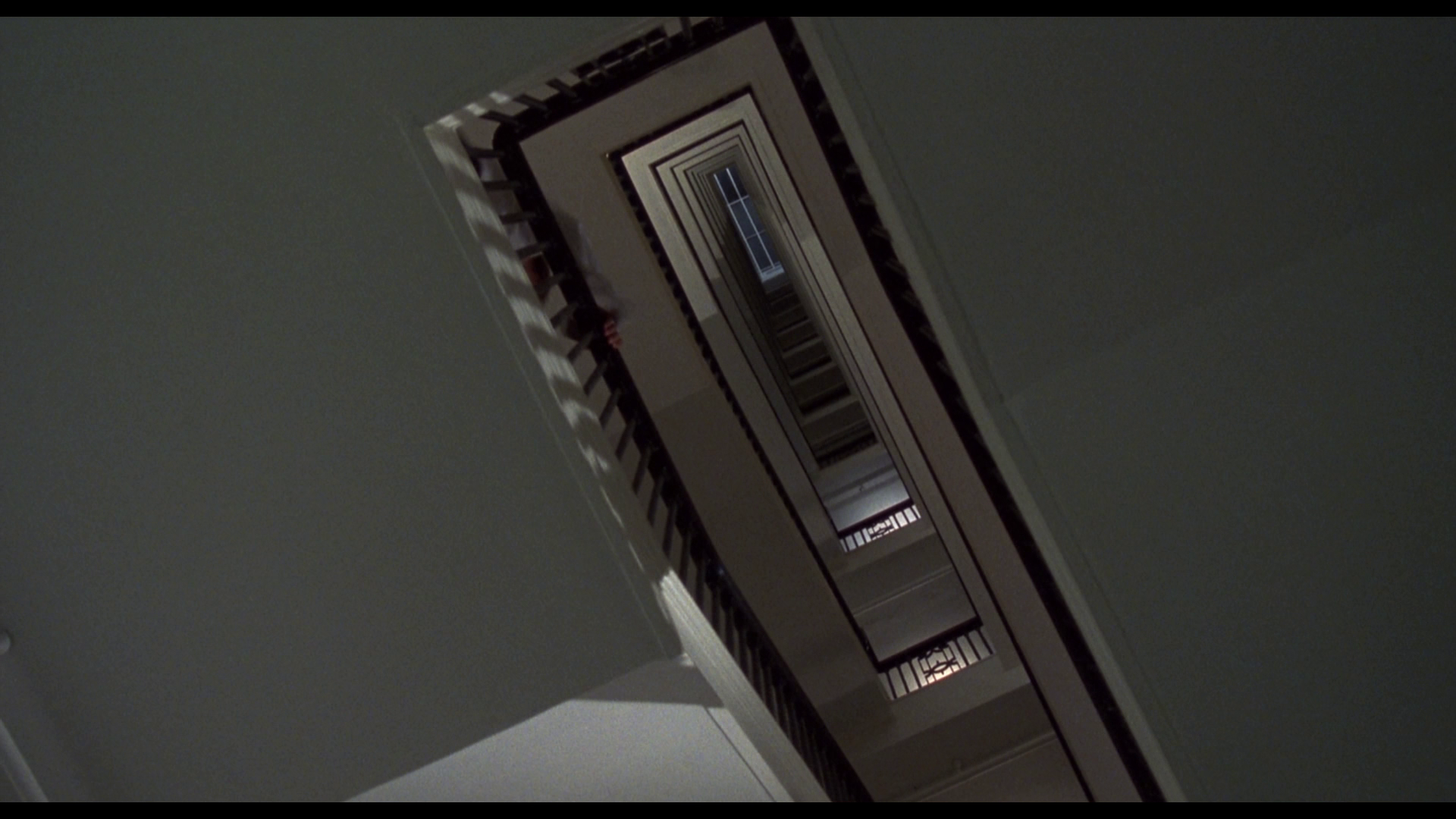

The film has a claustrophobic setting, rarely venturing outside of the two apartments: Violet and Caesar’s apartment, and the apartment next door that Corky is redecorating. Shortly after beginning her work, through the paper thin walls that separate the two apartments Corky overhears Caesar and Violet having sex. An ironic cut follows, as the butch Corky shoves the phallic hose of a motorised drain snake into the plughole of the bathtub and the camera slowly moves along the length of the contraption to reveal a label that declares, ‘DON’T FORCE SNAKE. SLOW AND EASY DOES IT’. The scene offers an ironic commentary on heterosexual sex, and it also serves to reinforce Corky’s desire for Violet. Shortly after, as if indicating that she is aware Corky overheard her tryst with Caesar, Violet informs Corky that ‘The walls here are so terribly thin, as if you are in the same room’.  The other characters (Johnnie, Gino, Micky, Shelly) wander (or are dragged) into Violet and Caesar’s apartment. Only a handful of sequences take place outside the apartment building: Corky’s visit to a lesbian bar, and a couple of short scenes in the street outside the apartment building itself. Corky and Violet’s apartment is riddled with allusions to other films: its ‘reference points are purely cinematic’ (Wallace, 2009: 81). Where most crime movies make use of and explore the landscape of the city, Bound focuses on interiors, and ‘even the architectural fixtures seem to derive chiefly from other films about sexual dissimulation and the spatial paranoia aroused in its vicinity’ (ibid.). When Johnnie and his crew interrogate Shelly about the money, Johnnie bashes Shelly’s head against the toilet basin. Working in the apartment next door, Corky overhears this, at first confused as to what is happening, but as she becomes increasingly aware of what is taking place in Violet and Caesar’s apartment, we are presented with an overhead shot of the toilet bowl as it fills with blood – a visual reference to Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), in which as the conspiracy tightens around him Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) visualises a toilet bowl overflowing with blood. When Violet flees from the apartment, Caesar chases after her, following her down the staircase of the apartment building. A low-angle shot of the staircase, framing it with precise symmetry, recalls the shots of the staircase in the bell tower in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Caesar’s plan to hide the bodies of Johnnie and his crew in the bathtub, behind the shower curtain, and his use of the shower as a form of distraction from this when Micky arrives at the apartment, bring to mind Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). In all three of the films that Bound alludes to, hotels/motels form the locus for sexual betrayal, ‘substituting spying and surveillance for privacy’ (ibid.). In beginning with the bound Corky concealed in the wardrobe, and later focusing on Caesar’s attempts to hide the bodies of Johnnie and his cronies whilst he entertains Micky, the film also offers an oblique allusion to Hitchcock’s Rope (1948). The other characters (Johnnie, Gino, Micky, Shelly) wander (or are dragged) into Violet and Caesar’s apartment. Only a handful of sequences take place outside the apartment building: Corky’s visit to a lesbian bar, and a couple of short scenes in the street outside the apartment building itself. Corky and Violet’s apartment is riddled with allusions to other films: its ‘reference points are purely cinematic’ (Wallace, 2009: 81). Where most crime movies make use of and explore the landscape of the city, Bound focuses on interiors, and ‘even the architectural fixtures seem to derive chiefly from other films about sexual dissimulation and the spatial paranoia aroused in its vicinity’ (ibid.). When Johnnie and his crew interrogate Shelly about the money, Johnnie bashes Shelly’s head against the toilet basin. Working in the apartment next door, Corky overhears this, at first confused as to what is happening, but as she becomes increasingly aware of what is taking place in Violet and Caesar’s apartment, we are presented with an overhead shot of the toilet bowl as it fills with blood – a visual reference to Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), in which as the conspiracy tightens around him Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) visualises a toilet bowl overflowing with blood. When Violet flees from the apartment, Caesar chases after her, following her down the staircase of the apartment building. A low-angle shot of the staircase, framing it with precise symmetry, recalls the shots of the staircase in the bell tower in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Caesar’s plan to hide the bodies of Johnnie and his crew in the bathtub, behind the shower curtain, and his use of the shower as a form of distraction from this when Micky arrives at the apartment, bring to mind Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). In all three of the films that Bound alludes to, hotels/motels form the locus for sexual betrayal, ‘substituting spying and surveillance for privacy’ (ibid.). In beginning with the bound Corky concealed in the wardrobe, and later focusing on Caesar’s attempts to hide the bodies of Johnnie and his cronies whilst he entertains Micky, the film also offers an oblique allusion to Hitchcock’s Rope (1948).

This is the unrated version of the film (the US ‘R’ rated version trimmed the sex scene between Corky and Violet slightly, and also removed one of the blows to Shelly’s head as Johnnie holds him over the toilet basin) and runs for 108:33 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 32Gb of space on a dual-layer Blu-ray, this presentation of Bound is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. (By comparison, the Blu-ray released by Olive in the US is in 1.78:1 and contains a sliver more information at the top and bottom of the frame.) The presentation on Arrow’s disc uses the AVC codec. Taking up approximately 32Gb of space on a dual-layer Blu-ray, this presentation of Bound is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. (By comparison, the Blu-ray released by Olive in the US is in 1.78:1 and contains a sliver more information at the top and bottom of the frame.) The presentation on Arrow’s disc uses the AVC codec.

The disc is a huge improvement over the DVDs that have been available. Contrast levels are stronger, allowing the noir-esque aesthetic to shine. Blacks are deeper, and there is far more detail within the image. Although much of the film takes place in the apartments, lit low, there is a lot of deep focus photography, and the photography in this presentation has a great sense of depth to it. A natural grain structure is present throughout the film too. The Arrow Blu-ray has more natural skin tones than the Olive Blu-ray released in the US (which also contains a noticeably brighter presentation of the film), and it seems closer in spirit to the Blu-ray released in France. (Both the Arrow and French Blu-rays lose a sliver of information on both the left and right hand sides of the frame, in comparison with the Olive disc.) A visual comparison of Arrow's Blu-ray with the DVD transfer is contained at the bottom of this page.

Audio

There are two audio options, both lossless: a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix and a LPCM 2.0 stereo channel. Both are clean and clear, though the LPCM 2.0 stereo mix seems to have more depth and weight to it. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

Audio commentary with writer-directors Andy and Larry Wachowski, editor Zach Staenberg and Susie Bright This is the same lively, information-pack audio commentary that was included on the film’s DVD releases. ‘Modern Noir: The Sights and Sounds of Bound’ (29:24) In this featurette, Director of Photography Bill Pope, editor Zach Staenberg and composer Don Davis are interviewed separately. Pope reveals that he was hired after another cinematographer, ‘a big name cinematographer’, turned up and realised how low the film’s budget was and quit. Pope was hired based on his work on Raimi’s Army of Darkness (1993). He asserts that the casting of Jennifer Tilly allowed producers to raise a little more money; and the Wachowskis’ work as house painters inspired the script for the film. Pope decided to shoot the picture in ‘almost black and white […] an homage to 50s movies’ in terms of the use of shadow and light. He also talks about the compositions within the film, stating that he tried to ‘box’ the characters in within the frame as a means of signifying their entrapment, ‘by their sexual orientation, by the Mob’. Don Davis talks about the Wachowskis’ work as a team, stating that in order to work on the picture, he ‘needed to learn Wachowski-speak’. Davis thought the film demanded a minimalist score, and the finished score, he says, ‘was kind of a homage to an Ennio Morricone-type approach [….] kind of melodic but still kind of menacing’. For Davis, the film worked because the misogynistic culture of the Mafioso types in the film leads the men to find it impossible to believe that Corky and Violet would be involved with each other. Zach Staenberg discusses how impressed he was with the script and talks about the film’s budget. ‘In this movie, almost every shot is a fresh angle’, Staenberg tells us, which is ‘a tribute to how carefully they [the Wachowskis] had planned and knew what they wanted to see’. The Wachowskis drove to work together and left together, Staenberg tells us; they even ‘completed each other’s sentences’. Their work on then film was carefully-planned, but they were also flexible: Staenberg made some suggestions which were incorporated into then finished film, including his suggestion that prior to the ‘reveal’ of Corky bound within the wardrobe, the film needed a titles sequence. Staenberg also reveals that De Laurentiis wanted the Wachowskis to prune the scene in which Caesar tortures Shelly by cutting off his fingers – but, as Staenberg suggests, this scene was necessary to highlight the sadistic streak within these male characters. Cast Interviews Gina Gerson & Jennifer Tilly – Femme Fatales (26:51) Gershon and Tilly, interviewed separately, discuss their involvement in the film. Gershon says she was advised by her agent not to take the role in the film because she had already played a bisexual character. At one point, Gersion was going to play Violet. Preparing for her role, Gershon watched a lot of films starring Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando. To Gershon, the relationship between Corky and Violet ‘was all about trust’ rather than the fact that the two characters were lesbians. Like Tilly, Gershon suggests that the film wasn’t marketed properly and found its proper audience on home video. Tilly says that during the pitch, De Laurentiis asked the Wachowski’s, ‘Corky, she’s a girl? [….] And Violet, she’s also a girl? [….] I love it: I’ll give you three million dollars’. Tilly claims that at one point, Linda Hamilton was attached to play Violet and Tilly was going to play Corky. Then Hamilton left the project and Rosanna Arquette was cast in the role of Violet. When Arquette became unavailable, Tilly was given the role of Violet; something which Tilly was initially resistant towards, having been somewhat typecast in her previous films as ‘sexpots’. Tilly was persuaded to take the role of Violet when Gershon was cast as Corky. Tilly discusses the logistics of shooting the sex scene with Gershon: it was shot in one take to prevent overseas distributors cutting more explicit material into this sequence. Tilly also talks about working with Pantoliano, who dropped his towel during one take of the scene in which he appears after taking a shower, much to the ire of the Wachowskis. De Laurentiis described Pantoliano as ‘a character actor. He is no leading man’, according to Tilly. The film was marketed to ‘18 year old boys’ but despite a limited release (‘they didn’t really know what they had’) Bound ‘became a cult classic’. Tilly pooh-poohs the talk of a sequel: ‘that moment has passed’, and the time for a sequel would have been within ‘four or five years’ of the release of the original film. Joe Pantoliano – Hail Caesar (13:29) Pantoliano repeats Tilly’s anecdote about De Laurentiis describing Pantoliana as ‘a character actor, not a leading man’. Pantoliano discusses his work with Warner Bros on Risky Business, The Goonies and The Fugitive. Pantoliano was approached about the Caesar role by his friend Marcia Gay Harden, who was originally cast in Bound. Pantoliano watched The Treasure of the Sierra Madre repeatedly, to prepare himself for the paranoia within the character of Caesar. He says the character on the page was ‘clueless’ and in his performance, Pantoliano wanted to make Caesar ‘a worthy adversary’ to Violet and Corky. Christopher Meloni – Here’s Johnny! (10:02) Meloni discusses his character Johnnie, who he says ‘had very poor impulse control, which is why he was such a dangerous and kind of fucked up element to the movie. Everyone has control except for Johnnie’. Meloni decided to make Johnnie ‘unintentionally funny’ because he’d met a lot of men who presented themselves as ‘tough guys [but who] were rather buffoonish, to me’. He says the Wachowskis’ success lay in blending a comic book aesthetic with some of the techniques of Hong Kong cinema. Vintage featurettes: - US featurette (4:53) - International featurette (5:08) These two contemporary production featurettes are promotional pieces and are very similar to one another. They will be familiar to anyone who remembers the film’s original release or has watched one of the numerous DVD releases. They are edited slightly differently, but either way they offer far less depth than the modern interviews included on the disc. Trailers (6:47) TV spots (0:50) Stills gallery (0:28)

Overall

Bound was divisive on its initial release and remains so now, although divorced from its immediate context (and the suggestion that the Wachowskis were attempting to ape the likes of Joel & Ethan Coen and Quentin Tarantino), time has been kind to the film’s vertiginous plotting and visual inventiveness. The interior, claustrophobic nature of the film is one of its great strengths, and the performances (especially Pantoliano’s, which if the comments in his second memoir are to be believed, was largely improvised) are uniformly interesting (see Pantoliano, 2013: 171). The presentation of the film on this release from Arrow is excellent, though it differs from the Olive Blu-ray released in the States and is closer in spirit to the French Blu-ray. The new Arrow Blu-ray also includes an impressive range of contextual material. This release offers a great chance to revisit this slice of 1990s neo-noir and comes with a very strong recommendation. References: Benshoff, Harry M & Griffin, Sean, 2005: Queer Images: A History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Bono, Chastity, 1996: ‘Boundless’. The Advocate (12 November, 1996): 65-7 Darren, Alison, 2000: Lesbian Film Guide. London: Cassell Frutkin, Alan, 1995: ‘Cinema: Bonnie and Bonnie’. The Advocate (5 September, 1995): 55-7 Gemunden, Gerd et al, 1997: ‘From Taboo Parlor to Porn and Passing: An Interview with Monika Treut’. Film Quarterly (50:3, Spring 1997): 2-12 Mennel, Barbara, 2013: Queer Cinema: Schoolgirls, Vampires, and Gay Cowboys. Columbia University Press Pantoliano, Joe, 2013: Asylum: Hollywood Tales from My Great Depression: Brain Dis-Ease, Recovery, and Being My Mother’s Son. New York: Weinstein Books San Fillippo, Maria, 2013: The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television. Indiana University Press Straayer, Chris, 2012: ‘Femme Fatale or Lesbian Femme: Bound in Sexual Differance’. In: Gledhill, Christine (ed), 2012: Gender Meets Genre in Postwar Cinemas. University of Illinois Press:219-32 Wager, Jans B, 2009: Dames in the Driver’s Seat: Rereading Film Noir. University of Texas Press Wallace, Lee, 2011: Lesbianism, Cinema, Space: The Sexual Life of Apartments. London: Routledge Williams, Linda Ruth, 2005: The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. Edinburgh University Press Comparison with the DVD. DVD grabs are on top; grabs from the new Arrow Blu-ray are on bottom.

|

|||||

|